Methods: In accordance with the PRISMA statement, “PubMed”, “ScienceDirect”, “Google Scholar”, and “Scopus” were searched up to end of 2015. All English Articles that were published in peer-reviewed journals and had discussed site selection criteria for hospitals were included. Out of 41 articles, 15 met the inclusion criteria in which 39 general criteria for HSS were applied. These criteria were categorized in six main groups including cost, demand, environmental, administrative, disaster risk, and “other” concerns through a focus group discussion.

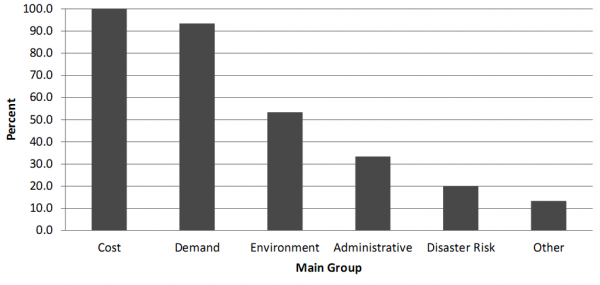

Results: Accordingly, the application percentage of cost, demand, environmental, administrative, disaster risk, and “other” concerns in the articles was 100, 93.3, 53.3, 33.3, 20.0, and 13.3 respectively. The least devoted attention was to disaster risk issues.

Discussion: Few researchers applied risk related criteria for HSS. Further consideration of “risk of hazards” and “burden of diseases” in comprehensive studies, is recommended for HSS to guide the decision makers for building more resilient hospitals. Keywords Hospital, Site selection, Systematic review, Disaster risk

]]>Introduction

Hospitals are one of the main elements of social services, and a cornerstone of response to disasters in an acute phase, especially in countless mass casualty incidents. Social service delivery has its roots in the time when humans began living together as a community to meet their needs. Accordingly, health-related services were developed particularly in more centralized populations, when diseases and injuries became one of the most challenges besides food and water1.

The percentage of people living in cities is rapidly increasing due to having an easy access to social services. To provide a chance for having equitable access to hospitals a convenient location of establishing the service centers is of great importance1. In the decision-making process to establish a new hospital or renovate an old one proper location plays an important role specifically with regard to guaranteeing the profit return on investment. In other words, determining the location of a hospital is an important factor that can affect the cost and benefits2. In 2006, Younis et al showed that the geographic location influences the profitability of a hospital i.e. financial performance3. Considering the projections related to the increase in urban population to greater than 5 billion by 2025 and its effects on increasing the vulnerability in addition to climate-change related risks, assigning a proper location for medical centers becomes a crucial factor for planners4,5,6, given its long time impacts7. For instance, in a study by Bell (2007) it was indicated that the location of a hospital would have a direct effect on survival in situations such as nuclear attacks8. Also Ochi (2014) stated that inappropriate location may cause damages to a hospital due to external hazards such as earthquakes9.

On the other hand, Sendai framework emphasizes structural disaster risk prevention and reduction measures as well as the promotion of resilience of new and existing critical infrastructures such as hospitals10.

In this regard, there are two main theories used to optimize hospital location. The first is based on the Weberian model, which focuses on a single objective namely the minimum cost or maximum profit. (WU 2007) The second theory has its roots in “behavioral approach” which simultaneously considers several factors to determine the most appropriate location. For instance, Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) method, is based on “behavioral approach”11.

The present study through a systematic review aims to retrieve a list of disaster risk related criteria applied in hospital site selection (HSS).

Methods

Study design

This study is a descriptive systematic review investigating risk criteria in HSS. The 27-item Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis statement (PRISMA) 2009 checklist is used as a reference12. The study protocol was approved by the Higher Education Council of School of Public Health at Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Search methods for identification of studies

In the present study, “hospital “refers to the legal institution that provides 24-h medical services, including accepting, visiting, admission, and treatment of injured and/or sick individuals13,14. “Site selection” refers to an operational problem solving research in which the researchers will find out the best location that meets the assigned preferences15. “Risk” refers to both the probability of an event (hazard) and its impacts on the exposed community (vulnerability)16.

