Methods: The full systematic review applied standard systematic review methodology that was described in detail, peer-reviewed, and published before the research was conducted.

Results: While the science of humanitarian practice is still developing, a systematic review of targeting vulnerable populations in urban humanitarian crises shed some light on the evidence base to guide policy and practice. This systematic review, referenced and available online, led to further findings that did not meet the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria for evidence set out in the full review but that the authors, in their expert opinion, believe provide valuable insight nonetheless given their recurrence.

Discussion: These additional findings that did not meet criteria for evidence and formal inclusion in the full manuscript, but deemed valuable by the subject expert authors, are discussed in this commentary

]]>Introduction

This discussion compliments a full systematic review by the authors published by Oxfam on targeting in urban humanitarian crises: What practices are used to identify and prioritize vulnerable populations affected by urban humanitarian emergencies? A systematic review. Oxford: Oxfam GB.1 Given the rapid growth of cities that outpace public services and extreme poverty marks some, sometimes large, portions of these cities. Even before a crisis, many urban dwellers may live below the Sphere minimum standards and needs can often outstrip the resources that humanitarian aid can bring to bear for disaster affected and non-affected persons in these cities. Identifying the most in need to prioritize for aid can be difficult. The goal of the systematic review was to evaluate the evidence base on targeting vulnerable populations in urban humanitarian crises. Urban vulnerability translates into multiple specific needs and a wide range of need assessment tools and methodologies were reviewed as long as they had been used in an urban humanitarian emergency and its performance had been evaluated. The evidence base was thin but some concrete findings could be drawn to guide practice.

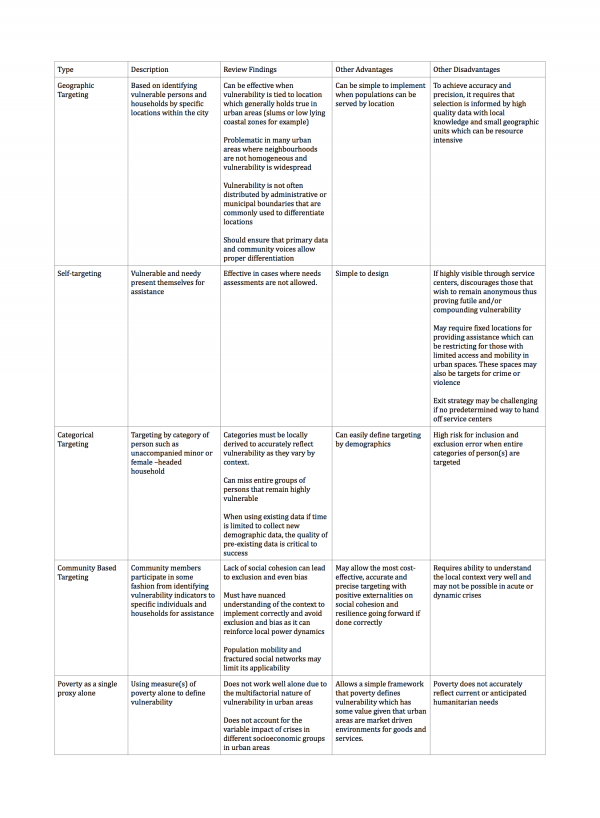

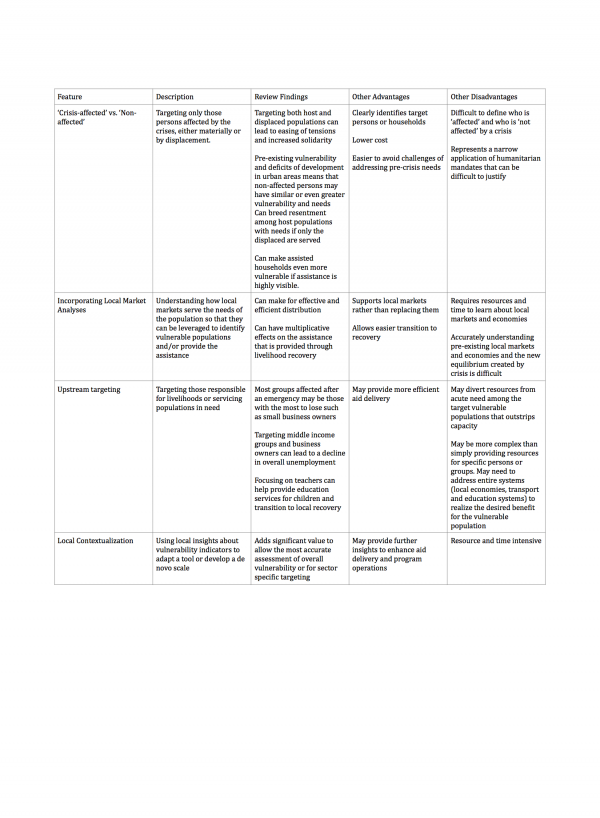

In addition to the studies and findings reported in the full review, we identified 16 reports that were relevant to the topic of the review by meeting criteria for initial screening, but fell short of meeting the criteria for inclusion in the formal evidence-based synthesis. The predefined inclusion criteria for inclusion in the systematic review required that reports a) described a targeting practice had been employed in an urban humanitarian crisis and; b) that the practice was evaluated in some form or another. Standard systematic review methodology was used and a protocol for the systematic review was reviewed and published prior to the research. For the detailed methodology used in the systematic review including key terms of reference please refer to the original publication. As expert authors, we believe repeated lessons within these 16 reports provide valuable insights, reinforce the full systematic review findings or represent promising areas of research for further study despite their lack of supporting evidence as defined by the full systematic review methodology. This editorial commentary on targeting was focused around these recurrent lessons identified through the same thematic analysis used in the full systematic review. These summary commentary lessons from the full systematic review and these additional 16 reports about targeting approaches and other features of targeting are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. These tables aim to provide a full accounting of our expert recommendations in an easily digestible format and represent a current ‘state of the art’ reflection of the our guidance on targeting practices for vulnerable populations in urban crises.

Given the overall lack of study, we argue that the absence of evidence does not necessarily make these lessons untrue. In fact, their repeated nature would actually qualify them as valid findings according to other criteria and they may eventually be supported by evidence. We included examples from the 16 reports within the commentary to provide a clearer depiction of the content discussed, not as anecdotal evidence.

Commentary from Recurrent Lessons

Targeting ‘Affected’ vs. ‘Non-Affected’ populations does not work well

In addition to targeting by displacement status, as highlighted in the full systematic review, targeting only persons affected by a crisis, those experiencing some loss as a result of the crisis, does not generally work well in the urban space even when resources are limited. Targeting only persons directly affected by the crisis such as those that suffer material or bodily harm directly by the crisis does not identify all or even the most vulnerable in urban humanitarian emergencies.2 To begin with, delineating who is ‘affected’ is difficult. Urban areas are complex systems in which a humanitarian emergency can have many indirect impacts on the ability to keep safe and obtain necessary goods and services making it difficult to truly define ‘affected or ‘non-affected.’ A flood may cause food prices to spike or foment violence that impacts households not directly damaged by floods themselves. Defining ‘affected’ is a critical challenge in this strategy. Additionally, chronically high levels of vulnerability within urban environments, sometimes themselves classified as (or otherwise meeting the criteria of) humanitarian crises, result in increased levels of baseline vulnerability among host or pre-crisis populations.3 Even after a crisis strikes, these poor but ‘non-affected’ populations (however defined), may be as or more vulnerable than persons that are directly or indirectly affected. The needs and vulnerability of ‘unaffected’ urban populations, especially the urban poor, may fall well within humanitarian imperatives and the goals of the targeting program. Targeting by ‘disaster affected persons does not work well in urban areas to accurately identify all or the most persons in need of a specific humanitarian aid interventions services.

