Introduction

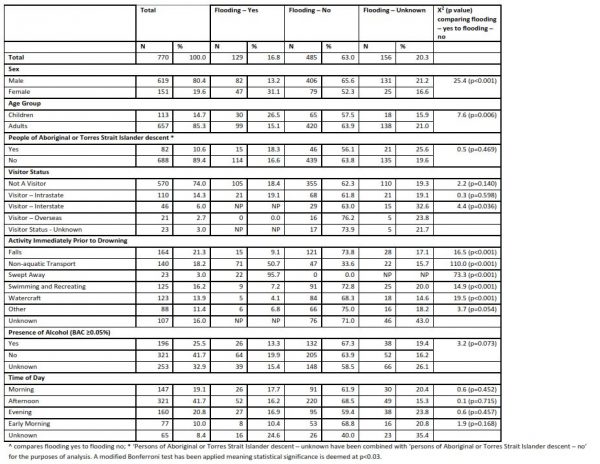

Flooding is a common natural disaster 1, leading all other natural disasters with respect to the number of people affected and in resultant economic losses 2. The Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) reported 164 floods claimed the lives of 4,731 people in 2016, with a further 77.8 million people affected 3. Drowning is a leading cause of death during times of flood 4, with floods estimated to have claimed the lives of over 500,000 people between 1980 and 2009 globally 5.

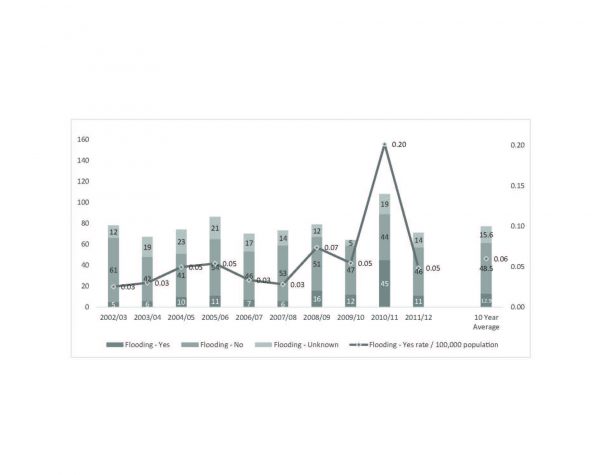

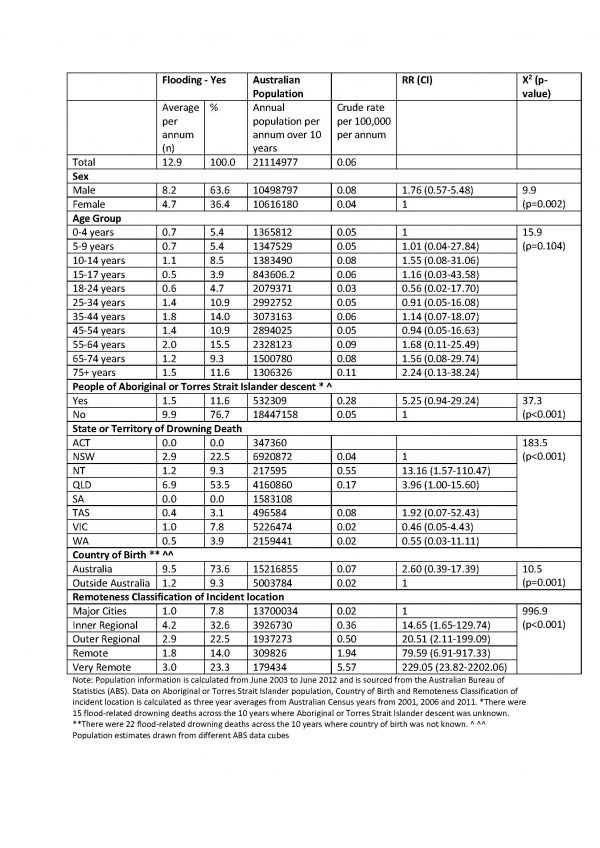

Rivers have been identified as a leading location for drowning internationally 5 and in Australia 6, and flooding is a known risk factor 7. Flooding results in the drowning deaths of 13 people, on average, per year in Australia 7.

Geographical remoteness (which includes isolation from major services such as medical assistance) is a risk factor for flood-related drowning in Australia 7. People in remote and very remote areas experience 80 and 229 times the risk respectively of drowning in a flood-related incident compared to major cities 7. An exploration of how to prevent drowning incidents during floods in rural and remote Australia is vital to reducing the risk and loss of life.

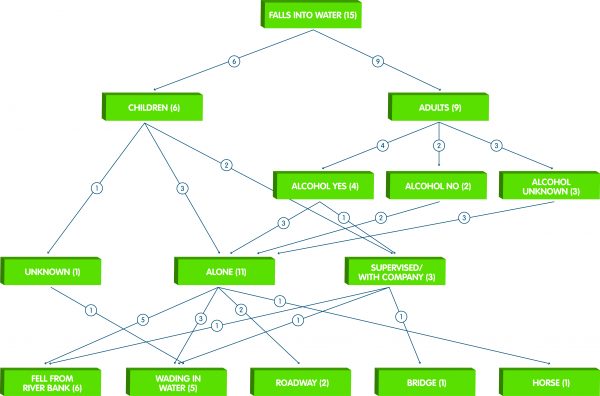

Driving through floodwaters is the leading activity prior to drowning in floodwaters, both in Australia 7,8 and internationally 9, 10. Recreational interaction with floodwaters, such as for swimming, also claims lives domestically in Australia 7, 11, as well as around the world 12, 13.

The need for systematic data collection for the prevention of loss of life during disasters has been identified, rather than data collected on an ad-hoc basis at the time of the emergency 10. To guide prevention efforts, including identifying those most at risk, this study aimed to survey river users on previous participation in two flood-related behaviours; driving through floodwaters and swimming in a flooded river.

Methods

A self-reported survey of adult river users (18 years and older) at four river locations was conducted in January and February 2018 (summer, school holidays, wet season), namely Alligator Creek in Queensland (classified as Outer Regional) and the Murrumbidgee (Inner Regional), Murray (Inner Regional) and Hawkesbury (Major Cities) rivers in New South Wales. Alligator Creek was located in a national park (no cost to enter), whereas the other three sites were on public land. All locations had BBQ facilities, public toilets and the Hawkesbury site featured a boat ramp. All locations were previously identified as blackspots for fatal drowning.

Potential respondents were randomly approached and asked to participate. Once informed consent was obtained, respondents were asked a range of demographic and river usage questions, as well as questions about knowledge of drowning risk factors and alcohol consumption questions. All river users who completed a survey were also breathalysed, whereby their blood alcohol content (BAC) was estimated by recording the alcohol on their expired breath 14. For analysis, the results of the breathalysing were classified as BAC positive yes/no (i.e. a BAC ≥0.001%) and BAC contributory yes/no (i.e. a BAC ≥0.05%).

The focus of this study is the self-reported flood-related behaviour of river users in Australia. Respondents were asked two questions on flood-related behaviour: ‘Have you ever driven through floodwaters?’ and ‘Have you ever swum in a flooded river?’ Respondents could answer yes or no. This study forms part of a wider study on river usage 15 and alcohol consumption 6, 16.

The survey was administered as both paper-based forms and online through SurveyGizmo (www.surveygizmo.com) using iPads. Those surveys completed on paper were then transferred into SurveyGizmo on the same day the paper-based survey was undertaken. The final dataset was downloaded from SurveyGizmo into IBM SPSS V20 for analysis. To check accuracy of data entry, every tenth paper-based survey (n=56) was checked (by authors AEP and RCF). This resulted in the checking of 56 x 34 questions, resulting in a 0.7% error rate. These errors were corrected prior to analysis.

In SPSS, remoteness classification of the respondent’s postcode was coded using the Australian Standard Geographical Classifications (ASGC) 17. Residential postcode was coded to its remoteness classification using the Doctor Locator website (www.doctorconnect.gov.au).

Residential postcode of the respondent was also coded to the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) 18. The Index is ranked from 1-10, with a low score indicating relatively greater disadvantage (e.g. many people with low incomes and many people in unskilled occupations), compared to a high score which indicates a relative lack of disadvantage. For ease of analysis, IRSAD was categorised as low (rank 1-3), high (rank 8-10) and other/unknown.

Univariate analysis was undertaken as was chi square analysis with a 95% confidence interval (p<0.05). Chi square analysis was run using yes or no for each flood-related behaviour. Chi square analysis excluded the unknown variable.

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the James Cook University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC – H7249).

