Abstract

Background: Children are a special population, particularly susceptible to injury. Registries for various injury types in the pediatric population are important, not only for epidemiological purposes but also for their implications on intervention programs. Although injury registries already exist, there is no uniform injury classification system for traumatic mass casualty events such as earthquakes.

Objective: To systematically review peer-reviewed literature on the patterns of earthquake-related injuries in the pediatric population.

Methods: On May 14, 2012, the authors performed a systematic review of literature from 1950 to 2012 indexed in Pubmed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. Articles written in English, providing a quantitative description of pediatric injuries were included. Articles focusing on other types of disasters, geological, surgical, conceptual, psychological, indirect injuries, injury complications such as wound infections and acute kidney injury, case reports, reviews, and non-English articles were excluded.

Results: A total of 2037 articles were retrieved, of which only 10 contained quantitative earthquake-related pediatric injury data. All studies were retrospective, had different age categorization, and reported injuries heterogeneously. Only 2 studies reported patterns of injury for all pediatric patients, including patients admitted and discharged. Seven articles described injuries by anatomic location, 5 articles described injuries by type, and 2 articles described injuries using both systems.

Conclusions: Differences in age categorization of pediatric patients, and in the injury classification system make quantifying the burden of earthquake-related injuries in the pediatric population difficult. A uniform age categorization and injury classification system are paramount for drawing broader conclusions, enhancing disaster preparation for future disasters, and decreasing morbidity and mortality.

Funding Statement

There was no external funding provided. The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.Introduction

Traumatic injuries are the leading cause of death among persons 10-19 years of age worldwide1, and among persons 1-44 years of age in the United States.2 Injury registries are necessary, not only for epidemiological purposes but also for their implications on designing intervention programs and disaster preparedness. Several injury registries have been developed in the past, such as the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS)2 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB)3. However there is currently no uniform international database for injuries sustained in natural disasters such as earthquakes, neither in adult nor pediatric populations. In order to provide robust disaster preparedness and an optimized response, this information must be available in an organized repository. The objective of this article is to systematically review the peer-reviewed literature regarding the pattern of earthquake-related injuries in the pediatric population, and to use these findings to provide recommendations for improving reporting and classification of pediatric injuries in disasters.

Methods

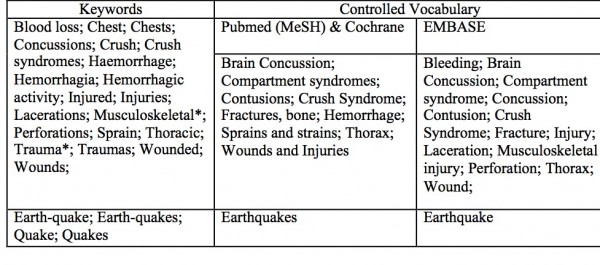

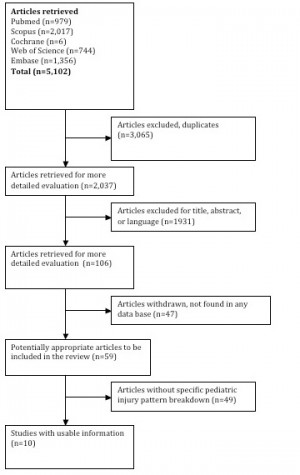

Study Design: The authors performed a systematic review by searching literature from 1950 to 2012 indexed in Pubmed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. All searches were performed on May 14, 2012. A comprehensive search strategy was developed and translated into each databases’ syntax. The search was limited to medical related subject areas in Scopus and Web of Science to limit off-topic literature retrieved due to the wider scope of those databases. The search included an earthquake concept and a trauma concept. Terms were searched as controlled vocabulary in applicable databases (Pubmed, Embase, Cochrane) and as keywords in all databases (Appendix 1). All terms were searched as exact phrases in all databases. The search method algorithm is detailed in Figure 1.