Initially, four electronic databases (MEDLINE through PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct and Google Scholar) were searched up to December 31; 2015.The search strategy was based on the PubMed database model. The key terms were adopted from Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) when possible; otherwise appropriate key words were selected according to the expert idea. The expert team is including the authors’ team and 3 more volunteer PhD students at Health in Emergencies and Disasters from Tehran University of Medical Sciences with previous field experiences in disaster medicine. Titles and abstracts were searched with the following syntax:

Study eligibility

The inclusion criteria were articles that were published in peer-reviewed journals and had site selection criteria for a hospital. Gray literature including conference proceeding papers and thesis were included as well. All non-English articles were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

The key terms were searched in the databases separately and all articles were imported to a bibliographic management program (EndNote X3). Duplications were then omitted. The titles and abstracts were evaluated by two authors (MJM and BR) independently; in the cases that the exclusion criteria could not be applied, the full article was reviewed. If there was disagreement about the eligibility of a particular article between MJM and BR, the third author (AA) was asked to adjudicate. The electronic search was conducted from November 2015 to December 2015.

In the next step, the data were extracted out of the full-text of the included articles. This data included the first author’s name, the year of publication, and the first author’s country, the geographical scope, site selection criteria and the method of study. The references of selected articles was hand searched. Finally, the extracted site selection criteria were categorized through a focus group discussion by the expert team which has been described above already. The final results were sent to the expert team for confirmation through e-mails.

Quality assessment

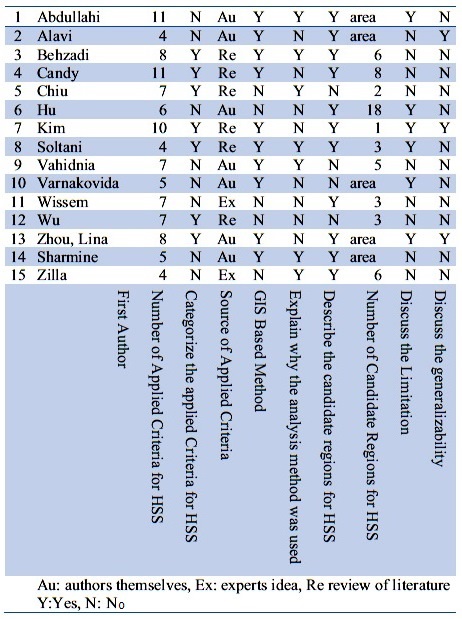

A 9-question checklist was produced to assess the quality of the retrieved publications by authors (Table 3). The Quality-related questions investigated the following components: number of applied criteria for HSS, categorization of the applied criteria (Yes or No), source of applied criteria (i.e. the authors themselves, experts idea or review of literature) , GIS based method (Yes or No), explanation of why the analysis method was used (Yes or No), description of the candidate regions for HSS (Yes or No), number of candidate regions for HSS (i.e. the number of regions or a countless sites), discussion about the limitation (Yes or No), and discussion about the generalizability of the study (Yes or No).

The checklist was filled out by two assessors independently (MJM and BR) and “AA” adjudicated when there was disagreement.

Results

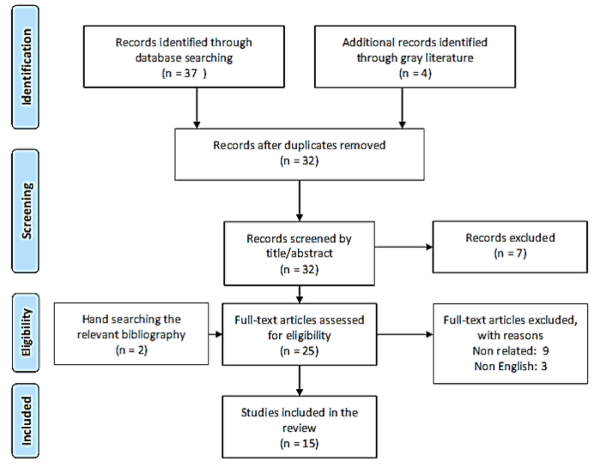

In the first step 41 studies were retrieved through the bibliographic search. After removing seven irrelevant and nine duplicates, 25 were remained. Sifting process left 15 eligible studies that were published up to the end of December 2015, 2 of them were identified from hand searching of references of included articles. Figure 1 illustrates the related PRISMA flow diagram. The result of quality assessment is summarized in Supporting Information file, S1 Table.

Fig. 1: PRISMA Flow diagram for systematic review of hospital site selection criteria

Table 1 summarizes the main results of the present study. The first article was published in 199517. The maximum number of articles were published in 2013, i.e., 6 articles. The total number of authors of the included articles was 38 (2.7 authors per article, in average). The first/corresponding authors were affiliated with different universities; among these, only K.N.Toosi University of Technology (in Iran) was associated with two publications2,18.

Table 1: Main results of the systematic review about disaster risk criteria for hospital site selection

HSS studies performed in China were 2, Iran (5), USA (2), Taiwan (2), Tunisia, South Africa, Israel and Bangladesh (1). Regarding the geographical scope, three studies were performed at the provincial or state level, two at the country level, five at the city level, and five at a district of a city.