Results

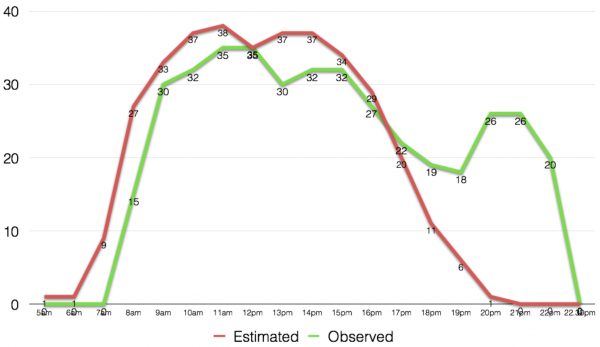

Of the 688 people surveyed, 98.3% (n=676) answered the question about driving through floodwaters and 98.0% (n=674) answered the swimming in a flooded river question. There were 35.7% of respondents who had driven through floodwaters. Males (43.9%) were more likely to have driven through floodwaters than females (27.8%) (X2=19.0; p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Figure 1: Two flood-related behaviours by sex of river users surveyed

People aged 75+ years (42.9%), 65-74 year olds (40.7%) reported the highest proportion of respondents, who had driven through floodwaters; however age group did not impact likelihood of having driven through floodwaters. (Table 1)

Please note the unknown variable was excluded from chi square analysis

Total

Driven through floodwaters – yes

Driven through floodwaters – no

X2 (p value)

N

%

N

%

N

%

Total

676

100.0

241

35.7

435

64.3

–

Sex

Male

326

48.1

143

43.9

183

56.1

18.969 (p<0.001)

Female

350

51.9

98

27.8

254

72.2

Age group

18-24 years

190

28.1

67

35.3

123

64.7

0.017 (p=0.895)

25-34 years

144

21.3

55

38.2

89

61.8

0.516 (p=0.473)

35-44 years

124

18.3

44

35.5

80

64.5

0.002 (p=0.966)

45-54 years

120

17.8

38

31.7

82

68.3

1.010 (p=0.315)

55-64 years

64

9.5

23

35.9

41

64.1

0.003 (p=0.960)

65-74 years

27

4.0

11

40.7

16

59.3

0.318 (p=0.573)

75+ years

7

1.0

3

42.9

4

57.1

0.160 (p=0.689)

Country of birth

Australia

571

84.5

216

37.8

355

62.2

7.598 (p=0.006)

Outside of Australia

105

15.5

25

23.8

80

76.2

Remoteness classification of residential postcode

Major Cities

123

18.2

34

27.9

89

73.0

4.906 (p=0.027)

Inner Regional

388

57.4

143

36.9

245

63.1

0.130 (p=0.718)

Outer Regional

136

20.1

58

42.6

78

57.4

2.999 (p=0.083)

Remote and Very Remote

6

0.9

2

33.3

4

66.7

0.023 (p=0.880)

Unknown

23

3.4

4

17.4

19

82.6

–

IRSAD classification of residential postcode

Low

117

17.3

42

35.9

75

64.1

0.877 (p=0.349)

High

113

16.7

34

30.1

79

69.9

Other/Unknown

446

66.0

165

37.0

281

63.0

–

Alcohol contributory (BAC ≥0.05%)

Yes

49

7.2

28

57.1

21

42.9

10.855 (p=0.001)

No

627

92.8

213

34.0

414

66.0

Respondents born in Australia were significantly more likely to have driven through floodwaters (37.8% yes; X2=7.6; p=0.006). Respondents residing in outer regional areas had the highest proportion of people driving through floodwaters (42.6%) compared to major cities (27.9%), with residents of major cities significantly less likely to have performed the behaviour (X2=4.9; p=0.027). Respondents classified as residing in low IRSAD areas reported a slightly higher proportion of respondents having driven through floodwaters (low 35.9%; high 30.1%). (Table 1)

Nineteen percent (19.2%) of those who self-reported having driven through floodwaters recorded a positive BAC reading, with 60.9% of those recording a BAC at contributory levels. Those who had driven through floodwaters were significantly more likely to record a BAC at contributory levels (X2=10.9; p=0.001). (Table 1)

Of all respondents to the swimming in a flooded river question, 18.7% stated they had swum in a flooded river. Males were significantly more likely to have swum in a flooded river (X2=26.5; p<0.001). Respondents aged 18-24 years were significantly more likely to self-report having ever swum in a flooded river (X2=17.9; p<0.001), while 45-54 year olds were significantly less likely to report having done so (X2=12.0; p=0.001). (Table 2)

Please note the unknown variable was excluded from chi square analysis.

Total

Swum in a flooded river – yes

Swum in a flooded river – no

X2 (p value)

N

%

N

%

N

%

Total

674

100.0

126

18.7

548

81.3

–

Sex

Male

326

48.4

87

26.7

239

73.3

26.537 (p<0.001)

Female

348

51.6

39

11.2

309

88.8

Age group

18-24 years

191

28.3

55

28.8

136

71.2

17.893 (<0.001)

25-34 years

143

21.2

33

23.1

110

76.9

2.294 (p=0.13)

35-44 years

124

18.4

18

14.5

106

85.5

1.745 (p=0.186)

45-54 years

120

17.8

9

7.5

111

92.5

12.036 (p=0.001)

55-64 years

63

9.3

6

9.5

57

90.5

3.845 (p=0.050)

65-74 years

26

3.9

2

7.7

24

92.3

2.154 (p=0.142)

75+ years

7

1.0

3

42.9

4

57.1

2.717 (p=0.099)

Country of birth

Australia

571

84.7

113

19.8

458

80.2

2.950 (p=0.086)

Outside of Australia

103

15.3

13

12.6

90

87.4

Remoteness classification of residential postcode

Major Cities

122

18.1

21

17.2

101

82.8

0.084 (p=0.772)

Inner Regional

388

57.6

54

13.9

334

86.1

11.462 (p=0.001)

Outer Regional

136

20.2

43

31.6

93

68.4

21.086 (p<0.001)

Remote and Very Remote

5

0.7

0

0.0

5

100.0

1.116 (p=0.291)

Unknown

23

3.4

8

34.8

15

65.2

–

IRSAD classification of residential postcode

Low

115

17.1

20

17.4

95

82.6

0.448 (p=0.503)

High

113

16.8

16

14.2

97

85.8

Unknown

446

66.2

90

20.2

356

79.8

–

Alcohol contributory (BAC ≥0.05%)

Yes

49

7.3

19

38.8

30

61.2

13.913 (p<0.001)

No

625

92.7

107

17.1

518

82.9

Inner regional dwelling respondents were significantly less likely to have swum in a flooded river (X2=11.5; p=0.001); whereas those residing in outer regional areas were significantly more likely to have done so (X2=21.1; p<0.001). Country of birth and IRSAD did not significantly impact likelihood of having swum in a flooded river. (Table 2)

Twenty-two percent (22.2%) of those who self-reported ever swimming in a flooded river recorded positive BAC readings when breathalysed. Of these, 67.9% recorded BACs at contributory levels. There was a statistically significant link between those who reported having swum in a flooded river and both positive BACs (X2=4.4; p=0.037) and BACs at contributory levels (X2=13.9;p<0.001). (Table 2)

Discussion

Flooding is one of the most deadly, and costly, of all natural disasters 2, 3, the frequency of which is likely to increase due to climate change 19. Minimising the impact of such disasters, including people’s interaction with floodwaters, will reduce loss of life. This study found that 36% of river users surveyed had driven through floodwaters and 19% had swum in a flooded river. Both activities were more common among males, with 18-24 year olds and people residing in outer regional areas significantly more likely to report having swum in a flooded river. There was a statistically significant link found between respondents who self-reported having participated in both risk flood-related behaviours and recording BACs at contributory levels when breathalysed at the river.

The movement of people during floods is a challenge for those living in rural Australia. Previous research 20, 21,22, 23 exploring factors impacting driving through and avoiding driving through floodwaters, has highlighted the issue of fatigue, a particularly important factor as an alternate route can add significant time to a journey and thus tempt drivers to cross flooded roads 20. Reduced investment in infrastructure such as bridges in regional and remote areas 24 may also contribute to an increased need to drive through floodwaters.

Simply discouraging people from driving through floodwaters is unlikely to be practical in rural Australia, particularly in areas with regular low-level flooding. More effective prevention strategies may include improved education on when it is safe to drive through (low depth, still water, stable road base) and when it is not (e.g. deep water, moving water and unstable road base). However there are challenges in identifying a stable road base and current prevention messages take a didactic approach advising “If it’s flooded, forget it” (https://floodwatersafety.initiatives.qld.gov.au/) and not to drive through.

