Abstract

Background

Severe limb trauma is common in earthquake survivors. Overall medium term outcomes and patient-perceived outcomes are poorly documented.

Methods and Findings

The prospective study SuTra2 assessed the functional and socio-economic status of a cohort of patients undergoing surgery for limb injury resulting in amputation (A) or limb preservation (LP) one year and two years after the 2010 Haiti earthquake.

305 patients [A: n=199 (65%), LP: n=106 (35%)] were evaluated. Their characteristics were: 57% female; mean age 31 years; 74% of principal injuries involved the lower limb; 46% of patients had an additional severe injury; 60% had fractures, of which two-thirds were compound or associated with severe soft tissue damage; 15% of amputations were traumatic. At 2 years, 51% of patients were satisfied with the functional outcome (A: 52%, LP: 49%, ns). Comparison with the 1-year status indicates a worsening of the perceived functional status, significantly more pronounced in amputees, and an increase in pain complaints, mainly in amputees (62% and 80% of pain in overall population at 1- and 2-year respectively). Twenty eight percent (28%) of LP and 66% of A considered themselves as “cured”. 100% of LP and 79% of A would have chosen a conservative approach if an amputation was medically avoidable. Two years after the earthquake, 23·5 % of patients were still living in a tent, 30% were working, and 25·5% needed ongoing surgical management.

Conclusions

Only half the patients with severe limb injuries, whether managed with amputation or limb preservation, deemed their functional status satisfactory at 2 years. The patients’ perspective, clearly favors limb conservative management whenever possible. Prolonged care and rehabilitation are needed to optimize the outcome for earthquake survivors with limb injuries. Humanitarian respondents to catastrophes have professional and ethical obligations to provide optimal immediate care and ensure scrupulous attention to long-term management.

Keywords

Haiti earthquake, limb injury, two-year outcome, patients’ perspective, amputation, limb salvage

Funding Statement

This study was founded and supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR; URL: www.agence-nationale-recherche.fr/). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.Introduction

Many wounded earthquake survivors have limb injuries; resource constraints may compromise their optimal care. The decision to amputate is always difficult while the feasibility of limb preservation in the emergency response phase is uncertain. Functional disabilities due to limb injuries may jeopardize the return to work of injured individuals, who are likely to struggle economically and become a burden on their families and communities1. Finally, lower limb (LL) reconstruction has been shown more acceptable psychologically to patients with severe trauma compared with amputation even though the physical outcome for both management pathways was similar2. After the 12th January 2010 Haiti earthquake, about 1,200-1,500 amputations were performed for limb injuries3. Protracted rehabilitation of amputees as well as of patients undergoing limb reconstruction is unanimously considered crucial4,5,6,7.

Reports on victim management and outcome after mass catastrophe8,9 including those on the recent Haiti disaster 3,7,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 rarely extend more than six months after the tragedy. The non-governmental organization (NGO) Alliance for International Medical Action (ALIMA, France) in coordination with the Lille Economics Management (LEM, France) conducted a prospective observational cohort study 1 year and 2 years after the earthquake (SuTra2 Project). The aim was to document the medium-term outcome of individuals with severe limb injuries sustained during the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, treated with either limb amputation or limb surgical preservation with a special focus on the patient’s perspective. It was also planned to evaluate the impact of the surgical treatment on outcomes.

Methods

Patients and study design

Patients with limb injuries due to the earthquake, living in Port au Prince or its suburbs and who underwent limb surgery resulting in either limb amputation (A) or limb preservation (LP), were recruited by phone. They were contacted from database listings issued by: 1) The Clinique Lambert (Pétion-Ville, Haiti); two NGOs: 2) Handicap International (HI) and 3) Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), and 4) a local organization, l’Union des Jeunes Victimes du Séisme (UJVS) (Table 1). Limb surgery was defined as any surgical procedure on a limb that required general or regional anesthesia, whatever the delay from the initial injury. When a patient had injuries involving more than one limb, the principal injury according to the patient, was considered as the main injury. Associated severe injuries were named “additional” and could involve any part of the body.