Results from the five databases were combined and duplicates were excluded, yielding a total of 2,037 articles. Title screening was performed to identify articles that were unrelated to natural disasters or human populations. Each title was screened by three reviewers and was retained if any of the reviewers established that inclusion criteria were met. During review of article titles, consensus was met when two out of three agreed on the relevance of the titles to advance in the systematic review. Inclusion Criteria: Articles written in English providing a quantitative description of the types of direct physical injuries sustained immediately in the aftermath of earthquakes, and specifying the ages of injured patients. Exclusion Criteria: Articles about other types of disasters, geological, surgical, and conceptual articles, articles describing psychological impact, indirect injuries, injury complications such as wound infections and acute kidney injury, case reports, reviews, and/or articles in languages other than English. A total of 106 articles underwent full review by all three authors; all three authors agreed on the final 10 articles included in this review.

Results

A total of 2,037 articles were retrieved, of which only 10 (0.49%) contained quantitative data on earthquake-related pediatric injuries and could be used in the final analysis.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 These articles and their characteristics are outlined in Table 1. All 10 studies were retrospective. Studies had different pediatric age group upper limits ranging from 14 to 18 years. The average number of pediatric patients in the 10 studies was 124 (range 33-254). Each study reported pediatric injuries using heterogeneous categories and classifications; using injury type (e.g. fracture) or location (e.g. head, upper limb, trunk), or a combination of both. Only five studies focused solely on pediatric patients, two of which reported patterns of injury for all pediatric patients, whether admitted to the hospital or discharged after initial treatment. Only one article described the injuries by anatomic location, and one described injuries by type; the remaining eight articles described injuries using a variety of combinations of both systems.

Author

Title

Year Article Pub- lished

Site of Earth- quake

Year of Earth- quake

Age Group of Study Popu- lation

Number of Injured Pediatric Patients Studied

Additional Study Population Characteristics

Age of Pediatric Popu- lation

Gueri M

The Popayan earthquake: A preliminary report on its effect on health

1984

Columbia

1983

all

41

Analysis of admitted patients only

<15 yrs

Reyes Ortiz M

Brief description of the effects on health of the earthquake of 3rd March 1985 — Chile

1986

Chile

1985

all

254

<15 yrs

Sanchez-Carillo CI

Morbidity Following Mexico City’s 1985 Earthquakes

1989

Mexico

1985

all

128

<15 yrs

Iskit SH

Analysis of 33 Pediatric Trauma Victims in the 1999 Marmara, Turkey Earthquake

2001

Turkey

1999

pediatric

33

Analysis of pts transferred to referral hospital

14 days- 16 yrs

Sarisozen B

Extremity Injuries in Children resulting from the 1999 Marmara earthquake: an epidemiologic study

2003

Marmara

1999

all

51

Admitted patients only

<16 yrs

Sabzehchian M

Pediatric Trauma at Tertiary-Level Hospitals in the Aftermath of the Bam, Iran Earthquake

2006

Iran

2003

pediatric

119

Analysis of pts admitted to 3 referral hospitals

<16 yrs

Bai X

Retrospective analysis: the earthquake-injured patients in Barakott of Pakistan

2009

Pakistan

2005

all

151

9 mos- 16 yrs

Xiang B

Triage of pediatric injuries after the 2008 Wen-Chuan earthquake in China

2009

China

2008

pediatric

119

Admitted patients only

pre- school, school

Farfel A

Haiti earthquake 2010: a field hospital pediatric perspective

2011

Haiti

2010

pediatric

155

0-18 yrs

Zhao J

Sichaun Earthquake and Emergency relief care for children

2011

Sichuan

2008

pediatric

192

<18 yrs

Fractures were the most commonly identified type of injury (four of the seven articles) with reported percentages ranging from 18.1% to 55.2% (pooled percentage 30.6%).9,10,12,13 Soft tissue injuries were the second most common type of injury, ranging from 17.6% to 70.2%.4,5,8 Pooled percentages could not be calculated for this type of injury because universal nomenclature was not employed when reporting. Crush injuries were frequently cited, ranging from 6.3% to 18.7% (pooled percentage 20.4%). Special mention was made to the secondary consequences of renal failure and the need for dialysis. Table 2 illustrates the specific classification of Injury by article, where possible, injury percentages are presented alongside the raw data.