Outer regional residents were found to have the highest proportion of respondents who self-reported having ever driven through floodwaters, as well as being significantly more likely to have previously swum in a flooded river. This may be due to the lack of infrastructure, lower initial awareness of the risk or over-familiarity with flooding leading to an underestimation of the risk. The link between participation in risky flood-related behaviours and outer regional residents requires further investigation.

Internationally, males are overrepresented in drowning statistics 5, accounting for 80% of fatal drownings overall, and fatal river drowning in Australia 6. Males have been identified as having poorer swimming skills 25 and lower levels of water safety knowledge than their female peers 26, as well as being more prone to risk-taking behaviour 27, 28. However, this proportion is higher than the proportion of 60% male for flood-related fatalities due to driving through floodwaters 7, although it reflects the number of people reporting in this study (i.e. the 59% of male respondents to this survey who reported having driven through floodwaters). Thus highlighting that the risk is about exposure (i.e. driving through floodwaters) rather than related to the sex of the person who drowns. While different messaging for each sex may be appropriate for the effective delivery of prevention messages, there is a need for strategies to mitigate the likelihood of people driving through floodwaters targeted at flood-prone locations, regardless of gender.

Although age was not found to be a statistically significant indicator of likelihood of having driven through floodwaters, respondents in the oldest age groups recorded the highest proportion of respondents who had undertaken the activity, with 43% of 75+ year olds and 41% of 65-74 year olds self-reporting having driven through floodwaters. As the questionnaire did not define a timeframe within which to have performed the activity (i.e. had the respondent ever driven through floodwaters), this may reflect a relatively greater number of flood seasons through which the respondent has lived and therefore, had the opportunity to drive through floodwaters, rather than any riskier behaviour being undertaken by the older age group. Further research may be warranted exploring attitudes towards driving through floodwaters among the older age group.

This study identified one in five respondents had swum in a flooded river. Unlike driving through floodwaters where as people aged, the likelihood of driving through floodwater increased (greater chance of encountering floodwater), young people (18-24 years) were more likely to report swimming in a flooded river. This dichotomy may suggest an element of risk-taking in youth, however this appears to be a recent activity, as older people were less likely to report swimming in floodwaters. Swimming in floodwaters is a poorly understood behaviour with little previous research. The survey tool did not examine the context within which the respondent had swum in a flooded river (e.g. out of necessity, skylarking or performing a rescue). Further research should examine the reasons behind this behaviour. With those residing in outer regional areas found to be more likely to have swum in a flooded river, prevention strategies must take into account the regional and remote context 29.

Alcohol is a known risk factor for drowning and aquatic-related injury 30. This study identified a statistically significant link between alcohol consumption, in particular respondents recording BACs at contributory levels, and self-reported participation in both risky flood-related behaviours being analysed. While the survey questionnaire did not ask if the respondent was under the influence of alcohol at the time of participating in these risky flood-related behaviours, it may be that alcohol contributes to a person’s decision to take risks in and around floodwaters. This is worthy of further research to better understand the motivations underlying a person’s decision to interact with floodwaters in such a way. Such information will add a helpful layer to the development of preventative messaging and campaigns 23.

As with all self-reported surveys there are limitations. These include recall bias, the survey being administered in English and the survey not defining what was meant by floodwaters (for driving through) or a flooded river (for swimming). Respondent were asked if they had ‘ever’ undertaken the two flood-related behaviours, and as such caution should be used when interpreting the age group analysis as the age at which the behaviours were performed was not captured. This study did not examine frequency of the behaviours undertaken. This was a cross-sectional study and does not determine cause and effect. The sample was a random convenience sample and therefore results represent the views of those attending the four river locations only. The survey was administered in the summer and wet season months and may impact recall. Refusals were not recorded.

Conclusion

Preventing drowning in floodwaters is an international challenge, made more difficult by people driving through, or swimming in, floodwaters. Practical strategies to reduce loss of life due to driving through floodwaters are required, including skills to assess the risk and make informed decisions on when it is safe to drive through and when it is not. Swimming in floodwaters is a little researched topic. While this study has identified one in five people have undertaken the behaviour, commonly at a young age, there is a need for further research to understand the context of the behaviour and the motivations for engaging in it, including the role of alcohol. Such knowledge would allow for effective, regionally-specific drowning prevention strategies to be developed, targeting those most at-risk, in order to reduce loss of life during times of flood.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical constraints imposed by the Ethics Committee that granted approval for this study, the data is unable to be publicly uploaded. Data requests can be made by contacting [email protected] and quoting the ethics approval number H7249.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Corresponding Author

Amy Peden, Royal Life Saving Society – Australia and James Cook University ([email protected])

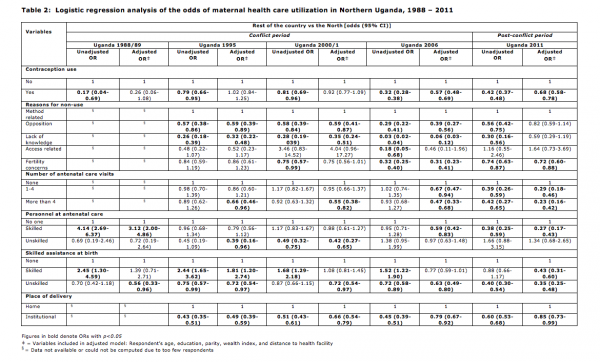

Methods: PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library were searched from September, 2001 through July, 2016. Reviewers identified eligible studies and synthesized odds ratios (ORs) using a random-effects model.

Results: The meta-analysis included findings from 7 studies (29,930 total subjects). After adjusting for multiple comparisons, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with minority race/ethnicity (OR, 1.40; 99.5% Confidence Interval [CI], 1.04 to 1.88), lower income level (OR, 1.25; 99.5% CI, 1.09 to 1.43), post-9/11 social isolation (OR, 1.68; 99.5% CI, 1.13 to 2.49), post-9/11 change in employment (OR, 2.06; 99.5% CI, 1.30 to 3.26), not being married post-9/11 (OR, 1.59; 99.5% CI, 1.18 to 2.15), and knowing someone injured or killed (OR, 2.02; 99.5% CI, 1.42 to 2.89). Depressive symptoms were not significantly associated with greater age (OR, 0.86; 99.5% CI, 0.70 to 1.05), no college degree (OR, 1.32; 99.5% CI, 0.96 to 1.83), female sex (OR, 1.24; 99.5% CI, 0.98 to 1.59), or direct exposure to WTC related traumatic events (OR, 1.26; 99.5% CI, 0.69 to 2.30).

Discussion: Findings from this study suggest that lack of post-disaster social capital was most strongly associated with depressive symptoms among the civilian population after the 9/11 WTC terrorist attacks, followed by bereavement and lower socioeconomic status. These risk factors should be identified among civilians in future disaster response efforts.

]]>Introduction

The mental health consequences of the September 11, 2001 (9/11) World Trade Center (WTC) terrorist attacks in New York City (NYC) have been the focus of a substantial number of research endeavors over the past 15 years.1 A majority of this research has documented the etiology, prevalence, treatment, and risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in particular, as PTSD is reported to be the most common post-disaster associated condition.2 According to the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), PTSD is a conditional disorder that can develop among individuals after a qualifying trauma exposure.3 Qualifying trauma exposure must result from directly experiencing a traumatic event, being an eyewitness to trauma as it occurred to others, learning that a close associate suffered from a traumatic event, or experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of a traumatic event.3

Probable depression is another commonly studied post-disaster mental health outcome. Probable depression refers to a positive screen on a depression symptom screening instrument, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire.4,5 PTSD and probable depression among trauma-exposed groups of the WTC terrorist attacks have been thoroughly described.6,7,8,9,10 Examples of frequently studied trauma exposed groups include firefighters, police, emergency medical technicians, first responders, and recovery and cleanup workers.

In contrast to trauma-exposed groups, the general civilian population of NYC, comprised of survivors, NYC residents, people working in the area, and passers-by on the day of the attacks, is an example of a mixed-exposure group. After the WTC terrorist attacks, members of the civilian population suffered from varying levels of exposure to trauma. Many of these exposures may have not met DSM-5 trauma exposure criteria.11,12 The general civilian population is not always included in studies of prevalence estimates and risk factors for post-disaster PTSD and probable depression because disaster mental health research is typically interested in understanding mental disorders in relation to trauma exposure.13 In particular, comprehensive analyses of post-disaster probable depression among civilians are lacking in the literature.

The unpredictable nature of terrorist attacks have introduced new definitions of affected populations in disaster mental health research, as the purpose of terrorism is to invoke fear and anxiety among civilians in general.14 Moreover, probable depression is not dependent on qualifying trauma exposure, so the population susceptible to probable depression after a disaster such as a terrorist attack is larger than the population susceptible to PTSD.5 Carefully identifying risk factors for probable depression among the civilian population that were associated with the 9/11 WTC terrorist attacks may better inform future disaster preparation efforts.

