Methods: In this work three methods to detect radioactivity are briefly compared focusing on the most recent, which converts a smartphone into a radiation counter.

Results: The results of a simple sensitivity test are presented showing the measure of the activity of reference sources put at different distances from each sensor.

Discussion: The three methods are discussed in terms of availability, technology, sensitivity, resolution and usefulness. The reported results can be usefully transferred into a radiological emergency scenario and they also offer some interesting implication for our current everyday life, but show that the hardware of the tested smart-phone can detect only high levels of radioactivity. However the technology could be interesting to build a working detection and measurement chain which could start from a diffused and networked first screening before the final high resolution analysis.

]]>Introduction

The number of nuclear plants in the world, either in or out of service, is growing and many of them are built with obsolete technology and are becoming older and older 1. Therefore some release of radionuclides into the environment can be expected in the future.

For this reason, the average (informed) citizen and big organizations could both be interested in innovative and simple methods to check the radiological safety of the local environment and of commodities, starting from foods. Traditional methods require special expertise with expensive and heavy devices and for this reason they are not very popular and only specialized organizations can afford them. On the other hand, if detecting radioactivity were as simple and cheap as measuring atmospheric pressure or body temperature, it could raise a great interest especially in our networked society and particularly during a radiological emergency.

In recent years, an astounding availability of portable and wearable 2 sensors has flooded the consumer market, as an effect of the explosion of the smartphone market.

Almost anyone can currently monitor georeferenced environmental parameters and can find out and share their measurements in real time 3.

The parameters that can be more easily measured by a smartphone and the appropriate apps installed and running are: local magnetic field (Intensity and direction), visible light (intensity and composition in terms of three-component colorimetric measurement), sound (level and spectrum), atmospheric pressure, atmospheric humidity, latitude, longitude, speed, acceleration, local gravity. In the same way it is well known that almost everyone can take and share in real time georeferenced photos, videos and sound recordings.

It is less widely known that with the same hardware (a smartphone with a built-in camera) and the appropriate software, anyone can monitor radioactivity and measure its intensity, although with sensitivity limitations 4,5,6,14.

In this work, three methods for radioactivity detection and measurement in commodities and in the environment are briefly compared and discussed. They are different in technology, sensitivity, resolution, and cost.

A method that is very recent relies on the current smartphone technology, with no need for additional hardware, which makes it cheap and widely available. It could be valuable for a wide screening activity and for the production, spreading and sharing of information 7. The aim of this work is to verify its putative usefulness in the field.

The two other methods are well known in the specialized laboratory and depend on specialized instruments. They were adopted here as a reference to evaluate the usefulness of the method based on the smartphone technology.

Methods

The Reference Sources

To test and calibrate the detectors adopted in this work, a reference standard, characterized by a weak and safe (NRC/IAEA/EU exempt quantity) but clearly detectable gamma ray emission, was needed. A set of eight factory-calibrated point sources was chosen: the RSS8UN set by Spectrum Techniques, LLC., including Ba-133 (t1⁄2 = 10 year), Cd-109 (t1⁄2 = 462.6 day), Co-57 (t1⁄2 = 271 day), Co-60 (t1⁄2 = 5.27 year), Mn-54 (t1⁄2 = 312 day), Na-22 (t1⁄2 = 2.6 year) and Zn-65 (t1⁄2 = 244 day) at 3.7×104 Bq on May 2015, Cd-109 (t1⁄2 = 463 day) and Na-22 (t1⁄2 = 2.6 year) at 3.7×104 Bq on Apr 2015 and Cs-137 (t1⁄2 = 30 year) at 3.7×103 Bq on Apr 2015.

The Instruments

The first kind of detector adopted was based on smartphone technology.

Three common models were tested. They were equipped with a specialized app: “RadioactivityCounter” 4,8 (https://www.hotray-info.de/). The app is available for Android and iOS systems.

The adopted models were Samsung S4, Samsung S7 and Samsung A3.

The S4 is equipped with a 4.4×3.4=15 mm2 sensor (resolution 4128 x 3096 = 12780288 pixel), the S7 is equipped with a 4.2×3.1=13 mm2 sensor (resolution 4032 x 3024=12192768 pixel), the A3 is equipped with a 3.6×2.7=9.7 mm2 sensor (resolution 3264 x 2448 = 7990272 pixels).

CCD or CMOS chips, used as digital image sensors in surveillance or in smartphone cameras, are sensitive not only to visible light but also to higher energy photons. The software analyzes the signals produced by the front or by the rear camera of the smartphone, which has been previously shielded from visible light by an alluminium foil, subtracts the thermal noise and estimates the gamma-ray exposure of the sensor. Furthermore the background emission (measured before) can be subtracted.

The second kind of detector was the Geiger counter PRD 100 (https://www.prd100.com/), made by ITS srl. This device is equipped with a Geiger-Müller tube of 111 mm length x 11 mm diameter (max. section 1221 mm2), which is small enough to allow full portability but whose section is much larger (82 times) than the section of the largest smartphone sensor (15 mm2).

This detector shows additional interesting features: it is cheap (around 100 €), it is small and easily portable (190 g, 123 mm x 91 mm x 35 mm) it works with rechargeable standard batteries (3 AA), it can work in stand-alone mode and/or connected with a smartphone via a Bluetooth radio interface.

A dedicated app (Marie pro PRD-100) running on the smartphone provides some essential real time radiation counting and data displaying, saving, sharing and geo-referencing.

The third kind of instrument chosen in this work was a 1024 channel NaI(Tl) gamma spectrometer made by Ortec, priced around 18000 €.

The system hardware consists of a thallium-doped sodium iodide detector enclosed in a low-background lead shield (30 mm thick), an analog-to-digital converter (ORTEC DigiBase) integrated in an all-in-one spectrometer, and a laptop PC. The digiBASE supplies the multi-channel analyzer function, the high voltage for the NaI(Tl) detector, and all the signal processing electronics. The internal stabilization electronics and the internal check source (K-40 4500 Bq/kg) allow the system to be used over a wide range of environmental conditions. However it can be hardly defined portable, if the 80 kg lead shield is taken into consideration. The NaI(Tl) crystal is a 76.2 mm height x 76.2 mm diameter (3” x 3”) standard. The digiBase is connected to the control computer via a USB interface, which powers the whole system.

Several proprietary software components control the instrument, from the first setting to the final analysis. Ortec MCB Connections-32 acts as a first-level connection driver for the DigiBase. Maestro-32 MCA Emulation Software provides the second-level control of the DigiBase, the live spectral display and the automatic control of acquisition and analysis. This is achieved via a graphical user-programmable interface or via pre-programmed job streams. The software provides also data and results printing and storage. NuclideNavigator is an interactive gamma-ray reference and library program to view, query, and extract gamma-ray energies and yields, half-lives and parent/daughter relations from databases. It can be used to build application libraries or working libraries. ScintiVision-32 is an integrated multi-channel analyzer (MCA) emulator and gamma-spectrum analysis program. It integrates Maestro-32 functions and manages the collection and analysis of gamma-ray spectra. It includes commands that allow you to edit nuclide libraries and automated command sequences or “job streams.”

The set of technologies described regarding gamma-spectroscopy with sodium iodide scintillator allows the identification and quantitative determination of gamma ray emitting radioisotopes, either natural ones such as K-40, U-238, Th-232 or anthropic ones such as Cs-137 and I-131 9, single or in simple mixture 10.

A fourth method must be cited, though it was not experienced in this work, because it represents the state-of-the art in gamma-ray spectroscopy. It is based on High Purity Germanium (HPGe) detectors and can give excellent gamma signal resolution in the whole spectral window, even for energies as low as 3 keV, where NaI(Tl) detectors cannot usefully work and gives a resolution 16 times better than NaI(Tl). The major drawback of germanium detectors is that they must be cooled to liquid nitrogen temperature to produce spectroscopic data. An HPGe system is more complex to manage and on average is priced five to ten times as much as a NaI(Tl) system.

The radon issue

The Radon is a ubiquitous gas, mainly derived from the natural U-238 decay chain.

Radon isotopes emit alpha particles but some radionuclides from Radon’s progeny (Pb-214, Bi-214) emit gamma rays and can add their signals to the spectrum of a sample. To address this problem an independent Radon sensor was adopted to estimate the radon concentration during the analyses by the NaI(Tl) system.

The sensor adopted is the Rstone by Rsens. It can be connected to a computer by a proprietary USB pen. A proprietary program can read and analyze the data stored in the sensor’s memory. The sensor itself runs on a battery whose charge can guarantee up to two weeks of continuous autonomy and monitoring, and has a display to check the current Radon concentration measured during the last 30′.

The Background management

With the “RadioactivityCounter” app running on a smartphone, the sensor noise and the background emission can be measured and stored in the memory, and can be subtracted from each sample measure. Measures are expressed in CPM and saved as total and by-minute counts, together with the sensor temperature (that can affect the measure).

No background compensation is provided by the PRD-100 Geiger counter and by the corresponding Marie PRO PRD-100 app running on a smartphone connected to the instrument. The counting is only instantaneous.

The NaI(Tl) gamma spectroscopy systems allow full control of the background.

The instrument is protected by a lead shield that effectively prevents the variable environmental background radiation from hitting the sensor. The shield itself is a source of radiation mainly from U-238, and Th-232 decay series; anyway this radiation is constant (except for the environmental radon contribution) and can be measured and subtracted with high reliability and precision, acquiring “blank” spectra periodically. The K-40 internal standard can also be included in the background. Therefore a spectrum of the background and of the internal standard was acquired for 963933 s, checking for its stability (on the Energy axis) and saving the result every 1800 s. The stability was assessed by continuously keeping the laboratory temperature as close as possible to 295K and monitoring the stabilizer of the instrument, locked to the K-40 peak: if some adjustment occurred, then the corresponding 1800 s set of data were discarded. This way, the centroid of the photopeak of the K-40 at 1461 keV was always kept corresponding to the channel 552.20+/- 0.20.

