Methods: We focused on four steps: #1: Appraising the emergency management research portfolio of VHA-based researchers; #2: Obtaining systematic information on VHA’s role in emergency management and the healthcare needs of veterans during disasters; #3: Based upon gaps between the current research portfolio and the existing evidence base, identifying strategic priorities using a research agenda-setting conference; and #4: Laying the groundwork to foster the conduct of emergency management research within VHA.

Results: Identified research priorities included how to prevent and treat behavioral health problems related to a disaster, the efficacy of training programs, crisis communication strategies, workforce resilience, and evacuating veterans from health care facilities.

Conclusion: VHA is uniquely situated to answer research questions that cannot be readily addressed in other settings. VHA should partner with other governmental and private entities to build on existing work and establish shared research priorities.

]]>Introduction

In addition to providing healthcare for veterans, the United States Veterans Health Administration (VHA), part of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), is charged with improving the Nation’s preparedness for response to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters by developing plans and taking actions to ensure continued service to veterans, as well as supporting national, state, and local emergency management, public health, safety and homeland security efforts.1,2,3 Under the National Response Framework of the United States (U.S.), VHA has support responsibility under 7 of the 15 Emergency Support Functions including emergency management, public health, and medical services. Consequently, VHA has directly provided care for veterans—and sometimes non-veterans—during every major national disaster since 1992.

By law, VHA provides health care to enrolled Veterans first, but can provide support to communities when there are local emergency needs or federally declared disasters. In this capacity, VA’s extensive resources as the largest integrated healthcare delivery system in the U.S. (more than 350,000 personnel at more than 1,300 medical sites serving about 9 million Veterans) may be used to support other Federal and state agencies and local communities by providing public health and medical services following emergencies and disasters. For example, VA deployed more than 1,300 personnel and 12 mobile clinics to Louisiana and Mississippi following Hurricane Katrina; the clinics provided care to about 15,000 patients, including 11,000 who were not Veterans. The VA also provide significant amounts of care to individuals impacted by events as diverse as the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001,4 and the earthquake in Haiti that occurred in 2010. VA staff regularly participate in emergency planning for events such as domestic Olympics, Presidential Inaugurations, and Papal visits.

In mid-2008, VHA’s Office of Public Health (OPH, now part of the VHA Office of Patient Care Services) provided funding to researchers at the Health Services Research & Development (HSR&D) Center of Excellence for the Study of Healthcare Provider Behavior to develop a plan to establish a comprehensive, VHA emergency management research and program evaluation agenda. It was hoped that the agenda would provide a basis for fostering the conduct of more VHA-based emergency management research, and, over time, position VHA as a national leader in emergency management research. This paper summarizes the process and outcomes of this effort, and outlines VHA’s research and evaluation priorities.

VHA Emergency Management Research Agenda-Setting Process

Emergency management professionals and researchers with significant funded or published research on emergency preparedness were invited to join a conference wherein attendees would assist in the creation of a research agenda designed to address gaps in research on VHA emergency management. The planning group operated within the framework of a four-step action plan adapted from Yano and colleagues (2006)5 for a VHA Women’s Health Research Agenda-Setting Conference (Table 1).

Action Plan

Approach

Step #1: Critically appraise the VHA emergency management research portfolio

1. Obtain and review history of emergency management funding to VHA researchers; 2. Analyze data by funding source (e.g., VHA, other federal, private, foundation)

Step #2: Obtain systematic information about VHA emergency management to provide an evidence base for the research agenda

Conduct a systematic VHA emergency management literature review, including review of grey literature as well as peer-reviewed literature

Step #3: Based on gaps between the current VHA research portfolio (step #1) and the assessment of the evidence base (step #2), identify priorities for a VHA emergency management research agenda

1. Review and adapt priority-setting strategies by other agencies (e.g., Department of Defense, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention); 2. Review VHA strategic plans3. Conduct gap analysis, priority setting, and consensus development during a VHA emergency-management research agenda setting conference (held July 2009)

Step #4: Foster the conduct of VHA emergency management research

1. Build research capacity through collaboration, networking, and mentoring; 2. Increase awareness and visibility of VHA emergency management research

Appraisal of VHA’s Research Portfolio

To support strategic planning, it was necessary to assess the current state of existing emergency management research within VHA. This historical research portfolio provides a foundation for the reader to understand both the nature and scope of the then current VA emergency management research portfolio upon which the conference planning and subsequent research agenda were based. The following section reviews emergency management research funding secured by VHA researchers through 2008.

Emergency Management Funding

During 2003-2008, VHA researchers based at one of the HSR&D Centers of Excellence were funded by HSR&D and the VHA Office of Mental Health Services, and non-VHA sources, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Table 2).

Fiscal Year

VHA

Non-VHA

Total

2003

$354,279

$131,500

$485,764

2004

$441,336

$851,859

$1,293,195

2005

$489,235

$466,395

$955,630

2006

$523,910

$958,709

$1,482,619

2007

$385,896

$598,982

$984,878

2008

$0

$1,370,472

$1,370,472

Total Number of Studies: 6

Total Number of Studies: 11

VHA-funded emergency management research increased steadily from 2003 to 2006, then decreased by more than 25% in 2007. No VHA researchers were funded by VHA to conduct emergency management research during 2008. Non-VHA funding increased more than sixfold from 2003 to 2004, then decreased by about half the following year. From 2006 to 2008, non-VHA funding to VHA researchers who study emergency management continued to fluctuate. Some of the fluctuation in funding from year to year during this time period may be due to the cyclical nature of funding related to the occurrence of major disasters. For example, it is likely that the increase in funding for emergency management research in 2005 and 2006 was a response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

It is evident from this review that emergency management is an emerging area of research in terms of VHA funding. As shown in Table 3, emergency management funding has remained relatively constant at under one percent of total funding to VHA researchers based at HSR&D Centers of Excellence. In comparison, former emerging VHA research topics such as women veterans’ health started at approximately 2-3% of total funding to VHA researchers.5 Subsequent to the VHA Women’s Health Research Agenda-Setting Conference in 2004, women’s health was identified as a VHA research priority, leading to an increase in funding for women veterans’ health research.

Emergency management research funding

Total research funding

% of Total

2005

$955,630

$160,750,113

0.6%

2006

$1,482,619

$156,282,076

0.9%

2007

$984,878

$165,994,469

0.6%

2008

$1,370,472

$170,103,121

0.8%

In summary, the total amount of emergency management research funding secured by VHA researchers stayed relatively constant from FY 2004 to FY 2008, although VHA funding declined to zero in FY 2008. Non-VHA funding decreased in FY 2005, but increased again beginning in FY 2006. VHA funding comprised 34%-73% of the total funding VHA emergency management researchers secured from FY 2003 to FY 2007. NIH was the primary sponsor of this type of research during FY 2007 and FY 2008.

The number of VHA-based researchers funded by VHA sources increased from 9 during FY 2003 to a high of 27 in FY 2007, before declining to zero during FY 2008. In contrast, the number of VHA-based researchers funded by non-VHA sources increased from 1 during FY 2003 to a high of 6 during FY 2007, before dropping to 3 during FY 2008.

The decline in VHA funding in FY 2008 in part reflects the small number of studies in progress during this time period, and suggests a need for more consistent funding in this area in order to attract and grow the emergency management research community within VHA. These trends suggest a clear interest among the VHA community for conducting research in the area of emergency management, but one that is limited by cyclical factors such as variations in funding over time.