Over the past 15 years, a number of studies have screened for probable depression among affected populations and stratified their analysis of trauma-exposed groups and civilians, or sampled cohorts of civilians specifically.15,16,17,18,19,20,21 The aim of this study was to synthesize the results from research on 9/11-affected survivors, residents, and passers-by, summarize the influence of probable depression among these cohorts, and evaluate the associations between probable depression and various risk factors.

Methods

Search Strategy

We conducted a meta-analysis following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.22 PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library were searched without language restriction from September, 2001 through July, 2016. Search terms included “World Trade Center”, “WTC”, “World Trade Center Disaster”, “WTCD”, “September 11”, “9/11”, “Depression”, “Major Depression”, “Probable Depression”, and “Mental Health” in various relevant combinations. Both published and unpublished sources of data were considered. References of studies and review articles were also manually searched to yield additional studies not found through the original search.

Study Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Two reviewers (A.C., and S.B.) screened the search results for eligibility. Disagreements between reviewers regarding the inclusion or exclusion of a study were resolved by a third reviewer (J.P.). Studies were eligible based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) original research article; 2) focused on the effects of the WTC terrorist attacks; 3) focused on adult populations based on age at the time of interview; 4) focused on civilians or reported separate analysis of civilians; 5) screened for depression using validated diagnostic criteria; 6) documented probable depression prevalence (number of patients in the cohort screening positive for depressive symptoms) or odds ratio (OR) among civilians in response to pre-defined risk factors; and 7) conducted within the NYC metropolitan area.

Data Extraction

Reported risk factors for probable depression were extracted and compared across studies. Our main exposure variables consisted of only risk factors that were similarly defined among at least two studies included in the meta-analysis. Probable depression prevalence, ORs, and standard errors corresponding to each risk factor were then extracted from each study. Our primary outcome was the OR for the association between the development of depression symptomatology and each risk factor. All ordinal and categorical risk factor variables were dichotomized to simplify outcome synthesis; the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method was used to evaluate ORs based on probable depression prevalence among combined groups and Woolf’s method was used to combine weighted averages of log ORs.23,24 Other data elements that were extracted from each article were author surname, publication year, inclusion criteria, method and time period of cohort recruitment, sample size, baseline demographic characteristics of the sample, and overall prevalence of depressive symptoms.

Statistical Analysis

We used the DerSimonian and Laird (DL) random-effects model25 to calculate pooled ORs and corresponding standard errors for each included risk factor. These pooled estimates were interpreted as summary effect sizes that expressed the common odds of screening positive for probable depression with the presence of a risk factor, versus absence of a risk factor. Weights were calculated by the inverse variance method.

Heterogeneity across studies was investigated by the Cochran Q test and measured using I² and H² statistics. We interpreted I² values of 0-25%, 26-50%, 51-75%, and 76-100% as unimportant, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively.26 Publication bias was evaluated visually by examining symmetry in funnel plots. Egger regression27 and the Begg-Mazumdar test28 were used to quantify asymmetry by providing an estimate of correlations between effect sizes and corresponding variances. All analyses were performed using R software version 3.2.3 with the metafor package.29

We conducted sensitivity analysis by stratifying studies by the type of diagnostic criteria used and the recruitment period midpoint. This allowed us to evaluate whether structured diagnostic interviews and symptom screening instruments yielded different findings, and whether more recent event exposure had a stronger influence on depressive symptoms. Prevalence estimates were weighted for the sample size of each study within a particular strata and averaged. Variance weighted least squares regression was used to test for temporal trend. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted by assessing how responsive our summary measures were to individual data. We repeatedly fit the DL model for each risk factor while censoring one study at a time.30

To account for multiple tests, corresponding to the number of risk factors identified, we applied the Bonferroni correction31 to adjust the width of our confidence intervals (CIs) while testing for significance. Associations were considered significant at an α = 0.05/10 = 0.005 level.

Results

Electronic Search and Selection of Studies

We screened 2,103 search results and excluded 2,058 articles on the basis of their titles or abstracts for not being WTC related, not being an original research article, or not investigating depression symptomatology (Figure 1). We then identified 5 additional studies after screening references of reviews. Of the remaining 50 studies, 43 were excluded for using self-reported prior diagnosis or unclear screening measures of depression (n = 7), not reporting sufficient data that could be pooled for analysis (n = 11), focusing solely on responders or not separating civilians in their analysis (n = 19), using a sample that overlapped with another study and reported the same risk factors (n = 5), or not being conducted within the NYC metro area (n = 1). The remaining seven studies met the inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis.

Fig. 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection

Study Characteristics

The 7 studies included were prospective cohort studies of civilians with sample sizes ranging from n = 149 to n = 22,026 (Table 1). Each study cohort was recruited independently from the civilian population, making the possibility of subjects participating in multiple studies, or overlap in the samples, unlikely. Study cohorts were also recruited at different times, and the mid-point of their recruitment periods were on average 2.94 years post 9/11.

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Studies that Satisfied the Inclusion Criteria

Across studies, the average age of subjects at the time they were interviewed was 44.5 years, 61% were non-Hispanic white, and 54% were female. Probable depression prevalence ranged from 9.4% to 31.0%, and the overall prevalence was 15.9%. Of the 7 studies, 4 used a full Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), which is considered the gold standard for diagnosing Major Depressive Disorder.32 The remaining studies used screening instruments to identify depression symptomatology, which is why we refer to our outcome as “probable depression” rather than as “clinically diagnosed depression”. The three studies reporting probable depression all used different screening instruments. Results from Caramanica et al. were adapted using Wave 3 of the WTC Health Registry,16,20 which used the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), applying a cutoff at scores ≥ 10. This criteria has been shown to have sensitivity = 0.99 and specificity = 0.92 relative to SCID.33 Boscarino et al.17 used the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18), which has been shown to have sensitivity = 0.71 and specificity = 0.87,34 and Neria et al.18 used the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME MD) Questionnaire, which has been shown to have sensitivity = 0.85 and specificity = 0.75,35 all relative to structured clinical interviews.

Identification of Risk Factors

There were 10 risk factors that were reported in more than one study. These 10 risk factors were divided into 3 categories: baseline demographic characteristics, post-disaster attributes, and exposure characteristics. Demographic characteristics included greater age, female sex, minority race/ethnicity (non-white or Hispanic/Latino ethnicity), no college degree, and lower income level. Post-disaster attributes included post-9/11 social isolation, post-9/11 change in employment status, and not being married post-9/11 at the time of interview. Exposure characteristics included knowing someone injured or killed during the attacks and direct exposure to 9/11 traumatic events.

Not all risk factors were defined identically in each study. No college degree, minority race/ethnicity, post 9/11 social isolation, not being married post-9/11, and direct exposure were reported both as multilevel categorical variables and as dichotomous variables comparing the presence of a risk factor to its absence. To facilitate pooling together these results, multi-level variables were dichotomized.

Association between Probable Depression and Risk Factors

Among the baseline demographic risk factors, only minority race/ethnicity (OR, 1.40; 99.5% CI, 1.04 to 1.88) and lower income level (OR, 1.25; 99.5% CI, 1.09 to 1.43) were significantly associated with elevated odds of probable depression (Figure 2). The pooled ORs for greater age (OR, 0.86; 99.5% CI, 0.70 to 1.05), female sex (OR, 1.24; 99.5% CI, 0.98 to 1.59), and no college degree (OR, 1.32; 99.5% CI, 0.96 to 1.83) indicated that these risk factors were not significantly associated with odds of probable depression.

Fig. 2: Forest Plot of Odds Ratios Stratified by Risk Factor.

All three post-disaster attributes (social isolation, change in employment, and not being married) were significantly associated with elevated odds of probable depression, and their pooled ORs were among the largest summary effect sizes of the ten evaluated. The largest effect size in this category was the pooled OR for post-9/11 change in employment status (OR, 2.06; 99.5% CI, 1.30 to 3.26). The second largest effect size in this category was the pooled OR for social isolation (OR, 1.68; 99.5% CI, 1.13 to 2.49), and the smallest effect size was the pooled OR for not being married post-9/11 (OR, 1.59; 99.5% CI, 1.18 to 2.15).

Knowing someone injured or killed by the attacks and direct exposure to traumatic events were classified as exposure characteristics. The former significantly increased odds of probable depression (OR, 2.02; 99.5% CI, 1.42 to 2.89) while the latter was not significantly associated with probable depression (OR, 1.26; 99.5% CI, 0.69 to 2.30).