The Calibration of the NaI(Tl) system

The spectrum described above, was used either for the background subtraction or for the first calibration step 11 and all the following spectra were acquired with the constraint of the K-40 centroid corresponding to channel 552.20 +/-0.20.

The energy calibration of the NaI(Tl) system was done in several steps. For a first energy calibration the K-40 peak (4518 Bq) was considered with some clearly recognizable peak of the background: the Tl-208 peak at 2614 keV, near the high energy end of the spectral window , from the Th-232 decay chain, which is widely used as a gamma tracer of natural thorium 12,13 and the Bi-214 peak at 1765 keV which is widely used as a gamma tracer of natural uranium 12,13.

During the second step the energy calibration was refined by considering, from the same background spectrum, the Ac-228 peak at 969 keV, the Tl-208 peak at 511 keV and the Pb-212 at 239 keV from the Th-232 decay chain.

For the final energy calibration steps, three reference sources were chosen and their corresponding spectra were acquired: Ba-133 (53 and 81 keV peaks), Cd-109 (88 keV peak) and Cs-137 (662 keV peak). The spectrum of each source was acquired separately, for 66691 s (Ba-133 and K-40), for 14189 s (Cd-109 and K-40) and for 81453 s (Cs-137 and K-40). The three point sources were acquired without any correction for the geometry, at 75mm from the detector surface, to lower the intensity of their signals and make it possible for the stabilizer to work properly.

The final calibration is reported below, where “Channel” is the integer index of the channel ranging from 0 to 1023:

Energy = -7.7883 +2.568091*Channel +0.000165948*Channel2

The full width at half maximum (FWHM) was calibrated as a linear function of energy:

FWHM = 4.8213 +0.038887*Channel

The Efficiency was factory-calibrated.

The test of smartphone sensitivity

The rear (main) camera of each smartphone was shielded from light using a piece of aluminium foil. The “Radiation Counter” app was loaded and launched and the shielding effectiveness was verified by assessing that the background remained unchanged also putting the shielded lens near a strong light lamp. The activity of the Na-22, Zn-65 and Cs-137 sources were measured putting them at 75, 30, 15, 5, 0 mm from the lens’ surface of the rear camera of each smartphone for more than 1200 s.

The Background was checked by putting the radioactive sources at a distance greater than 4m.

The same protocol was followed with the Geiger counter, referring the distances listed above to the instrument surface that directly covered the Geiger-Müller tube.

Results

In the laboratory where the NaI(Tl) spectrometer works and where the radiation counters were tested, the radon concentration varied between 20 and 60 Bq/m3 during the testing periods and at this level did not require any special attention. The main environmental problem was to keep the temperature stable to have the NaI(Tl) spectrometer stable as well.

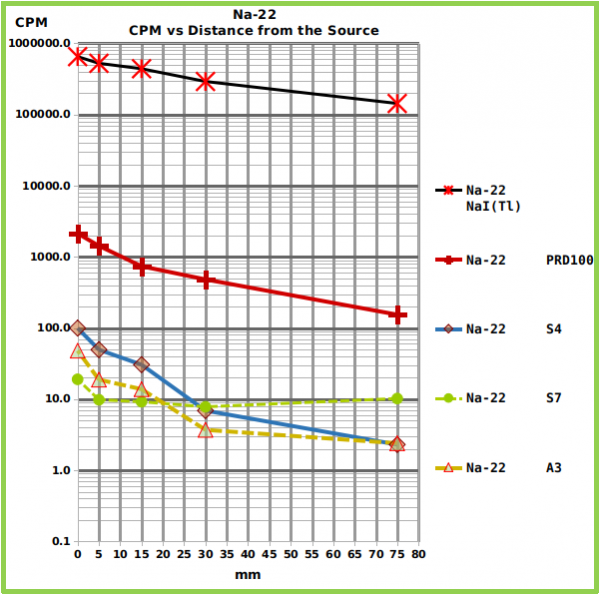

Only the strongest radioactive reference source (Na-22) could induce a response that was clearly different from the background in all the counters, smartphones included, as reported in Fig. 1 and in Tab. 1. Figure 1 and Table 1 show graphically (Fig 1) and in tabular format (Tab. 1) the measures obtained from each counter, at different distances from the Na-22 reference source.

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the four tested radiation counters and of the NaI(Tl) spectrometer, put at different distances from Na-22 reference source of gamma rays. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1.

Fig. 1: Graph showing the relationship between counts and distance, for each counter, from the Na-22 reference source.

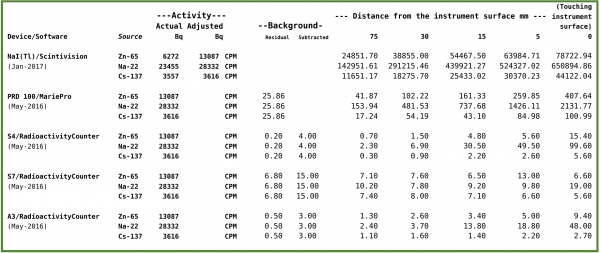

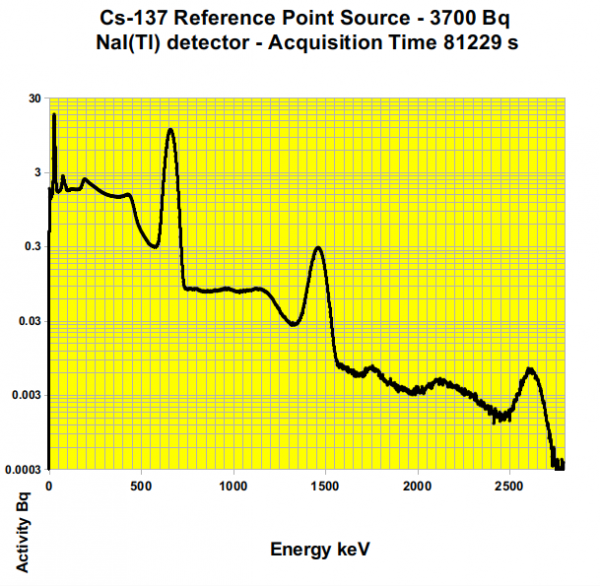

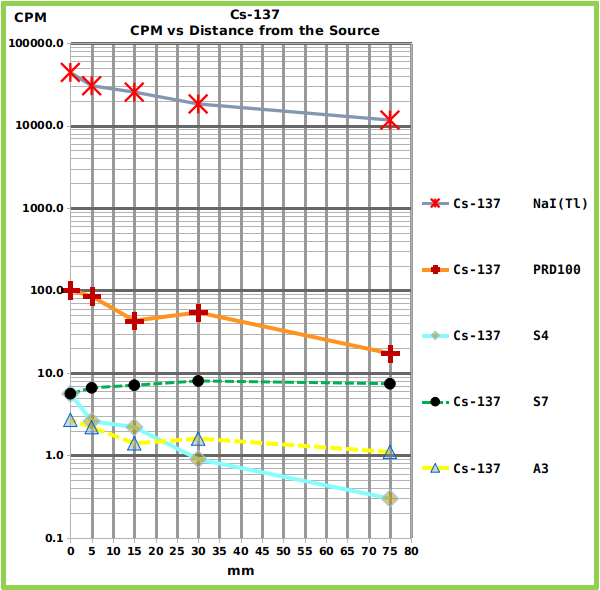

Table 1: The Table shows the output, expressed in CPM (Counts Per Minute) of the tested radiation counters and of the tested NaI(Tl) spectrometer, put at different distances from three different reference sources of gamma rays. For the NaI(Tl) spectrometer, the counts from the whole spectral windows were considered and the output adjusted for the half-life of the nuclides and for the different acquisition date.

The NaI(Tl) sensor showed a very different sensitivity.

For the sake of comparison, the photo-peak of the reference source of Cs-137 (3700 Bq), put on the surface of the NaI(Tl) sensor (18200 mm2) gave a count of 1.31*104 CPM and was “viewed” by the spectrometer as a 1L sample containing 7262 Bq/kg of Cs-137 (Fig. 2). This kind of instrument easily recognizes contents as low as the Tl-208 of the background, “viewed” as a concentration of 19.4 Bq/kg and whose photo-peak area corresponds to 6.60*10-2 CPM (Fig. 2).

Output of the NaI(Tl) Gamma-ray spectrometer. The point source of Cs-137 (t1⁄2 = 30 year, 3.7×103 Bq on Apr 2015, photo-peak 662 keV) was placed on the sensor surface. Also the photo-peaks at 2614 keV (Tl-208 from the Lead shield) and at 1461 keV (K-40 internal standard) can be clearly observed.

Fig. 2: Gamma-ray spectrum of the Cs-137 reference source

The same reference source of Cs-137 (Fig 3 and Tab. 1) was not sensed by the S7 and was hardly sensed by the A3 and only within a distance equal or less than 5 mm. Only the S4 performed reliably.

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the four tested radiation counters and of the NaI(Tl) spectrometer, placed at different distances from Cs-137 reference source of gamma rays. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1.

Fig. 3: Graph showing the relationship between counts and distance, for each counter, from the Cs-137 reference source.

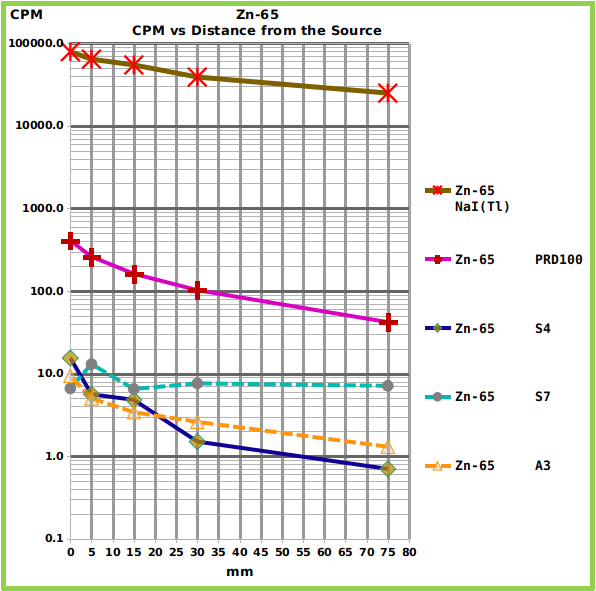

The Zn-65 reference source (Fig. 4 and Tab. 1) showed intermediate counts between the strongest (Na-22) and the weakest source (Cs-137).