Procedures

Patients fulfilling the above criteria, who agreed to participate in the study, were included in the 1-year assessment from January 21st to March 29th 2011, and in the 2-year assessment from January 23rd to March 29th 2012. Recruitment was stopped when everyone on the database listings had been contacted. Medical, quality of life (SF 36)21,22 and socio-economic data were collected through pre-established case report forms (CRF) in French. Demographics, history of the injury, surgical treatment, duration of hospitalization and physiotherapy, infection, pain (any pain and pain intensity through a visual analogue scale – VAS -), clinical examination of the injured limb (s), functional assessment (according to a 4-point scale; not satisfied, poorly satisfied, satisfied, very satisfied) and need for additional care were recorded. The socio-economic questionnaire explored the circumstances of the trauma, level of education, housing, family status and the theoretical patient preference between amputation and limb preservation (question addressed in 2011). To decrease the variability of the medical assessments, the number of examiners was restricted to three: a physician who examined amputees and nearly all the patients with limb reconstruction and two physiotherapists (one in 2011, one in 2012) trained in the study method by the physician, with a Creole translator when necessary. The physician reviewed all the patients’ charts and the medical CRFs. Three Haitian psychologists (2 in 2011, and 2 in 2012) administered the validated French SF36 and socio-economic questionnaires in patients over 15 years. When necessary, patients were referred to a specialised centre for surgical, physiotherapy or prosthesis advice, or for a psychological consultation. Patients or child’s parents (caretaker) provided written informed consent and received compensation for travel expenses. The study received Ethics Committee approval from the Haitian Ministry of Health in both 2011 and 2012.The protocol is available through the link https://www.alimaong.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/SuTra-protocol-research-EN-1.pdf. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT01779011).

Data handling and statistical analysis

In many cases, especially in amputees, the history reflected the patients’ description because no substantial patient record was available. Whenever possible, any information gathered from a patient chart, which was available for all the patients recruited via the Clinique Lambert (most LPs), was checked with the patient’s history. Radiographs at the time of the first surgical procedure were usually missing. Limb injuries were classified simply, indicating the presence of a fracture, closed or compound and/or presence of severe soft tissue damage with skin barrier impairment (SSTD). No severity scoring system could be applied retrospectively to the initial injuries. The main outcome criterion was an analysis of patients’ satisfaction with their functional status. Other outcome criteria were: satisfaction with the overall care, residual pain, need for additional care, resumption of previous physical activities, patient preference regarding their procedure, and employment status.

Descriptive analysis of quantitative and qualitative variables was performed for the overall population and according to the status A or LP, at 1-year and/or at 2-year, depending on the variable. As 76% of Haitians between 15- and 29-yr are single23, marital status was analyzed in the population over 29-yr. The main baseline characteristics (age, sex, proportion of A and LP, type and proportion of upper and lower limb injuries) of patients attending the 1- and 2-year visits were compared. Additional data analysis consisted of comparison of means (t-test, ANOVAs), and correlations. A subgroup analysis was conducted in 46 patients with lower limb injuries (A n= 23; LP: n=23), matched by age, sex, number of additional lesions and type of initial injury. SF36 scores were analysed according to Ware and Sherbourne21. Psychological (mean of the 4 psychological domains) and physical (mean of the 4 physical domains) subscales were also calculated (legend of Figure 2). Reliability, convergent and discriminating validities were measured and checked before applying the SF36 domains in the model. The SF 36 scores go from 0% to 100% (optimal)

Results

Baseline characteristics of the population

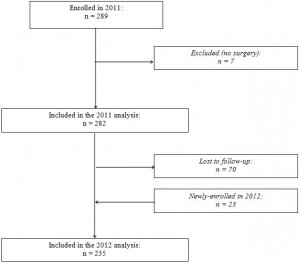

Patient sources are given in Figure 1 and Table 1. Overall 305 patients were included in the study, 282 in the functional and socio-economic analysis at 1-year, 235 at 2-year; 212 patients attended both 1 and 2-year visits and 70 patients (24%) were lost to follow-up between 2011 and 2012. The majority of patients with LP (96%) were enrolled from the Clinique Lambert database. Overall, patients had procedures in 65 different surgical centres. The baseline characteristics of patients attending the 1-year visit and the 2-year visit were similar.