Establishing the Evidence Base for Agenda Development

Research Portfolio

A review of HSR&D-funded studies provides a broad overview of emergency management issues confronting VHA. A systematic search within VHA databases identified six HSR&D-funded studies since 2002. One of the six studies focused on surveillance, two on education, and three on the response to bioterrorism or natural disasters (two of which focused on vulnerable populations).

Summary of HSR&D Studies

The six HSR&D-funded studies since 2002 are limited in scale and scope (Table 4). The one surveillance study points to the importance and usefulness of automated monitoring of electronic health information in early illness detection. The two educational studies, involving providers and patients, indicate an existing need to adapt educational interventions to the VHA population. Of the three response studies, two evaluated actual events and one involved scenario-modeling. Collectively, they addressed VHA’s ability to compare responses across locations and time, the ability to study vulnerable populations, and the recognition of VHA as a potential target due its governmental affiliation.

PI

Background

Objective

Methods

Findings

S. Delisle(IIR 06-119)

Early detection is critical for infectious disease outbreaks of public health importance. Disease surveillance can be potentially enhanced through automated monitoring of electronic medical records compared to manual case reporting systems

To automate the use of data from VHA’s computerized patient record system (CPRS) to enhance outbreak detection by including illness progression and severity to reduce “noise” of common syndromes

Clinical data was grouped by respiratory disease severity using diagnostic and procedures notes, laboratory results, and free text of clinical notes

Automated surveillance for influenza should integrate information from prescriptions and free text clinical notes. Case detection with emergency medical records focusing on influenza-like cases with fever can reduce delay and workload to detect influenza epidemics

C. I. Kiefe(BTI 02-092)

The VHA medical system can play an essential role following a biological terrorist attack or infectious outbreak due to its extensive record in disaster preparedness

To develop and test web-based teaching modules to increase VHA clinicians’ knowledge about biological warfare agents

Web-based educational intervention was tested at 15 VHA facilities via a randomized controlled trial with 332 participants

The VHA program demonstrated higher anthrax, but not smallpox, post- training provider knowledge than the information offered on the CDC’s website

M. Sano(BTI 02-233)

Limited efforts to prepare general public for a bioterrorism incident have been conducted

To develop educational materials for veterans about bioterrorism; to provide coping mechanisms for getting though a bioterrorism incident; to evaluate methods for material delivery

A Veterans’ Survey on Bio-Terrorism (VSOB) (the initial and a follow up) was mailed to 2923 veterans

VSOB, the first instrument to evaluate veterans’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, anxiety and educational needs connected to bioterrorism, was developed

A. Dobalian(RRP 06-134)

Existing research within and outside of VHA does not sufficiently address health issues for mentally ill and/or frail veterans during evacuations

To understand evacuation and response in VHA nursing homes after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita

Data were collected via 13 semi-structured interviews with organizational representatives at 4 VHA medical centers and two representatives at the regional level

Administrators primarily relied on local resources, prior experience and local planning rather than on state and federal response systems in their response to the hurricanes. Despite significant difficulties during patient evacuation, VHA response was generally perceived as positive. Retaining staff and a viable organization during and after a disaster presented a difficulty. Respondents reported unaddressed preparedness needs even more than one year post-disaster

F. M. Weaver(RRP 06-135)

Individuals with spinal cord injuries and disorders are at particular risk during disasters due to impaired mobility and special needs, such as power wheelchairs and ventilator dependency

To use identified lessons learned from natural disasters that impacted veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders (SCI&D) in developing a toolkit, which focuses on enhancing natural disaster preparedness for facilities caring for veterans with SCI&D

Thirty interviews were conducted (16 with providers and 14 with veterans with SCI&D). Most interviewees had experienced at least one weather-related natural disaster

Veterans with SCI were usually evacuated to unaffected areas or were admitted to SCI centers. Previous disaster experiences provided lessons to guide providers’ and veterans’ actions. Pre-established response plans served as useful starting points. Family and local agencies’ social support was essential for veterans to attain a sense of personal preparedness. The above information was used to develop tools for disaster preparedness.

B. Schmitt(IIR 02-080)

VHA is particularly vulnerable to a postal attack directed at government facilities. Thus, it has an interest in identifying the most advantageous response to small and large-scale bioterrorist events

To conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis comparing response strategies to a small and a large-scale anthrax attack

A decision analytic model was used to compare 3 basic response strategies to a small scale anthrax attack. The optimal response to a mass inhalation anthrax attack was evaluated. Outcomes included costs, Quality-Adjusted Life Years, and incremental cost-effectiveness

For the small-scale anthrax attack, the least costly strategy was administration of antibiotics post-attack; post-attack antibiotic and post-attack vaccination strategy was the most effective. Pre-attack vaccination was the least effective. Pre-attack vaccination was preferable to post-attack antibiotics alone when the probability of anthrax exposure was ≥16%. For the large-scale mass attack scenario, analysis is in progress

Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review was conducted to synthesize what is known about VHA emergency management research. Specifically, the review answered the following research questions: 1. What is the role of VHA in emergency management, including mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery? 2. For each of the identified VHA emergency management activities, what recommendations (“lessons learned”) were made to improve the activity around mitigation, preparedness, response & recovery? 3. What veteran health needs have been identified as important in emergency management? Results of the review are presented elsewhere.6

Achieving Consensus on Research Priorities

The purpose of the VHA Comprehensive Emergency Management Program Evaluation and Research Conference was to bring together researchers and practitioners in a common forum to discuss and make recommendations regarding the direction of future VHA program evaluation and research on emergency management. Participant affiliations included VHA, various universities, CDC, the Department of Defense, NIH, and AHRQ, and other institutions.

After several context-setting presentations about VHA’s role in emergency management, attendees participated in one of five workgroups: Behavioral Health (e.g., mental health; substance use/abuse; psychological first aid; the “worried well”); Workforce (e.g., education/training of personnel; VHA’s Disaster Emergency Medical Personnel System (DEMPS); competing family concerns); Communication and Information Flow (e.g., decision-making; inter-organizational collaboration; risk communication); Sustainability and Resilience (e.g., quality improvement; community resilience); and Systems Capabilities (e.g., broad health systems issues such as evacuation, pandemic influenza; methodological considerations when conducting research in this field; inter-organizational collaboration).

VHA’s Emergency Management Research Agenda

Behavioral Health

The Behavioral Health workgroup (e.g., mental health; substance use/abuse; psychological first aid; the “worried well”) was tasked with identifying and prioritizing VHA emergency management research issues related to the mental health needs of individuals impacted by a disaster or mass casualty event. While the conversation did include some discussion of VHA workforce needs (e.g., training and psychological support) as well as the mental health impacts of disasters on VHA and VHA’s role in providing care for the larger community, most of the workgroup’s discussion focused on preventing and treating post-disaster development or exacerbation of behavioral health problems in the veteran population. Because VHA provides ongoing medical and support services for many veterans with psychological and substance use disorders, addressing the impact of large scale emergencies and disasters on behavioral health needs was considered to be of particular significance to VHA.

Priorities

Key Questions/Research Topics

Workforce

The Workforce workgroup (e.g., education/training of personnel; Disaster Emergency Medical Personnel System (DEMPS)9; competing family concerns) focused on issues regarding: designing and evaluating effective education and training strategies for health care personnel, establishing competency guidelines, effectively engaging health care providers in decision making related to emergencies, DEMPS teams, and how to address employees’ competing concerns for the safety of their own family members. There was a general consensus that a fair amount of funding has been dedicated to training and education, but that rigorous research about the effectiveness of training and education programs is lacking. Furthermore, future effectiveness research should differentiate demonstrating competencies of individuals from system capacity, which is dependent on infrastructure. The workgroup recognized the importance of VHA’s work with various federal partners, and that the manner in which it interacts with other federal agencies is a critical area of research regarding workforce issues.