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the four tested radiation counters and of the NaI(Tl) spectrometer, placed at different distances from Zn-65 reference source of gamma rays. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1.

Fig. 4: Graph showing the relationship between counts and distance, for each counter, from the Zn-65 reference source.

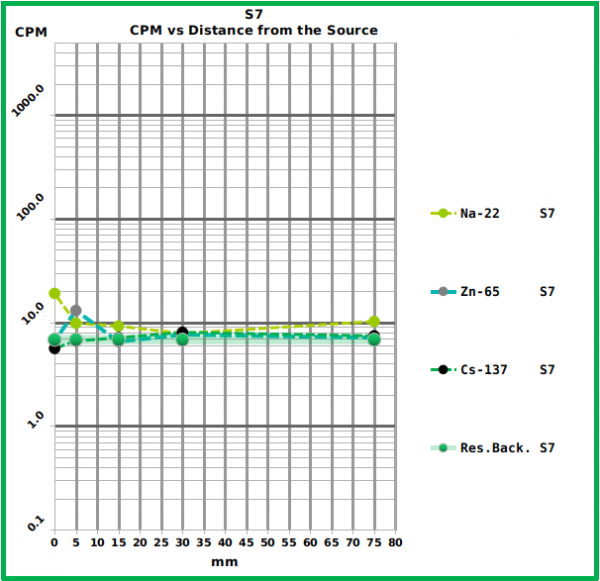

The three smartphones performed very differently. The most recent one (Samsung S7), which is equipped with the most advanced (and small) sensor showed too much background thermal noise and was not able to sense the reference sources (Fig. 5 and Tab. 1) , except for the strongest (Na-22) at the minimum distance. On the other hand, only the S7, running under Android 6 (the A3 and the S4 runs under Android 5) showed no problem with file saving.

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the three tested radiation sources placed at different distances from the S7 surface. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1. The residual background level is also reported.

Fig. 5: Graph showing the response of the S7 smartphone to the different reference sources at the different distances.

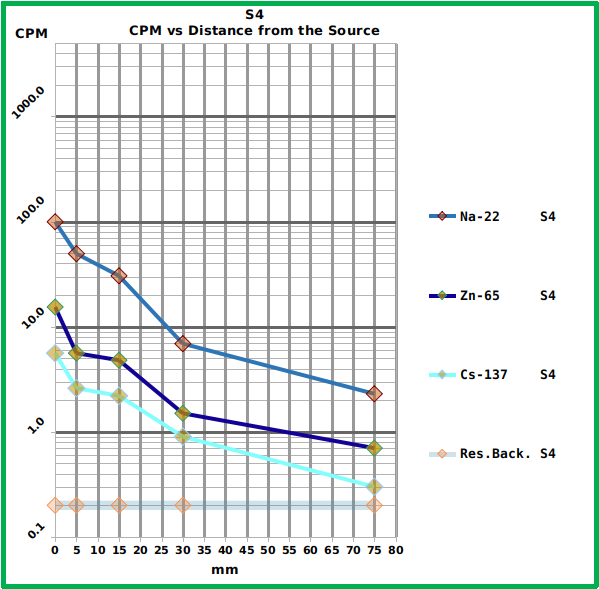

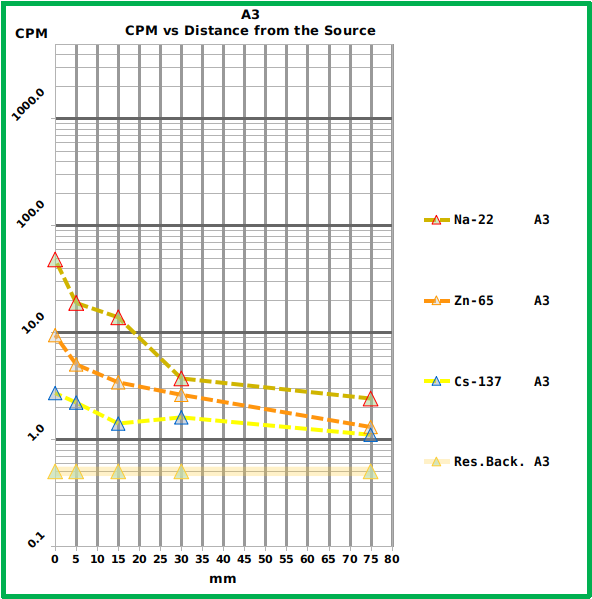

Among the tested smartphones the most reliable was the S4 which showed a good sensitivity and whose counts followed the expected trend (Fig. 6 and Tab. 1). The A3 showed less sensitivity and performed worse (Fig. 7 and Tab. 1).

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the three tested radiation sources placed at different distances from the S4 surface. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1. The residual background level is also reported.

Fig. 6: Graph showing the response of the S4 smartphone to the different reference sources at the different distances.

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the three tested radiation sources placed at different distances from the A3 surface. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1. The residual background level is also reported.

Fig. 7: Graph showing the response of the A3 smartphone to the different reference sources at the different distances.

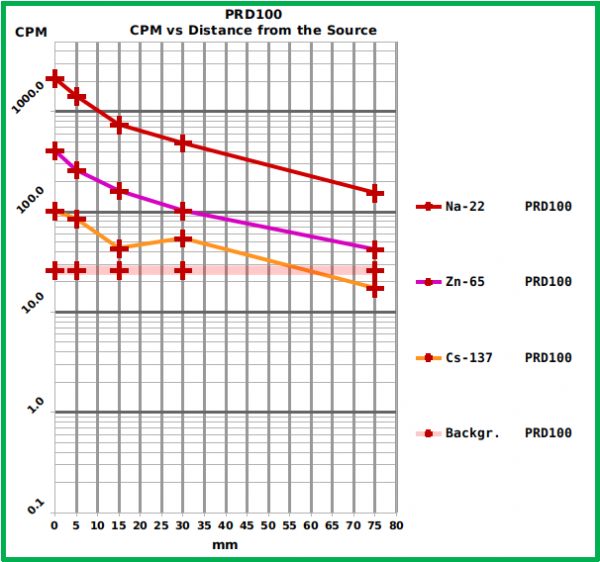

The Geiger counter PRD100 (Fig. 8 and Tab. 1) showed a much higher (one order of magnitude) sensitivity of the best performing smartphone (S4) but the software running on the connected smartphone lacks some useful feature which is present in the “RadiationCounter” app. (that is to say data-saving in CSV standard format, a count every 60 s, temperature and battery status and, for each measuring session, total duration, background, noise related to the border of the sensor). Furthermore the app allows real-time background subtraction, 60 s to 1800 s means and general mean calculation.

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the three tested radiation sources placed at different distances from the PRD100 surface. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1. The residual background level is also reported.

Fig. 8: Graph showing the response of the PRD100 Geiger counter to the different reference sources at the different distances.

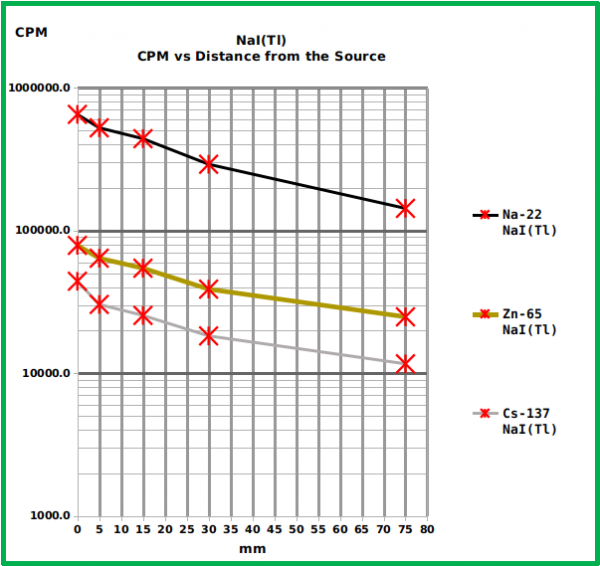

The NaI(Tl) spectrometer showed (as expected) the best sensitivity (Fig. 9 and Tab. 1) and the highest reliability with the best background management.

The Graph shows the Counts Per Minute (CPM) of the three tested radiation sources put at different distances from the surface of the sensor of the NaI(Tl) gamma spectrometer. The total counts from the whole spectral window are considered to allow a proper comparison with the other devices. The numerical values are reported in Tab. 1. The background is not reported here because it depends on the K-40 internal standard and on the lead shield, not on the external environment and it can be evaluated observing the spectrum reported in Fig. 2.

Fig. 9: Graph showing the response of the NaI(Tl) spectrometer to the different reference sources at the different distances.

Discussion

The current smartphone technology could open up to a massive radiation monitoring, with some limitations due to low sensitivity, where the number of data could compensate for the possible lack of precision and puts in the hands of the average citizen a direct knowledge that previously only specialized entities could access.

Furthermore, the fact that anyone can check for the safety of the nearby environment leads to a new kind of bottom-up control of the information released by interested stake-holders and by the public authorities, allowing more transparent decision making.

According to the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) the worldwide average natural dose to humans is about 2.4 mSv/y (millisievert per year) 15.