Fig. 1: Diagram of the patients’ selection

Abbreviations: LP: Patients with limb preservation; yr: year

Amputees

L P

Total

All included (1 and / or 2-yr), n

199

106

305

188

94

282

152

83

235

Functional outcome population, n (%)

141 (71)

71 (67)

212 (70)

47 (24)

23 (22)

70 (23)

11 (5)

12 (11)

23 (7)

Patients source: n (%)

15 (8)

102 (96)

117 (39)

135 (68)

–

135 (44)

35 (18)

–

35 (11)

9 (4)

1 (1)

10 (3)

5 (2)

3 (3)

8 (3)

The main characteristics of the overall population, A and LP subgroups are given in Table 2. Amputees and patients with LP differed according to age, mode of extrication, location and type of principal limb injury, and number of injuries. In general, amputees were younger, and a higher proportion of amputees were below 15-yr. They also had predominantly lower limb (LL) injuries, and more severe injuries as evidenced by the greater frequency of compound fractures or severe associated soft-tissue damages (and traumatic amputation). Patients with LP had more closed fractures and more additional injuries.

Abbreviations: LP: limb preservation; n: number; sd: standard deviation; yr: year; hr: hour; LLI: Lower Limb Injury, ULI: Upper Limb Injury, SSTD: Severe Soft Tissue Damage; † p<0·05, ‡ p<0·01 comparison A vs LP. ∆ :Age in 2011; a: Population 1 year aged > 29 yr: overall n = 128, A: n = 78, LP: n = 50; b: Population 1 year, patients > 15 yr: n=238, A n=153; LP n= 85; 2 missing values °: Patients with at least one additional injury located on another limb or any other part of the body

Characteristics

Amputees

n = 199

LP

n = 106

Overall

n = 305

Female, n (%)

113 (57)

62 (58·5)

175 (57)

Age∆, yr, n (%)

33 (17)

9 (8)

42 (14)

164 (82)

94 (89)

258 (84)

2 (1)

3 (3)

5 (2)

29 (14)

35 (16)‡

31 (15)

Marital statusa, n (%)

47 (60)

30 (60)

77 (60)

Educationb, n (%)

50 (33)

37 (44)

87 (36)

Entrapmentb, n (%)

102 (67)

46 (54)

148 (62)

10 (10)

11 (24) †

21 (14)

– ≤ 6 hr

70 (68)

38 (82·5)

108 (73)

– > 6 ≤ 24 hr

16 (16)

3 (6·5)

19 (13)

– > 24 hr

16 (16)

5 (11)

21 (14)

Upper Limb Injury (ULI), n (%)

40 (20)

39 (37)

79 (26)

11 (5)

18 (17)

29 (9)

15 (8)

12 (11)

27 (9)

12 (6)

2 (2)

14 (5)

1 (0.5)

6 (6)

7 (2)

1 (0.5)

1 (1)

2 (1)

Lower Limb Injury (LLI), n (%)

159 (80)

67 (63)

226 (74)

80 (40)

21 (20)

101 (33)

62 (31)

14 (13)

76 (25)

14 (7)

24 (22)

38 (12)

2 (1)

4 (4)

6 (2)

1 (0·5)

4 (4)

5 (2)

Multiple Injuries°

86 (43)

55 (52)

141 (46)

35 (18)

25 (24)

60 (13)

1·4 (0·7)

1·65 (0·8) †

1·5 (0·7)

Main Injury, n (%)

104 (52)

81 (76) ‡

185 (60)

– Closed

10 (5)

50 (47) ‡

60 (20)

– Associated with SSTD

53 (26) ‡

10 (9)

63 (20)

– Compound

41 (21)

21 (20) ‡

62 (20)

40 (20) ‡

3 (3)

43 (14)

30 (15)

–

30 (10)

20 (10)

7 (7)

27 (9)

5 (2·5)

15 (14)

20 (7)

Management. The management of limb injuries (surgical procedures, hospital stays, physiotherapy) is given in Table 3. The delay to the first surgical procedure was shorter in amputees and only 3% of amputees had their first surgery performed beyond one month compared to 38% of patients with LP. Twenty nine percent of LP (29% ; 31/106) had limb injuries such as compound fractures or SSTD, which might have lead in this context to amputation. Conversely 15% of amputees (29 out of 199) had a previous attempt to preserve the limb. The rate of stump revision was 30% (61/199). Infections were commonest among amputees but chronic osteomyelitis was only observed as a complication of osteosynthesis. Hospital length of stay (cumulative) was significantly longer in amputees. Eighty nine percent (89%) of patients had access to physiotherapy, which lasted more than 3 months in 57% of them.