Priorities

Key Questions/Research Topics

Communication & Information Flow

The Communication and Information Flow workgroup (e.g., decision-making; inter-organizational collaboration; risk communication) focused on a wide array of topics related to emergency management planning issues within VHA, specifically crisis communication, risk communication, communication tools, and community collaboration applicable to the overall healthcare system, veterans, staff, and the community. The group expressed the potential concern that VHA’s organizational culture may be overly driven by protocols and standards, and questioned whether communication could effectively be structured to make and disseminate clinical and strategic decisions to veterans, staff, and local communities in an effective and time-efficient manner given these concerns. The group indicated that it would be valuable to identify triggers that lead to the effective dissemination of information from VHA to the public, and wondered how those mechanisms would be altered by a public health emergency. In this regard, the workgroup noted that VHA could also draw on the expertise of its federal and other partners.

Priorities

Key Questions/Research Topics

Sustainability and Resilience

The Sustainability and Resilience workgroup (e.g., dual-use systems that may improve the quality of care delivered outside of a disaster situation as well as in the event of an emergency; community resilience) met to discuss the sustainability of resources for emergency preparedness and response, and was asked to consider areas in which to invest scarce resources; quality and cost; how to leverage existing systems or to establish “dual-use systems” that provide benefits both under non-emergent and emergent situations; challenges related to the ebb and flow of funding related to the recency and size of a domestic disaster; and the resilience of veterans and VHA, as well as community resilience in general. The workgroup stressed the importance of disaster research funding and recommended that such funding be increased as a prerequisite for a successful emergency management research agenda and its ongoing implementation.

Priorities

Key Questions/Research Topics

Systems Capabilities

The Systems Capabilities workgroup (e.g., broad health systems issues such as evacuation, pandemic influenza; methods; inter-organizational collaboration) discussed the broader healthcare system and population issues applicable to all healthcare systems, although it focused primarily on VHA-specific issues while considering both internal and external concerns. Using both experience with current practices, including a discussion of actual operational decisions made during the response by VHA and others to Hurricane Katrina, as well as an assessment of current gaps in the field’s understanding, this workgroup identified various research priorities. Much of the workgroup’s discussion concerned the potential for VHA to become a leader in developing evidence-based standards for emergency management. The workgroup noted that VHA’s facilities and other resources provide an invaluable “laboratory” to strengthen national emergency management research capabilities. Resources noted by the workgroup included the recognition that VHA facilities that provide care for the most complex inpatient cases are required to have academic resource centers in their facilities. In addition, VHA staff with a military background often have experience either training for or actually having responded to a disaster. Furthermore, VHA currently makes resources available to the local community, including pamphlets that describe how to respond to a local emergency, and plays an extensive role in national emergency response. Finally, in rural areas, VHA may be the sole federal presence in the community and is often relied upon as the primary source of federal distribution, care and support. Members of the workgroup who had been part of the Katrina response also discussed issues surrounding surge capabilities where healthcare workers from neighboring institutions were farmed out to distant facilities because their hospitals were closed.

Priorities

Key Questions/Research Topics

Building an Infrastructure for Fostering the Conduct of VHA Emergency Management Research

Based on the first three steps, the research team recommended a variety of measures to assure that there is adequate infrastructure within VHA to support the implementation of the research agenda. We recommended that a VHA agenda-setting process be reconvened within five years to assess progress on implementing the agenda and to establish new directions for subsequent years. The current research agenda was developed based on the best available data at the time. We anticipate that VHA’s investments in emergency management program evaluation and research will continue to yield rapid advances. This translates into a rapidly changing landscape, and a new set of knowledge and investigators who should be brought together to reappraise, re-energize, and recommit to the next phase of VHA emergency management evaluation and research. Although an updated agenda-setting conference has not been reconvened as of 2016, the initial conference was followed in subsequent years by annual meetings (Advancing and Redefining Communities for Emergency Management) that continue to bring together VA and non-VA researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers to share evidence-based practices and discuss the current state of emergency management research.

Some key differences exist between the VHA and other hospitals and healthcare facilities. For example, VHA has a well-integrated electronic medical system. Private facilities have begun to expand these capabilities in recent years. Electronic medical systems have advantages, but do require power to operate, and thus may require paper backups or other options during some disasters. In addition, VHA has a wide array of facilities that serve various populations, including residential facilities that serve Veterans with substance use disorders and various residential facilities for homeless Veterans.

In addition, it was recommended that efforts be made to increase the visibility of VHA’s emergency management research and its potential to serve as a laboratory for emergency management research for the Nation. Hospital systems often focus on healthcare-related issues at the expense of applying findings from the broader disaster-related literature.22,23,24 It was hoped that issues such as this could be explored within VHA for the benefit of both VHA and the nation. In particular, VHA should maintain and expand a searchable database of published articles and unpublished reports related to VHA emergency management program evaluation and research that would provide support to VHA researchers interested in VHA emergency management research opportunities and collaborations. This effort could lead to the establishment of a multi-component, web-based emergency management evaluation resource clearinghouse that would make emergency management research and evaluation resources more readily available and accessible to researchers and practitioners. Similarly, the establishment of a VHA Comprehensive Emergency Management Program Evaluation Center would enhance VHA’s mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery activities in the event of emergencies and disasters. The Center’s goal should be to develop an evidence base by which VHA contributes to the development, evaluation and improvement of healthcare services and programs that (1) strengthen VHA’s CEMP, and (2) position VHA as a national leader in emergency preparedness and response. As a result of these recommendations, VHA established the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center (VEMEC) in July 2010. VEMEC continues to this day.

Conclusions

Using a systematic evidence base and consensus development process among stakeholders within and outside VA, we report on the first national VA comprehensive emergency management program evaluation and research agenda. VA provides a unique national laboratory for the conduct of high quality research that will improve VA’s and our Nation’s emergency medical and public health preparedness and the role of health delivery systems in that endeavor. To effectively foster the conduct and expansion of emergency management evaluation and research within VA, the consensus was that VA needs to build program evaluation capacity, increase the awareness and visibility of VA’s emergency management research, and build bridges to research partners at agencies and organizations with longstanding commitments to advancing emergency management research.

Corresponding Author

Aram Dobalian: [email protected]

Competing Interests

The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability

All relevant data are available from the figshare repository: https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3085807.

Methods: SPEED reports medical consultations based on 21 syndromes covering a range of conditions from three syndrome groups: communicable diseases, injuries, and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). We analyzed consultation rates for 150 days post-disaster by syndrome, syndrome group, time period, and health facility type for adults as well as for children under the age of five.

Results: Communicable diseases had the highest consultation rates followed by similar rates for both injuries and NCDs. While communicable diseases were the predominant syndrome group for children, wounds and hypertension were common syndromes observed in adults. Village health centers had the most consultations amongst health facilities, but also showed the highest variability.

Discussion: Children were more vulnerable to communicable diseases compared to adults. Community health centers showing consistently high consultation rates point out a need for their prioritization. The predominance of primary care conditions requires disaster managers to focus on basic health care and public health measures in community health centers that target the young, elderly and impoverished appropriate to the time period.