With regard to the methodology, 10 articles used Geographical Information System (GIS), 5 studies applied AHP, and one used fuzzy AHP for site selection19. One study combined the AHP with the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method18 while another one combined AHP with the Rank Order Method (ROM)20. Other models that were used included mathematical modeling, Belief-Desire-Intention (BDI)2, Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution TOPSIS1, goal programming11, fuzzy Analytical Network Process (ANP)7, and travel-time methodology21.

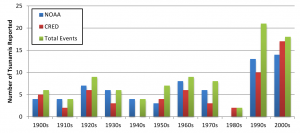

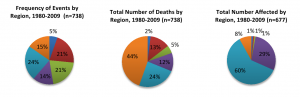

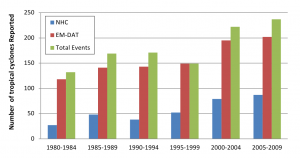

Through a focus group discussion, with the above described expert team, all 39 HSS criteria were classified into six main groups namely cost, demand, environmental, administrative, disaster risk, and other concerns. The application percentage of each of these groups was 100, 93.3, 53.3, 33.3, 20.0, and 13.3 respectively (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Usage of main groups of Hospital Site Selection Criteria in included articles.

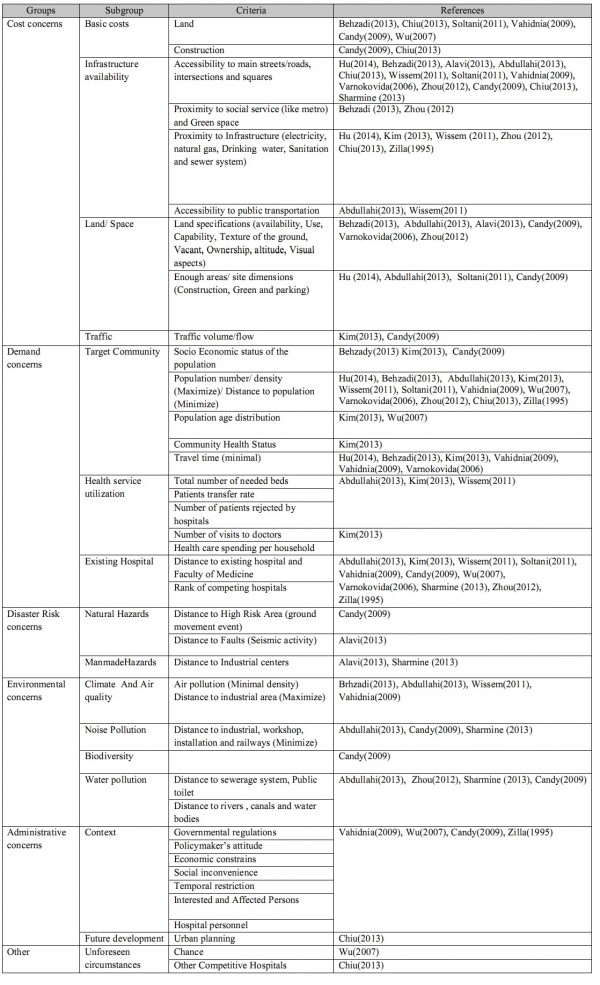

The six mentioned groups were subsequently divided into 16 subgroups (Table 2).

Table 2: List of classified criteria for hospital site selection in included articles

Discussion

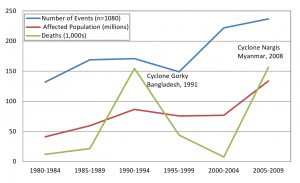

This systematic review was conducted to find out the disaster risk related criteria for HSS. According to the results, despite the increasing trend of worldwide disasters, risk related criteria are not taken into consideration to the extent that they should.

It is not mandatory and also not realistic to apply all these factors for HSS. Depending on the strategy for building medical centers, the planners may consider only some of these. For example, Kim et al (2013) conducted HSS in the construction of a hospital for the aging population and considered factors that looked at the real health requirements of the target group; thus, some criteria such as environmental issues (air and sound pollution and sewerage system) were not considered22. Soltani et al (2011) used several criteria such as urban planning, traffic volume, and travel time for site selection of a hospital in district five of Shiraz, Iran; however they did not consider environmental and land specification issues in their study7. As the main goal of Wu et al (2007) was ensuring competitive advantage for HSS, they considered administrative criteria such as regulations, policymaker’s attitude, and even demand for the hospital personnel. They did not consider environmental concerns and accessibility to infrastructures such as main roads, as well23.