Targeting upstream individuals and groups can enable recovery for the most vulnerable

Focusing on employers or individuals who are responsible for the livelihoods of others can be a means of returning beneficiaries to baseline livelihoods more quickly.4 In their review of cash transfer programming across a variety of settings, IIED highlighted the importance of keeping in mind that the most-affected populations, and those vital to post-crisis recovery, may actually be the relatively better off, such as small business owners who employ lower income individuals.5

After the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti, targeting in one program focused on small business owners in an effort to help businesses remain in operation. Targeting focused on both the low-income as well as the middle-income groups “for two reasons: first, the middle groups were also badly affected by the earthquake and secondly, the services and activities carried out by the middle groups play a vital role in the recovery [of] the economy.”6 Focus groups in Haiti identified many vulnerable groups who were in need but who had not been targeted to receive services, including teachers. These focus groups identified the key link teachers provided in maintaining the human resources necessary for the education system and concluded that teachers should be prioritized as beneficiaries.7Incorporating this form of upstream targeting can facilitate smooth exit strategies and shifts the focus of targeting to engaging local actors.

Poverty is a useful but imperfect proxy for vulnerability when used alone

Targeting vulnerability more generally based on poverty alone as a proxy may be appropriate in urban settings but requires detailed understanding to target correctly. A snapshot of income or assets alone does not account for an accurate understanding of vulnerability. As identified by MacAuslan and Farhat, poverty measures alone do not account for current or anticipated needs or the impact of a crisis on various socio-economic groups.8 Socio-economic variables including an assessment of coping strategies needs to be incorporated into targeting processes for more accurate targeting. Someone with less poverty may in fact be more vulnerable because they have more to lose or their means of living in the urban area are dependent on certain urban functions that can be impacted by a crisis or they may lack sufficient coping mechanisms. Urban areas constitute an economic environment with goods and services driven by markets and thus poverty is key but does not wholly reflect vulnerability, which is multidimensional.

Protection concern may drive vulnerability more than other measures in some situations

Despite having low vulnerability according to various indicators such as income or displacement status, concerns about safety may actually drive vulnerability in some cases. These protection concerns may override many other indicators of vulnerability.9 Protection concerns, however, may be linked to one of these specific indicators such as status as a refugee, residence within a conflict zone or engagement in child labour. For example, although a household may enjoy a higher socioeconomic status, female heads of household or specific ethnic groups may actually have limited access to basic goods and services due to constrained mobility from insecurity and fear of violence in the urban space. Targeting approaches should add a protection lens to vulnerability analyses keeping in mind that safety and security can be paramount to wellbeing.10

Geographical targeting requires more detailed analysis given the density and heterogeneity of cities

Geographic selection of urban areas to identify vulnerable populations by specific location, such as slums or low-lying coastal zones, can be a very effective process for targeting.8,11 However, because many urban areas are not homogenous, care should be taken to identify geographic units that are smaller and not restricted to typical municipal or administrative boundaries.5,9,12 Vulnerability is heterogeneous and ignorant of such boundaries in urban areas.

Community participation and community based targeting are key to effective response but must be used with caution

Many of the reports point toward the importance of community perspectives to help ensure that vulnerable areas and populations are not overlooked.5,8,9,13 Incorporating community perspectives can lead to locally derived measures of vulnerability as described in the full systematic review. Such locally derived measures, however, take time and resources to develop. They may often lose comparability between contexts depending on their design. Yet comparable tools can be developed. For example, a scale based on local coping strategies can allow comparison if variations of coping can be applied to the same quantitative scale. These trade-offs must factor into their selection.

Community based targeting (CBT) or participatory targeting whereby the community directly identifies vulnerable persons or households is a growing practice in humanitarian interventions and compliments trends toward locally driven processes that are inclusive and suited for area based programming. The data from these practices is thin and of low quality but common lessons are repeated. In general, incorporating community knowledge is clearly vital to good targeting, but participation can take many forms.

Lessons indicate the importance of having a nuanced understanding of the motivating factors driving individual participation in community-based targeting, as well as familiarity with local power dynamics and knowing whose voices are being heard.4,14 As such, defining the community is critical and must be done carefully. Reports suggest that, in many ways, the community-based targeting practices relied upon in rural areas may not be relevant in urban contexts. Two reports highlighted the greater risk of using CBT in urban areas because close geographic proximity in urban environments may not necessarily indicate familiarity within communities as much as it may in rural areas, due to population mobility and fractured social networks.5,15 As a result, CBT that relies too heavily on community leaders or a small subset of people to identify beneficiaries can lead to biases and systematic exclusion of vulnerable groups or individuals more than in rural areas.5,15 Maintaining accuracy with community-based targeting requires triangulation and verification of information, as the most vulnerable neighbors may be unknown to or marginalized by community leaders.16Community engagement that unwittingly reinforces any pre-existing marginalization will do more harm than good.

Measuring food security an take many diverse forms but requires detailed analysis

Papers on targeting for food insecurity were more numerous than other forms of sector-specific targeting, with 10 of the 21 evidence-based articles in the full systematic review dealing specifically with food security. Indeed, many of the evidence-based lessons and recurrent lessons above came from food security reports yet applied more generally as well. There was a lack of evidence directly comparing measures but a few insights are found in the various reports.

Targeting for food aid can measure a variety of characteristics such as consumption, purchasing power, access, nutritional status or coping strategies. These measures take multiple forms from a universal composite index to a locally derived context specific scale. All of these approaches come with their own advantages and disadvantages.17 Measuring nutritional intake or status provides only a snapshot of current or past consumption patterns. It does not accurately reflect food security, which is a latent property representing the ability to secure adequate food. Several other methods such as the Household Food Insecurity Assessment Scale attempt to do just that.18 By identifying a few key indicators, assessments may rapidly and efficiently identify vulnerable households and optimize targeting without extensive data. Although food prices play a large role in food consumption in urban areas, poverty alone is not always the best correlate for food insecurity. To identify food insecure populations, understanding intra-household consumption patterns, capturing out of home consumption and the local coping strategies employed in additon to standard tools is key.

Involving local markets is important to targeting in urban areas while enhancing overall recovery

Markets are important to addressing vulnerability in urban areas. Multiple reports point toward the importance of market analysis as urban food security is closely linked to commodity prices, income opportunities and wage rates.19 One key insight from Oxfam programming after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti was that “a better understanding of crucial market chains can help lead to a more effective distribution of humanitarian resources, faster economic recovery and less risk of long term dependency on external assistance.” The program in Haiti relied upon an inter-agency Emergency Market Mapping Analysis (EMMA) as well as a 2009 baseline assessment of income groups within Port Au Prince to create wealth group profiles for households affected by the earthquake and to inform targeting.6

Programming aimed at improving market recovery post-crisis can also achieve the dual purpose of improving livelihoods as well as nutrition. The review uncovered several studies that provide specific examples of how effective targeting involving local markets improved livelihoods. In Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, a program aimed at improving the nutritional status of vulnerable households successfully used local millers to produce, and existing retailers to sell, a low-cost maize alternative—sorghum.20 Oxfam used cash transfers in Nairobi to help households meet food needs through local markets and found that, along with other services to support entrepreneurship, the program enabled 50 per cent of beneficiary households to initiate, strengthen or restart a small business, creating more vibrant local markets.21 Additionally, an evaluation of the canteen program in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake found that 87% of beneficiaries who received small business grants were able to restart an economic activity and 64% of the women participants were able to restart their business because of the canteen program.6

Vulnerability can be invisible

It is important to acknowledge that the most vulnerable persons may be those who try to stay invisible to authorities and even their neighbors, and therefore may be missed by the targeting methods discussed in this review.4 This need for anonymity makes them particularly vulnerable. Also, a lack of representative leadership structures among refugee communities may result in individuals being overlooked or invisible to members of their own community.22 One proposed solution is to provide discreet community drop-in centres open to all that allow invisible persons to self-target for protection or service provision.22 Another proposed solution to connect with beneficiaries is to publicize hotlines where beneficiaries can call and receive information about services.23 All of the proposed solutions for this population require focused study.