]]>Introduction

Typhoon Haiyan was a category five typhoon, which made landfall in the Philippines on November 8, 2013. It made 6 landfalls in the Visayas and Palawan and caused considerable damage to these regions. It affected around 16 million people and killed more than six thousand.1,2 It is considered a sudden onset disaster with prolonged health consequences.1,3

The Health Emergency Management Bureau (HEMB) of the Philippine Department of Health (DOH) activated the Surveillance in Post Extreme Emergencies and Disasters (SPEED) during the response to Typhoon Haiyan. SPEED is a syndromic surveillance system for health facilities that monitors 21 syndromes. Reports can be transmitted manually, via mobile or the Internet. SPEED runs in parallel with the regular epidemiologic reporting system of the DOH. SPEED’s database records consultation rates for 21 syndromes. It enables early detection of communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases, and injuries, monitors syndrome trends, and guides the DOH’s disaster response.4,5

Typhoon Haiyan was a distinct event that disrupted health systems of various regions. Ensuing storm surge caused most of the damage to the population and infrastructure, such as water, electricity, and telecommunication. Typhoon Haiyan dealt a severe blow to the public health system with damages to the tune of 26 million US dollars (USD). The damage to the health infrastructure including 42 hospitals, 95 community health centers and 427 village health centers alone accounted for 19.2 million USD.1,6

Typhoons in general can pose a risk for the outbreak of infectious diseases. Such outbreaks are usually endemic to the affected area and not unfamiliar to the local medical personnel. Expected diseases include watery diarrhea, acute respiratory infections, measles, malaria and dengue. The environmental conditions of overcrowding, increased vector spread, lack of clean drinking water, and hygiene facilities contribute to these conditions.7,8,9,10 Thus humanitarian organizations prioritize these infectious diseases in their disaster response.11

Although the DOH and the World Health Organization (WHO) issued publications on Typhoon Haiyan none of these studies include a detailed account of the disaster’s health impact.1,2,6 In 2015 Martinez et al. analyzed SPEED and conducted focused group discussions to show the health impact of non-communicable diseases during Haiyan.12 In 2016 Salazar et al. used the SPEED database to, analyze the health impact of three disasters from 2013 including Typhoon Haiyan. This analysis, however, did not give detailed information on individual syndromes, health facilities, and children.10 The main objective of this study is to analyze the health impact of communicable diseases, injuries, and non-communicable diseases (NCD) during Typhoon Haiyan using the SPEED database including descriptions of individual syndromes and the use of health facilities by different age groups during disaster response and recovery.

Methods

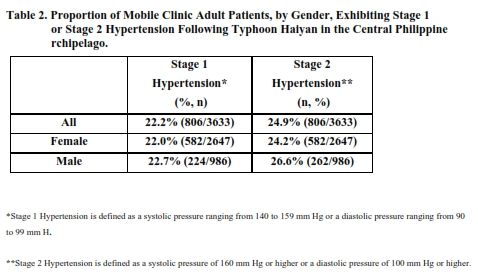

This is a descriptive study of an existing database of the Health Emergency Management Bureau. SPEED uses aggregated data from health facilities in disaster affected areas. This study analyzes SPEED data from health facilities in the Eastern Visayas region, one of the four regions affected by Typhoon Haiyan, from November 8, 2013 to March 28, 2014.6

The database comprises reports that detail the number of consultations per day by health facility for two age groups (<5 vs. ≥5 years of age).4 This study categorizes all syndromes into three groups: communicable diseases, injuries, and NCDs similar to the study by Salazar et al. from 2016.10 Communicable diseases include the following syndromes: acute bloody diarrhea, acute flaccid paralysis, acute hemorrhagic fever, acute jaundice syndrome, acute respiratory infection, acute watery diarrhea, animal bites, conjunctivitis, fever, fever with other symptoms, skin disease, suspected leptospirosis, suspected measles, suspected meningitis, and tetanus. Fractures and wounds, including bruises and burns are considered syndromes for injuries. The following are syndromes for NCD’s: acute asthmatic attack, acute malnutrition, high blood pressure, and known diabetes mellitus.4,10

To calculate consultation rates per day according to health facility, age group as well as all ages combined, we divided the respective number of consultations by the corresponding population of the catchment area of each health facility. The catchment area was estimated according to the type of health facility i.e. village health centers, community health centers, hospitals, evacuation centers, mobile clinics, foreign medical team clinics, and foreign medical team hospitals. For village health centers and evacuation centers the village population was defined as the catchment area. For community health centers and hospitals the municipality or city population was used. Less observed health facility types (mobile clinics 1%, foreign medical team clinics 2%, and foreign medical team hospitals 0.4%) were merged with the best fitting group as follows: mobile clinics and foreign medical team clinics with village health centers and foreign medical team hospitals with hospitals. The population data used is based on the 2010 census from the Philippine Statistics Office.13,14

Mean consultation rates per day with 95% confidence intervals and t-tests comparing age groups and time periods were calculated using Stata Version 13.15,16 Scatter plots and splines were used to visualize the trend in syndrome morbidity. Splines are based on regressions, joining points to fit a particular shape.17 Consultation rates were presented per 10,000 individuals per day as this number is routinely used in the literature for emergency health kits.10,18 Additionally, rates within two months (≤60 days) were compared to rates after two months (>60 days) as this was identified to separate response and recovery.10

As this is a descriptive study of an existing database using aggregated data, the Institutional Review Board of Heidelberg University deemed the study exempt from full review. Prior to the start of the study, the SPEED database for Typhoon Haiyan was requested from the director of HEMB. HEMB did an initial validation of the Haiyan data.10 All SPEED database reports were handled with confidentiality by the authors of this study. SPEED consists of aggregated data from health facilities, which does not include individual patient information, thus also ensuring the confidential and anonymous nature of the database.

Results

As part of disaster disease surveillance conducted by HEMB and DOH, there were 3,425 SPEED reports for Typhoon Haiyan in the Eastern Visayas region within 150 days post-disaster. For mean rates, communicable diseases had overall the highest rates, 47.3 per 10,000 individuals, followed by similar rates for both injuries (5.9) and NCDs (6.0). Looking at consultation rates over time, the representative syndromes for communicable diseases, injuries, and NCDs are acute respiratory infections, wounds, and high blood pressure respectively. These syndromes were selected because they had the highest rates among all syndrome groups (see Table 1). The spline and scatter plot shows a peak in consultation rates around day 20 to 25 for all three syndromes. Thereafter, rates decrease and stabilize around day 50 post-disaster. Acute respiratory infections showed a much more prominent increase in consultation rates compared to wounds and high blood pressure (see Figure 1).