On the other hand, the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) recommends effective dose limits to reduce the risk of stochastic effects to tolerable levels 16 for members of the general public in planned exposure situations and proposes as first reference level 1 mSv/y. The Commission considers also existing exposure situations that are defined as “those that already exist when a decision on control has to be taken” and explains that “there are many types of existing exposure situations that may cause exposures high enough to warrant radiological protective actions, or at least their consideration”. The Commission proposes the reference interval between 1 and 20 mSv/y for these conditions that can be due to NORM (Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material), natural background radiation and radioactive residues within the human habitat. The Commission defines also the levels between 20 mSv/y to 100 mSv/y as “reference levels for the highest planned residual doses in emergency situations”. Therefore according to UNSCEAR and ICRP, an annual dose ten times the “worldwide average natural dose to humans” is already an emergency.

According to our data, at least one of the tested smartphone (S4) is able to reliably distinguish between a residual background of 0.2 CPM and a tenfold greater gamma emission (Tab. 1 and Fig. 6). The cited background can be assumed to be near the average value, according to UNSCEAR’s definition and according to the information available on the geographic area where the tests were done: the alluvial plain of Florence-Prato-Pistoia 17,18. Therefore, in such conditions, the device could be used to detect an environmental radiation level that could signal a radiological emergency, according to ICRP’s definition 16. On the other hand, no real-time detection can be expected in low exposure conditions because to achieve the reported results, several minutes were needed for each measure and all the measured counts, except the S4 measure of the Na-22 put directly on the smartphone surface (99.6 CPM) are less than one count per second. If we consider that one count per second is equal to 60 CPM that in turn, in this case, corresponds to 300 times the residual background, then it can be concluded that only high levels of gamma activity can be detected in real-time by this kind of device and that the low sensitivity of the small sensor of a smartphone can be a serious drawback, that could be compensated only by the adoption of an external sensor. The low sensitivity would not be a problem in a severe radiological emergency, where the usefulness of many working detectors should be unquestionable and where almost everybody could become an active node in an environmental sensory network. In this scenario the value of the information collected can only be imagined.

Of course the huge amount of environmental data that could be produced and shared needs some public revision and lab validation, and here a sensitive, traditional and inexpensive technology like the NaI(Tl) spectrometry can have a new role, before the definite Hi-Res confirmation that only the HPGe technology can give.

Corresponding Author

Stefano Alessandri, Department of Statistics, Computer Science, Applications “Giuseppe Parenti”, University of Florence, Florence, Italy. Email: [email protected]

Data Availability

The data are freely available in figshare repository and can be accessed via the following links:

– Summary of smartphones, geiger counter and NaI(Tl) spectrometer dataset: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4555507.v1

– NaI(Tl) raw dataset: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4644997.v1

Competing Interests

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Objectives: This study was done to explain the life process of children who survived the earthquake of Manjil in northern side of Iran.

Methods: This qualitative study is based on the grounded theory approach. The sampling involved purposive interviews with 12 children who survived the Manjil earthquake and were under 12 years of age at the time of the earthquake. The initial interviews were followed by continuous comparative analysis, and thus the sampling process adopted a theoretical trend. In the end, by the formation of categories and the central variable of the study, interviews were conducted with 16 subjects and sufficient data was provided. Data was collected through face-to-face, in-depth interviews using an interview guide. In order to enrich the categories formed in data analysis, we had also 6 telephone interviews with the same participants in order to complete missed needed information. Data collection began in 2015 and continued up until 2016. Data was analysed using the Strauss-Corbin approach.

Results: The life process of children earthquake survivors consists of ‘unexpected encounter’, ‘transient relief activities’ and ‘long-lasting consequences’. The central variable of this study is ‘the dark shadow of pain and the light shadow of life expectancy’. The life experience of this group of children is immersed in painful memories and varies under different conditions.

Discussion and Conclusion: According to the results of this study, one of the factors affecting the lives of children earthquake survivors which could threaten their health is providing non-specific and transient services. Training relief staff to consider the specific needs of these children at the time of the rescue operation could contribute to improving their health level in various aspects. Considering the effective and comprehensive rehabilitation program in Disaster Management by policymakers can prevent permanent complications caused by earthquakes. Planning and taking action to identify misbehaviours in this group of children as well as raising public awareness, particularly for parents, on how to manage the outcomes of natural disasters are some of the most significant public health priorities. Providing public mental health services for parents and children who survive an earthquake helps to address potential psychological problems in this group of survivors.

]]>Background

The Manjil earthquake1 occurred on June 21, 1990 at 21 GMT near the town of Rudbar, in villages of Gilan Province and the northwest region of Zanjan Province, Tarom Olya located in the north-west of Iran. The Manjil earthquake caused great human and financial losses within a 100-kilometer radius of the epicentre. The earthquake occurred in Rudbar and Manjil was one of the largest and most destructive earthquakes in Iran in recent decades. The earthquake caused nearly 35,000 deaths and 60,000 injuries, and left more than 500,000 people homeless. In addition, 200,000 residential units were demolished, 60,000 of which were completely destroyed. Due to the landslides that occurred during the Manjil earthquake, villages were deeply buried. The initial damage caused by the Manjil earthquake was estimated to amount to more than 800 billion rials, and the disaster caused economic losses equal to 2.5 percent of the gross national product2.

Introduction

Published statistics of disasters around the world show that in the past two decades, more than 4.3 million people have died, millions of people have been injured and tens of billions of dollars have been spent on financial and life compensations due to natural disasters3. Due to the climatic and geographical situation of Iran, it is one the high-risk countries in terms of natural disasters4. Advances in emergency and injury care systems have caused survivors of natural disasters need wide physical, psychological and social recoveries5.

Among the survivors of the earthquakes, children are more vulnerable than other age groups due to the fact that they are exposed to distressing scenes of devastation. In addition, children survivors are especially vulnerable as their living situations immensely shift following an earthquake disaster. If the special needs of these victims do not receive urgent attention, the evolutionary process of their growth will undoubtedly be interrupted, and they will face serious physical and psychological effects in the near or distant future. Most planning programs emphasise the most immediate needs of disaster victims, including rescue and relief activities and primary care6.

However, it should be noted that in addition to the significant effects and damages associated with natural disasters, the impact of such disasters on victims’ quality of life is much deeper and severe. Therefore, it is crucial to improve the health of victims for prolonged periods after the disaster. Nevertheless, many of the studies conducted in this field have not taken a comprehensive look at this process, and have usually focused on only one aspect such as psychological interventions after disasters, post-disaster stress disorders7,8, physical injuries9, and the role of community participation in physical reconstruction10. Since few studies have specifically explained the lives of children who have survived natural disasters, this study seeks to investigate this particular group. Further, studying children survivors in this context is necessary due to the particular context and culture of Iranian society as it differs from other countries which is based on Islamic beliefs and traditional-local customs. Understanding the life process of these children may lead to effective outcomes and interventions, and explaining the life process of these children according to their experiences could lead to a better understanding of their needs, challenges, issues and problems following their experiences of natural disasters. Furthermore, such a study may reveal the challenges resulting from earthquakes, and may also provide results that are applicable to similar circumstances. Therefore, to address this gap in research, this study aims to explain the life process of children who have survived earthquakes.

Methods

This study was conducted using the grounded theory approach, a qualitative research method based on symbolic interactionism. This study examines the social processes in the context of human interactions11.

The sampling involved purposive interviews with 12 children who survived the Manjil earthquake and were under 12 years old at the time of the earthquake. The initial interviews were followed by continuous comparative analysis, and the sampling process therefore took a theoretical trend. Based on the formation of categories and the central variable of the study, interviews were conducted with 16 subjects, and sufficient data for ensuring about the data saturation was provided as a result. Data was collected through face-to-face, in-depth interviews using an interview guide In order to enrich the categories formed in data analysis, we had also 6 telephone interviews with the same participants in order to complete missed needed information. The interviews began with general questions and progressively involved more detailed questions regarding participants’ responsiveness. Questions included, ‘Can you tell me about your experiences after the earthquake?’ and ‘How was your life?’ Interviews were performed in a quiet atmosphere according to participants’ preferences, in locations such as their homes or in a park. According to the tolerance, willingness and environmental factors of participants, 22 interviews were conducted for this study. The duration of face-to-face interviews was 25 to 45 minutes, and telephone interviews lasted 15 to 20 minutes. Data collection started in 2015 and continued up to 2016.

Data Analysis

Data was analysed using the Strauss-Corbin approach11. According to this method, the current study respectively employed concept analysis (immediately after the first interview), context analysis, process analysis, and then combined and integrated the categories and proposed the basic theory (writing analytical stories and reviewing the reminders). The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed, and the typed texts were reviewed several times. Then, the texts were studied line-by-line and word-by-word, and a code was assigned to each key word or sentence. Similar codes were then put together in a category, and the primary classification of 598 codes was obtained. Constant comparison was used to determine the relationship between categories and search the underlying process of data. Then, the researcher integrated the categories using various diagrams to identify the central variable.

Trustworthiness

The authenticity of the data was examined using the four criteria of Guba and Lincoln12. The data collection took nine months using a combination of face-to-face interviews and telephone interviews. Results were confirmed through peer check and member check. Researchers contributed to the transferability of the data through in-depth descriptions and analysis. The sampling technique with maximum variation (the age at the time of the disaster, gender, losing parents in the disaster, occupation, education level and marital status) was also used, and this improved the suitability or transferability of findings. The researcher precisely recorded and reported on the research process to allow others to investigate the article.

Ethical Consideration

Permission for the study was obtained from the ethics committee of the University Of Medical Sciences Of Babol. Related departments were informed of the study objectives, and their written consent to participate in the study was obtained. The time and place of the interview was determined with the agreement of participants, who were assured of the confidentiality of all personal information and interviews as well as the anonymity of all documents related to the research. The results of the study were made available to the participants upon request. All moral standards relating to the use and publication of texts was observed. Permission to record participants’ voices was obtained. Only one of the researchers listened to the recordings. The recorded interviews did not include any personal identification information. Participants were informed that they could withdraw their information or remove themselves from the study altogether at any time.