Table 1: Targeting strategies, review findings and other notable advantages and disadvantages to guide selection.

Table 2: Other features of targeting, review findings and notable advantages and disadvantages to guide selection.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The current evidence and recurrent lessons above do not point to one single best approach for targeting vulnerable populations in urban crises. As humanitarian programs have a wide variety of goals and urban contexts and crises vary, the complex nature of vulnerability makes it impossible to have one best approach for each situation. Any approach will have strengths and limitations and none will be perfect as needs may often exceed available resources. In addition to these technical limitations, the security situation and political context can also impact the selection of a targeting approach. While evidence to guide humanitarian practice accumulates further debates on the humanitarian system and financing will have to progress in ways that incentivize evidence based practice. Selection of targeting vulnerable populations in urban crises will have to weight the costs, benefits and feasibility of each approach and funding tied to evidence on how these three variables are assessed will be the best path moving forward.

Vulnerability in urban areas is complex and interconnected such that assessing sector-specific vulnerability seems inappropriate or at least less useful. A person’s health and nutrition for instance is related to their shelter, access to sanitation, livelihood and surrounding security. We believe the most vulnerable in urban humanitarian crises are best targeted using a collection of socioeconomic indicators along with in depth contextual understanding.

Given that local actors, including government, will play a larger role in humanitarian response and the knowledge that municipal authorities and pre-existing organizations have, leveraging pre-existing data will be valuable. Often these may be incomplete, outdated or biased but improving these sources of information beforehand could be prove useful and efficient. As development and humanitarian practice come closer together within a resilience framework, reducing urban vulnerability as part of development efforts could help inform targeting in the event of a humanitarian crisis. Practices for targeting vulnerable populations in urban crises should leverage urban development practice and tools in rapidly growing cities that aim to alleviate poverty and build resilience.

Additionally, as the local expertise of already established actors and the affected community itself can prove invaluable, community based targeting (CBT) should be developed and tested further. The success of such an approach will depend on local capacity and technical expertise. Entrenched biases and power-dynamics may also bend a very well-intentioned approach into exacerbating vulnerability and a nuanced understanding of this context is required. The recent focus on area-based programming leans toward using a CBT approach as a key component. Targeting approaches should exploit local knowledge and community based approaches with a nuanced understanding of these communities and power relations.

Finally, the most promising approach may in fact be targeting based on methods that can be locally contextualized and rapidly so given the important of balancing accuracy with speedily delivering aid. As spaces within cities can be micro-environments that differ from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, locally contextualized tools should be further developed and expanded. Research and practice should focus on developing and testing rapidly tools that can be quickly contextualized to the local situation.

Overall, the full systematic review and this commentary from recurrent lessons lay bare the general lack of evidence guiding practice in targeting the most vulnerable in urban crises. Focused research and funding for it, as discussed in the full systematic review, must be prioritized to ensure humanitarian practice is grounded in rigorous evidence.

Corresponding Author

Ronak B. Patel, [email protected]

Data Availability

All relevant data are included within the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare the following interest: DS serves on the Editorial Board for PLOS Currents: Disasters. He has not influenced or played any role in the peer-review, editorial decision making or publication of the manuscript.

Article

In 2004 I was honored to be interviewed for the Lancet medical journal’s Lifeline Series.1 I had just come away from a disastrous short tenure as the Interim Minister of Health in Iraq following the 2003 war. I had support from former Secretary of State Colin Powell to rapidly mitigate and recover the war related destruction of essential public health infrastructure and protections required as Occupiers under Articles 55 and 56 of the Geneva Convention (GC) that follow every war. Predictably, the loss of essential public health protections in food, water, sanitation, shelter, health, and energy leads to excess and preventable mortality and morbidity, numbers that exceed those from war weaponry by 50-70% or more.2 This plan was immediately squelched by an unprecedented decision within the Bush Administration that moved these post-hostilities humanitarian responsibilities from the State Department to the Department of Defense under Donald Rumsfeld. This decision claimed that US forces were not ‘occupiers’ but ‘liberators’, promptly reversing any previously planned public health recovery and rehabilitation. The State Department’s coterie of seasoned nation-building experts, including myself, was summarily replaced. Before leaving Iraq I publicly declared Baghdad a public health emergency but this too fell on operational deaf ears.3 Many in Iraq see that decision as the most egregious of policies enacted after the invasion, in which the elderly, children, woman and disabled primarily suffered the most. While the ‘liberator’ claim was debunked and reversed 18 months later, it was too late. Without a reliable public health data and surveillance system, also thwarted in the war’s aftermath, the political powers remained protected from further scrutiny. Thirteen years later, Iraq remains a public health emergency.4

The Lifeline interview asked several questions: “What did I believe was the most exciting field of science?” My answer: “Public health. It has the most potential and the least support.” The interviewer, surprised, stated that to date no one had ever mentioned public health. When asked what I thought was the greatest political danger to the medical profession I answered: “Political interference in public health.”1

My answer today would be the same. We continue to see how the decades old international legal framework is easily overwhelmed by political inaction, interference and moreover, struggles for relevance given today’s modern challenges. The reasons for humanitarian crises and how the world must respond to them have dramatically changed every decade.5 The 1945 United Nations (UN) Charter, International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and the 1949 GC was designed to protect humanitarian aid in cross border wars. Unfortunately, while the language remains relevant and attempts have been made to adapt to modern day intrastate wars, too few warring factions and signatory governments either respect, or are unwilling, incapable, or selectively and blatantly ignore the protections we in the humanitarian community found sacred. No longer is their assurance for the continued safety of citizens, military casualties ’out of combat’, vital public health infrastructure and protections, and humanitarian personnel in intrastate unconventional armed conflicts. As political oppression and armed conflict erupts, essential public health infrastructure rapidly disappears and populations flee. If one accepts that disasters keep us honest by defining the public health and exposing its vulnerabilities, the global community must emphasize prevention and preparedness and re-legitimize it under international law to ensure protective strategies that intercede in fragile states before they deteriorate to the point of no return.

More than a decade after the Iraq war, a broader brand of global health engagement has emerged yet public health’s role within that rubric remains in limbo, is operationally ignored, or is ill defined. What sanctioned interventions exist ‘under international law’ to protect the public health before conditions deteriorate? None are clearly defined. Working from existing laws of war, the ICRC, influenced by the consequences of Iraq and now Syria, acknowledge the overwhelming and dramatic “cumulative impact that stems from the complexity of urban system” collapse and their mutual dependence on country-wide large-scale inter-connected infrastructure loss that the health systems are not able to keep up with.6 The numbers killed or injured are unprecedented. While today we painstakingly attempt to document the loss of health personnel in war, there is no equal documentation of essential public health recovery personnel, especially in water and sanitation.6 Despite the desperate call for a renewed emphasis on disaster risk reduction in 2015’s Hyogo Framework for Action, the fledgling global community is fixed on interventions that still favor response over preparedness and prevention for natural disasters. But what if the consequences of a natural disaster, including that of climate change, are inextricably leading to conflict or war?