Table 1: Syndrome rates per 10,000 individuals separated by time post-disaster and by age

Syndrome

Total

≤ 2 months

> 2 months

Difference between ≤ 2 months and > 2 months

< 5 years of age

≥ 5 years of age

Difference between < 5 years and ≥ 5 years

Communicable diseases

Acute respiratory infection

36.0

64.0

11.1

52.9 (p<0.01)

112.4

25.6

86.9 (p<0.01)

Skin disease

4.5

8.2

1.2

7.0 (p<0.01)

13.8

3.2

10.5 (p<0.01)

Acute watery diarrhea

2.5

4.6

0.6

4.0 (p<0.01)

11.4

1.3

10.0 (p<0.01)

Fever

2.3

4.1

0.7

3.4 (p<0.01)

8.4

1.4

6.9 (p<0.01)

Fever with other symptoms

0.8

1.3

0.3

1.0 (p<0.01)

1.4

0.7

0.7 (p=0.06)

Animal bites

0.5

0.8

0.2

0.6 (p=0.03)

1.1

0.4

0.8 (p=0.11)

Conjunctivitis

0.3

0.5

0.1

0.4 (p<0.01)

0.5

0.3

0.2 (p=0.19)

Suspected leptospirosis

0.1

0.3

<0.1

0.3 (p=0.01)

0.2

0.1

0.1 (p=0.52)

Acute bloody diarrhea

0.1

0.2

<0.1

0.2 (p<0.01)

0.3

0.1

0.3 (p=0.01)

Suspected meningitis

0.1

0.2

<0.1

0.2 (p=0.24)

0.1

0.1

<0.1 (p=0.78)

Suspected measles

0.1

0.1

0.1

<0.1 (p=0.47)

0.5

<0.1

0.4 (p=0.07)

Acute hemorrhagic fever

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.34)

0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.28)

Acute jaundice syndrome

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.04)

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.03)

Tetanus

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.12)

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.18)

Acute flaccid paralysis

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.02)

<0.1

<0.1

<0.1 (p=0.03)

Communicable disease total

47.3

84.5

14.2

70.3 (p<0.01)

150.2

33.3

116.9 (p<0.01)

Injuries

Open wounds & bruises/burns

5.8

10.7

1.4

9.3 (p<0.01)

6.2

5.7

0.4 (p=0.74)

Fractures

0.1

0.2

<0.1

0.2 (p=0.01)

0.3

0.1

0.2 (p=0.25)

Injury total

5.9

10.9

1.4

9.5 (p<0.01)

6.4

5.8

0.6 (p=0.65)

Non-communicable diseases

High blood pressure

4.7

8.0

1.8

6.2 (p<0.01)

0.1

5.4

5.3 (p<0.01)

Acute asthmatic attack

0.9

1.6

0.3

1.3 (p<0.01)

2.0

0.8

1.2 (p<0.01)

Known diabetes mellitus

0.4

0.7

0.1

0.6 (p<0.01)

<0.1

0.4

0.4 (p<0.01)

Acute malnutrition

<0.1

0.1

<0.1

0.1 (p=0.04)

0.2

<0.1

0.2 (p=0.22)

NCD Total

6.0

10.3

2.3

8.1 (p<0.01)

2.2

6.6

4.3 (p<0.01)

Fig. 1: Consultation rates per 10,000 individuals for acute respiratory infections, wounds, and hypertension.

A similar number of reports was observed within two months (n=1,614) and after two months (n=1,811) post-disaster. Within two months post-disaster, acute respiratory infections also accounted for the highest consultation rates with 64.0 per 10,000 individuals. Wounds and hypertension had consultation rates of 10.7 and 8.0 per 10,000 individuals respectively. After two months post-disaster the rates for all three syndromes were significantly lower: acute respiratory infections (11.1), wounds (1.4), and hypertension (1.8).

Rates for the whole 150-day period decreased in the following order: acute respiratory infections, open wounds, high blood pressure, skin disease, acute watery diarrhea, and fever. Within two months post-disaster, eight syndromes showed consultation rates higher than 1 per 10,000 individuals compared to six for the whole period. The additional two syndromes were acute asthmatic attack and fever with other symptoms. After two months post-disaster, only four syndromes were above 1 consultation per 10,000 individuals per day. These were acute respiratory infections, open wounds, high blood pressure, and skin disease. Comparing consultation rates for these two periods all syndromes show higher consultation rates in the first two months post-disaster. Only four syndromes displayed differences with p values greater than 0.05; these were meningitis, suspected measles, acute hemorrhagic fever, and tetanus. The top eight syndromes: acute respiratory infections, open wounds, hypertension, skin disease, watery diarrhea, fever, asthma, and fever with other symptoms showed differences greater than 1 consultation per 10,000 individuals and p values less than 0.01 (see Table 1).

The top eight syndromes showed differences when analyzed according to age group. Acute respiratory infections, skin disease, acute watery diarrhea, and fever showed the highest consultation rates for children under the age of five. Acute respiratory infections had the highest consultation rates for adults followed by wounds, hypertension, and skin disease. Communicable diseases had significantly higher rates in under-five-year old children specifically for acute respiratory infections, skin disease, acute watery diarrhea, and fever. Injuries had similar rates for both age groups. While NCDs in form of hypertension and diabetes were more common for adults, asthma was more common for children under the age of five (see Table 1).

When grouped according to health facility type, most records in SPEED were contributed by community health centers and hospitals with 54% and 30% respectively. Village health centers had the highest consultation rates among the four health facility types and also had the highest variability across time seen in its 95% confidence interval and difference in the mean rates (see Table 2).

Table 2: Consultations per 10,000 individuals per day per health facility

Health Facility Type

# of SPEED reports

Mean with 95% confidence interval

Community Health Center

1850

25.0 (20.3-29.7)

Evacuation Center

39

19.5 (0-43.9)

Hospital

1039

7.0 (6.5-7.6)

Village Health Center

497

299.0 (247.1-350.9)

Discussion

This study provides a detailed analysis of the conditions seen in health facilities in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan. It illustrates that communicable diseases were the most common syndrome group, and that acute respiratory infection was the most common of the 21 syndromes. Under-five-year old children displayed higher rates for communicable diseases, similar rates for injuries, and lower rates for NCDs in comparison with adults. The highest consultation rates recorded came from village health centers followed by community health centers.

Syndromes which were consistent in their consultation rates throughout the whole period, such as meningitis, suspected measles, acute hemorrhagic fever, and tetanus all require referral to tertiary care.19 These syndromes showed rates of less than 0.1 for the whole 150-day post-disaster period, indicating nevertheless a potential risk these syndromes pose during response and recovery periods. The most common syndromes recorded in the SPEED database represented primary care conditions. According to Connelly et al. in 2004, acute respiratory infections and diarrhea, syndromes which were also observed in this study, account for the majority of morbidities in emergencies. Acute respiratory infections and diarrhea are attributed to over-crowding in shelters and lack of quality water services respectively.20

Communicable diseases were more prominent in children under five manifesting as acute respiratory infections, skin disease, acute water diarrhea, and fever. A study concluded in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in the United States in 2005, showed that pediatric consultations included respiratory conditions, skin ailments, and under-nutrition. Respiratory conditions reported were acute respiratory infections and allergic rhinitis while skin conditions included bacterial and fungal infections.21 Furthermore, a systematic review from 2013 showed that the most common pediatric themes found in the literature for emergencies and disasters included infectious conditions, vaccine-treatable diseases, hygiene-related ailments, and wounds.22

As expected NCDs were more visible in adults; hypertension had the third highest rate. Moreover, hypertension and diabetes displayed a significant difference in rates within and after two months post-disaster. Another study on Hurricane Katrina found that 40% of those seeking consultations came because of chronic conditions such as hypertension. 20% came in order to get medication for pre-existing chronic conditions.23 This may be due to an increase in demand for chronic disease treatment because of health system disruption.24 In the case of Typhoon Haiyan, first-line health providers saw that patients with NCDs experienced a lack of supply of medications and basic necessities such as food and clothing.12 The need for basic provisions for survival may have pushed these patients to seek consult for pre-existing conditions thus causing an increase in the consultation rates within the first two months post-disaster.