Sensitivity Analysis for Diagnostic Criteria, Time from Disaster, and Removal of Individual Data

Out of the 7 studies included, 4 used full structured diagnostic interviews and 3 used symptom screening instruments. Studies using symptom screeners detected higher rates of probable depression prevalence (Table 2). All associations for risk factors that were statistically significant in the primary analysis remained statistically significant in both sub-groups of diagnostic criteria. Additionally, while the magnitude of the estimates remained comparable, in the sensitivity analysis female sex was a significant risk factor based on structured interviews, and lack of college degree and direct exposure were significant risk factors among studies that used symptom screeners.

Table 2: Study Outcomes Stratified by Type of Diagnostic Instruments Used

We evaluated the prevalence of probable depression among all civilians included in studies that conducted interviews (midpoint of interview period) within a particular year (Supplementary Table). Although there were few studies included for each year, there was no significant temporal trend in depression prevalence (P = 0.25). We also assessed how stable our results were by evaluating the DL model for each risk factor after removing one study at a time (Table 3). This was only conducted for risk factors where results from more than two studies were synthesized. The female sex, minority race/ethnicity, no college degree, lower income level, and not being married post 9/11 risk factors lost or gained significance after removal of an individual study, however, all point estimates remained within the 95% confidence intervals of the original pooled estimates.

Table 3: Leave-One-Out Sensitivity Analysis for Each Risk Factor

Publication Bias

Visual inspection of funnel plots for each risk factor and for all studies combined did not reveal any notable publication bias (Supplementary Figures 1 & 2). Additionally, neither the Begg-Mazumdar rank correlation test (Kendall’s τ = 0.19, P = 0.10) nor the Egger regression test (z = 1.06, P = 0.29) detected statistically significant publication bias, although it is possible that the small number of included studies limits the power of this test.

Discussion

This study draws attention to probable depression after the 9/11 WTC terrorist attacks among civilians in the NYC metro area. We meta-analyzed effect sizes for various factors associated with probable depression from studies conducted over the past 15 years. Our analysis identified baseline demographic characteristics, exposure types to the WTC terrorist attacks, and post-disaster attributes, and quantified their association with post-9/11 probable depression.

The prevalence of probable depression varied considerably across studies included in our meta-analysis. This can partly be attributed to differences in the characteristics of each cohort and the type of diagnostic criteria employed. We observed disparities between results yielded by symptom screening instruments and full structured diagnostic interviews that could have implications for future studies of post-disaster probable depression. Symptom screening instruments, which generally have high sensitivity for diagnosis of major depression,33,34,35 detected higher rates of overall probable depression prevalence (16.6%) compared to full structured diagnostic interviews (11.7%). Moreover, although all risk factors that were significantly associated with probable depression in the primary analysis remained significant in the sensitivity analysis, the associations for some risk factors, including female sex, no college degree, and direct exposure, were not consistent across diagnostic criteria. The magnitude of these differences were small, however, and can partially be explained by high heterogeneity or lack of power since just two studies were present in subgroups that were inconsistent with the primary analysis.

Of the baseline demographic characteristics that we evaluated, only being of a minority race/ethnicity and earning lower income were significantly associated with elevated odds of probable depression. Since race/ethnicity and income are known to correlate with socioeconomic status,36 our results may indicate an important association between post-disaster socioeconomic status and elevated risk of probable depression after a terrorist attack among civilians. Minority race/ethnicity has also been reported to be a risk factor for probable PTSD and depression among responders.6,7,8 Taken together, lower socioeconomic status could be used to identify target populations of mental health interventions so that the effect of intervention is maximized.

We also evaluated the association between WTC terrorist attack-related experiences and probable depression by focusing on two types of exposures: direct exposure to trauma, or knowing someone killed or injured by the attacks. Suffering the latter did not require being physically present in the vicinity of the attacks while they occurred, however, it was still significantly associated with elevated odds of probable depression. This finding strengthens evidence that probable depression may not be geographically constrained to the area affected after a disaster,13 and that bereavement may play an important role in driving the development of probable depression associated with terrorist attacks.18 Furthermore, the finding that direct exposure to 9/11 trauma was not significantly associated with elevated odds of probable depression suggests that terrorist attacks that expose few civilians directly to trauma may still lead to meaningful community-wide depressive symptoms.

An important limitation surrounding our discussion of the association between trauma exposure and probable depression is the definition of traumatic exposure that each study used. The studies included in this meta-analysis mainly found that traumatic exposure was not significantly associated with elevated odds of probable depression, but studies that used lenient definitions of what constituted trauma may have underestimated this association. We found, however, that the North et al.13 study used the most stringent definition of exposure to trauma, using “careful categorization of 9/11 trauma exposures based on the DSM-IV-TR definition,” and still did not find a significant association between exposure to trauma and elevated odds of probable depression. As categorization of trauma became more careful and strict among the studies included in this meta-analysis, the effect size for its association with probable depression did not increase. Therefore, it is difficult to argue that inconsistent criteria for what constituted trauma in different studies explains the lack of association with elevated odds of probable depression observed.

We also classified social isolation, post-9/11 change in employment status, and not being married post-9/11 as post-disaster attributes and identified their association with probable depression. Social support is the perception that one belongs to a supportive social network and has access to a variety of social integration sources.37 In the studies we encountered, social support was reported as the perceived number of social integration sources and was variably categorized. Our results suggest that a lack of social support, or social isolation, may play an important role in the development of probable depression after a terrorist attack; civilians without social support suffered 68% increased odds of probable depression after the WTC terrorist attacks. Similar results were observed for post-9/11 change in employment status and not being married post-9/11 as risk factors. The magnitudes of the pooled ORs for these three risk factors were among the four largest of the ten summary effect sizes evaluated in our study. Social integration resources, employment, and marriage are pivotal forms of social capital that influence how psychological stress affects civilians.38 We found that access to these resources generally had a stronger association with probable depression than exposure or baseline demographics after the 9/11 WTC terrorist attacks. The causal direction of this association, however, remains uncertain as social capital and probable depression were both measured at the same time in the studies included.

These results must also be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. Primarily, we could not include pre-existing psychopathology as a risk factor due to large inconsistencies in how studies addressed it when reported. Pre-existing psychopathology has been strongly associated with post-disaster depression and other mental health outcomes.5,30 Its exclusion is not intended to undermine the need to consistently identify, screen, and triage patients with pre-existing mental disorders requiring treatment after a disaster such as a terrorist attack. Second, we could not consistently adjust for several confounding factors, such as prior trauma, when calculating ORs from reported data in the included studies. Some studies adjusted for covariates and provided adjusted ORs, but these adjustments may vary for the included studies. Third, there was between-study variability in the time of cohort recruitment and questionnaire administration. Although we evaluated the influence of more recent event exposure in a sensitivity analysis and could not discern a significant trend in depression prevalence among cohorts with less recent event exposure, there may have been unaccounted confounding with cohort characteristics and specific risk factors. Fourth, we observed high heterogeneity in specific subgroups when calculating pooled ORs. This may stem from individual variation in the effect of the risk factor, but it also may be caused by variation in the original classification of risk factors among different studies. Being able to differentiate between the influence of being a direct eyewitness to trauma and being physically harmed during the events would have been useful in this context. Differentiating between changes in employment status that were related to the WTC terrorist attacks, versus changes in employment status that occurred for other reasons, is another example of how having more specific classification of risk factors in different studies may have strengthened our analysis.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis identified risk factors for probable depression associated with the WTC terrorist attacks among mixed-exposure groups from the civilian population in the NYC metro area that was not directly involved in rescue or recovery efforts. We found that social isolation, change in employment, and not being married after the WTC terrorist attacks were three of the four most strongly associated risk factors for probable depression. Furthermore, we found that direct exposure to WTC related traumatic events was not significantly associated with probable depression, while knowing someone injured or killed by the attacks was. Knowing someone injured or killed was the second most strongly associated risk factor for probable depression in this meta-analysis, suggesting that probable depression among civilians after a terrorist attack may primarily be bereavement driven. Finally, we identified minority race/ethnicity and lower income as the only baseline demographic characteristics that predicted elevated odds of probable depression. This association suggests that further efforts are necessary to understand and address the influence of socioeconomic status and probable depression among civilians after terrorist attacks.

Our analysis allows for a better understanding of the associations between probable depression and risk factors among civilians who were not involved in rescue or recovery efforts by providing quantitative estimates for each association. The strong association between lack of social capital and depressive symptoms suggests that monitoring employment status and the availability of support should be points of focus in future studies and intervention efforts. We further recommend that persons of lower socioeconomic status or difficulties coping with bereavement receive greater attention, irrespective of exposure to trauma, after terrorist attacks. These efforts could improve the efficiency at which high-risk persons from the civilian population are identified in future mental health interventions and disaster response efforts.