Today’s domestic and regional crises are increasingly under the influence of widely integrated global changes and forces defined by climate change, biodiversity loss, emergencies of water, food and energy scarcity and rapid unsustainable urbanization. These crises, initially slow moving, are increasingly severe affecting massive populations across many borders. Drought, crop destruction, and famine coincide with loss of vital aquifers. Whatever limited and often primitive public health protections remain, they have proved ineffectual, dangerously managed and selectively denied to the most vulnerable by those in power who persistently ignore wide ranging mitigation advances offered by the scientific community.

New legal preventive protocols and epidemiologic surveillance approaches are needed to protect civilians. Protecting the public health must be viewed both as a strategic and security issue requiring close collaboration with humanitarian, and military logistical and security personnel. Any attempt to redefine public health as a security issue must be coupled with efforts to develop a more comprehensive accounting of the human cost of modern-day fragile and ungoverned territories—not just warfare.

A mandate for a universally accepted system of preventive monitoring of more precise methods and outcome indicators that measure the effectiveness and efficiency of national health and public health systems is undeniable. However, health alone cannot solve these global health problems. While some standard indicators are already available, the most sensitive are often multi-and trans-disciplinary. For example, rates of dengue fever, which escalate when trash collection is inadequate, are sensitive indicators for economists of both poor governance and urban decay.7 The humanitarian community is far from realizing this goal. For instance, we do not know how to operate effectively in unsustained dense rapidly urbanized settlements, a most likely site of future major conflicts. Unless measures are taken to develop ways to include indirect mortality and morbidity, calculating the human cost of public health decline will remain an inexact process of estimation by political scientists, humanitarians and military analysts. Capacity to access vital information of the location, function and extent of destroyed essential infrastructure is currently “not accessible.”8 The lives at risk and those lost will remain unseen, uncounted and unnoticed—and the lessons for effective prevention and protections unlearned.

Crises only gain international attention when they result in conflict. The Syrian conflict is a case in point. From 2011 to 2016, 60% of Syria’s agricultural northeast and south suffered its worst drought, water shortage and crop failure, compounded by failures in governance and management. Poverty accelerated the exodus of farmers, herders and rural families to cities in the west fomenting today’s major sectarian war. Multiple public health interventions were available and could have ceased or mitigated the decline and population exodus.9 Similar lost opportunities for preventive engagement occurred in the Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Indeed, if all the forcibly displaced persons would be placed in one state it would be the 21st largest populated country in the world.10 Populations escaping from public health collapse—as internally displaced or refugees—will exceed those from warfare alone, further adversely affecting the fragile public health protections in host countries such as Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Greece. The humanitarian community, strongly adhering to the global political commitment of ‘responsibility to protect’ endorsed by all member states of the UN must also recognize that migrants have an equal right to live and thrive in the country and culture in which they were raised.11 Not surprisingly, many migrants to the EU have openly declared their dream to return to their native country.

UN sanctioned revisions and rewrites of the IHL and the GC are crucial. The ICRC reports that there is “still room to strengthen and clarify the existing legal framework” to “adapt to new realities”; and, talks of supplemented GC Commentaries that “will give state and non-state actors an understanding of the law as it is widely interpreted today so that it is widely applied effectively in modern armed conflicts.”12

More than ever, we need strong international humanitarian laws and an effective accountability and recourse mandate for those who fail to respect the laws that are in place. Why wait for conflicts to occur when we have a clear evidence-based global mandate to mitigate the obvious public health consequences? With public health infrastructure and protections “absent, destroyed, overwhelmed, not recovered or maintained, or denied to populations” it has become a massive global health emergency.13

While we have had ‘laws of war’ for centuries, is it time, in an increasingly globalized world plagued by public health emergencies, for laws of prevention? Public health protections are a human right. What can one hopefully say to an emerging global society’s credibility that it has the tools to wage war but not to prevent them? The scientific expertise exists to be a force in preparedness and prevention; the political will and international law mandates must follow.

Competing Interests

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of their affiliated institutions.

Corresponding Author

Frederick M. Burkle, Jr.: [email protected]

Introduction

The 10th annual Philippine National Health Research System (PNHRS) Week Celebration, from the 8th to 12th August 2016 in Puerto Princesa, Palawan, Philippines, brought together health researchers, policy makers and practitioners from across the Philippines. The conference theme Research and Innovation for Health and the Environment aimed to facilitate smoother exchange of health-related research among key stakeholders via ten pre-conference events, seven parallel sessions, and two plenary sessions. This year’s conference saw an unprecedented focus on Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR). The purpose of this publication is to formally document and communicate the key messages that emerged from the conference.

The 10th PNHRS Week Celebration placed the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (Sendai Framework) at the front and centre of its agenda, highlighting the growing recognition among researchers and policy makers of the need to bolster research in this area within the Philippines. The key DRR-focused events included the Pre-forum workshop on Framework for Disaster Research in Health, the parallel session National Health Research Program on Disaster Risk Reduction and the plenary session on The Philippines as a Research Hub on Global Health Innovations to Deal with Climate Change and Natural Disasters. These events highlighted key strengths and challenges of DRR research in the Philippines within the broader context of positioning the Philippines as a global hub for research and innovation in DRR.

The year 2015 has been noted as a historic year in international policy, with the finalisation of three landmark United Nations agreements. These are:

Further to these agreements, the Sendai Framework was followed by the UNISDR Science and Technology Conference on the Implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 in January 2016 which included in its recommendations the ‘Need for formal ‘‘national DRR science-policy councils/platforms’’ or a form of national focal points for science to support disaster risk reduction and management plans identified’ 3. A second conference on the implementation of the health aspects of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-20305 in March 2016 lead to the Bangkok Principles which aim to strengthen health implementation of DRR5. Additionally, the landmark paper of the 2015 Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change, called for health to play a larger role in tackling climate change, viewing climate change as an opportunity and necessary area of strengthened action for the health sector in coming decades 6.

Background to the impact of disasters on the Philippines

Widely recognised as one of the most disaster-prone countries in the Asian Region, and the world 7, the Philippines was ranked second on the World Risk Index in 2014 in terms of exposure and risks to natural hazards 8. The Philippines was also the 5th most affected country by natural hazards from 1994 to 2013, and ranked as the most affected country in 2013 according to the 2015 Global Risk Index9. Between 1993 and 2012, the Philippines experienced 311 extreme weather events, the highest number globally, and falls within the top ten countries in the world most affected by extreme weather7. Most recently, the Philippines was found to have the highest expected annual mortality, affected population, and loss in GDP globally in relation to climatic hazards 10. This data is to the exclusion of impacts associated with non-climatic, biological or technological hazards.

The country is exposed to a variety of hazards across all categories – natural, biological, technological and social hazards such as mass gatherings11. Several geographic factors contribute to the high natural hazard exposure of the Philippines, including the country’s location in the ‘Pacific Ring of Fire’ at the junction of two large tectonic plates, the Philippine Sea Pacific Plates and the Eurasian Plate, facing the Pacific Ocean12 and one of the most active typhoon belts in the world 13.