Alavi et al. (2013) considered two groups of factors that affect accessibility (roads and social services) and also distance from potential hazards (faults and industrial centers) for one region of the capital city of Tehran, Iran. However they did not use future planning development, real demand for hospital in the region, existing health services, and other land specifications1. Also Jing-Er Chiu and Hang-Hao Tsai (2013) used MCDM to determine the optimal location for expansion of a regional teaching hospital in Yunlin County, Taiwan. They used highly detailed criteria including the demand for medical service, cost, transportation, sector support, and future development. The main theme considered in their study was increasing the competitive advantage for the hospital24.

In 2014, Xiao-Hua Hu et al developed a model to identify the proper location for medical and health services in a large group of islands in Hainan Province in China. This model was based on minimizing the travel distance for clients of these services. In this study, the real demand and environmental issues were not considered25.

To achieve sustainable development, a community should consider important issues in building and utilizing a new hospital. In HSS procedures, environmental considerations are important issues26,27,28. While important, the majority of publications devoted more attention to cost and demand rather than environmental issues such as air and noise pollution as these have sever negative effects on hospital functions. In addition, following the completion of the hospital, these types of pollution would be aggravated.

Regarding the cost concerns, most of the studies devoted attention to accessibility by main roads and arteries. Other cost subgroups were proximity to infrastructures, and land specifications (availability, use, texture of the ground, being vacant, and ownership). However, none of the articles discussed the beneficial aspect of the proximity of the hospital location to airports or seaports.

Concerning the demand category, health service utilization of the community was assessed according to the total number of required beds, the patient transfer rate, and the number of patients rejected by hospitals11,18,22. In this category, epidemiological indices such as “burden of disease” and forecasting demand for health care based on demographic factors, economic growth in the area, and even new technologies in health system could be considered. For example, oil and energy activities are a great source of economic development but require a certain type of health care infrastructure when it comes to emergency medical services including trauma and cardiac patients.

As construction of a hospital is a kind of investment, the investors wait for future profit. Hence, threats to this investment should be taken into account. For more than 25 years, WHO has promoted and supported the efforts to the purpose of safe hospitals to improve the function of hospitals in emergencies and disasters. Besides, in Sendai Framework (2015-2030)10 the application of the principles of universal design and standardization of building materials in critical facilities such as hospitals is considered with the aim of disaster risk prevention and reduction. Unfortunately, few articles discussed hazards such as faults and industrial areas 1,11,27. Other potential hazards, such as floods and man-made disasters, should be considered for at-risk areas. Considering the “risk”, rather than merely hazards, is highly recommended in future permanent and field hospital site selection studies.

The two unclassified criteria, namely unforeseen circumstances and other competitive hospitals were considered in the “Other” category. It is recommended that the safety and security of the candidate locations, rural versus urban areas, local investors, accessibility of communication systems, and availability of competent and qualified staff be considered in this category in further studies.

Conclusions

Despite the critical role of hospitals in health service delivery in disasters and emergencies and the effect of hospital location on the quality of these services, few articles have considered hazards as the criteria for hospital site selection (HSS). Cost and demand are two groups of criteria that have been addressed more frequently in HSS studies. The decision makers should prospectively match the main objectives of hospital building with the HSS criteria according to the strategy of site selection and the availability of data and resources. Undoubtedly, being safe and remaining functional in emergencies and disasters should be one of the main objectives in HSS in line with Sendai Framework. More comprehensive criteria like “risk of hazards” and “burden of diseases” are suggested to be considered in future studies.

Limitations

Non-English articles were not included in this study.

Supporting Information

S1 Table: Quality assessment results for included publication in HSS systematic review

Corresponding Author

Ali Ardalan, MD, PhD

E-mail: [email protected]

Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Data Availability

All relevant data are in the article.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

This short report presents a response to the article written by Cibulsky et al. (2016) 1 ‘Mass casualty decontamination in a chemical or radiological/ nuclear incident with external contamination: guiding principles and research needs’. The paper by Cibulsky et al. presents a useful and timely overview of the evidence surrounding the technical and operational aspects of mass casualty decontamination. It identifies three priority targets for future research: operational analysis to determine the best ways to integrate casualty decontamination into the incident response and coordinate it with medical evaluation and treatment; comparative study of the efficacy of various decontamination methods and their potential adverse effects; and behavioural, communication and privacy issues, including what casualties and community members need during an incident that requires mass decontamination, and how their needs can be met in ways that best support compliance with and effectiveness of casualty decontamination.