Many of the articles that reported injury by location focused only on orthopedic injuries, with fracture of extremities accounting for 17.1% to 60.8% (pooled percentage 36.8%).4,8,9,11,12,13 A single article identified the head as the most common location for trauma.6 The percentage of head injuries ranged from 3.2% to 61% (pooled percentage 18.4%). The incidence of reported spinal trauma ranged between 4.9% and 31.1% (pooled percentage 6.5%).7,9,11

Author

Year Article Published

Number of Injured Pediatric Patients Studied

Injuries Classified by Type

#

% of Injured Patients

Injuries Classified by Location

#

% of Injured Patients

Gueri M

1984

41

multiple trauma

5

12.2%

head injury

25

61.0%

fracture

10

24.4%

lower limb

4

9.8%

spinal column

2

4.9%

upper limb

3

7.3%

other

1

2.4%

traumatism (not specified)

1

2.4%

intraabdominal/ thoracic

1

2.4%

Reyes Ortiz M

1986

254

fracture

46

18.1%

skull bones and face

1

0.4%

neck and trunk

5

2.0%

upper extremity

12

4.7%

lower extremity

28

11.0%

dislocation

0

0.0%

intracranial injury without fracture

27

10.6%

sprains and tears

7

2.8%

internal injury to chest/abdomen/pelvis

2

0.8%

wound

104

40.9%

head, neck, trunk

55

21.7%

upper extremity

14

5.5%

lower extremity

35

13.8%

superficial injury

0

0.0%

contusion without alteration of skin

46

18.1%

bruises

4

1.6%

injury to nerves and spinal column

0

0.0%

complication of unspecified injury

2

0.8%

other

14

5.5%

Sanchez-Carillo CI

1989

128

multiple traumas

21

16.4%

simple fractures

19

14.8%

compound fractures

2

1.6%

simple contusions

37

28.9%

crushing

0

0.0%

wounds with contusions

18

14.1%

other

13

10.2%

Iskit SH

2001

33

crush injuries

15

CNS

8

24.2%

soft tissue

19

vertebral column

2

6.1%

peripheral nerve palsy

3

thoracic compression

1

3.0%

retroperitoneal hematoma

2

6.1%

fracture

8

24.2%

extremity

6

18.2%

pelvis

2

6.1%

Sarisozen B

2003

51

extremity and spine

31

60.8%

chest

1

2.0%

abdomen

3

5.9%

head

3

5.9%

other

5

9.8%

unknown

8

15.7%

Sabzehchian M

2006

119

joint injury

60

50.4%

upper/lower limb

10/50

8.4%/42.0%

laceration

61

51.3%

upper/lower limb

5/56

4.2%/47.1%

fracture

63

52.9%

upper/lower limb

11/52

9.2%/43.7%

ecchymosis

40

33.6%

upper/lower limb

9/31

7.6%/26.1%

hematoma

21

17.6%

upper/lower limb

2/19

1.7%/16.0%

deep wound

23

19.3%

upper/lower limb

1/22

1.7%/18.5%

vascular

13

10.9%

upper/lower limb

0/13

0.0%/10.9%

chest and abdomen

17

14.3%

head and spinal cord

37

31.1%

Bai X

2009

151

open soft tissue injury

106

70.2%

upper extremity wound

27

17.9%

open fracture

6

4.0%

lower extremity wound

37

24.5%

closed fracture

20

13.2%

head wound

34

22.5%

pain only

19

12.6%

trunk wound

2

1.3%

multple sites wound

12

7.9%

Xiang B

2009

119

fractures

104

upper limb

26

lower limb

60

pelvis

12

skull

2

thoracic spine

4

nerve injury

7

limb compartment syndrome

17

dislocation

2

liver fracture

5

soft tissue injury

4

hemopneumo- thorax

4

Farfel A

2011

155

fractures

48

31.0%

head injuries

5

3.2%

open wounds

52

33.5%

crush injuries

29

18.7%

superficial injuries

29

18.7%

contusion

8

5.2%

dislocations

5

3.2%

other

6

3.9%

Zhao J

2011

192

simple, open

127

66.1%

head

23

12.0%

simple, closed

41

21.4%

face and neck

6

3.1%

combined open and closed

35

18.2%

chest

18

9.4%

crush injury

12

6.3%

abdomen

6

3.1%

fracture

106

55.2%

pelvis