In addition to these exposure factors, significant vulnerability as a result of inequity in access to healthcare and social protection mechanisms, as well as rapid unplanned urbanisation and development in economic hotspots, contribute greatly to the disaster risks faced by the population and economy of the Philippines 8,14.

DRR in the context of climate change has become a national priority with structures established to address these challenges. The national government has enacted the Climate Change Act of 2009 (RA 9729) and established the Climate Change Commission at the national level 15. The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010 (DRRM Act, RA. 10121) has also been enacted and corresponding structures established 16. These structures are known as the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), and are replicated at regional levels, known as Regional Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Councils (RDRRMC). National frameworks and plans in DRR and climate change have been developed and are in various stages of implementation 17 with the sunset review of the DRRM Act currently underway. Within the Department of Health (DOH), health emergency preparedness and response structures are institutionalised at the national level through the Health Emergency Management Bureau18.

The combination of these three factors, the risk profile, experiences and established structures in DRR, positions the Philippines to potentially become an international leader and global hub for DRR. However, several aspects need strengthening to support the development of the Philippines as an international hub for DRR. The key areas for strengthening identified through analysis of the content presented at the PNHRS Week Celebration include: integrated national hazard assessment, strengthened collaboration, and improved documentation.

Science and technology innovations in the Philippines and areas for further development

In addition to the institutional structures mentioned above, the Philippines has relevant scientific and technical structures to contribute to the understanding of hazards and risks, and development of scientific innovation in DRR. These are coordinated by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), and include, but are not limited to, the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) and the Philippine Atmospheric Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), to contribute to the understanding of hazards and risks, and development of scientific innovation in DRR.

Local governments are mandated to mainstream DRR and CCA in their local Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) and Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP). It is intended that these plans use vulnerability analysis and assessment within an integrated DRR and CCA framework 19,20,21. Further to this, Health Emergency Preparedness and Response and Recovery Plans at a regional and local government level contain natural hazard assessments for their corresponding areas 21. These hazard assessments provide potential sources for contributing to a detailed and integrated all-hazard assessment for the nation.

Examples of recent innovations in hazard mapping and assessment showcased during the PNHRS Week Celebration include the Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards, known as ‘Project NOAH’ and ‘FaultFinder’. Both of these web-based applications providing information on various hazards in the country, including meteorological and climatologically hazards, as well as major fault systems and earthquake risk mapping. Using a layered approach to mapping hazards, Project NOAH, allows users to select or search for a location and provides weather updates, data on rainfall and river inundation, as well as real time information on rain, weather and tides. The web-GIS tool provides hazard maps for floods, landslides and storm surge. It provides updates on flood reports, information on jurisdictions and critical infrastructure, as well as an impact assessment in the event of a hazard (available at: https://noah.dost.gov.ph/) 22. FaultFinder maps active fault systems, and allows users to search active fault systems of interest using GPS location on their mobile device, by name of location, and by browsing a detailed map view (available at: https://faultfinder.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/) 23. These projects aim to advance scientific research and risk communication.

A health-based technological innovation cited by the Department of Health at the PNHRS Week Celebration was ‘Surveillance in Post Extreme Emergencies and Disasters’ (SPEED). Developed through a collaboration between the Philippines Department of Health and the WHO Philippines, SPEED uses web-based software to assist in gathering data relating to communicable and non-communicable diseases and conditions in extreme emergencies and disasters 24. SPEED gathers syndromic information from health facilities such as Evacuation Centers and Barangay Health Stations or Rural Health Units, and initial diagnoses from hospitals and private clinics 24. Data can be entered via manual encoding, SMS, or online. SPEED enables the monitoring of trends and early detection of disease outbreaks with the aim of providing timely and appropriate health response to minimise morbidity and mortality in an emergency or disaster 24.

Challenges in collaboration on DRR research in health was a key challenge noted by PNHRS conference participants. A key barrier to collaboration, which was noted by participants during the event, was the lack of awareness and documentation of DRR research and activities. Further to this, it was observed that there was limited representation of other government sectors, UN agencies, private sector and NGOs present at the event. Strengthened documentation of DRR activities, as well as involvement of these stakeholders in relevant future events will help to promote the establishment of the Philippines as a hub for DRR and build full cross-sectoral and cross-stakeholder engagement in the initiative.

Barriers to documentation of DRR research, policies and activities highlighted during the PNHRS Week Celebration include: lack of prioritisation of DRR research and documentation, as well as a lack of system and capacity for documentation. Prioritisation of DRR research is particularly absent in the context of health-related research, with the current National Unified Health Research Agenda for 2011 to 2016 making no direct mention of disaster-related research in health 25. While DRR research in health was acknowledged by panelists to be occurring, this research is happening on a limited scale, and is not included in existing national health research databases.

Two national registries for health–related research were promoted at the PNHRS Week Celebration, including the Health Research and Development Information Network (HERDIN) and the Philippine Health Research Registry. A recent search of these databases reveals limited documentation of DRR research in health and for those that were documented there was limited availability of related publications and outcome documents. At this point there exists no central system for documenting disaster-specific research. Key messages from the DRR sessions at the PNHRS Week Celebration included a need to prioritise and document DRR research if the country which could be developed as an output from possible global hub for DRR.

The conference participants considered that it would be beneficial to strengthen the documentation of DRR research and strategies to build the credibility and evidence base for the Philippines as an international exemplar for DRR and disaster risk management (DRM). To address the challenges in documentation, it would be helpful to consider the need for:

Proposal for the Philippines developing a Global Hub for DRR

Promotion of the Philippines as a global hub for DRR research and innovation to support the implementation of the Sendai Framework has the potential to strengthen DRR investment in the country. The establishment of relevant laws, structures, and technical capability demonstrates the importance of, and existing commitment to, DRR in the Philippines. These factors lend themselves well to this development of the Philippines as a global hub for DRR and DRM.

Experts and policy makers whom attended the PNHRS event frequently referred to the Philippines as a ‘laboratory’ of disasters in Asia. Panelists at the PNHRS identified the importance of climate change and the role of the health and the wider scientific community in developing the scientific and technological capacity of the Philippines in DRR. Within this context, panelists recognised not only the extensive risk profile of the country, but also the significant knowledge and experience developed in DRR and DRM through its established DRR structures.

The concept of developing a national focus in science and technology in the Philippines started more than two years ago as a key outcome of the partnership between the PCHRD and COHRED (the Council on Health Research for Development, accessible via this link: https://www.cohred.org/). Through this partnership the first Global Forum for Research and Innovation for Health in Manila in August 2015, “Forum 2015”, was hosted jointly by COHRED, PCHRD, DOH and DOST 26,27. The ‘hub’ concept intends to create a focus for national development, particularly through inter-departmental and inter-sectoral action, as well as international collaboration 28. Developing a ‘hub’ also aims to optimize the socio-economic impact of investments in science and technology.

Initial interest in the Philippines of becoming a leader in shaping the global research agenda in health and science more broadly was stated at Forum 2015. The event focused on how research and innovation can improve food security and nutrition, health in megacities and, most importantly, DRR. The DRR events that took place during Forum 2015, showcased examples in DRR from several nations, including the experience of the Philippines in strengthening and mobilizing local government units and communities for DRR 27. In the period following Forum 2015, COHRED and PCHRD outlined the field of concentration more sharply in a first concept paper prepared for DOST and DOH: the interface between science and innovation and the impact of disasters – or DRR – with health as a key outcome measure 28. This then became the basis for further internal and external consultations and for making this the focus of the 10th PNHRS Anniversary meeting in Palawan.