Abbreviations: LP: Limb preservation; n: number; sd: standard deviation; d: day; mo: month †: p<0·05, ‡: p<0·01 comparison A vs LP; •: Including traumatic amputation (n=30) ¶: Several surgical procedures possible under one anesthesia: all surgical procedures at first surgery: n=328 (A: n=205; LP: n=123) ¤: Delay to first surgery ≤ 30 days: n=253 (>30 days: A: n= 7, LP: n= 36) a: Population assessed in 2011, 2 missing data; for the population assessed in 2012 (n=235): mean number of surgical procedures: A: n= 2·1 (1·5), LP: n = 3·5 (2·1) ‡, overall : 2·6 (1·8)

Management

Amputation

n=199LP

n=106Overall

n=305

Delay to First Surgery¤, d, mean (sd)

6 (5·1)

11 (6·8) ‡

7 (5·9)

Type of First Surgery ¶, n

170

–

170

2

46

48

7

30

37

16

15

31

10

32

42

Surgical Proceduresa, n (%)

147 (74) ‡

49 (47)

196 (65)

51 (26)

56 (53) ‡

107 (35)

2·3 (1·9)

3·0 (1·9) ‡

2·5 (1·9)

Wounded limb infection:

157 (79) ‡

46 (43)

203 (67)

1

11

12

Duration of Hospital Stay, n (%)

87 (45)

52 (50)

139 (47)

60 (31)

36 (35)

96 (32)

46 (24)

15 (15)

61 (21)

63 (66) †

48 (51)

58 (61·5)

Physiotherapy, n (%)

179 (90)

93 (88)

272 (89)

– ≤ 3 mo

85 (49) †

28 (31)

113 (43)

– > 3 mo

88 (51)

63 (69) †

151 (57)

Functional status and outcome

Whole SuTra2population. Overall, 66% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with the functional results at 1-year. The rate of satisfaction decreased between 1 and 2 years, in particular among amputees: at 2-year, it was 51% in the overall population (Table 4). Persistent pain was recorded in 62 % and 80 % of patients at 1-and 2-year respectively. Pain was significantly more frequent in patients with LP than in amputees at one year but not at 2-year. Mean pain intensity was greater at 2 years in patients with LP [Maximum pain intensity -VAS-, mean (sd): overall: 5·4 (2·2); A: 4·3 (2·1); LP: 6·0 (2·3); intergroup p<0·01]. About half the patients, but significantly more amputees, considered they were “cured” both at 1- and 2-year. Conversely, all the patients treated with a reconstructive approach would choose this management again, while 79% of amputees would prefer reconstructive treatment if amputation were not medically unavoidable. The majority of patients (85·5%) declared they were satisfied with the care they received. Two years after the earthquake, 30% of patients were working, significantly more LP than A; 23·5% were still living in a tent and 46% declared to have some difficulties to access to food; 25·5% would require additional surgical management, mainly stump revision or osteosynthesis material removal.

Abbreviations: LP: Patients with limb preservation; n: number; yr: year

a : Population 1-year: Overall n=282, A n=188, LP n=94 b : Population 2-year: Overall n=235 , A n=152 , LP n=83c:Population 1-year (> 15 yr) : Overall n=243, A n= 157, LP n= 86 ; c1 19 missing values; c2 among 199 not working, 10 missing values; c3 5 missing values; c4 7 missing values d: Population 2-year (> 15 yr): Overall n=205, A n=141, LP n=75; d1 2 missing values; d2 1 missing value ‡: p<0·01; *: Comparison 2011 vs 2012 (intragroup); °: Comparison A vs LP (intergroup)

Amputation

L P

Overall

Functional status: Satisfied or very satisfied, n (%)

130 (69)

55 (58·5)

185 (66)

79 (52)*‡

41 (49)

120 (51)*‡

“Cured”, n (%)

115 (61)

29 (31)°‡

144 (51)

101 (66)

23 (28)°‡

124 (53)

Resuming previous physical activities at 2-yrb

51 (34·5)

13 (16)

64 (27)

Persistent pain, n (%)

106 (56)

70 (74·5)°‡

176 (62)

116 (76)*‡

71 (85·5)

187 (80)*‡

Satisfaction with overall care, n (%)

126 (83)

75 (90)

201 (85·5)

Need for referring at 2-yrb

57 (37·5)

50 (60) ‡

107 (45·5)

28 (18)

32 (38·5)

60 (25·5)

6 (4)

14 (17)

20 (8·5)

23 (15)

4 (4)

27 (11)

Need for psychological support at 2-yrb, n (%)

19 (12·5)

12 (14·5)

31 (13)

Patients’ theoretical preference for LPc1, n (%)

111 (79)

83 (100) ‡

194 (87)