Haiyan’s mortality profile and magnitude causing disaster response delay contributed to the conditions observed in SPEED. Most storm surge mortalities are due to drowning.25 This is also true for Typhoon Haiyan. In a case control study after the typhoon, which looked into the risk factors associated to mortality, the deaths observed were all due to drowning.26 Since the disaster had a high death toll (6,300 people were killed),1 consultation rates for fractures were low. Open wounds, the more benign syndrome, had the second highest syndrome rate. Moreover, the initial responders were also victims since their health facilities and homes had been destroyed by the typhoon. It took the local responders from neighboring regions two days before they reached the hardest hit areas.1 Furthermore, foreign medical teams needed a minimum of three days after arriving in the country to be operational. The peak of functional number of foreign medical teams was only achieved 22 days post-disaster.3 The delay in the response to Typhoon Haiyan may have shifted the profile of the diseases seen in SPEED to more primary care conditions.

The top syndromes highlighted in this study can be addressed with proper diagnosis, appropriate medications, and wound cleaning & dressing.19 Due to their permanent vulnerability, poor populations and people with chronic conditions should be considered for targeted interventions during response and recovery phases of disasters.24 In general, communicable diseases, injuries, and NCDs can be addressed by providing continuous basic health services, water, sanitation and hygiene, nutrition, public health surveillance, disease control, and proper shelter to vulnerable groups namely poor, young, and elderly patients.10,11,20,27

For most syndromes regardless of need for referral, rates within two months were significantly higher than those after two months. In the case of Typhoon Haiyan, the Interagency Standing Committee downgraded its emergency response level 93 days or three months post-disaster. This was in contrast to the national government decision to move from disaster relief to recovery seven months post-disaster.28 Compared to these bureaucratic decisions by both national and international agencies, SPEED provides an evidence-based junction between disaster response and recovery seen in the trends of consultations post-disaster. The sustained decrease in consultations around day 50 can be constituted as the demarcation between disaster response and recovery based on disease surveillance trends.10

We additionally calculated median values to take into account outliers in the data set, but interpretation of the results remained similar to mean rates. Due to the lower number of SPEED reports for evacuation centers and village health centers the mean rates had wider confidence intervals compared to community health centers and hospitals. This high variability prompts further research in health facility utilization during disasters.

Typhoon Haiyan was a mega-disaster with extensive disruption of the health system. The Eastern Visayas region had 22 hospitals, 53 community health centers, and 113 village health centers damaged comprising 52%, 56%, and 26% respectively of each of the damaged health facility types across all four regions.2 Since SPEED received most data from community health centers and hospitals we suppose that these health facility types were the ones to be still operational. Another explanation might be that disaster managers and health ministry officials prioritized these central health facilities as the main reporting centers due to limited capability of logistics and transportation to get to the village health centers further away. This prioritization of community health centers and hospitals was reflected in the publications of the WHO Philippine Country Office and the DOH on community health centers and hospitals affected by Typhoon Haiyan. Community health centers were described as the focal point of primary health care. The local health executives govern the management of village health centers in their catchment areas through community health centers. Moreover, these act as feeders to nearby hospitals for tertiary care.2,6

This study demonstrates the use of SPEED for planning response and recovery activities. In the prioritization of health facilities to be reconstructed or rehabilitated, we propose that the health facilities showing significantly higher rates of consultations, namely community health centers, should be prioritized immediately. Logistics for required medications and supplies for different age groups should be planned according to their percentage in the local population. Planning for medicines, supplies, and equipment as well as training on protocols for prominent diseases of children and aging populations should be emphasized. These populations are also less mobile thus access to health services, both financial and geographic, should be considered. As children and elderly are more vulnerable to environmental factors such as cold and wet weather,29 priority should be placed on shelter for these populations.

The rates for Typhoon Haiyan should be the benchmark for future planning purposes. Typhoon Haiyan was a category five typhoon and the strongest typhoon ever recorded in Philippine history.2 Thus, for now, it is the best template for preparing for the worst possible scenario.

Being a syndromic surveillance system, SPEED has some inherent limitations with regard to the generalizability of the results of this study. The findings of the study refer to health facility data in the Eastern Visayas region and cannot be interpreted as being representative of the whole population affected. Moreover, the population data used to calculate the consultation rates did not take into account the actual population immediately before or after Typhoon Haiyan. Out-migration from the affected areas has not been taken into account either. With regard to SPEED itself, it has to be noted that in some of the affected areas, the system was not operational until one week post-disaster.5 As the syndromes are not that specific and health facilities were not able to report daily, the results should be read as rough estimates rather than exact values. Thus disaster managers still should also consider their extensive experience and integrate it with the findings of our study.

Conclusions

The predominance of primary care conditions seen in the study may be used for planning for future disasters and signals disaster managers to focus on basic health care and public health measures. The trends observed for consultation rates across time may be used as guides for disaster response and recovery. Interventions targeting young, elderly, and impoverished populations are recommended. Community health centers should be prioritized in recovery and rehabilitation efforts.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Corresponding Author

Miguel Antonio Salazar: [email protected]

Ethics

This study uses the 2013 data from Surveillance in Post Extreme Emergencies and Disasters (SPEED), an existing database using aggregated health facility data of the Health Emergency Management Bureau of the Philippine Department of Health. The authors of the study received the SPEED reports as aggregated data and did not have access to individual patient information.

Data Availability

The data from this study are owned by the Health Emergency Management Bureau of the Department of Health of the Republic of the Philippines. As these are government-owned data, their release is subject to the approval of the Director of the Health Emergency Management Bureau. Requests for this data set may be sent to Director Gloria J. Balboa, MD, MPH, MHA of the Health Emergency Management Bureau via [email protected], or through the following address: Health Emergency Management Bureau, Department of Health, San Lazaro Compound, Tayuman, Sta. Cruz, Manila, 1003 Philippines.

Authors’ Contribution

The authors of this manuscript were involved in the conception and design of the study or have contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data of the study. They were part in its critical revision. They have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

MAS wrote the manuscript, conceptualized the study, interpreted the results, and collated the responses and comments from other authors. AP took part in the conception of the study and analyzing the results. RL was vital in acquiring data and analyzing the results. AP and RL contributed to the revision of the manuscript. VW contributed to the writing of the manuscript, the conceptualization of the study and the analysis of the results.

Commentary

As physicians, we are reminded of Sir William Osler’s 1906 speech to graduating medical students when he asserted that: “Medicine is the only world-wide profession, following everywhere the same methods, actuated by the same ambitions, and pursuing the same end. This homogeneity, its most characteristic feature, is not shared by the law or religion”, nor the “extraordinary solidarity which makes the physician at home in any country.”1

In the century that followed, no other profession has exhibited the influential number of international associations, societies and collaborative efforts as has medicine. The end of the Cold War brought multiple humanitarian crises and the development of international academic and educational training programs designed to prepare humanitarian workers for these complex global tasks. The rigorous curriculum includes the unique roles and responsibilities that healthcare providers have under the Post-World War II Geneva Convention (GC) and International Humanitarian Law (IHL) which ensures their right to international health neutrality.