At the recent 10th Philippine National Health Research System (PNHRS) Week Celebration, the rationale for developing the Philippines as a hub for DRR was presented and well supported by the panelists from the PNHRS, the Department of Science and Technology, Department of Health and key national and international academic and private sector stakeholders present. During the plenary session, key stakeholders in DRR and health and the wider sciences and private sector demonstrated widespread support for the push to develop the Philippines as a global hub for innovations to deal with climate change and natural disasters, using an all hazard approach. Panelists in the plenary placed health as a central contributor to DRR, particularly recognizing that ‘zero casualty is not zero damage to health’ 29, and the need to reduce hazard exposure and vulnerability, as well as increase coping capacity within the context of health innovations for climate change and disasters 29. Panelists made note of the established structures and human resources that are already committed toward DRR in the Philippines, as well as the desire to share the experiences and expertise of the Philippines in addressing disaster risks 30. With the Sendai Framework providing a method to build research activities and outputs in order to enhance DRR capabilities, the Philippines could position itself as a global hub on DRR 31. However, there is a clear deficit in documentation and publication of these experiences and expertise, which needs to be addressed 32. Panelists also showcased the growing engagement of the private sector in strengthening DRR and clear support for developing the Philippines as a hub for DRR 33. Placing the Philippines at the centre of the converging points on health and the wider sciences addressing sustainable development, DRR and Climate Change Adaptation would be beneficial 34.

The positioning of the Philippines as a global hub could require significant financial investment, however, this has the potential to provide return on investment in DRR 35. An important reference was made to the triple dividend of DRR investment 36, where:

Overwhelming support by key political stakeholders was demonstrated for developing the Philippines into a global hub. This was echoed in the strong rationales presented by panelists in the DRR-related events, as well as by the attendees of the conference. The panelists of the DRR-related sessions clearly presented compelling reasons why the Philippines is well-positioned to become the global hub for DRR. These reasons include the disaster risk profile of the Philippines, experience in DRR and established structures necessary to support the initiative.

Conclusion

As a consequence of its disaster incidence, especially with regards to the frequency and intensity of climate-related extreme events, the Philippines is widely recognised as one of the most at-risk countries in the world, with a developed strength and experience in DRR. This conference demonstrated the emergence of commitment towards using these experiences to strengthen DRR at Barangay, local, regional and national levels. The equal commitment demonstrated towards sharing these outputs with other at-risk countries globally is the driving force behind developing a global hub in the Philippines. The event also highlighted health research as a pivotal area for development in strengthening DRR in the Philippines towards the development of a global hub.

The commitment to the hub was announced at the 10th Philippine National Health Research System Week Celebration. Continuing work to determine what this might mean and how this concept might develop, particularly in the context of science and technology for health in DRR, will be undertaken prior to the presentation at the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction to be held in May 2017 in Cancun, Mexico on 22-26 May. The Global Platform is the premiere international forum dedicated to the international DRR agenda and the 2017 Global Platform will be the first opportunity for initial assessments of the progress towards the Sendai Framework (The Global Platform website can be accessed via this link: https://www.unisdr.org/conferences/2017/globalplatform).

Competing Interests

The authors would like to make it known that Virginia Murray is an editor on the Review Board for PLOS Currents: Disasters.

Corresponding Author

Primary: Banwell, Nicola M.; Email: [email protected]

Secondary: Opeña, Merlita M.; Email: [email protected]

Introduction

Disasters regularly have devastating effects on populations worldwide 1,2. To assist affected countries an increasing number of international emergency medical teams has been deployed 3. Concerns regarding the standard of medical care provided and the lack of preparedness of the teams have been raised. Health practitioners have been observed to work outside their scope of practice and license 4,5, and teams have lacked the basic capacities and means to be fully self-sufficient 2,6. Additional concerns have been highlighted regarding the lack of cultural awareness and coordination with local authorities as well as international agencies 7,8,9. More recently, the response to the West African Ebola epidemic has shown critical gaps in the timeliness, coordination and effectiveness of international emergency medical teams responding to outbreaks 10.

The ‘Foreign Medical Teams’ (FMTs) initiative evolved in 2010 under the umbrella of the World Health Organisation (WHO), the Global Health Cluster and other actors, with the aim to improve the quality and accountability of international emergency medical teams responding to disasters. In 2013, the FMT Working Group published a first edition of the ‘Classification and minimum standards for Foreign Medical Teams in sudden onset disasters’, in which capacities, services and minimum deployment standards for FMTs were defined 11. A global list of quality assured and classified FMT organizations was launched in July 2015. A change of name from FMT to Emergency Medical Teams (EMT) with a pre-fix to differentiate International and National teams (I-EMT and N-EMT) was endorsed at the global meeting held in Panama in December 2015. This was in recognition of the importance of national and international teams working collaboratively to maximise the response to large scale health emergencies (Table 1).

Table 1. EMT and disaster related definitions

The World Health Assembly 2015 recognised the need for a global health surge capacity and the establishment of the Global Health Emergency Workforce (GHEW), of which the EMT initiative is a part. The GHEW aims to improve coordination, readiness and quality assurance in the deployment of EMTs and individual experts such as those deployed through the Global Outbreak Alert and response Network (GOARN) and other networks and partnerships 12.

To improve the quality and professionalism of deployed teams, a coherent approach to education and training has been identified as a key next step 8. A standardised learning framework is needed to assist EMTs to prepare for response and allow quality assurance mechanisms for the EMT initiative. Organisations wishing to be EMT classified will be required to reveal their training strategies.

Multiple organisations and universities have developed education and training programmes for disaster and emergency response; with a significant variation in scope, curriculum and quality 13,14,15,16. The lack of common standards to guide education and training design and provision have been highlighted 13,17,18. In addition, many of the proposed training models are focused on individuals, rather than multidisciplinary EMTs 19. The so called ‘competency-based models’ have been recommended as the basis for education and training in the disaster field by several authors 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Such models are promoted as a way to standardise the training of individuals and contribute to the professionalisation of the discipline, but reviews of available competency models have shown limitations in their practical application 18,29. Although some authors have suggested possible ways to facilitate their alignment to practice 30,31, no competency models have led to a systematic and operationally focused framework to guide EMT organisations through an agreed training pathway for their teams.

The aim of this study is to explore and reflect on current practices related to disaster education and training and suggest key components for an operational EMT learning framework. This targets primarily I- EMTs.

Methods

This work has evolved out of the EMT process in which the authors are involved at different levels. The authors hold extensive experience in both medical field work in disaster contexts and disaster training development and implementation. Based on this, a first group (NAC, AH, IN, JvS) was formed to develop an EMT operational training framework that would contribute to quality and accountability mechanisms within the EMT initiative. A literature review was done compiling available literature from trainings and educational frameworks within the field of disaster medicine. Published literature search was performed using PubMed, EMBASE and Google Scholar. Since a limited amount of references about operational training was found, a search for grey literature followed. That included information from internet sites and other information made available for the authors by EMT organizations. The results were categorized and discussed by NAC, AH, IN and JvS, and a first draft with training recommendations was presented to the expert panel consisting of the remaining authors. Following sets of 5 revisions a final Global Operational Learning Framework was defined. The results presented are based on the discussion process that lead up to the framework.