Working status, n (%)

– Work lost since the earthquakec2

76 (57)

26 (47)

102 (54)

– Workingc3

17 (11)

22 (26) °‡

39 (16)

33 (26) *‡

27 (37)

60 (30) *‡

Housing in a tent, n (%)

64 (42)

36 (42)

100 (42)

34 (26) *‡

14 (19) *‡

48 (23·5) *‡

Not enough food, n (%)

14 (9)

7 (8)

21 (9)

96 (64)

44 (52)

140 (59)

64 (49) *‡

31 (42)

95 (46) *‡

Amputees and prosthesis. At 1- and 2-year, 92 % and 96% of the LL amputees, 11% and 28% of the upper-limb (UL) amputees respectively had a prosthesis, which was used a mean of 9 hours and 11 hours a-day respectively. The first prosthesis was delivered within a mean of 136 days. The proportion of amputees satisfied with their prosthesis at 1- and 2-year was 66% and 75%, respectively. Disabling phantom limb pain was infrequent (18 out of 141: 13%).

Subpopulation of amputees and patients with limb preservation, matched for the main baseline characteristics. n those 46 patients (A: n = 23, LP: n=23) with lower limb injury, matched for age, sex, type of injury and number additional lesions, trends similar to those observed in the global population were noticed. The worsening of the perceived functional status between 2011 and 2012 was even more pronounced in amputees (satisfied/very satisfied: 1-yr: 87%; 2-yr: 22%) compared to patients with LP (satisfied/very satisfied: 1-yr: 65%; 2-yr 14: 61%) .

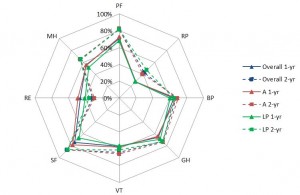

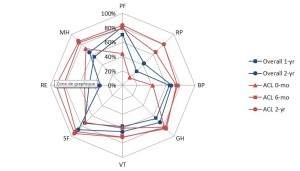

Quality of life

The variations in SF36 scores between 2011 and 2012 are shown in Figure 2, with a reference to a group of Swedish subjects with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction24(Figure 3). At 1-year, the health-related quality of life was impacted in nearly all SF 36 domains (Figure 2). Between 2011 and 2012, meaningful positive changes were observed in all affected domains except for body pain, which was stable and for emotional role, which worsened, mostly in amputees. Mean (sd) physical and mental SF 36 subscales significantly increased from 57% (19) to 66·5% (11) and from 58% (20) to 62% (10) respectively in the overall population, with a similar magnitude across treatment groups for the physical subscale. The mental subscale improved in LP [(from 55% (20) to 62% (10)], but not in amputees [from 60% (20) to 62% (10)]. At 2-yr emotional and physical roles were more negatively impacted in this Haitian series than in the Swedish subjects with ACL reconstruction (Figure 3.), underlining the severity of both the initial wounds and their late consequences in the present cohort.

A: amputees; LP: Limb preservation; yr: year; mo: month; PF: Physical Functioning, RP: Role Physical, BP: Bodily Pain, GH: General Health, VT: Vitality, SF: Social Functioning, RE: Emotional Role, MH: Mental Health. Definitions:Physical subscale = mean of PF, RP, BP and GH; Mental subscale = mean of VT, SF, RE, MH; SF 36 score is improving from inner (0%) to outer (100%). At 1-year: overall n = 254, A: n= 161, LP: n= 93; At 2-year: overall: n = 204, A: n= 127, LP: n=77

Fig. 2: SF 36 scores at 1-year and 2-year (dotted lines) in the overall population, A and LP

SF 36 score is improving from inner (0%) to outer (100%). * ACL: Swedish subjects,24: n = 62; mean age: 26 yr, male 80% (ref. 24)

Fig. 3: SF 36 scores at 1-year and 2-year in the overall population, with reference to Swedish subjects with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction at 6-month and 2-year*.

Discussion

Survivors of major trauma with orthopedic injuries especially lower limb injuries, usually have poor functional outcomes and quality of life25, particularly after a mass disaster in a developing country. The SuTra2study indicates that 2 years after the Haiti earthquake, only half the patients with limb injury, whether amputated or treated by conservative surgery, are satisfied with the functional results. The comparison of the outcome between 1 and 2 years shows a worsening of the perceived functional status while in parallel, the socio-economic status improved moderately. However at 2 years,only 30% of those victims with a job prior to the earthquake are working, 46% find access to food more or less problematic, and 23·5% are still living in a tent, a situation In Haiti known to be associated with negative outcomes for income, employment, and food access16.