13

6.8%

soft tissue

73

38.0%

spine

17

8.9%

limb

106

55.2%

body surface

67

34.9%

Discussion

The pediatric patient is likely to present with a unique array of injury patterns, secondary to differences in physiology and anatomy. By better understanding the specific injuries this population may face, healthcare providers may more adequately prepare for the needs of this vulnerable population in post-disaster settings. Therefore, trauma registries in any population, especially vulnerable subpopulations such pediatrics, are important to capture data for research, measure trauma system outcomes, and support quality improvement through assessment of the appropriateness and effectiveness of the trauma system.14 A trauma registry can be defined as “a disease specific collection composed of a file of uniform data elements that describe the injury event, demographics, prehospital information, diagnosis, care, outcomes, and costs of treatment for injured patients”.15 In most cases it is computerized, permitting ease of analysis and tracking of quality improvement data elements. It is this ease of analysis and ability to track specific data (such as complications or process-of-care measures), as well as ability to adjust for severity of injury, that distinguish trauma registries from general medical records systems.16

Injury Patterns in Pediatric Survivors of Earthquake

Overall our systematic review of injury patterns in the pediatric population demonstrated a high incidence of fracture-related injuries (30.6%) and wounds. Our findings that extremities were the most common site of injury (36.8%) was also reported by Bartels, et al.17 Head injury and spinal injury were reported in 18.4%6 and 6.5%11 of patients, respectively. It is important to note that head injury reporting varied significantly depending on the author’s classification (with or without fracture, and with or without intracranial hemorrhage).

Our review also revealed that crush injuries are consistently reported (in 4 out of 10 articles). Crush injury and crush syndrome are common earthquake injury patterns. Crush injury is defined as compression of extremities and body parts that causes muscle swelling or neurologic disturbances in the affected parts of the body. Typically affected body parts include lower extremities (74%) and upper extremities (10%).18 These two locations were the most commonly reported injury sites in this review: 34.2% and 12.3%, respectively.19

Challenges in the Evaluation of Pediatric Injury Patterns

Our systematic review on earthquake-related pediatric injuries highlights major challenges regarding pediatric injury reporting in disaster settings. These challenges can be regarded as both limitations and urgent needs for consensus and future prospective research. The first challenge is related to the upper age limit of a “pediatric” patient in reporting injuries, as the definition of what constitutes a “child” varied significantly among these studies between 14 and 18 years of age. Consequently, that finding posed a major difficulty when compiling data, even for comparable injuries. The American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank uses < age 20 years as their upper limit, however the facilities from which they receive data use anywhere from age 11 years to age 21 years, as the upper limit.20 The ACS also further classifies pediatric trauma information into the following age groups: < 1 year, 1-4 years, 5-9 years, 10-14, 14-19,20 which none of the ten articles in our systematic review reported.