Corresponding Author

Abhinaba Chatterjee

Department of Healthcare Policy and Research

Weill Cornell Medicine

402 E 67th St

New York NY, USA 10065

Email: [email protected]

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 MH105384. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Data Availability

All relevant data are reported in the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This analysis used only de-identified, publicly available, and previously published data sources. The need for informed patient consent was waived by the institutional review board and ethical committee at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Appendix

Supplemental Figure 1. Funnel plot of all effect sizes extracted from studies included.

Supplemental Figure 2. Funnel plots of effect sizes for each risk factor.

Supplemental Table. Temporal Trend in Prevalence of Probable Depression.

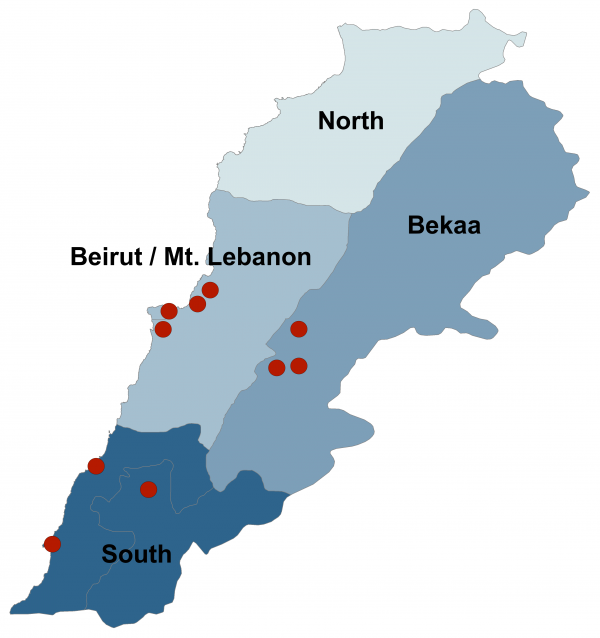

Methods. A survey of accessible areas, which were largely urban and government controlled, was undertaken from April - June 2016 to identify unmet needs and assistance priorities. A cluster design with probability sampling was used to attain a final sample of 2,405 households from ten of fourteen governorates; 31 of 65 (47.7%) districts were included that are home to 38.1% of people in need (PiN).

Results. Overall 45% of households received assistance in the preceding month; receipt of aid was lowest in al-Hasakeh (17%). Shelter was a concern, with 48% of households having shelter need(s); the unmet shelter needs were highest in the West Coast, Rif Damascus and al-Hasakeh. Food security was a major concern where 64% had unmet food needs and 65% at least one indicator of concern; food insecurity was most severe in Rif Damascus and the West Coast. Water was also a concern with 36% of households reporting inconsistent access and 48% no access to water for several day periods; water needs were highest in Aleppo.

Discussion. This assessment included accessible populations in predominantly urban and government controlled areas, which are likely to have better access to services and fewer needs than populations in rural locations or areas not controlled by the government. The humanitarian situation in inaccessible and non-government controlled areas is likely to be considerably worse, thus findings should not be generalized. An expanded humanitarian response is desperately needed for Syrians to better endure the conflict.

]]>Introduction

With an estimated 13.5 million people in need (PiN) of humanitarian assistance and 6.6 million internally displaced people (IDPs), Syria is the country with the world’s largest IDP population and among the most severe ongoing emergencies.1,2 At the start of 2016, of the 13.5 million PiN, 6.5 million (48%) resided in areas controlled by the Government of Syria, 4.5 million PiN were in hard-to-reach areas, and an estimated 8.7 million people had acute needs across multiple sectors.2 Humanitarian needs are ever-increasing while an inability to maintain humanitarian corridors and ceasefires continue to limit assistance to populations in areas where needs are greatest.3,4 Many needs remain unmet, and if assistance is provided, it is often insufficient in terms coverage or quantities distributed; for those with multiple needs, assistance may be received in one sector whilst other needs remain unaddressed.5,6,7

The 2016 Syria Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) set out three guiding objectives for the humanitarian response: (i) saving lives and alleviating suffering, (ii) enhancing protection, and (iii) building resilience.8 While the operational challenges to implementing a widespread response in an environment with poor security and access limitations are well known, financing is another less discussed barrier; only 33% of the nearly US$ 3.5 million needed to fund the 2016 Syria HRP is pledged.2,9 In light of the protracted nature of the conflict, immense humanitarian needs, and dearth of large-scale data, this assessment was undertaken to characterize unmet needs and inform humanitarian response in government controlled areas of Syria.

Methods

Sample size calculations were based on objectives of identifying unmet needs and assistance priorities and used the most conservative prevalence rate (50%), 80% power (1-β), and design effect of 1.5. A minimum sample of 1600, which allowed for ±3% precision, was increased to 2400 to provide increased power for regional comparisons. Few consistently reported and reliable population figures are available for Syria. A stratified multi-stage cluster design with probability proportional to size sampling was used, both because of challenges in attaining accurate population data and of the desire for region-specific estimates and comparisons. Accessible areas were divided into seven survey areas with, to the extent possible, PiN of similar size.

A 120 cluster x 20 household design was used; clusters were allocated using a stratified approach, where areas with larger PiN were assigned 20 clusters and smaller PiN 10 clusters to allow for similar probability of selection across areas. Within each area, clusters were assigned proportionally at district and sub-district levels using recent population data from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs which was perceived to be most reliable.10 The assessment incorporated ten of fourteen governorates (Deir-ez-Zor, ar-Raqqa, Idleb, and Quneitra were not accessible), however, not all areas of included governorates were accessible (Table 1).11In total, 31 of 65 (47.7%) districts were included that are home to 38.1% of PiN and a population of 4.1 million.2 Accessible areas were predominantly urban city centers (60%) with fewer clusters in peri-urban areas/remote cities (21%) and rural areas (19%). This distribution is reflective of the predominantly urban population (70%), high levels of urban need, and resulting urban-focused humanitarian response.8

Table 1. Overview of the Syrian Crisis, Affected Population and Assessment Coverage Areas

ARC GIS was used to identify random start points within sub-districts; those in unpopulated areas when reviewing Google Earth imagery were excluded. In developed areas, the nearest intersection, usually within 0.5km, served as the start point; the field team then reviewed start points to ensure accessibility. Every third household in several directions was sampled; replacement sampling was used and no more than two households within an apartment building were included. Back up coordinates were provided and an alternate start point used in the event that planned location was insecure.

To the extent possible, existing content from instruments used with Syrian populations was adapted to improve validity and comparability.1112,13,14,15,16 Pilot testing was conducted with Syrian refugees in Lebanon and in Damascus to ensure appropriateness of content and translation. A Training-of-Trainers approach was used where team leaders and study coordinators received five days of training in Lebanon; they later oversaw two days of interviewer training in their respective survey areas. Most interviewers and all team leaders had prior experience conducting humanitarian assessments in Syria.

The assessment was conducted between April and June 2016 by a US-Based international non-governmental organization (iNGO) and a Syrian partner with training and remote support from Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (JHSPH). Interviews ranged from 20 to 45 minutes. To protect anonymity, unique identifiers were not collected and verbal informed consent was used. Data was collected on tablets using the Magpi mobile data platform (Datadyne LLC, Washington, DC). Partner organizations’ staff supervised interviewers and JHSPH performed real-time data review to ensure quality.

Data was analyzed using Stata 13 (College Station, TX) with the ‘svy’ command to account for clustering. Exploratory analysis was conducted to assess if differing non-response rates (0-21%) needed to be accounted for and it was found unnecessary. Summary statistics were not weighted because sampling survey area probabilities were similar and confidence in data used to estimate probabilities low. Sectoral severity scales were developed based on key indicators; cut points were determined by reviewing point estimates and categorizing to attain a distribution. Severity levels were assigned based on select sectoral indicators and the proportion of the population identified as at risk/affected by one or more indicators.

The primary purpose of the assessment was to inform partners’ humanitarian programming and the assessment was conducted by partner organizations’ staff. Permissions to conduct the survey were attained from local community leaders as needed in Syria by partner organizations and survey supervisors. The Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Institutional Review Board determined that JHSPH was not engaged in human research because JHSPH had no interaction with human subjects and was not obtaining identifiable data.