As expected10 , 26 patients treated with conservative surgery were more frequently operated on than amputees. However, amputation was far from a straightforward procedure. The rate of stump revision was 30%, a figure in the range of those observed by others4 after the Haiti earthquake, far exceeding the 5.4% rate reported in the best, first world conditions27 . Furthermore, compared with patients with LP, amputees had a greater length of hospital stay. As observed in conventional medical settings2, amputation yields worse psychological outcomes, according to the SF36 scoring system, when compared to limb reconstruction. Compared to transtibial28 and transfemoral29 amputees retrospectively analyzed more than 28 years after the initial injury during the Vietnam War, quality of life impairments at 2-years in amputees after the Haiti earthquake were similarly with regards to the “role physical” (RP), but worse for the “role emotional” (RE) dimensions, indicating notable impairments due to physical limitations and their psychological consequences. However, contrary to Vietnam War amputees, the perceived health status of SuTra amputees (physical functioning – PF- ) was similar to controls. Although at 1 year amputees had better perceived functional outcomes than LP, and more amputees than patients with LP considered they were “cured” at 2 years, fewer amputees were at work at 2 years. Finally, most amputees (79%) would have preferred not to undergo amputation if it could have been avoided.

The SuTra2study population is representative of the population with severe limb injuries due to the Haiti earthquake reported by others4,7 . The study has included about 13% of all the amputees after the earthquake. The recruitment of amputees through organizations which mainly provide lower limb prostheses explains the lower rate of upper limb involvement (26%) in the SuTra2population, in comparison to the 36% rate reported by others4 , but a 37% ratio between UL and LL limb involvement was observed in the SuTra2 patients with limb preservation. Amputations were performed earlier than conservative surgery (mean: day 6 post-earthquake). Inadequate numbers of specialized orthopaedic and plastic surgeons, not present yet in Haiti4 , and / or a lack of material resources, as well as the severity of the injuries may explain this early peak in amputation. Retrospective interviews among orthopedic surgeons who volunteered in Haiti within 30 days of the earthquake19 , suggested that inappropriate care may had occurred after the disaster. A considerable number of patients may have received primary amputation for complex injuries of limbs, which may have been salvageable3 . Indeed, the lowest rate of amputation has been reported in teams with a combination of orthopedic and plastic surgeons4 , 10. In the present series, a sizable number (29%) of victims undergoing conservative surgery had injuries which might have lead to amputation. In poor economies with minimal infrastructure and limited access to quality prostheses, the human and economic burden of limb loss can only be worse than in wealthy countries10.

The limitations of the study must be acknowledged. First, the lack of medical records and the heterogeneity of both the wounds and their initial treatment hampered analysis of outcomes in relation with the initial injuries and their management. This is a common drawback in reports on Haiti earthquake4 . Second, the mode of recruitment explains the higher proportions of amputees (65% of the patients), and of amputees younger than 15 years, compared to patients with LP, observed in the study. Finally, the 24% dropout rate between 2011 and 2012 should be seen in perspective, with poor living conditions and low socio-economic status for most patients. In the LEAP cohort conducted in a wealthy country, and followed for 7 years 26,30, the dropout rate at 2 years reached almost 20%. The wide distribution of mobile phones in Haiti, the word of mouth recruitment, and the reimbursement of the transport costs for attending the visits may have enhanced both the recruitment and the relatively high retention in the study in spite of the surrounding environment.