Historically, war has caused the loss of countless lives and has ravaged the most vulnerable populations, especially women, children, the elderly and disabled. The humanitarian crises that wars create, and the manner in which the world responds, have changed with every generation.2 Present-day healthcare workers in public hospitals and non-governmental organizations in conflict zones have never faced greater risks. In fact, deaths among all humanitarian workers have outnumbered those of UN Peacekeepers in recent years.3

The cross-border territorial wars that dominated the 20th Century have been replaced by endless religious, ethnic and tribal conflicts that produce neither winners nor losers. The war in Afghanistan has raged on since 1979, in Somalia since 1991, and the recent Yemeni civil war since 2015. Yet, there is something especially abhorrent about the current war in Syria that should gain the attention of every healthcare provider and health policy maker. These alarming statistics are reminders of the egregiously barbaric quest of ancient wars, designed to ensure that no survivor would remain to take revenge:

As of June 2016, 757 healthcare personnel have been killed and 382 premeditated attacks have occurred on 269 separate medical facilities across Syria. One-hundred and twenty-two hospitals have been targeted multiple times.4 In the midst of this misery one cannot forget the US targeted aerial bombing of Médecins Sans Frontières hospital in Kunduz Afghanistan in October 2015 that killed 42 people, including 14 MSF staff members, and wounded dozens more.5

We must take notice and stand in solidarity with our healthcare colleagues in Syria where patients, healthcare workers, and hospitals are under constant threat and attack. We have the obligation to ensure that every health care provider, both civilian and military, on either side of the current conflict in Syria, be made aware of the inherent protections provided them under IHL, including the four GCs of 1949, as well as the principles and rules of IHL applicable to the conduct of hostilities, which include the targeting of hospitals and medical facilities. These principles and rules must be upheld.

Healthcare providers of the militaries involved on both sides of the conflict are granted provisions and protections under international laws clearly referenced in The Hague Statement on Respect for Humanitarian Principles (1991), UN Security Council Resolution 2286 on attacks against medical workers (2016) and military manuals of many States. As an example, the Russian Federation’s Military Manual (1990) states that attack against medical personnel constitute a prohibited method of warfare. The Russian Federation’s Regulations on the Application of IHL (2001) states: “Persons protected by international humanitarian law include medical and religious personnel. Attacks against such persons are prohibited.”

As such, healthcare providers, both civilian and military, including the Assad Government and the Russian Federation, must equally recognize that under IHL, their own medical military personnel, activities, units, transports, and hospitals are guaranteed protection against direct attack themselves (see rules 25 to 30 of the ICRC’s customary IHL study, as well as protections in the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols). IHL requires Parties to ensure respect for IHL, including under common Article 1 to the four GCs. Failure to do so leads to risks of moral, ethical and legal consequences as well as penalties for their actions and inactions.

The World Medical Association (WMA) Regulations in Times of Armed Conflict and Other Situations of Violence6 assert that under IHL, healthcare providers can neither commit nor assist violations of IHL, nor take part in any act of hostility; must advocate and provide effective and impartial care to the wounded and sick (without reference to any ground of unfair discrimination, including whether they are the “enemy”); must remind their authorities of their obligation to search for the wounded and sick and to ensure access to health care without unfair discrimination; must not allow any inhuman or degrading treatment of which physicians are aware; must report to a commander or to other appropriate authorities if health care needs are not met; and must give consideration to how health care personnel might shorten or mitigate the effects of the violence in question, for example by reacting to violations of international humanitarian law or human rights law.

WMA summarizes the ethical obligations of physicians as follows:6

During times of armed conflict and other situations of violence, standard ethical norms apply, not only in regard to treatment but also to all other interventions. The medical duty to treat people with humanity and respect applies to all patients. Governments, armed forces and others in positions of power should comply with the GC to ensure that physicians and other health care professionals can provide care to everyone in need in situations of armed conflict and other situations of violence. This obligation includes a requirement to protect health care personnel and facilities. Privileges and facilities afforded to physicians and other health care professionals in times of armed conflict and other situations of violence must never be used other than for health care purposes.

Physicians should recognize the special vulnerability of some groups, including women and children. Provision of such care should not be impeded or regarded as any kind of offence, nor must they ever prosecuted or punished for complying with any of their ethical obligations. Physicians have a duty to press governments and other authorities to ensure they are planning for the protection of the public health infrastructure and for any necessary repair in the immediate post-conflict period. Necessary assistance, including unimpeded passage and complete professional independence, must be granted.

Healthcare Parties must be Identified and protected by internationally recognized symbols such as the Red Cross, Red Crescent or Red Crystal. Hospitals and health care facilities situated in areas where there is either armed conflict or other situations of violence must be respected by all combatants. Physicians must be aware that, during armed conflict or other situations of violence, health care becomes increasingly susceptible to unscrupulous practice and the distribution of poor quality / counterfeit materials and medicines, and must attempt to take action on such practices. As such, the WMA supports the collection and dissemination of data related to assaults on physicians, other health care personnel and medical facilities, by an international body. Assaults against medical personnel must be investigated and those responsible must be brought to justice.

In Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan as well as in many other nations in conflict around the world, the following remedies must be implemented immediately:

1. The establishment of healthcare safe zones in conflict regions to ensure the integrity of hospitals, clinics, and medical centers.

2. Allowing safe and unfettered passage of medical supplies, equipment, and personnel.

3. Cessation of all attacks on patients, pre-hospital personnel, and hospital medical staff.

4. Recognition by all parties of the neutrality of health care workers and their rights and responsibilities to care for any sick and injured patient, regardless of their nationality, race, religion, or political point of view.

The authors are representatives of academic training centers worldwide that provide global health professionals with education and training in humanitarian assistance where every healthcare provider, both civilian and military, is made aware of the inherent protections accorded to them under international law.7 In the same Oslerian spirit of over a century past, we condemn absolutely these deplorable actions in Syria and demand their immediate cessation; and we ask healthcare providers globally to do the same.

Competing Interests

The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’s own and do not reflect the view of their affiliated institutions.

Corresponding Author

Frederick M. Burkle, Jr.: [email protected]

Methods: To achieve this goal, it was undertaken: i) qualitative evaluation to assess the impact of earthquake on services and facilities of the university, the emergency preparedness and the measures adopted to face the emergency, ii) survey on the role played by Student Associations, both in emergency preparedness and response, according to students’ perception; iii) quantitative analysis to measure changes in the enrollment trend after the earthquake, and how university policies could curb students’ migration.

Results: The policies adopted by the University allowed to diminish students’ migration; however, the measures taken by the university were based on an ad hoc plan as no emergency and continuity plans were prepared in advance. Similarly Student Associations got involved more in restoration activities than in emergency preparedness and risk awareness promotion.

Discussion: Greater awareness and involvement are essential at each level (administrators, faculties, students) to plan in advance for an adverse scenario and to make important steps forward in understanding and embracing a culture of safety. The present paper is starting point for future research to deepen the emergency preparedness of Universities and the role that Student Associations may play to support and spread such a culture of safety.