Results

Current education and training for disaster and emergency response

Mainly individual education and training options are available to help prepare professionals engaging in disaster response. Individuals can strengthen existing professional skills and develop technical and context specific capacities through Masters level studies or short courses delivered by universities, training agencies or EMT organisations themselves, many of those trainings being recently compiled by Jacquet et al. 13. Two papers also gather a comprehensive compilation of postgraduate education programmes related to disasters offered in North America and Europe 14,15. Delivered online or face-to face, the numerous available courses cover multiple subjects; as broad as Global Health or as specific as nutrition or logistics in low-resource settings. The previously mentioned competency based models, mostly compiled in two systematic reviews 18,29, aimed to guide standardized curriculum design but their application in practical courses have not yet been documented. Training modalities also vary, from theory-based lectures and discussions, to case-scenario exercises and simulations 14,15.

Although it is acknowledged that EMT deploying organizations provide team training little evidence of their practices is available. The training approach followed by strong and experienced EMTs and organisations involved in emergency response have hardly been studied, even if many lessons may be learnt from their experiences. These organizations comprise emergency teams from international organizations, governments or well-known NGOs, as well as police, Fire and Rescue, ambulance services or militaries. They often follow an operational approach to training, immersing their teams into contexts they will likely be exposed to once in the field. Simulations, teamwork, pre-deployment preparation and the inclusion of regional and national actors are key features of their training practices 32,33. Table 2 illustrates some examples of these practices, which should be especially considered when designing an operational approach to training for EMTs.

Table 2. Examples of emergency training by relevant EMTs and emergency organizations

Recommendations for a global operational learning framework for EMTs

After a critical analysis and discussion around EMT education and training current practice and needs a systematic approach linked to current WHO EMT standards is presented. It recognises both individual competencies and team dynamics within the procedures of a field deployable agency as being equally important factors for an effective response.

1. Three-step learning process

The three steps proposed below (Figure 1) are designed to:

Fig. 1: Three-step learning process for EMTs

With different formats and levels of complexity, several authors have already mentioned comparable stages of competency, training and development 20,21,25,31. The classification suggested in this paper simplifies the current approaches and provides a clear picture of the minimum team capacities needed to deploy as an EMT, leaving space for the future design of pathways for those seeking sector professional development. As the three steps presented aim to be the minimum standard for education and training, no individuals should be deployed to the field without going through all steps; each being considered equally relevant for EMT performance during disasters. It is the responsibility of EMT organisations to ensure that staff has gone through all three steps. Well-trained EMTs will result in more effective performance and better care for populations affected, rather than just the career development of an individual.

Step 1 – Professional competence and license to practice

The core standards recommended within the 2013 publication ‘Classification and minimum standards for Foreign Medical Teams in sudden onset disasters’ 11 , already 7 underline the first step to consider in relation to EMT education and training: ‘FMTs must ensure all their staff are registered to practice in their home country and have licence for the work they are assigned to do during their deployment, as well as showing expertise in their field of practice’.

Although EMT organisations are not in charge of providing this education, they have the responsibility to ensure their staff have been trained and accredited by a competent authority for their field of health practice. This learning step must occur before a professional becomes part of the EMT. For example, an EMT member would comply with step 1 by getting a medical degree, a license to practice from their specific professional body and relevant working experience in his/her home country.

Step 2 – Adaptation to context

Another established core standard for EMTs 11 is the need to ensure members are appropriately trained for the context in which they will work. Step 2 of the recommended learning approach emphasises that EMT members must adapt exiting professional skills and competencies to the resource limited emergency contexts.

Step 2 training should be done well ahead of deployment. Courses and education platforms should besides professional context adaptation focus on developing skills to critically assess and analyse the situation in order to ensure that priority is given to the most essential health needs of the population and a capacity to triage, based on public health priorities and available resources. Examples of technical training courses are those providing context specific clinical skills (surgery, wound care, paediatrics, mass casualty), public health (disease prevention, health systems, management of epidemics) or logistics (shelter, water and sanitation). Examples of non-technical subjects include ethics, cultural awareness, leadership, communication or understanding of the humanitarian structure.

EMT organisations may have the capacity to facilitate this learning step internally, but can also use external partners, such as universities or training companies, to organise and deliver it to their EMT members. To receive step 2 education and training, 8 individuals could also enrol in existing university based Masters programmes or short courses related to disaster and emergency management or health in disasters.

Step 3 – Team performance

Previous professional expertise and the completion of emergency and low-resource adapted individual courses provide the basis for good practice in the field, but do not ensure the successful performance of a team deployed into a disaster 19.

EMT members need to prepare for their deployment as part of a multidisciplinary team integrated within an EMT deploying organisation. This training goes beyond the individually focused training of step 1 and 2 above, and puts teamwork and EMTs’ specific procedures into focus. All EMTs should offer pre-deployment courses in order to transfer to its members the values and mandate of the organisation, its main protocols, communication pathways, security guidelines, teamwork dynamics, basic aspects of personal health and travel, and other subjects related to deployment working and living conditions. This training must be practical and multidisciplinary, and inclusive of all health care workers and non-medical professions. It is anticipated that the team members who train together may not always be the same that deploy together; but a standardised pre-deployment course should allow those taken from an organisation’s roster to work as an effective team. Step 3 training is the responsibility of the EMT agency but may be delivered in partnership with other training providers.

2. Considerations for training delivery

From theory to practice

We assume both theoretical and practical learning to be a base for any professional field. In the initial phase, theoretical education facilitates knowledge acquisition, but soon trainees require more practical and hands-on training sessions in which to apply these theories. Following the same pattern, EMT learning process moves from theory to practice as deployment comes closer. Face-to-face or e-learning theoretical courses should then be followed by real or simulation based, practical training. Although it will be best to expose trainees to the real context of the disaster and emergency in which 9 they will ultimately be working, this is rarely possible. As an alternative, simulation based training can offer a feasible and effective approximation to real-life practice in the field 34,35,36.

The traditional real-life drills and table top exercises can be difficult to organise due to the length of time and amount of resources required for design, execution and review. Technologically based approaches to disaster training appear promising in their ability to bridge the gaps between other common training formats. For example, during the recent Ebola outbreak emergency, virtual reality (VR) training was designed by replicating an Ebola Treatment Centre (ETC) to create a safe and realistic environment in which trainees could gain realistic skills. Although it had some limitations, a VR training programme produced a cost-effective option and increased access to simulation training 37.

Although more costly, exposure of trainees to low-resource settings could be achieved through the establishment of field training facilities, similar to the Red Cross/ Red Crescent Field School included in table 2. Agreements between academic institutions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) can offer similar opportunities. An example of this was a project in which online training was combined with a medical apprenticeship in low-income countries during an anaesthesia and intensive care medicine residency in Italy 38.

From individual to team training

Although the pursuit of individual expertise is important, the scale of disaster operations requires an organised response by teams of interdependent members, who can incorporate individual efforts into coordinated actions 39. Thus, understanding the roles of other professional groups included in the team and learning how to work together to reach a common goal are key aspects of a successful disaster response 40. Moreover, team training across different clinical contexts has proven to impact positively upon healthcare teamwork processes and it has been associated with improvements in patient outcomes 41,42. The team approach is also valid for the whole system responding to the disaster – i.e. working as a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary team with national staff and other organisations.

While EMT training is mandatory it cannot replace experiential learning and field mentorship. The team composition should be considered carefully, with a balance between senior and junior staff that allows a quality performance of the team and the mentorship of its junior members. This is likely to be inappropriate in the first response team, but to be encouraged in second and subsequent staff rotations as a situation stabilises. This important recommendation is also recognised in the minimum standards for FMTs 11.