After a major earthquake, both the organization of emergency medical rescue to ensure optimal initial care9, and the long-term management of limb-injured victims are crucial for a favourable outcome. Despite inherent limitations, this study gives valuable information on the outcome of patients with severe limb injury after a mass catastrophe that can help prepare for future emergencies. First, notwithstanding a favourable outcome for amputees at one year, perceived functional status deteriorates with time, more rapidly than in patients with reconstructive management. Second, patients prefer limb preservation whenever possible. Third a sizeable proportion of amputees might have benefited from limb conserving treatment; in agreement with others9,10, wherever possible resources should be directed at limb salvage because of these potential long term benefits. Finally long term care and rehabilitation are mandatory for improving the outcome whatever the initial surgery performed, amputation or limb reconstruction, because the initial surgical procedure may have been sub-optimal, and the socio-economic context in developing countries is challenging. In mass disasters, postponing definitive surgery until adequate human and technical resources are available, or a transfer to tertiary referral centre is possible, may sometimes be the wisest decision18,31.Particular attention should be paid to clinical records, which should be handed to the patient4 . Guidelines for the overall management of limb injuries in mass casualties, as those established by Knowlton and colleagues31 for amputation, should be promoted. There is a professional and ethical obligation on those who provide humanitarian relief to achieve the best immediate outcomes possible in the circumstances, and also to recognize the long-term care, which will be needed to optimize outcomes for their patients.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the literature search. Thierry Allafort-Duverger (TAD), Nikki Blackwell (NB), Stéphane Callens (SC), Marie C. Delauche (MCD), and Nezha Khallaf (NK) conceived the study concept and design. MCD in collaboration with SuTra2 team members quoted in the acknowledgments acquired the data. Hervé Le Perff (HLP) in collaboration with SuTra2team members did the data processing. SC, NK, HLP, Joel Muller (JM), analyzed the data. All authors took part in their interpretation. NB, SC, MCD, HLP, NK, JM drafted the report, and all authors provided critical revisions and approved the final report. TAD NK, SC obtained funding from the he French Agence Nationale de Recherche.

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests associated with any of the authors

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Margaret Degand, MD (plastic surgeon), Dr Harvel Durverseau, MD (orthopedic surgeon) from the Clinique Lambert (Pétion-Ville, Haiti) for their dedicated and tremendous involvement in the care of the patients. We thank all the teams of surgeons, anesthetists, nurses, physiotherapists and orderlies who worked at La Clinique Lambert with ALIMA, for their collaboration. We are specifically grateful to the physiotherapists Jean Lundi for the contribution in the 1-year assessment and Agathe Verrier for the 2-year one, to the three Haitian psychologists, to the nurse Aurélie Kemplaire for her remarkable coordination of patients’ care, to Isabelle Leger for her exceptional efficiency in the recruitment of patients, to Davidson Pierre for the data entry and Creole translation, to Isabelle Leger and Garry Lindor for the support of patients and Creole translation, and to Barbara Baille for the organization of the study in 2011 and data entry. We also thank Handicap International, Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, and l’Union des Jeunes Victimes du Séisme for their collaboration.References

- Hettiaratchy SP, Stiles PJ (1996) Rehabilitation of lower limb traumatic amputees: The Sandy Gall Afghanistan Appeal’s experience. Injury 27: 499-501

- Akula M, Gella S, Shaw C J, Mohsen AM, McShane P (2011) A meta-analysis of amputation versus limb salvage in mangled lower limb injuries - The patient perspective. Injury 42: 1194-1197.

- O’Connell C, Shivji A, Calvot T () Preliminary findings about persons with injuries. Haiti Earthquake 12 January 2010, Handicap International Report. 2010. Available : https://reliefweb.int/node/343807. Accessed 18 February 2011.

- Redmond AD, Mardel S, Taithe B, Gosney J., Duffine A. et al. (2011) A qualitative and quantitative study of the surgical and rehabilitation response to the earthquake in Haiti, January 2010. Prehosp Disaster Med 26; 449-456.

- Tataryn M., Blanchet K (2012) Evaluation of post-earthquake physical rehabilitation response in Haiti, 2010 – a systems analysis. International Centre for Evidence on Disability (ICED), London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), January, 22 p. Available : https://disabilitycentre.lshtm.ac.uk, Accessed 10 October 2012.

- Landry MD, O’Connell C, Tardif G, Burns A (2010) Post-earthquake Haiti : The critical role for rehabilitation services following a humanitarian crisis. Disabil Rehabil 32: 1616–1618.

- De Ville de Goyet C, Pablo Sarmiento J, Grünewald F (2011) Health response to the earthquake in Haiti January : Lessons to be learned for the next massive sudden-onset disaster. Pan American Health Organization ; Washington DC, p180 https://www.paho.org/disaster. Accessed 10 October 2012.

- Bartels SA, Van Rooyen MJ (2012) Medical complications associated with earthquakes. Lancet 379: 748–757.

- Zhang L, Liu X, Li Y, Liu Y, Liu Z et al. (2012) Emergency medical rescue efforts after a major earthquake: lessons from the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Lancet 379: 853-861.

- Clover AJP, Rannan-Eliya S, Saeed W, Buxton R, Majumder S, et al. (2011) Experience of an orthoplastic limb salvage team after the Haiti earthquake: Analysis of caseload and early outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg 127: 2373- 2380.