We agree that each of these areas is a priority for future research. However, while further investigation into behavioural, communication and privacy issues during mass decontamination is warranted, there is now a substantial body of research in this area which is not considered in detail in the succinct summary provided by Cibulsky et al. (2016) 1. In this short report, we summarise the available evidence around likely public behaviour during mass decontamination, effective communication strategies, and potential issues resulting from a lack of privacy. Our intention is to help further focus the research needs in this area and highlight topics on which more research is needed.

Behavioural (likely public behaviour)

Traditionally, planning and policy for mass decontamination has focused on the technical aspects of mass decontamination, such as developing and testing decontamination equipment, with little consideration of likely public behaviour. Where likely public behaviour has been considered in planning for incidents involving mass decontamination, there has been a reliance on common myths about crowd behaviour, such as inherent public disorder and mass panic 2. However, over 50 years of research has shown that panic occurs very rarely during mass emergencies and disasters, and that people are much more likely to behave in a helpful and cooperative way 3,4,5,6,7. This reliance on assumptions about panic has resulted in little attempt to develop strategies for communicating with members of the public during decontamination; if people are going to behave in an irrational way then there won’t be any point in trying to communicate with them. Indeed, research suggests that assumptions about panic may lead to information being withheld from members of the public, which may actually create the very disorder 8,9 and non-compliance 10 which authorities are hoping to prevent.

Evidence from small-scale incidents involving decontamination shows that those people who are affected may refuse to comply with decontamination procedures if they are not provided with sufficient information about why decontamination is necessary, and what the process involves 2. Findings from large-scale field exercises and field trials involving mass decontamination suggest that, if sufficient information is provided and the people involved believe that responders are being open with them, members of the public are likely to be willing to comply with decontamination 11,12, and also willing to help others to undergo decontamination 12,13.

Overall, these research studies show that public behaviour is likely to be contingent on the way in which emergency responders manage the incident. Emergency responders who communicate effectively with members of the public and show respect for their needs change the relationships and that, consequently, results in more positive outcomes from the incident, in terms of reduced public anxiety and increased public compliance and cooperation. Thus, if managed well, members of the public can actually be an asset to emergency responders in their attempts to successfully manage the incident.

Communication and privacy

Effective communication is essential during mass decontamination – failure to communicate effectively can result in reduced public compliance and cooperation, increased confusion, and even attempts to challenge responders’ authority. Several research studies have examined how different perceptions of responder communication can affect public compliance and cooperation, as well as levels of public anxiety, during mass decontamination 11,14,15.

A recent mass decontamination field experiment specifically tested three different responder communication strategies, in order to try to identify what makes some communication strategies more effective than others 12. Results from this study revealed that, for a communication strategy to be effective during mass decontamination, it should include open and honest information about the nature of the incident, health-focused explanations about the importance of decontamination, and sufficient practical information to enable those people who are affected to successfully undergo decontamination. Crucially, the inclusion of an effective communication strategy not only resulted in more positive psychological outcomes for those affected, it also resulted in improved speed and efficiency of decontamination on objective measures 12. Therefore, this could save lives during a real incident.

As well as the provision of effective responder communication, another key issue during mass decontamination will be whether members of the public feel they have sufficient privacy 16,17,18. It is crucial that emergency responders show that they are doing what they can to respect public needs for privacy and modesty; failure to do so can result in reduced public compliance and cooperation 2,12,13,14,19.

Several research studies have examined the mechanisms underlying the relationships between effective responder communication, sufficient privacy, and positive outcomes during mass decontamination 12,14,20. Findings show that effective communication from emergency responders and the provision of sufficient privacy are crucial because they enhance public perceptions that responders are behaving in a legitimate way. Enhanced perceptions of responder legitimacy facilitate increased identification between members of the public and emergency responders, as well as amongst members of the public, and it is this identification which leads members of the public to actively engage with the decontamination process.

The findings from these research studies have been used to generate recommendations for emergency responders when managing incidents involving mass decontamination 15, and so far have been included in US decontamination guidance documents for emergency responders 21,22,23.