Just-in-time training

Just-in-time training (JITT) is recognised in medical education as a valuable and effective training method to disseminate newer concepts or seldom-performed procedures 43,44. Already suggested as relevant to EMT training 30, potential JITT modules will introduce additional skills and knowledge to the staff just before deploying into specific contexts – e.g. clinical management of Ebola patients or description of trauma national protocols of a disaster-affected country. JITT courses – short and well defined in their scope – could also be organised to present updates of former EMT guidelines and procedures, or refresh important concepts after a period without deploying to the field or since original pre/deployment training.

Skills mix and team composition

Training matrices can be used to identify which team members require which skills and to what depth of knowledge. The idea of team rather than individual skills development is important. A surgical team in a Type 2 facility for example must be able to perform emergency general surgical procedures such as a laparotomy for trauma, as well as wound and limb injury care that has orthopaedic and plastic surgical elements, and be able to manage an emergency caesarean section. In that case the organisation must decide to either bring a surgical team encompassing the different specialised surgeons or to bring generalist surgeons who have specific skills in each of these areas. Similarly all team members must be aware of safety and security procedures, but at least one person from the team should have in-depth knowledge of this area to support team safety and security planning and operations.

Need to complete all levels of training

Individuals or groups who were not self-sufficient in the field contributed to the chaos in recent disasters and added an inappropriate burden to the affected country without contributing to the care of the affected population. Academic institutions providing Step 2 education and training must guide their graduates on the appropriate mechanisms to deploy. If not there is a risk of encouraging more spontaneous and unsupported responders, in opposition to a systematic approach to emergency response led by wellprepared teams.

Recent EMT field deployments have exposed a lack of public health skills amongst some deployed clinical specialists, for instance during the Ebola outbreak, when public health understanding was especially relevant 45. This again reflects the need for a multidimensional learning framework in which contextual adaptation is crucial.

Next steps

The framework proposed in this paper – backed-up by international experts in the subject – encompasses existing successful initiatives where these principles have already been applied and documented in relation to EMT training, and complies with recognised WHO EMT standards. Although we believe this is a strong base for a global framework, its endorsement and testing by other EMT organizations should follow this publication.

This paper suggests the key components for an operational learning framework for EMTs but recommended curriculum content for each of its steps needs to be further defined and agreed. This should come with strong input from EMT organisations, rather than be driven solely by academic institutions. This could occur as a dedicated working group under the auspices of the WHO EMT initiative. The EMT WHO website could be used to share current education and training programmes by well-known organisations that could serve as guidance for other EMTs. Further development of open access training materials available to national and international EMTs will contribute to the quality improvement of the training practices.

Evaluation and accreditation of courses and participants remains an important area for discussion. The completion of exercises by trainees during a classroom course or a simulation exercise does not ensure they are competent to perform appropriately once in the field. Effective mechanisms to assess trainees´ capacities should be established. For example, training-participants’ performance during simulation exercises can be assessed through debriefing sessions, led by specialised facilitators who can challenge inadequate 12 practices identified and recommend improvements. Supervision and assessments during and after deployments can also contribute to the evaluation of the level of competence of EMT professionals once they are working within an organisation. Tools to allow meaningful and constructive debriefing and feedback from disaster affected countries also need to be developed. The establishment of a minimum dataset and uniform reporting, including collaborative and coordinated post-deployment research and evaluation, will strengthen the development of the learning framework.

Conclusions

Multiple attempts to standardise the education and training of disaster and emergency responders have been made; these focused mainly on an individual’s professional development rather than improved team operational performance. No agreed overarching framework currently guides EMTs through the principles of training or recommends suitable training methodologies. Since a systematic approach is needed, this report suggests a three-step operational learning framework for EMTs that could be implemented by EMT organizations globally. In addition, the importance of the training modalities used is highlighted; including individual and theory based education but emphasising team and practical simulations as crucial to the operational nature of an EMT’s work. Further work is required to fully develop an agreed curriculum and open access training materials for EMTs. These training materials will also contribute to the development of N-EMTs, some of which may be offered to neighbouring countries as IEMTs. WHO, EMT organisations, universities, professional bodies and training agencies can all contribute to the development of professional and highly functioning teams, but should recognise that only a collective approach will improve EMT field performance and crucially, result in better care for the victims of large scale health emergencies.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.

Corresponding Author

Ian Norton

Contact e-mail: [email protected]

The 2016 World Humanitarian Summit Report Card

The World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) in Istanbul took place on May 23-24, 2016 with 9000 attendees from humanitarian aid and disaster relief organizations, crisis-affected countries and governments. It was in part prompted by the terrific flow of refugees from the Middle East to Europe, the growing gap in being able to meet the needs of displaced peoples affected by conflict and disasters and the realization that broad reform is essential to move forward.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) conducted pre-WHS consultations with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academia, youth, and the private sector on 13 October 2015. This was followed by a global meeting on 14-16 Oct to capture the opinions, ideas and voices of the multitude of stakeholders. 1,2

OCHA attempted to attract a large number of global leaders to the summit with all indication of conducting a formal intergovernmental process. However, when only 50 non-G7 leaders indicated attendance,3 representing a paltry 5.2% of the global population, it may have determined that an ‘unofficial’ exploratory approach would be more useful in advancing the reform agenda at this stage in the process. Unfortunately, nation states prefer to participate when the outcomes are clear and may have felt disinclined to attend due to a lack of extensive political involvement and dialogue.4 However, the tightly orchestrated program left little room for exploration and emerging issues had to be discussed in casual conversation.

Based on the outcomes of the pre-WHS process and the resulting agenda and participant list, some decided not to attend. Most notable was the absence of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which was frustrated by the lack of attention to international humanitarian law and civilian protection – two issues that greatly affect its own ability to operate and function effectively in conflict-prone environments.5 In 2015, 150 health facilities had been bombed, and in Syria over 220 systematically targeted attacks were launched on separate medical facilities making a shambles of any “law of war” protections in the 21st Century.6 The inclusion of these elements was a reasonable expectation since the summit was oriented towards organizations engaged in humanitarian assistance, which needs to be bundled with legal and physical protection. Likewise, this neglect was a slight on cooperation with the security sector, which is invariably called upon for assistance as soon as governments and NGOs cannot cope. Clearly, today’s wars are pursued on the same barbaric belief last seen centuries ago: ‘the more egregiously and violent the war is waged the shorter it will be.’

Conflict results in displaced peoples crossing borders and subsequent international assistance. Much of what happens in humanitarian action is thus about politics and security, which requires the support of international law and the enforcement of accepted standards. Nevertheless, no clarity was forthcoming on the required conditions that must exist for a UN agency to initiate humanitarian action and exactly what relevance the Geneva Convention requirements have today. Without these issues of law being resolved, the protection of assisters and the assisted continues to be problematic.

The organizers made the best of the situation and abandoned the prospect of political solutions and serious reform in favor of smaller, more achievable objectives. The outcomes reflected this predicament and manifested in the form of many fairly technical commitments, such as the ‘Grand Bargain,’ the name given for a package of reforms to humanitarian funding designed to make humanitarian assistance more ‘effective and efficient.’ However, despite considerable attention to technical financial solutions, the reforms were accused of being watered down during the negotiation process. Not much emerged to fill the humanitarian aid gap or address the need for flexible multiyear financing and longer time-frames. It is hoped that efforts will now turn towards monitoring action and accountability to avoid depressing effects on the ground.