- Jaffer AK, Campo RE, Gaski G, Reyes M, Gebhard R et al. (2010) An academic center’s delivery of care after the haitian earthquake. Ann Intern Med 153: 262-265.

- Bar-On E, Lebel E, Kreiss Y, Merin O, Benedict S, et al. (2011) Orthopaedic management in a mega mass casualty situation: the Israel Defence Forces Field Hospital in Haiti following the January 2010 earthquake. Injury 42: 1053–1059.

- Peranteau, WH, Havens JM, Harrington S, Gates J. (2010) Re-establishing surgical care at Port-au-Prince general hospital, Haiti. J Am Coll Surg 211: 126-130.

- Bayard D. Haiti earthquake relief, phase two - Long-term needs and local resources. (2010 ) N Engl J Med 362: 1858-1861.

- Ginzburg E, O’Neill WW, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, de Marchena E, Pust D, et al. (2010) Rapid medical relief: Project Medishare and the Haitian earthquake. N Engl J Med 362: e31.

- Kirsch TD, Leidman E, Weiss W, Doocy S. (2012) The impact of the earthquake and humanitarian assistance on household economies and livelihoods of earthquake-affected populations in Haiti. Am J Disaster Med 7: 785-794.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL, Menon AS, Brown IP, Kuah S, et al. (2010) Civil-military collaboration in the initial medical response to the earthquake in Haiti. N Engl J Med 362: e32.

- Missair A, Gebhard R, Pierre E, Lubarsky D, Frohock J, et al. (2010) Surgery under extreme conditions in the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake: the importance of regional anesthesia. Prehosp Disaster Med ; 25: 487-493.

- Sonshine DB, Caldwell AC, Gosselin RA, Born CT, Coughlin RR. (2012) Critically assessing the Haiti earthquake response and the barriers to quality orthopaedic care. Clin Orthop 470: 2895-2904.

- Cerdá M, Paczkowski M, Galea S, Nemethy K, Péan C, et al. (2012) Psychopathology in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake: a population-based study of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Depress Anxiety Nov 1. doi: 10.1002/da.22007

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 6: 473-483.

- Leplège A, Ecosse E, Pouchot J, Coste J, Perneger T. (2001) Le questionnaire MOS SF-36: Manuel de l’utilisateur et guide d’interprétation des scores, Editions ESTEM, Paris, 155 p.

- Institut Haïtien de statistique et d’informatique, Ministère de l’Economie et des Finances. (2003) Enquête sur les conditions de vie en Haïti (ECVH2001): Population, ménages et familles. 1: 2, Available: https://www.ihsi.ht/pdf/ecvh/ECVHVolumeI/Population.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2012.

- Busija L, Osborne RH, Nilsdotter A, Buchbinder R, Roos EM. (2008) Magnitude and meaningfulness of change in SF-36 scores in four types of orthopedic surgery. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 6:55. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-55

- Balogh ZJ, Reumann MK, Gruen RL, Mayer-Kuckuk P, Schuetz MA, et al. (2012) Advances and future directions for management of trauma patients with musculoskeletal injuries. Lancet 380: 1109-1119.

- Bosse MJ, Mackenzie EJ, Kellam JF, Burgess AR, Webb LX, et al. (2002) An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation of leg-threatening injuries, N Engl J Med 347: 1924-1931.

- Harris AM, Althausen PL, Kellam J, Bosse MJ, Castillo R (2009) Complications following limb-threatening lower extremity trauma. J Orthop Trauma 23:1-6.

- Dougherty PJ. (2001) Transtibial amputees from the Vietnam War. Twenty-eight-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83:383-389.

- Dougherty PJ. (2003) Long-term follow-up of unilateral transfemoral amputees from the Vietnam War. J Trauma 54:718–723.

- MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Pollak AN, Webb LX, Swiontkowski MF, et al. (2005) Long-term persistence of disability following severe lower-limb trauma: Results of a seven-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:1801-1809.

- Knowlton LM, Gosney JE, Chackungal S, Altschuler E, Black L, et al. (2011) Consensus statements regarding the multidisciplinary care of limb amputation patients in disasters or humanitarian emergencies: Report of the 2011 Humanitarian Action Summit Surgical Working Group on amputations following disasters or conflict, Prehosp Disaster Med; 26: 438-448; doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12000076

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.