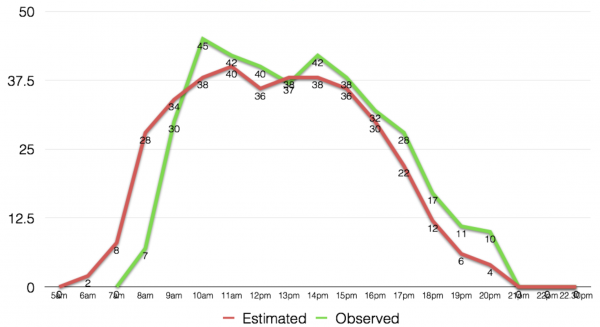

Results

A total of 2,681 households were approached to participate, of which 10.3% (n=276) declined, yielding a final sample of 2,405 households (response rate=89.7%). The average household head was 51 years old (range 16-103) and 17.7% (CI:15.7-19.8) of households were female-headed. Educational attainment was low with 60.0% (CI:55.9-63.9) of household heads not completing secondary schooling. Less than half (42.7%, CI:37.8-47.7) of households were displaced and 2.0% (CI:1.1-3.5) were returnees. Average household size was 5.1 (CI:4.9-5.3, range 1-22). A majority of households (65.4%, CI:61.9-68.7) had children ≤17 years and 29.3% (CI:26.3-32.4) had children <5 years of age; 37.1% (CI:34.3-40.0) had older adults. The population age distribution is presented in Figure 1. The most common vulnerable group was those with chronic health conditions, reported by 43.3% (CI:40.5-46.1) of households; 12.6% (CI:11.1-14.2) had disabled members and 7.7% (CI:6.5-9.2) had pregnant or lactating women.

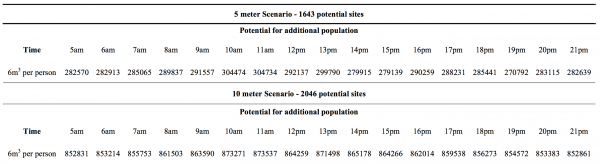

Figure 2. Age Distribution of the Population

Humanitarian Assistance and Unmet Needs. Humanitarian assistance was received by 45.1% of households in the preceding month; only 11.6% received multiple types of aid (Table 2, Figure 2). The most frequent assistance received were food items (42.7%) and hygiene kits (6.4%); ≤2.5% received aid in all other categories. Receipt of assistance differed significantly by region: more than half (52-57%) of households in Aleppo, Rif Damascus, the South, and the Central areas received assistance compared to 35% in Damascus and West Coast and 16.5% in al-Hasakeh (p<0.001). Unmet needs were nearly ubiquitous with 96.5% reporting one or more unmet need. The most frequently reported priority needs included more food (29.4%), rent support/improved shelter (15.4%), health services/medications (11.2%), improved security (10.8%) and better quality food (9.4%). Food (64.1%), non-food items (NFIs) (29.3%), health (26.8%), and shelter (24.4%) were the sectors with highest reported unmet needs. The proportion of households with unmet needs was similar across regions (p=0.208); however, priority needs varied by location (p<0.001). Of note were the large proportions in al-Hasakeh and Aleppo reporting food (70.0% vs 38.8% overall) and security (43.5% vs. 10.8% overall), respectively, as priority needs.

Figure 3. Severity of Humanitarian Assistance Needs by Sector and Region

Table 2. Receipt of Humanitarian Assistance and Unmet Needs

Shelter. Most households resided in an unshared houses or apartments (89.2%) with smaller proportions residing in unfinished buildings/construction sites/warehouses (4.8%), rented rooms (3.0%), or other accommodations (3.0%) (Table 3, Figure 2). More than half owned (56.3%) and many rented (31.8%) or were hosted (10.2%). Over half (62.1%) of households reported dwellings in good condition and 37.9% had a concern about their dwelling or needed shelter repairs; the most frequent problems included high humidity (27.0%), water leakage (10.4%), and poor ventilation (7.3%). Crowding was not a major concern; only 11.6% of households reported ≥5 people per sleeping room. Differences by geographic area were significant. The greatest need for repairs was in the West Coast (63.2%), crowding was most frequent in al-Hasakeh (30.5%), and a high proportion of Rif Damascus households (13.8%) lived in construction sites, unfinished buildings, or warehouses. Overall, shelter needs were greatest in the West Coast, al-Hasakeh, and Rif Damascus where more than half of households had at least one shelter indicator of concern.

Table 3. Shelter and Living Conditions

Food Security. Food security was assessed using the Food Consumption Score (FCS);12 7115.9% of households had an acceptable FCS (mean=55.2) (Table 4, Figure 2). Lack of food or insufficient means to buy food in the preceding month was reported by 38.1% and 56.7% reported no food stocks. Food assistance reliance was low with 72.4% reporting <25% of their diet from aid. Use of any and extreme coping strategies[1] in the preceding month were reported by 84.9% and 54.3% of households, respectively. Most frequent were reliance on less preferred/expensive foods (54.0%), spending savings (53.5%), credit/borrowing (40.1%) and reduced portion size (34.4%). A minority (12.8%) spent >75% of total expenditures on food. There were statistically significant differences in food security by region. Using FCS, food insecurity was highest in Rif Damascus, the Central and West Coast survey areas where 31.1-34.8%of households did not have an acceptable FCS. Both Rif Damascus and the West Coast had high prevalence of coping mechanism use with 67.5%-71.9% using extreme coping strategies. In al-Hasakeh, nearly half (47.7%) reported that >75% of total expenditures on food. Overall, food insecurity was most severe in Rif Damascus and the West Coast, moderate in Aleppo and the Central area, and lowest in Damascus and the South. In all areas, half to three-quarters (49.0-78.4%) of households were food insecure by one or more indicator making food insecurity the area of greatest unmet need.

Table 4. Household Food Security

Water & Sanitation. The most frequent drinking water source was an inside tap supplied by municipal water networks (79.6%) followed by paid tanker/truck water (11.8%); similarly, an inside tap was also the most frequent source of water for other purposes (90.4%) (Table 5, Figure 2). Water access was fair with 36.4% reporting not having access to water 24 hours a day; those without regular access reported having water for 12 hours daily. When running water was not available, sources included stored water (49.3%) or trucked water (34.3%); nearly all (97.9%) were able to store water and 72.5% had storage capacity >500L. Water access was perceived as a problem by 72.2% of households and nearly half (48.0%) reported no access for several days at a time in the three preceding months. With respect to sanitation, flush toilets (45.6%) and improved latrines (40.3%) were the most common; 18.1% of households did not have improved sanitation and 5.9% reported sharing toilet facilities.1716 Water and sanitation indicators differed significantly by region. The need for improved water access and water storage was greatest in Aleppo where the majority (88.8%) did not have continuous access to running water and 95.5% experienced several days without water in the 3 preceding months. Sanitation was the worst in the West Coast and Rif Damascus where 27.1% and 21.7% of households, respectively, lacked improved sanitation.

Table 5. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH)

[1][1] Including reducing portion size; reducing number of meals eaten per day; reduced adult consumption to allow children to eat; restricting consumption of female household members; going entire days without eating; selling household assets, productive assets, house or land; withdrawing children from school; involving children in income generation; engaging in high risk/socially degrading jobs; sending members to eat elsewhere; and child marriage.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the only recent quantitative multi-sectoral assessment that covers a significant proportion of Syria. The assessment was undertaken in areas that were predominantly government controlled which are less likely to have experienced direct effects of conflict, such as violence and infrastructure destruction, than inaccessible and non-government controlled areas. Basic services, such as health, education and utilities are likely to be more accessible and functioning in in areas included in the assessment as compared to elsewhere in Syria; furthermore, the participants were from predominantly urban areas which are likely to have better access to services than rural areas. Assessment findings should not be generalized to Syria more broadly because of contextual differences and it is likely that humanitarian needs in non-government controlled areas are significantly greater than in the locations included in this assessment.