Results

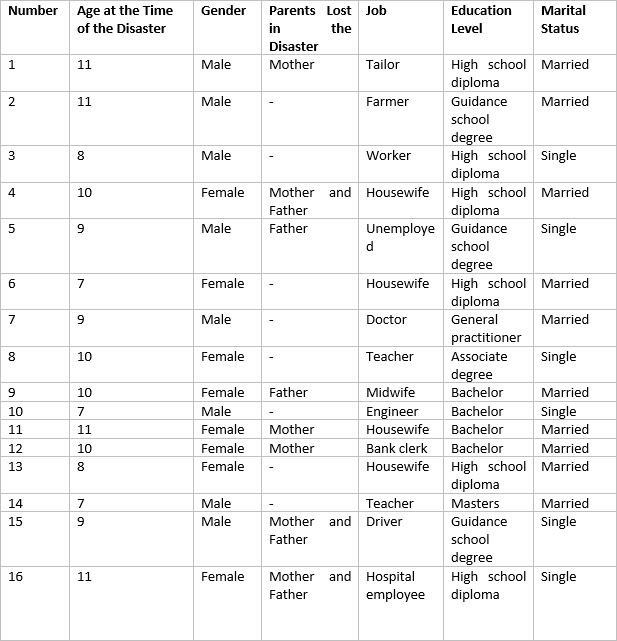

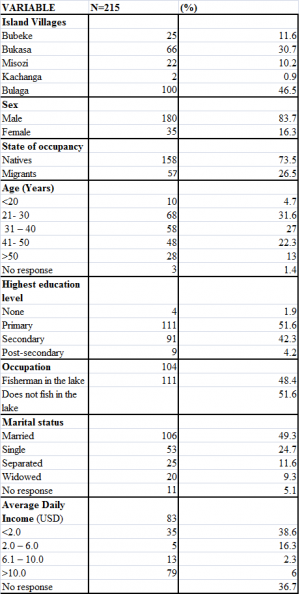

In this study, 16 individuals (adults at the time of the study) who were child survivors of the Manjil earthquake were interviewed (Table 1).

Table 1. Participants’ personal information

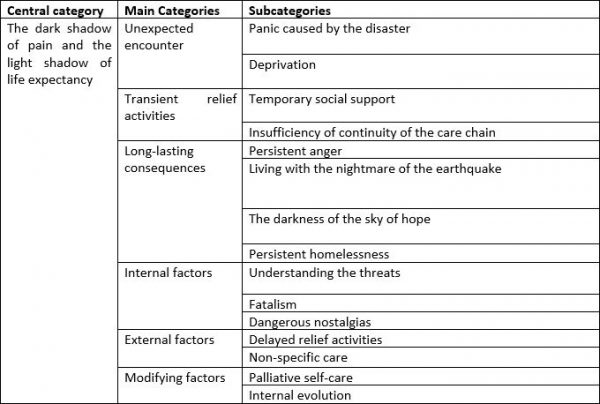

Analysis of the data resulted in the obtainment of 598 primary codes. During the process of data analysis, six main categories were extracted.

The life process of children survived earthquakes consists of ‘unexpected encounter’, ‘transient relief activities’ and ‘long-lasting consequences’. The central variable of this study is ‘the dark shadow of pain and the light shadow of life expectancy’. This process is influenced by ‘internal factors’ and ‘modifying factors’ (Table 2).

Table 2. Categories extracted from the data

Unexpected Encounter

Most of these children were sleeping at the time of the earthquake. Therefore, the fact that they did not anticipate the earthquake or its consequences is associated with reactions of panic and feelings of deprivation.

Panic Caused by the Disaster

The first hours after the earthquake were associated with a great deal of fear, apprehension and horror for the majority of these children. These feelings multiplied when they were exposed to the resulting devastation, such as the destruction of shelters and scenes of family members being buried under the rubble, as well as being exposed to wounded and dead victims.

“The ongoing conditions were like the Resurrection. Destroyed and burnt houses, cracked roads, blood, broken bones, dead bodies along the road etc. Everything was a proof of the Resurrection. I was terrified when my uncle was burying his sister, nieces, nephews and other relatives.” (Code 16)

Deprivation

The deep influences of the disaster appeared a few days after the shock and horror of the earthquake. Most children either lost their parents, or their parents were mourning for the loss of their children or other family members. What were previously conceived of as the neighbourhood, kindergarten, school, family and relatives were no longer present. There was no sign of love or loving atmosphere in the family. Most family members were looking for a piece of bread to eat and shelter to live in, and were struggling with many mental pressures. Sometimes the needs of these children were forgotten due to the disastrous situation. Most of these children had no place to sleep and were looking for a clue of memories of good old days in the ruins. Those who had lost their parents and family members wandered around the ruins and cried, and were in search of a safe haven in a world of fear and helplessness. These children were tired, hungry and looking for a way out.

“The earthquake is nothing but the death of love. All my relatives were buried in front of my eyes, the sky of hope was dark and the pain of this separation grew bigger, and as I grew up, it grew up, too.” (Code 14)

Loneliness and the lack of social security in the initial chaos after the earthquake exposed children survivors to mistreatment. This group of survivors trusted people who were available in the tense and cluttered atmosphere, and exposed themselves to mistreatment. On the other hand, these children were neglected or mistreated due to the preoccupation of police, aid workers and family members who were involved in removing corpses and victims from under the rubble. In addition, some children faced threats such as robbery or getting lost in the process of being delivered to the authorities.

“I was crying in a street among the ruins in that confusion, and I saw a man coming towards me. He told me that he came to take me to my mother. As soon as he saw nobody was noticing, he took my bangle by force in such a way that my hand was wounded, he put his hand on my mouth so that I wouldn’t be able to shout and he threatened me.” (Code 13)

Transient Relief Activities

After some time and immediate support efforts, relief activities were provided to enable reconstruction and rehabilitation. However, these steps involved rebuilding houses and buildings, while the important principle of reviving the lives of these children faded out. This category contains the two subcategories of ‘temporary social support’ and ‘ insufficiency of continuity of the care chain’.

Temporary Social Support

What appears in the early hours following a disaster is the influx of government and relief aids to disaster-stricken areas. However, after a short period of time, emotions subside and the amount of aid decreases. This especially diminishes significantly as time goes on. In fact, disaster activities are only vaguely recalled.

“There were lots of people and aids during the first days. But very soon, after one month everything was over. It was [as though] as if the earthquake had involved people only for those days.” (Code 15)

The concept of ‘forgotten’ refers to temporary social support. Although these children require compassionate care, most of them receive humanitarian support for just a few months following a disaster and are gradually deprived of loving attention.

“Children who have survived earthquakes are highly vulnerable and can be emotionally injured by the smallest issues. They need love and a safe shelter more than anything else.” (Code 12)

Insufficiency of Continuity of the Care Chain

A few months after a disaster occurs, continuous care is halted and survivors face serious physical and mental consequences related to the event. The majority of physical and mental health care is limited to emergency and acute care, and rehabilitation services are omitted. The majority of children deal with several complications due to a lack of long-term care services management and planning. ‘Discontinuous follow-ups’ have caused most survivors to suffer from multiple chronic physical and mental problems.

“I was wounded when the earthquake occurred. My leg was stuck under the ruins of the house and was injured. They took me to the hospital and I was taken care of there, but after that they took me home. My parents couldn’t afford to spend money for me. Unfortunately, I limp. If somebody cared about us then and thought [about] what would happen next, I wouldn’t be like this.” (Code 18)

Long-lasting Consequences

Consequences of earthquakes are often delayed and persistent. This category consists of subcategories including ‘persistent anger’, ‘living in the nightmare of the earthquake’, ‘darkness of the sky of hope’ and ‘persistent homelessness’. The consequences of the earthquake proved to be of lower intensity for children who did not lose their parents in the earthquake and could benefit from their physical and mental protection.

Persistent anger

After the earthquake, the games and carelessness of childhood shift toward adult behaviours. ‘The repetitive scenario of the earthquake’ replaces game-playing and living a happy life. Teenagers also experience a shift in perception as they too experience undesirable physical, economic and social conditions. The majority of children survivors cannot enjoy their childhood years as their welfare, physical condition and psychological capacity are lacking in the wake of a disaster. Therefore, this group of survivors refers to their adolescence as ‘unloaded clusters’ The continuous use of wording such as ‘sorrowful dialogues’ or ‘tragedies’ describe the significance of sad memories of the past experienced in their minds and souls. Their spirit is obscured by these dialogues, and these survivors live with the daily repetition of parts of their painful past and memories of the earthquake. Further, these survivors attempt to pay homage to their family members, classmates and friends by keeping their memorabilia. In other words, they consider forgetting the event as a source of guilt and disloyalty.

“At the time I should have been supported by my family, I was taken to an orphanage. As I grew up, I had to leave my friends and move to another place. These changes made me suffer. I didn’t understand how my teenage years passed.” (Code 4)

Living in the Nightmare of the Earthquake

One of the long-lasting and negative consequences for this group is living in the nightmare of the earthquake. The fear of the earthquake’s recurrence along with continuous insecurity and anxiety are always present. Most of these survivors are deprived of a normal life. Participants expressed that they live in fear not just of the earthquake’s recurrence, but also of other disasters occurring. This fear leads them to experience anxiety. Living with prolonged and continuous anxiety leads to conditions such as depression, psychiatric disorders such as drug abuse, and behavioural problems such as delinquency. Living in the nightmare of the earthquake causes ‘excessive sensitivity’ to others, especially family members. Such behaviours of risk aversion cause these people to draw on their memories of the earthquake and, as a result, deter family members from what they perceive to be possible hazards. This problem is associated with fear, and limits the social lives of victims and their family members. In turn, this brings about dysfunction in the relationships between victims and their family members.