]]>Introduction

At 3:32 a.m. (UTC+1) on 6 April 2009 an earthquake of Mw=6.3 hit the historical downtown of L’Aquila and its hinterland. The mainshock was anticipated by a long lasting seismic cluster (Ml<4.0) that begun in the second half of December 2008. Luckily, two major shakes of Ml=3.9 and Ml=3.5 developed few hours before the April 6th mainshock, alerted the population and induced part of them to flee the buildings and spend the night outside 1,2. The earthquake caused 308 dead, 1500 injured and 63000 displaced. Among the dead, 55 were university students, of which 8 died in the collapse of a university dormitory. Had the earthquake occurred in daytime, the people involved in the collapse of ancient public buildings would have been probably much higher. The high seismic risk in Italy depends not only on the frequency and the intensity of the earthquake hazard, but also on the vulnerability of the built environment. The Italian territory is dotted by many ancient buildings liable to collapse during earthquake 1,2,3,4,5,6. The government agency responsible for promotion and coordination of disaster risk reduction activities in Italy is the Department of Civil Protection (DPC), which was established by Law 225/92, recently amended by Law 100/2012. Other and more specific framework laws (e.g. L.D. 81/2008 8, M.D.10 March 1998 7) define the responsibilities and duties of certain public agencies, including the universities, in terms of emergency planning and risk reduction. In the specific case of public universities, the Law gives to their government bodies (e.g. the chancellor, the academic senate, and the board of directors) a certain degree of autonomy to decide strategies for disaster risk reduction, including the staffing and organization of an internal emergency management group. Indeed, emergency planning beside improving safety and security of students, is a moral obligation of universities, which also safeguards the execution of their institutional scope, namely higher education and professional training activities. The inability to provide basic services like courses, exams, graduation, research, after a disaster, may fatally impact a university reputation and financial status. This becomes particularly important, when the university plays a key role in the economy of the local community. At the time of the earthquake, the University of L’Aquila had 23000 students enrolled across its various graduate and undergraduate degree programs; the student population was almost one third of the total number of residents of L’Aquila 9. Hence, the university was a major source of employment and income for the city and its surroundings, as well as a fundamental drive for cultural and social activities of the city. The negative effects endured by the university bore direct consequences on the city, the inhabitants and particularly the students. In this scenario, the students are not just patrons of the university, but also part of the social fabric of the city; thus, students should be involved in the emergency planning processes of both the city and the university. Such involvement happened only in minimal part in the 2009 earthquake. In Italy, as in many other parts of the World, students take part of the university governance process through the Student Associations. These organizations are directly managed by the students and are dedicated to improve all the aspects of students’ life in higher education. Their scope ranges from safeguarding students’ rights (e.g. welfare and representation) to promote social, political and cultural initiatives. Concurrently, Student Associations are an important interface between the university and the local community, contributing to the civic debates and processes 10,11. The University of L’Aquila was not an exception to this, and four major student organizations were active at the time of the earthquake: the “Azione Universitaria” (rightist political view), “Lista Aperta” (catholic oriented), “Unione degli Universitari” (leftist political view), and “Modus” (non-partisan). All the Srudent Assoctions took part to the University politics with initiatives on the “right to education” and student safety and security. Analyzing the impact of the April 6th 2009 earthquake on the University of L’Aquila both in terms of facilities and business continuity, this study assesses the emergency reparedness and response capability of such university, and the strategies adopted to restore the education activities and avoid students migration to other universities. In addition, emphasis is placed on the role played by Student Associations during pre and post-disaster phases, as well as how the student population perceived the activities performed by these associations.

Emergency management in universities

Over the past years various disasters affected universities and higher education institutions worldwide. For example, Hurricane Katrina’s impacted Tulane and Louisiana State Universities (August 2005). The Midwest seismic event (April 2008). Those events determined economic losses to universities both in terms of structural damages and disruption of academic activities. Indeed, comprehensive pre-disaster planning and preparation can considerably reduce the negative effect of extreme events 12. The US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has financed the Disaster Resistant University (DRU) program, in order to develop planning strategies for vulnerability reduction in american universities 13,14. In Canada, universities are not held directly responsible for emergency management; emergency planning and management is coordinate with local authorities 15. In England, Easthope and Eyre 16 published a manual entitled “Planning for and Managing Emergencies: A Good Practice Guide for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). The authors made a distinction between the emergency planning and the business continuity management. Special attention is dedicated to training, drills and exercises, and emergency communications, with the latter having a key role in the planning processes 16,17. In Italy, the issue of safety and security in Universities was tackled in 2007 by the Italian Universities Chancellors’ Permanent Conference (CRUI), which commissioned a thorough investigation of how emergency management regulations are applied within the public university precincts. The study showed that a vast majority of the Italian universities has developed, within their organizational structure, a Health and Safety Office (HSO) to which are delegated emergency management responsibilities. However, CRUI found that 47.2 % of the universities do not perform emergency planning activities systematically. Therefore, even if the Italian universities started to incorporate safety and security strategies in its official procedures, many steps forward have to be done to turn theory into practice 18. Some hindrances also arise from the Italian law framework on emergency management for universities, which is strictly connected with workplace health and safety 7,8 and it is only focused on the immediate response to minor operational incident (in contained areas or within a classroom or laboratory). The March 10th 1998 Decree of the Italian Ministry of Interiors defines the criteria about the fire control and workplace accident management, drafting evacuation and the fire brigades alarm procedures. As a consequence, disaster prevention or business continuity management is not really contemplated in Italian university, and there is a widespread underestimation of risks by the local emergency managers 18.

University Student Associations and emergency preparedness: a neglected nexus

In spite of the different forms of configuration, management, financing and scope of Student Associations in different parts of the World, a common purpose of these organizations is representing students’ prerogatives to enhance their studying experience (e.g. asking for better school services, curriculum or educational funding). Many Student Associations are nonpartisan, yet such organizations are catalysts of students’ activism and have greatly influenced political debates on both local and global issues. For example, in the United States, France, United Kingdom, and many other countries, the political vehemence of Student Associations reached a high in the 1960s and 1970s during the protests and strikes to end the war in Vietnam and against the invasion of Cambodia 19,20. In the 1980s new subject matters, such as equal opportunities, feminism, environmentalism and humanitarianism, softened the political activism of Student Associations, yielding attention to more local issues of tuition fees or student representation in college governance 21. In Italy most Student Associations have a declared and deep-seated political characterization, and are organized into bodies with a hierarchical structure emulating the country’s political administrative layout. Although the first appearance of organized associations of university students in Italy can be dated back to the 1920, during the Fascist era, it was only after World War II that these associations became truly representative of the whole national students’ community. Indeed, the contestation years of the 1960s and 1970s produced protests and riots activities in Italy too. The ensuing social and civil developments of Italy, weakened the militant components of Italian Student Associations, which by the early 1990s were completely engaged in nonviolent debates. Nowadays, these associations confederated in lists coalescing into three major political views; conservative, catholic-moderate, and liberal-progressive. All these associations operate at the local level electing the “Student Council” which has propositional functions at the Faculty Council, Academic Senate and the University’s Boards of Directors. They also partake into the “National Council of University Students,” a permanent panel which select representative to the “National University Council” (the advisory board of the ministry of education that composed by university’s rectors, faculties, students and employees). Beside these nationwide and chartered Student Associations there exist other, more independent and goal oriented, student organizations. Their scope and inspiring foci can be very different one another, ranging from specific cultural interests, to international student exchange programs, including volunteer services. Unquestionably, Student Associations, in spite of their scope, national vs. local, or their objectives, partisan vs. nonpartisan, are an invaluable resource for the university on a variety of purposes, including students’ safety and security. Yet, this resource is most often completely untapped in terms of disaster prevention and preparedness activities, especially for increasing risk awareness and knowledge transfer. This appear to be true in Italy as well as in many other countries; as a matter of fact, no consistent information about a systematic engagement of Student Associations in disaster risk reduction was found. The potential for this nexus is remarkable, both for developing a culture of safety with younger generations, and for boosting universities’ emergency planning and procedures. Involving students in the campus’ safety and security programs, would increase their awareness of potential hazards and risks in their locale, and train them with protective behaviors and emergency procedures. Gaining students’ attention on such initiatives should not be too challenging, considering the high number of enrollment of students (especially undergraduates) in hazards and disasters related degree programs and courses 22.

Student Associations in L’Aquila