The second challenge relates to the substantial heterogeneity in classifying pediatric injuries. Our final 10 articles with related earthquake-related pediatric injuries had widely different methods for how data was collected, categorized and reported. As a result, the information was very difficult to interpret, which makes injury-specific disaster planning difficult. One way to potentially circumvent this challenge would be to adopt international classification standards such as International Classification of Disease (ICD)21 codes, the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of External Causes of Injuries (ICECI)24 as well as Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS)22 , and Body Region (Head, Lower Extremity, Thorax, Abdomen, Upper Extremity, Spine, External/Other, Face, Neck) notation used by the National Trauma Data Bank in the United States3 . International agreement on any injury classification system is an involved process, but could be undertaken and implemented by credible entities such as the WHO.

The third challenge is the technical reporting of numerical results. In five of the ten studies, it was difficult to ascertain the denominator to calculate percentages of injuries, when only raw injury counts were provided.5,8,10,11,12 For example, in the article by Xiang et al., where 119 injured pediatric patients were studied, the authors reported 17 limb compartment syndromes and 60 lower limb injuries.12 It was unclear from their data if these injuries are reported on different patients or if single patients accounted for more than one injury. In other words, we could not simply ascertain if a patient with bilateral lower limb injuries was counted once or twice. These numerical reporting discrepancies among various studies can have a huge epidemiologic impact.

The fourth challenge is the striking paucity of reporting pediatric-specific data in traumatic injuries. It is postulated that pediatric injuries are more likely to be underreported, due to the fact that children have a higher mortality rate, may have survived with fewer injuries or were incapable of reaching the hospital due to familial constraints.5 From the 59 articles identified with quantitative data on patterns of injuries in earthquakes, only ten contained pediatric quantitative data, of which only five had a main objective of reporting pediatric injuries. This challenge is encountered worldwide, even for individual injuries. For example, in the U.S. the National Pediatric Trauma Registry (NPTR), a multi-state pediatric-specific trauma registry was discontinued in 2002 due to the lack of funding.14 The Trauma Data Bank remains the largest repository of trauma records in the United States; however, it has not focused specifically on pediatric data collection.

The fifth challenge is the feasibility of comprehensive data registry systems in the aftermath of large scale disasters. In such chaotic situations, it can be very difficult to collect sufficient patient information.

Interesting areas of future research, beyond the scope of this paper, include considering the scale of hazard, e.g. the magnitude of earthquakes and seismic intensity in the sites, and vulnerability, e.g. basic infrastructure, health services, and building codes in the sites. These factors can influence the type and severity of the injuries. In addition, a comparison should be made between the characteristics of the earthquake-related injuries among the paediatric population and the earthquake-related injuries among the general population and with those of the paediatric population in usual settings.

Conclusions

Differences in age group definitions of pediatric patients, and in the injury classification system contribute to difficulty in quantifying the burden of earthquake-related injuries in the pediatric population. Uniform age limits and injury classification systems are paramount for drawing broader conclusions, enhancing disaster preparation for future earthquake disasters and decreasing morbidity and mortality. Some of these conclusions may be applicable to other types of disasters causing pediatric injuries. Further research in the area of pediatric trauma registries in disaster settings is require.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thanks Katie Lobner, Clinical Informationist at Welch Medical Library, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, for her assistance with the literature search.Appendix 1

Search Terms

Appendix 2

PRISMA Checklist

References

- The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. 2004. (Accessed December 20, 2012, at https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf.)

- NCIPC: Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). (Accessed December 20, 2012, at https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars.)

- American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank. (Accessed December 20, 2012, at https://https://www.ntdbdatacenter.com/Default.aspx.)

- Bai XD, Liu XH. Retrospective analysis: the earthquake-injured patients in Barakott of Pakistan. Chin J Traumatol. 2009 Apr;12(2):122-4. PubMed PMID:19321059.

- Farfel A, Assa A, Amir I, Bader T, Bartal C, Kreiss Y, Sagi R. Haiti earthquake 2010: a field hospital pediatric perspective. Eur J Pediatr. 2011 Apr;170(4):519-25. PubMed PMID:21340487.