“I’ve grown up and aged, but you know, I start shaking even when it’s windy. I go and sit in a corner of the room, hug my baby and get terrified. That fear is still with me.” (Code 11)

The Feeling of Hopelessness

Some of these survivors believe that the feelings of safety and health have disappeared in their lives and have been substituted by fear, uncertainty and loneliness. They reported that after the earthquake, they feel they have lost their direction in life and have lost all hope. They experience a life without financial and emotional support. Their lives have undergone many major changes, and the grief of losing family members and experience of permanent fear have replaced their normal routine of life. Those who have medical problems and severe physical complications caused by the earthquake are exposed to constant medical procedures and treatment recommendations.

“I was young at that time. Our financial situation wasn’t so bad. But suddenly, we lost everything. My father died hopelessly after a few years. I had to work in a factory. It was very hard. I had to work instead of study.” (Code 13)

The ‘guilt’ the respondents feel as the sole survivor, as well as the guilt associated with burying their loved ones, is a significant factor contributing to their feelings of despair. Most of them saw their family members stuck under the rubble and reported that they feel guilty because they could not rescue them.

“I suffered for a long time. I wished it wasn’t me but my parents who were alive. I was little and injured then. I was confused and frightened, and I couldn’t do anything for my family. It hurts me a lot.” (Code 4)

For this group of survivors, disappointment leads to a lack of desire and effort in social activities. Thus, they always feel that they are a ‘social burden’. Lack of adequate physical and academic qualifications for acquiring a job affects this process. Most of these individuals are not married and live with their relatives because they have lost their families. This problem enables the formation of the feeling of being a social burden.

“I went my uncle’s house in another city. That poor man had some children and didn’t have a good financial situation. He was a farmer. I was a burden to their family. I sometimes realised that they couldn’t help doing favours for me, but I also understood that they couldn’t afford to provide for their own children.” (Code 16)

Disappointment causes this group of survivors to refer to their current life situation as ‘bubbles on the water’ (they always think that everything is temporary and is not going to last long like a bubble), and keeps them from envisioning a future for themselves. They feel abandoned because their identity has been buried under the rubble of grief and misery. The missing future is represented in impairment, inability to support family expenses, lack of financial resources for marriage, losing parents and their emotional and financial support. In fact, these individuals believe that they feel they are not in control of their destiny or have failed to fulfill their destinies. The fear of a life without financial resources and family support is always with them.

“A long time ago, I realised that I lost everything in the earthquake. I have neither a good job nor money. I try more and more, but I am always on the first step.” (Code 2)

Persistent Homelessness

A few days after the earthquake, some children who lost their parents and did not have anybody to claim them were taken to children care centres. In their opinion, wandering in these centres and waiting to find a safe haven was the worst experience of their lives. They described the separation from family members, relatives, friends and their hometown in a very bitter manner. Some survivors were given to new families and thus faced many new problems. Orphans who were sent to welfare centres or new families grew up in educational systems that differed from their native culture. Sometimes, this way of life proved contrary to these survivors’ previous beliefs and life experiences, and thus led to behavioural and mood disorders. According to survivors, sympathy was the major factor in their acceptance to these new families or centres. However, over time, many children survivors once again experienced homelessness due to behavioural disorders and adversities.

On the other hand, the lack of necessary physical and mental conditions for adoption led some of these children to stay in care centres for a long time. Further, such conditions at times caused them to wander between different centres as they grew older or their physical or mental complications increased. Children without guardians were taken to welfare centres. There was also a significant difference between genders in child adoption such that most boys were adopted in a short time while girls spent a long time on the waiting list.

“I stayed in the nursery for a long time. Those who were with me were adopted by their relatives or new families. I was sick, I think that’s the reason.” (Code 15)

An important point revealed through data analysis was that some of the parents of children survivors were noted as ‘risky parents’. These parents pose risk factors in the physical, mental, moral and social development of their children due to the loss of their own parents or other children, or due to multiple physical injuries caused by the earthquake. These people cannot provide a safe haven for their children to live. Escape, isolation, and anxiety are just some of the outcomes and emotional experiences of children living with risky parents.

“At first, my father was too nervous because he had lost all his money and two of his brothers in the earthquake. He was usually bad-tempered to me. I remember that he hit me and my mother for small excuses. I grew up in that difficult situation and its result was that I couldn’t study at school. I always started fights at school. Now I am unemployed.” (Code 5)

Internal Factors

The internal factors affecting the life process of children who survived the earthquake are ‘understanding threats’, ‘fatalism’ and ‘dangerous nostalgias’.

Understanding Threats

For children earthquake survivors, facing stressful events, experiencing failures in family and social life, and emotional and educational breakdowns over the course of their lives cause them to feel threatened. The intensity of the feeling of threat shifts according to the context of each individual’s condition. Thus, the intensity and type of stressors influence the intensity of the feeling of being threatened. Feeling threatened affects these survivors’ performance in rebuilding their lives after the earthquake.

“I feel so impatient. Once I was supposed to marry a girl but she left me, I experienced a feeling exactly like which I experienced at the time of earthquake. I reviewed all of my miseries. I felt lonely and threatened very much. I was depressed and devastated for some days.” (Code 15)

Fatalism

Believing in fate and luck are personal factors affecting the life process of these children. According to participants, feeling unlucky suppresses the opportunity to build personal, family and social dimensions of life. It can also cause depression, isolation and social isolation.

“If I was lucky, why should I have been so miserable from childhood? Whatever I do, my bad luck and a part which has been already written in my destiny is with me.” (Code 5)

Dangerous Nostalgias

Internal factors which affect the life process of these survivors include breaks in time and retrieving memories of the earthquake when facing similar scenes or events.

“One day, a motorbike had an accident with a car in the street. The motorbike rider’s leg was stuck under the car’s tire. As I saw this scene, I remembered my mum, her leg was stuck under the rubble of our house. The motorbike rider’s shouts reminded me of stressful scenes and my mum’s shouts. I felt so bad. I cried for many days.” (Code 13)

External Factors

‘Delayed relief activities’ and ‘non-specific care’ are external factors which affect the life process of children who survived the Manjil earthquake.

Delayed Relief Activities

A remarkable finding in the data is that often, treatment measures are delayed due to children’s inability in expressing their immediate needs. This problem is worse in children with injured parents or for those who have lost their parents. Parents help aid groups in considering their children’s needs with the knowledge they have about their psychological characteristics or physical problems. Delayed diagnosis or treatment of different problems of these survivors could have serious and persistent consequences for them.

“I was there when they took a 7-year-old child to the hospital. The child cried and couldn’t answer them when they asked questions. Nurses didn’t even know what medicine the child was allergic to. I remember the doctor gave the child a medicine. The poor child was shocked immediately and died, and it was too painful for me. If they hadn’t given the drug, the child wouldn’t have been dead.” (Code 10)

Non-Specific Care

Health care is not often provided to alleviate the physical and mental needs of children who have survived an earthquake. This reduces the quantity and quality of services. Most attention is focused on mere physical needs, and the mental and emotional needs of these children are neglected. In the area of physical health care, aid workers forget some children, or at times offer them defective or delayed care due to their lack of knowledge of specific care for children.

“They took me to the hospital. I heard two doctors saying that if the aid workers had paid more attention or been trained, they wouldn’t have cut a woman’s leg who was on a bed next to me.” (Code 5)

Modifying Factors

‘Palliative self-care’ and ‘Internal evolution’ are modifying factors in the life process of children who survived the earthquake.

Palliative Self-Care

The lack of long-term social and family services leads to self-action to have a safe and normal social and family life. Children seek different strategies to rebuild various aspects of their lives during different life stages. This category consists of three subcategories including ‘rescue efforts’, ‘religious strategies’ and ‘resilience’.

Rescue Effort

The development of social communications, starting a family, having children and maintaining emotional ties are some of the strategies used by children in rebuilding their lives after earthquake. On the other hand, being optimistic in life, strengthening the ability of forgiveness, being involved in charity works, and public participation have calmed these people. According to participants, empathy is formed in peer groups because of their common pain. By developing social relationships, these people look for those who can be understood easily by them due to the common experience they share. Sharing memories of childhood and using coping strategies proposed in these groups improves their mental relaxation.

“At the moment, I am a stepmother of three orphans. I don’t have money, but this makes me feel good. My sister was six when she died, and I was 7 [at the time of earthquake]. I do it to make her happy.” (Code 6)

Some of the earthquake survivors who are capable of continuing their education attempt to help others by studying. Some even try to make their bereaved or dead parents happy.

“I tried to be a doctor. Any patient who is visited by me to me and doesn’t have money, I don’t charge him. I cooperate with the Red Cross voluntarily. If my family had gotten treatments in time, they would have been alive right now. I became a doctor to help my people if necessary.” (Code 7)

Religious Strategies

One of the strategies for dealing with the persistent crisis of an earthquake is resorting to religious beliefs. Strengthening religious beliefs by reading prayer books and such religious texts as the Quran, participation in religious ceremonies and saying prayers are some of the religious strategies reportedly used by those who survived the earthquake in order to cope with multiple physical, mental and social problems. On the other hand, fatalism and ‘submission to the will of God’ help these children deal with problems after the earthquake.

“As I grew up, I realised that God is the only refuge. Whenever I have problem I say prayers instead of crying and sadness. These beliefs help me out of all pains.” (Code 1)

Resilience

Resilience is one of the other strategies that children who survived the earthquake use in the process of rebuilding their lives. Resiliency is the result of a shift from being risk-oriented to coping with and modifying stress factors, which leads to the preservation and promotion of health in many aspects. Patience and perseverance, improving self-confidence, seeking familial and social support, and optional forgetfulness are some aspects of resiliency. These earthquake survivors often try to forget what happened in the past through emotional suppression.

“Whenever I give up, I go to my friends and family. My mother understands me very well. She knows how much I was hurt then because I was a kid. I unburden myself [in] this way, and I have withstood many times [through] the help of her.” (Code 8)

Internal Evolution

Internal evolution refers to self-monitoring and positive psychological changes related to the earthquake. Self-monitoring and knowing oneself, others and God are some of the reported positive consequences of the earthquake. These respondents believe that knowing themselves and God gives them the power to deal with the chaos and emotional gaps caused by the earthquake.