The ability to compare results with other sources is limited because accessible areas and measurement methods vary widely. The 2016 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) and Syria Dynamic Monitoring Reports (DMR) have similarly wide geographic coverage and report on all sectors, but rely on secondary data or assorted other methodologies.1718,19 A number of sector-specific assessments and program evaluations are available, but there were no peer reviewed publications with primary data collected in 2015 or 2016.1920,21,22,23

Shelter needs were greatest in the West Coast, Rif Damascus, and al-Hasakeh, though concerns differed greatly by region. Residing in construction sites or warehouses was common in Rif Damascus whereas dwelling repairs and crowding were predominant concerns in the West Coast and al-Hasakeh, respectively. One potential reason for the high levels of crowding in al-Hasakeh is that displacement in al-Hasakeh was more recent than in other survey areas, where 69% of IDPs were displaced in/after 2015 compared to <10% in other survey areas. The June 2016 DMR indicated shelter needs were most severe in Rif Damascus, aligning with findings from this assessment; Homs also had higher shelter needs in the DMR. Comparison with other recent assessments suggest that our findings may underestimate shelter needs; in this assessment 38% were found to lack adequate shelter compared with 79% in the DMR and 59% reported by OCHA.19,2418

Food security was a major concern. Despite high levels of assistance, 64% of households had unmet food needs which is greater than our 2014 survey where 50% reported unmet food needs.2322 Food insecurity was greatest in Rif Damascus and the West Coast; Aleppo and the Central area were moderately food insecure and Damascus and the South were areas of lesser concern. Findings are relatively aligned with other sources; 85% of households reported using negative coping strategies compared to 79% in a June 2016 food security review.2524 Food consumption, which was acceptable in 76% of households, was slightly better than in a 2015 WFP report where only 65% had an acceptable FCS; this is difference is not likely to reflect a situational improvement and is probably results from differences in coverage areas.2122,23 High food prices and receipt of insufficient quantities of food, both previously identified concerns, are likely contributing factors to the observed high food expenditures and food insecurity.18,22,26,27

172125More than one-third (36%) of households did not have consistent access to running water and 48% reported no access to water for several day periods. Water access was worst in Aleppo and reported to be a problem by 72% of households overall. Sanitation was a lesser concern with 86% having improved sanitation and little sharing (6%); sanitation needs were greatest in the West Coast and Rif Damascus. Findings from this assessment, where Aleppo had the greatest WASH needs, are supported by previous assessments; however, Hama and Homs were ranked as having similarly high WASH needs in the HNO but moderate needs in this assessment.10,18 Of note, our assessment reports on access to water but could not assess water quality which is also a known concern, where 70% of Syrians are estimated not to have access to safe drinking water.18

Limitations. Triangulation and the stratified design may have reduced sampling bias, but given the limitations of available population data and ongoing displacement, it is likely the sample is unrepresentative. Many areas were inaccessible, thus findings are not nationally representative and probably present a better-than-actual characterization of the situation where the most severely affected areas with the greatest unmet needs were inaccessible; this was especially true in Aleppo, one of the most severely impacted areas, where the majority of the city was inaccessible.2827 The training-of-trainer method, particularly given the extended period between trainings, and use of paper questionnaires in some locations may have contributed to poor data quality. Because of length limitations; key sectors including health, NFIs, education and protection were not assessed in sufficient depth and had limited indicators that could be used to develop severity scales and thus are not presented.

Conclusions

Timely and accurate report of needs in emergencies is a persistent challenge. Situational reporting is often anecdotal or based on information provided by convenience samples, key informants, projections or a combination of these approaches. This assessment is the only large-scale multi-sectoral assessment conducted in Syria in the past two years that uses a random sample of households, thus findings are more scientifically rigorous than most other available sources.

The greatest levels of unmet humanitarian needs were observed in the West Coast, Rif Damascus, and al-Hasakeh. Of note, was the finding that Lattakia and Tartous had high unmet needs in both the shelter and food security sectors and moderate water and sanitation needs which contrasts with other recent reports indicating lower levels of need in those governorates.1817 Lattakia and Tartous are mostly government controlled, however, the proportion of households receiving assistance was among the lowest of all survey areas which may explain the higher than anticipated levels of unmet need. Al-Hasakeh differed from other areas included in the assessment in that displacement was more recent and coverage of humanitarian assistance was low, which is largely due to aid organizations having poor access (though indications are this may be improving). The high prevalence of coping mechanism use and other indicators suggest the population in al-Hasakeh is in need of additional support and that an expanded response could prevent future deterioration.

When considering these findings, it is important to note they are representative of accessible populations in predominantly urban areas which are likely to have better access to services and fewer needs than populations in rural locations or areas not controlled by the government. The humanitarian situation in inaccessible areas is likely to be considerably worse, thus findings presented here likely underestimate the true scope of humanitarian needs which will continue to exceed response capacity, both due to access limitations and funding shortfalls.1817 Extreme destruction and violence, widespread humanitarian law violations, and lack of progress towards peace portend a deteriorating situation. Sustained support from the international community and an expanded humanitarian response are desperately needed for Syrians to better endure the conflict.

Competing Interests

Shannon Doocy is on the Editorial Board at PLoS Currents. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Funding Disclosure

The study was funded by international donor contributions for humanitarian operations by a US-Based international non-governmental organization that wishes to remain unnamed. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding Author

Shannon Doocy: [email protected]

Data Availability

Minimal underlying data for this manuscript is deposited publicly in the Humanitarian Data Exchange and can be accessed at: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/humanitarian-needs-in-government-controlled-areas-of-syria

Methods: We implemented a pre-SIA survey in 135 randomly-selected households in Kobanê using a vaccination history questionnaire for all children <5 years. We conducted a VPD Risk Analysis using MSF ‘Preventive Vaccination in Humanitarian Emergencies’ guidance to prioritize antigens with the highest public health threat for mass vaccination activities. A Measles SIA was then implemented and followed by vaccine coverage survey in 282 randomly-selected households targeting children <5 years.

Results: The pre-SIA survey showed that 168/212 children (79.3%; 95%CI=72.7-84.6%) had received one vaccine or more in their lifetime. Forty-three children (20.3%; 95%CI: 15.1-26.6%) had received all vaccines due by their age; only one was <12 months old and this child had received all vaccinations outside of Syria. The VPD Risk Analysis prioritised measles, Haemophilus Influenza type B (Hib) and Pneumococcus vaccinations. In the measles SIA, 3410 children aged 6-59 months were vaccinated. The use of multiple small vaccination sites to reduce risks associated with crowds in this active conflict setting was noted as a lesson learnt. The post-SIA survey estimated 82% (95%CI: 76.9-85.9%; n=229/280) measles vaccination coverage in children 6-59 months.

Discussion: As a result of the conflict in Syria, the progressive collapse of the health care system in Kobanê has resulted in low vaccine coverage rates, particularly in younger age groups. The repeated displacements of the population, attacks on health institutions and exodus of healthcare workers, challenge the resumption of routine immunization in this conflict setting and limit the use of SIAs to ensure sustainable immunity to VPDs. We have shown that the risk for several VPDs in Kobanê remains high.

Conclusion: We call on all health actors and the international community to work towards re-establishment of routine immunisation activities as a priority to ensure that children who have had no access to vaccination in the last five years are adequately protected for VPDs as soon as possible.

]]>Introduction

The on-going, protracted conflict in Syria has led to a large scale breakdown of health services with a decrease in life expectancy and an increase in childhood mortality since the war began that has obliterated the public health gains being made in the past 1,2,3. Despite moderately high pre-conflict vaccine preventable disease (VPD) vaccination coverage rates in Syria 4 , recent reports of outbreaks of acute flaccid paralysis and measles have become increasingly common 5,6,7. While much has been documented about the health status of Syrians who are hosted as refugees in other countries, insufficient information is available about the effects of the conflict on the health of the population inside Syria 8 .

Kobanê (formerly Ayn al-Arab) is a town in Aleppo governorate in northern Syria. It participated in the full national Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) prior to 2011. The implementation of EPI deteriorated as the conflict progressed and the programme was discontinued nationwide by mid-2014 9. Since then only some supplementary immunization activity (SIA) with oral polio vaccine was carried out by local authorities and supported by UNICEF.

The majority of the population of Kobanê fled the town at the end of 2014 following the takeover by the Islamic State (ISIS) with the majority of the 60,000 inhabitants taking refuge in neighbouring Turkey. In Turkey, some children re-started EPI as refugees. By the first half of 2015, people started returning to Kobanê as active fighting had subsided and as access improved, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) restarted healthcare activities in the region. A population census that was conducted by MSF and a local community-based organisation in May 2015 indicated that 24,000 people were living in Kobanê city at that time, across 4400 households.

In May 2015, continued population movement, limited access to health services and poor water and sanitation created ideal conditions for outbreaks of VPD amongst the returning population. Given the complete lack of routine vaccination, absence of recent coverage data and the risk of VPD transmission in this setting, MSF conducted a vaccine coverage survey in order to make an informed decision about prioritisation of public health interventions, particularly vaccination.

Based on the results of the survey and the VPD risk assessment that followed, measles SIA (i.e. a mass vaccination campaign) was carried out in Kobanê city and the surrounding county by the Kobanê Health Administration (KHA) with the support of MSF. This was followed by a post vaccination coverage survey to monitor the success of the SIA.

We describe the methodological processes and findings of the initial vaccination coverage survey, VPD risk analysis, mass measles vaccination program and subsequent post-campaign vaccination coverage survey in this conflict affected area. The information highlights the impact of the conflict on the vaccination status of Syrian children and the grave public health risks associated with this.

Methodology

Pre-SIA Vaccine Coverage Survey

Target population and sample size