Conclusion

This research programme can be used to inform best practice for managing casualties during mass decontamination. However, as noted in Cibulsky et al. (2016)1, there is a need for further research in this area to optimise casualty management strategies for mass decontamination. Ongoing work related to the development of optimal management strategies for mass decontamination is being carried out as part of the NIHR Emergency Preparedness and Response Health Protection Research Unit (EPR HPRU) (https://epr.hpru.nihr.ac.uk/). This research includes a qualitative study of factors which affect perceived public acceptability of different decontamination methods, part of which involves testing the effect of different responder management strategies on perceived public acceptability of mass decontamination. The research also examines cultural factors which may affect public willingness to comply with different decontamination methods. Further research could include analysis of data from real incidents involving decontamination, as well as new field studies and exercises testing different responder management strategies. In particular, future research should consider practical aspects of communication, such as how best to deliver information to members of the public during the decontamination process, and also how best to protect casualties’ privacy and so promote compliance with the decontamination process.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Correspondence

Holly Carter: [email protected]

Methods: The current review presents a conceptual framework for studying psychological aspects of crisis and risk communication using the social media through social computing.

Results: Advanced analytical tools can be integrated in the processes and objectives of crisis communication. The availability of the computational techniques can improve communication with the public by a process of Hyper-Targeted Crisis Communication.

Discussion: The review suggests that using advanced computational tools for target-audience profiling and linguistic matching in social media, can facilitate more sensitive and personalized emergency communication.

]]>Background

The extensive use of social media in modern lives redefines social interaction and communication. Many of us are heavy consumers of the different channels of the social media, whether it is social networks, microblogs, photo sharing, forums, blogs or other types of the media. Nowadays, we are passive absorbers of information and active distributers of it. Many people spend a considerable portion of their time maintaining their virtual social networks, expressing themselves in different settings, staying tuned with the latest news and finding relevant information. During and following crisis or emergency situations, people turn to social media for various reasons, to make sense of the world through words, or as described by Lahad1 for the natural need of the storytelling animal’. We express ourselves and share our inner world through combination of words that others instantly absorb, process and act upon.

Disaster situations increase the need for information. The need, roots from high levels of uncertainty, true threats to life or health, and often manifest themselves in an urgent necessity for immediate information2. Effective crisis communications can therefore serve to mitigate anxiogenesis and direct rapid and focused rescue, recovery, and rehabilitative operations3. In the past, in such situations, the mass media disseminated messages and information to the public. Social media has revolutionized how individuals interact and how organizations and decision makers communicate with the public during routine and emergency times through the possibility of mass interactive communication. It has been suggested by practitioners that successful message phrasing, delivered to specific groups with specific characteristics, plays a crucial role in the communication process 4. While tuning to the public is a challenging task, the application of state of the art computational methods on the huge amount of user-generated textual content in social media, can enhance public understanding through insight extraction.

The current review seeks to clarify the following topics:

Finally, we will discuss where and how the introduction of new media and the advancement of social computational approaches calls for an update of theories and models of crisis communication.

Literature Review

Social Media and Crisis

The rise and proliferation of Web 2.0 applications revolutionized the way people interact and collaborate with each other. At the core of the Web 2.0 framework, are the social media, “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content (UGC)”6. Social media nowadays includes collaborative projects, blogs and microblogs, content communities, social networking sites, virtual game worlds and virtual social worlds. Through these applications, users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content. This user-generated content in a changing and dynamic virtual community creates a massive and unstructured data6.

In modern society, the significance of the social media in everyday life has increased dramatically, turning the world into a “global village”7. Since the late-20th century, new methods of mass media including the internet, cellular technologies and personal portable devices, have been considered as fulfilling a significant role in agenda setting and framing8, creating social capital9, and affecting politics, society and culture10. According to a recent report that summarizes social, digital & mobile statistics among global users11, 42% of world’s population are active internet users, and above one-quarter have active social media accounts. With regard to social networking platforms, the report shows that there are 1.36 billion Facebook users, 629 Million Qzone users (Chinese social network), 343 million Google+ users, 300 million Linkedin users and 271 million Twitter users. Twitter, a microblogging communication platform, for instance, reaches an estimated total of over 50 million tweets per day12, and during crisis twitter activity increases exponentially13.

Social media has become an essential mean of communication during disasters and it has been suggested that best practices need to be established to assist organizations, government and decision makers in optimizing risk and crisis communication in this era 14. Houston et al.15 developed a framework for the practice and study of disaster social media. They note that disaster social media users in the framework include communities, government, individuals, organisations, and media outlets. Those players seek to gain insights from the massive user-generated content published in the communication channels, provided by the social media platforms. This published timely information is quickly spread across multiple social networks, and may affect, shape or direct public behavior without official involvement or even in contradiction to formal instructions 16. Although many challenges exist during social media message processing and analysis, (e.g. management of information overload, credibility issues, and prioritizing different classes of messages), state of the art computational methods exist to carry out complex information processing operations. 17