“The earthquake was a very bitter memory. But it built me. It made me resistant. It made me appreciate people. It made me more patient. It made me experience things which were productive. When I wonder, I think that it taught me that such moments won’t happen again. I knew my abilities and myself. These made me successful.” (Code 7)

Discussion

According to the findings of this study, the first step in the lives of children who have survived the Manjil earthquake involves the unexpected encounter with the disaster. King (2006) believed immediately after the incident, the children experienced different reactions of shock and horror. These emotional reactions include a range of physiological, psychological, social and behavioural reactions13. More than other age groups, children are more prone to distress when faced with an earthquake disaster14. The results this study showed that in the early ravages caused by the earthquake, the loss of parents and shelter may have put the children at risk of harm and mistreatment. Therefore proper planning in crisis management, paying attention to the characteristics and needs of vulnerable groups including children, and comprehensive support can reduce the risk of mistreatment15. Based on the results of this study, there is a need for plans to provide long-term services.

It is important to note that threatening factors are persistent due to the long-term and sometimes permanent effects of earthquake disasters, and children are in great need of care at all stages of their lives. Unfortunately, rehabilitation and long-term services are marginal in disaster management planning16. Under these circumstances, there is a significant increase in mortality and a notable decrease in the physical, psychological and social function of these children17. Even if these services exist in society, they do not cover all survivors due to their unavailability and young age. Therefore, providing and sustaining long-term rehabilitation services must be considered as priorities when it comes to children survivors of natural disasters18.

The results this study also indicated that temporary social support and the subsided emotions of people and charities over time cause survivors to be deprived of support services, especially long-term emotional support. According to this group of survivors, after almost 24 years, the disaster has been forgotten and has disappeared from people’s minds. Bolton et al ( 2000) believed this is associated with the lack of understanding by people, especially non-peers19. Concealing the feelings of others and social isolation are some of the strategies that this group of survivors may use to face such reactions20.

Further, this study’s results showed that children whose other relatives are given custody and children who are adopted have the most problems. Since relatives are given priority in adopting a child, in most cases the economic status, emotional situation and social health of these families are not considered before the adoption. The new family members cannot provide a safe haven for these children because they are in crisis and are suffering from many financial, physical and mental problems. These children may experience violence, misbehaviour and secondary displacement in new families21. In such circumstances, these children feel that they are a burden, and experience a lack of opportunity in education, marriage, or suitable occupations22.

Regarding the fact that many of the participants of the present study have lost one or both of their parents in the earthquake, and given that some live with family members in an environment which is not physically, mentally and emotionally stable, most of these survivors face severe emotional issues as their future relationships are threatened. The results of McDermott’s (2005) study showed that distrust of friendly and effective communication with others on one hand and emotional gaps on the other can all cause behavioural and emotional conflicts, and can bring about short-term emotional and social communication issues23.

Failures in communication and constructive attachments cause these child survivors to experience failure in marriage and family life24. Therefore, comprehensive services such as counselling, health care and welfare services are necessary25. This study’s findings also showed that sometimes, parents do not succeed in their parental roles in supporting their children due to the distress they experience as a result of the earthquake. In such cases, these parents in turn can pose a risk to their own children. The results of Gertrud’s (2004) study showed that parents who were themselves severely impacted by disaster reported a reduced ability to assess their children’s reactions, and thereby were unable to provide optimal care2. Interestingly, these parents’ support strategies mirrored the early intervention recommendations put forward in the psychological first-aid guidelines which is a well-accepted and promising practice for helping children after disasters2. In the present study, mental nostalgia is one of the internal factors affecting the lives of those who survived the earthquake as children. These people retrieve memories when they face scenes that they consider as similar to events at the time of the earthquake. Hafstad et al (2004) believed nostalgia of past memories threatens their mental and emotional health during different stages of their lives2.

Believing in bad luck is another internal factor affecting the lives of those who were children earthquake survivors. Similar studies have shown that these beliefs can suppress a person’s effort in coping with stressful atmospheres, and can keep individuals from trying to improve their family and social lives22. Believing in bad luck can also deter this group of people from pursuing their previous dreams and wishes, as well as from social communication26. As the data in this study showed, one of the factors causing threats to the health of these children survivors is non-specific care. It should be noted that ignoring the needs of these survivors, considering the services superficially and providing those services temporarily may threaten their health in various aspects27.

In order to prevent more permanent damages to child survivors, we have to train individuals, aid workers and volunteers to bring up people from under the rubble correctly, identify specific needs of children survivors, and further care provisions28. Participants in this study have tried to resort to strategies such as the development of social communication, spirituality, and psychological strengthening to maintain stability and balance in their individual, family and social lives. In fact, other studies have emphasised religious beliefs as a facilitator of these survivors’ life processes29. Developing social relationships and friendships help improve the quality of survivors’ lives30.

Conclusion

According to the results of the present study, providing non-specific and temporary services is one of the factors affecting the life processes of children who have survived the Manjil earthquake. Training aid workers to consider the specific needs of children at the time of rescue operations could contribute to improving the health of this group in different aspects. Considering effective and comprehensive rehabilitation programs in Disaster Management policymaking can prevent persistent complications caused by earthquakes and other natural disasters. The results of this study also showed that some of the factors threatening the health of children earthquake survivors include homelessness, living in care centres, and living with risky parents. Planning and taking action to identify misbehaviour in this group of children, as well as raising public awareness (particularly for parents) on how to manage a disaster, are public health priorities. Providing public counselling services to children survivors as well as their parents will help to solve the potential psychological problems that threaten the well-being of children survivors.

Further, this study showed that children have tried to use different strategies in the process of their lives to maintain and promote their personal and social life. Strengthening religious beliefs and encouraging children survivors to participate in social groups (especially peer groups) will help them to feel understood, safe and alleviated of many negative feelings resulting from their experience of a natural disaster.

Appendix A: Interview Guide Questions

1- Can you tell me about your experiences after the earthquake?

2- What happened to you at the moment the earthquake happened?

3- Please talk about the harms happened to you.

4- How do you describe the life after the earthquake?

5- What has helped you to deal with the earthquake?

6- What does earthquake mean to you?

7- How was your life?

8- Would you please review a day of your life?

9- Which factors have helped you at the moment of the earthquake or after that?

Limitation

Among the limitations of this study, restrictions in generalization of the results can be mentioned. As interview method was used for data collection, the veracity of the interviewees might have affected the results. Therefore, conducting more studies focusing on triangulation methods is suggested.

Corresponding Author

Dr Fatemeh Ghaffari. Email: [email protected]