- Gueri M, Alzate H. The Popayan earthquake: A preliminary report on its effects on health. Disasters 1984;8:18-20.

- Iskit SH, Alpay H, Tuğtepe H, Ozdemir C, Ayyildiz SH, Ozel K, Bayramiçli M, Tetik C, Dağli TE. Analysis of 33 pediatric trauma victims in the 1999 Marmara, Turkey earthquake. J Pediatr Surg. 2001 Feb;36(2):368-72. PubMed PMID:11172437.

- Reyes Ortiz M, Roman MR, Latorre AV, Soto JZ. Brief description of the effects on health of the earthquake of 3rd March 1985 - Chile. Disasters 1986;10:125-40.

- Sabzehchian M, Abolghasemi H, Radfar MH, Jonaidi-Jafari N, Ghasemzadeh H, Burkle FM Jr. Pediatric trauma at tertiary-level hospitals in the aftermath of the Bam, Iran Earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006 Sep-Oct;21(5):336-9. PubMed PMID:17297904.

- Sánchez-Carrillo CI. Morbidity following Mexico City's 1985 earthquakes: clinical and epidemiologic findings from hospitals and emergency units. Public Health Rep. 1989 Sep-Oct;104(5):482-8. PubMed PMID:2508177.

- Sarisözen B, Durak K. Extremity injuries in children resulting from the 1999 Marmara earthquake: an epidemiologic study. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003 Jul;12(4):288-91. PubMed PMID:12821848.

- Xiang B, Cheng W, Liu J, Huang L, Li Y, Liu L. Triage of pediatric injuries after the 2008 Wen-Chuan earthquake in China. J Pediatr Surg. 2009 Dec;44(12):2273-7. PubMed PMID:20006008.

- Zhao J, Shi Y, Hu Z, Li H. Sichuan earthquake and emergency relief care for children: report from the firstly arrived pediatricians in the epicenter zone. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011 Jan;27(1):17-20. PubMed PMID:21178813.

- Cassidy LD. Pediatric disaster preparedness: the potential role of the trauma registry. J Trauma. 2009 Aug;67(2 Suppl):S172-8. PubMed PMID:19667854.

- Nwomeh BC, Lowell W, Kable R, Haley K, Ameh EA. History and development of trauma registry: lessons from developed to developing countries. World J Emerg Surg. 2006 Oct 31;1:32. PubMed PMID:17076896.

- WHO. Guidelines for trauma quality improvement programmes. 2009. Available at https://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597746_eng.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2013.

- Bartels SA, VanRooyen MJ. Medical complications associated with earthquakes. Lancet. 2012 Feb 25;379(9817):748-57. PubMed PMID:22056246.

- Briggs SM. Earthquakes. Surg Clin North Am. 2006 Jun;86(3):537-44. PubMed PMID:16781268.

- Bai XD, Liu XH. Retrospective analysis: the earthquake-injured patients in Barakott of Pakistan. Chin J Traumatol. 2009 Apr;12(2):122-4. PubMed PMID:19321059.

- American College of Surgeons. National Trauma Data Bank Pediatric Report. 2012.Available at https://www.facs.org/trauma/ntdb/pdf/ntdb-pediatric-annual-report-2012.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2013.

- International Classification of Diseases, 9th Rev. (ICD-9). 1999. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9.htm Accessed 26 Aug 2013.

- Copes WS, Sacco WJ, Champion HR, Bain LW. Progress in Characterising Anatomic Injury. 33rd Annual Meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; Baltimore, MA, USA p. 205-18.

- Pan American Health Organization. Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief: Haiti Response. Available at https://new.paho.org/disasters/dmdocuments/HealthResponseHaitiEarthq.pdf. Accessed 18 October 2013.

- WHO Family of International Classifications (FIC). International Classification of External Causes of Injuries (ICECI). https://www.rivm.nl/who-fic/ICECIeng.htm. Accessed 7 November 2013.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.