Crisis Communication

Crisis communication can be defined broadly as the collection, processing, and dissemination of information required addressing a crisis situation. Crisis communication is a research and practice field in various setting and crises; including national18, organizational crises19,20 , natural21 , man-made22 and technological disasters23. Effective communication with the public remains a crucial role in public safety through crisis preparation and response24. The media are critical for facilitating pre-disaster preparedness, disseminating warning messages of pending disasters, providing information to citizens about the disaster, and facilitating recovery efforts25. Moreover, according to Firestone & Everly3 , crisis communications can play an important role in mitigating, or exacerbating, the psychological and behavioral reactions to critical incidents and disasters. One important adjacent field of crisis communication is Risk Communication, defined as any purposeful exchange of information about health or environmental risks between interested parties (e.g. governments, agencies, media, citizens and more)26. Reynolds and Seeger27 prposed a merged and comprehensive approach called “crisis and emergency risk communication”.

Social Media as a crisis communication platform

Social media has been radically changing the communication landscape over the past several years and as a result, crisis communication is undergoing substantial change28. It becomes clear that social media serves as ultimate space for crisis communication processes. Implementation of traditional crisis communication activities, was identified as one of the functions of disaster social media15. A recent survey29 of about 288 government officials in the US revealed that 71% of them were using social media during crisis, with Facebook as the popular social medium. Officials used social media during various types of crises, including public health30, natural disasters, transportational, political, social and criminal crises. Researchers found that the degree of social media use, rather than the number of tools used, was positively correlated with local city officials’ evaluations of their ability to control a crisis situation and the strength of their responses29.

Another research team31 systematically investigated crisis messages collected from Twitter. Relevant tweets for 26 different crisis situations that took place in 2012 were sampled from the available public twitter stream, and for each situation types of information and sources of that information were examined. During crisis situation, eyewitnesses, government, NGOs, business, media & news organizations and outsiders participate and publish different information types in social media 31. Types of information include data about affected individuals (e.g. people trapped, casualties, people missing, found or seen), infrastructure & utilities (e.g. damages, reports about environment, and availability of services), donations & volunteer (e.g. donations of money, goods of services; requesting help; shelter needed, food shortage/distribution; volunteer information); caution & advice (e.g. warnings, preparation; caution & advice; tips; safety), sympathy & emotional support (e.g. concerns and condolences; gratitude, prayers; support; emotion-related info) and other useful information (e.g. flood level; weather, wind, visibility; information verification). Based on the available data of that study (https://crisislex.org/tweet-collections.html), it seems that the Government, being the official source of information during crisis, was responsible for less than 5% of all published information. Of the applicable information types, the majority (32%) of the communication efforts by the government were about useful information (32%) and caution and advice (27%). Only 6% of the published tweets concerned about sympathy and support.

Effective Crisis Communication.

Seeger32 demonstrated ten best practices of crisis communication, drawn from a literature review and verified by expert crisis communication panel that reached high consensus. Seeger32 divides the recommendations into three broad categories: strategic planning, proactive strategies and strategic response. These are used as principles or processes that underlie an effective crisis communication plan and an effective crisis response.

Covello, McCallum, & Pavlova33 note that detailed, in-depth knowledge and understanding of both the characteristics of target audience and the community in which the target audience resides, are needed for effective message development. Target audience characteristics include knowledge, attitudes, perception, behavior, beliefs, values, needs and concerns, while community characteristics include information about social networks, opinion leaders and community dynamics. Covello34 suggested several risk communication templates to utilize in the process of risk communication: 1) CCO (Compassion, Conviction, Optimism) template, which is particularly useful when responding to a question indicating a high level of emotion or outrage4. 2) Primacy/Recency template35 emphasizes the first and last messages in the communication due to the restriction of recall of information. 3) 27/9/3 template states that the combination of the three key messages should equal a total of 27 words, 9 seconds spoken aloud, and 3 key messages34. 4) AGL-4 (Average Grade Level minus 4)4 template recommends phrasing the message at four reading grade levels below that of the stakeholder – taking into account the national reading grade level. 5) 1N=3P (Negative equals 3 positives) template counterattacks the weight of negative messages by introducing three positive messages for every negative message. 5) TBC (Trust, Benefits, Control) template suggests to phrase three messages that are phrased with specific order and content (trust first, benefits second and control last). These templates, however, were not empirically tested and thus limit our certainty regarding effective messaging.