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

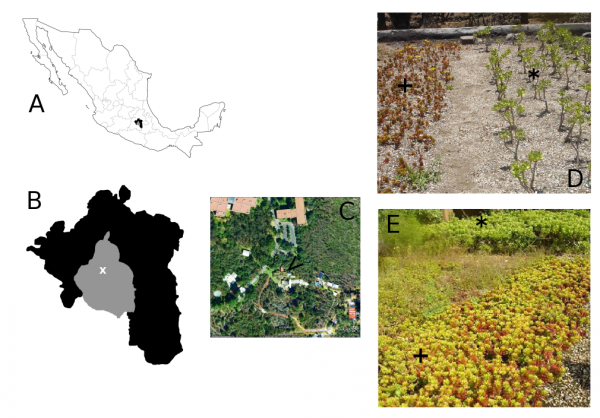

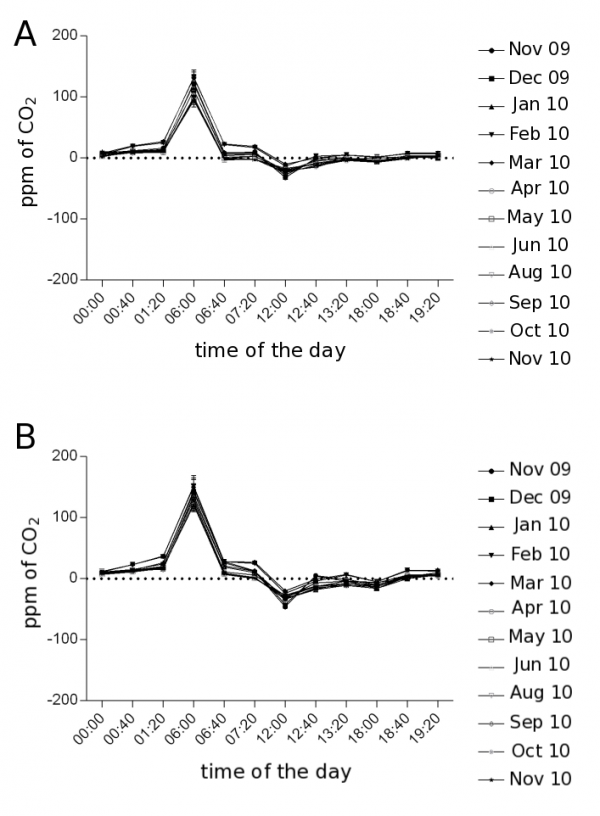

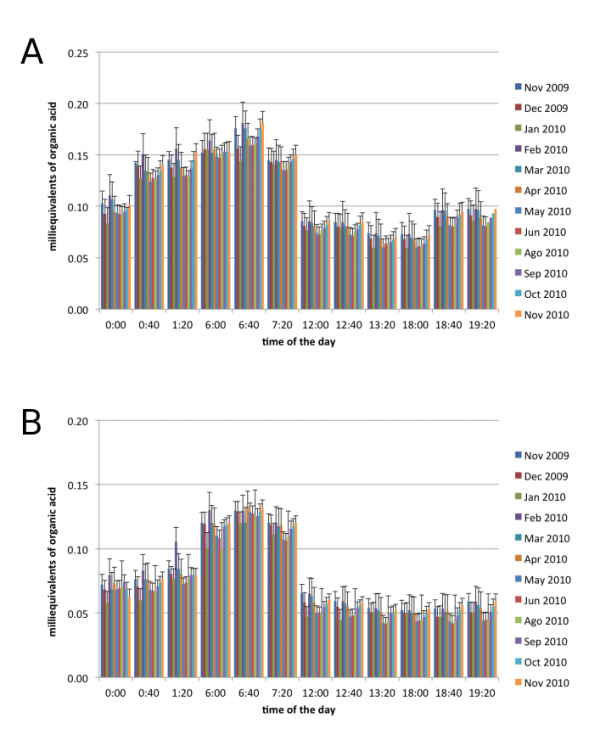

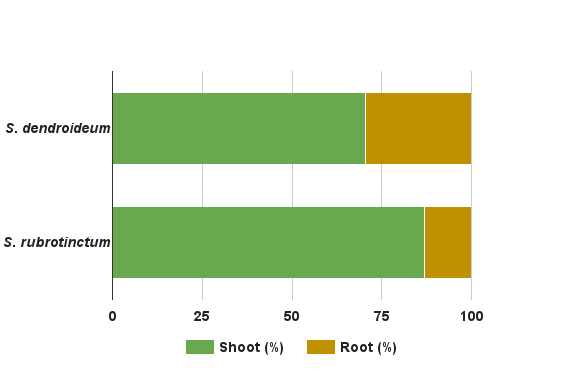

METHODS: Here, we quantified the carbon sequestration capabilities of two ornamental succulent plant species, Sedum dendroideum and Sedum rubrotinctum, which require low maintenance, and little or no irrigation. To obtain a detailed picture of these plants’ carbon sequestration capabilities, we measured carbon uptake on the Sedum plants by quantifying carbon dioxide exchange and fixation as organic acids, during the day and across the year, on a green roof located in Southern Mexico City.

RESULTS: The species displayed their typical CAM photosynthetic metabolism. Moreover, our quantification allowed us to conservatively estimate that a newly planted green roof of Sedum sequesters approximately 180,000,000 ppm of carbon dioxide per year in a green roof of 100 square meters in the short term.

DISCUSSION: The patterns of CAM and carbon dioxide sequestration were highly robust to the fluctuations of temperature and precipitation between seasons, and therefore we speculate that carbon sequestration would be comparable in any given year of a newly planted green roof. Older green roof would require regular trimming to mantain their carbon sink properties, but their carbon sequestration capabilities remain to be quantified. Nevertheless, we propose that Sedum green roofs can be part of the long-term solutions to mitigate the air pollution crisis in the Mexico City Metropolitan area, and other “megacities” with marked seasonal drought.

]]>Resumen

INTRODUCCIÓN: En los primeros meses del 2016, la Ciudad de México y su zona metropolitana conurbada ha experimentado una de las peores crisis de contaminación del aire de la última década, urgiendo a las autoridades a tomar medidas drásticas a corto plazo. A fin de proporcionar elementos para investigaciones de sostenibilidad a largo plazo quisimos dar a conocer nuestros resultados de monitoreo de captura de carbono por plantas de azoteas verdes. Estas azoteas son una forma de naturación a gran escala, que constituyen una alternativa para mitigar parcialmente el incremento de dióxido de carbono en las áreas urbanas.

MÉTODOS: Nosotros cuantificamos la capacidad de captura de carbono por dos especies de suculentas ornamentales, Sedum dendroideum y Sedum rubrotinctum, que requieren bajo mantenimiento y nula o poca irrigación. Para tener una idea detallada de la capacidad de captura, medimos el carbono tomado por las plantas durante el día por un año en plantas de Sedum localizadas en una azotea verde en el sur de la Ciudad de México.

RESULTADOS: Estas especies presentan el metabolismo fotosintético CAM. La cuantificación obtenida nos permite estimar que una azotea verde de Sedum de 100 m2 captura aproximadamente 1.8 x 108 ppm de CO2 por año.

DISCUSIÓN: Los patrones de CAM y de captura de CO2 fueron bastante robustos a las fluctuaciones de temperature y precipitación estacionales, por lo cual especulamos que la captura de carbono sería similar en cualquier otro año de una azotea verde de reciente plantación. Azoteas de mayor edad requerirían podas regulares para mantener sus propiedades de captura de carbono, sin embargo, no se sabe qué capacidad pueden tener para capturar carbono. No obstante, proponemos que las azoteas verdes plantadas con Sedum son una parte de la solución a largo plazo para mitigar las crisis de contaminación del aire en la zona metropolitana de la Ciudad de México, y de las megaurbes con una marcada estación de sequía.

Author Contributions

MCO & JRS designed the project; MCO performed experiments; MCO and UR analyzed results; MCO & JRS provided materials and reagents to perform experiments; MCO & UR wrote the manuscript. MCO: orcid.org/0000-0001-6618-4920; UR: orcid.org/0000-0001-5088-2679

Corresponding Authors

MCO ([email protected]) and UR ([email protected])

Keywords

Plant physiology, Crassulacean Acid Metabolism, urban biology, megapolis, environmental crisis, plant urban physiology, Sedum dendroideum, Sedum rubrotinctum, air pollution, bioremediation

Competing Interests statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Data Availability statement

Raw data available on doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.3395887

Introduction

Deforestation, urbanization and the intensive use of fossil fuels are some of the main causes of the increase of carbon dioxide (CO2) since the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, contributing to the current changes in climate 1. These CO2 levels have gone from 280 ppm to 380 ppm, and it is estimated that levels could reach 770 ppm by the end of the twenty-first century 2. This dramatic increase in CO2 levels, particularly in urban regions, has caused a change in the global carbon cycles 2,3. Thus, vegetation plays a crucial role in urban ecosystems, by sequestering carbon excess, storing carbon as biomass, and releasing oxygen and water vapor through evapotranspiration. In recent decades urban ecosystems have drastically expanded and increased in complexity due to mass changes in economic activities, the migration of people from rural environments to cities 4, and widespread use of motorized vehicles. Unplanned growth of urban areas sometimes produces “megacities” where space becomes a luxury, and vegetation is often sacrificed to give way to urban infrastructure.

This is the case of Mexico City and its Metropolitan Area, otherwise known as Zona Metropolitana del Valle de México (ZMVM). This is the fourth most populated metropolis of the world and the largest in Latin America 5,6, with more than 20 million inhabitants according to a 2010 census (INEGI, https://www.inegi.org.mx). According to the Mexican Fifth National Communication to the United Nations on Climate Change, CO2 emissions increased 23.6 % from 1990 to 2010, coming mainly from fossil fuels, land use changes, and lack of silviculture. In the first third of 2016, the ZMVM is experiencing the worst environmental crisis of air quality of the last decade, demonstrating that short-term solutions implemented since the 1980s when the air quality became extremely critical, have been insufficient. In 2009, the Dirección de Reforestación Urbana, Parques y Ciclovías de la Secretaría de Medio Ambiente del Distrito Federal (today Mexico City), pointed out that poor metropolitan growth planning, deficient management of green areas, lack of legislation on urban vegetation, and poor conservation efforts, have all contributed to the deterioration of the green urban landscape, and their associated environmental and social benefits. In addition to better management of public green spaces, it is necessary to urgently reassess the strategies towards sequestering carbon and other air pollutants. To archive this, the mega-polis inhabitants must play an active role in tackling the challenge.

Besides reducing gas emissions from fossil-fuel combustion, in other cities the promotion of urban vegetation has been adopted as a method to eliminate pollutants and purify the air 7,8. Because of the scarcity of space in large cities, a strategy to increase the vegetation cover is through the implementation of what are known as green roofs, eco-roofs, living roofs, or roof gardens . Green roofs are defined as any rooftop covered by layers of roof coating, plant substrate, and vegetation 9. Green roofs have been associated with multiple environmental, ecological, health, and aesthetic benefits 3,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Despite the relevance of green roofs as a potential solution to improve air quality in “megacities,” there is scarce experimental data in planta on the capabilities of green roofs to uptake CO2. Therefore, quantifying the green roofs’ capacity to sequester and retain CO2, pollutants, and other greenhouse gases is imperative under the current environmental crisis scenario, particularly in the ZMVM.

Currently there is robust evidence supporting the use of plants to capture air pollutants. However, we still need in planta qualifications on the role of green roofs to capture pollutants 16. NOx, SO2, PM10 and O3 are among the pollutants that have been quantified as sequestered by green roof vegetation 7,17,18,19. Experimentally, CO2 green roof-uptake quantification seems to be rather challenging, and mostly estimated using proxies, such as biomass accumulation 13,20, models of carbon-oxygen balance 21,22, macro-estimations of vegetation cover in large cities 7,13,23 or methods more appropriate for urban forests, rather than herbaceous plants 17.

In their studies measuring carbon uptake on green roofs, Li et al (2010) measured the CO2 uptake in a green roof, placing the IRGA within grass-shrubs and comparing it to a location outside the shrub, obtaining an average of 12.9 mg C m-3 per day 8. Ondoño et al (2016) estimated carbon and nitrogen uptake by quantifying the element composition on a green roof of weedy and grassy plants, obtaining 36.52 g C m-2 at the end of 9 months 24. Regarding Sedum green roofs, Getter et al (2009) quantified carbon storage in green roofs of several Sedum species, by measuring accumulated dry matter in the shoot, root, and soil, obtaining 160 g C m-2 during a two year period 13. More recently, Whittinghill et al (2014) measured carbon content and dry weight, and found that Sedum green roofs captured 1940 g C m-2 in a 14-month period and 3910 g C m-2 in a 12-month period 20. Overall, previous studies support the use of green roofs, and particularly, of highly resilient Sedum species to improve air quality conditions, in particular in overcrowded urban areas. However, we still lack data on the carbon uptake by Sedum plants, measuring CO2 exchange.