The media plays a crucial role in shaping public response to terrorism and other disasters25. Effective crisis communication suggests the need of an unhindered but purposeful exchange of information within and between authorities, organizations, media, involved individuals, and groups before, during, and after a crisis36. Covello et al.33 also argue that risk communication is no longer a neglected topic within government. With the changing media environment and the developing online atmosphere, traditional media are shifting to practices that are more adapt to a social media environment37. Furthermore, to improve services and communication with the population, government officials seek to leverage these new media channels. Nevertheless, Graham, Avery & Park29 emphasize that government’s engagement through social media should be more active and reflect a clear response priority in crisis communication plans. Ambiguous or unreliable communications can cause damage and serve to exacerbate publics’ mental health reactions and a delay in operational response and recovery38To conclude, it is important to incorporate the use of citizen generated content into any crisis plan and learn to respond to the media and public even quicker than before39

Models and theories of Crisis Communication. Over the years several models of crisis communication were developed40, such as the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT41). SCCT “predicts the reputational threat presented by a crisis prescribes crisis response strategies designed to protect reputational assets”41, especially in organizational context.

Chaos Theory42 was described as a general framework for understanding crisis communication43. CT argues that chaos or disorder may be the necessary precursor of a higher level of order. CT functions best at the broad level of a paradigm for understanding the behavior of complex systems. Seeger43 adds that in the context of CT, small variance in communication processes, message phrasing, distribution, timing or other factors may produce extensive fluctuations in systems, leading to bifurcation.

Reynolds & Seeger27 presented the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) five-stage integrative model. The model blends crisis and risk communication together into a processes model (see27), assuming that crises will develop and progress in a predictable and systematic ways. According to the working model of CERC, communication processes occur during five stages: 1) Pre-crisis, 2) Initial Event, 3) Maintenance, 4) Resolution and 5) Evaluation. In each stage, communication can have different aims, strategies and target audiences.

With the advancing new media, the social media aspect was integrated in these models. For instance, the Social Media Audience Sharing Model (SMA)²24 aims to increase the reach for messages disseminated via a given social media platform in the context of an emergency. Social mediated crisis communication model (SCCM)44 is another model that serves as a framework for crisis communication management in the changing media landscape and explains how the source and form of crisis information affect organizations response options and provides recommended social-mediated crisis response strategies. The Networked crisis communication model45 examines the influence of communication strategy and media type on damage to reputation, as well as secondary crisis communication and secondary crisis reactions. Although these models recognize new players in the crisis communication processes (e.g. influential social media creators, follower, and the growing empirical evidence that emphasizes the psychological functions of social media during emergency management – during most of the time, less or no consideration is given to psychosocial aspects during crisis communication. The need to focus on other participants (such as the public) rather than the organization or the responding authority, is echoed in Liu & Fraustino46 who suggests that scholars should move beyond predominantly focusing on image management, emphasized by dominant crisis communication theories

Accommodated Communication

Considerable research, using text derived from social interactions, such as natural conversations and social media conversations, suggests that individuals tend to converge in various dimensions such as posture, pause length, utterance length, self-disclosure, head nodding, backchannels and linguistic style47. Niederhoffer & Pennebaker48 studied psychometric properties of language in dyadic interactions and assessed the degree to which people coordinate their word use in natural conversations, derived from internet chat and laboratory conversations. Based on a text-analysis software, they found that individuals in dyadic interactions exhibited linguistic style matching (LSM) on both the conversation level as well as on a turn-by-turn level. LSM found in research to be a predictor of social dynamics in small online and face-to-face groups49. LSM, also found to be a robust marker for romantic relationship stability, stressing the importance of similarity in the way people converse with each other in the context of interpersonal processes50. Lord, Sheng, Imel, Baer & Atkins51 saw that’s language style synchrony between client and therapist was predictive of empathy ratings during evidence-based behavioral treatments like motivational interviewing (MI). Therefore, it is apparent that synchronized verbal behavior holds an important role in various interpersonal interactions.

LSM, in fact is a derivative of Communication (or speech) Accommodation Theory (CAT), an intergroup theory of interpersonal communication, provides a framework for understanding how and why people adapt their communication toward and away from others and the social consequences of doing so. The theory holds that people tend to preform accommodative and non-accommodative moves, to reduce or increase significant social distances between the speakers, depending on the different circumstances. Convergence and divergence, called in the CAT approximation strategies, include the adaptation (or the alteration) of communicative behaviors in terms of wide range of linguistic-prosodic-nonverbal features. The theory also proposes different patterns of accommodation (upward vs. downward, and symmetrical or asymmetrical), based on the reciprocity of the speakers52. During the last years, examination of CAT progressed to the domain of electronic communication, such as e-mail, text messages, voice mail and recently also was adapted to electronic communications and the social media sphere. Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al.47 examined and verified the hypothesis of accommodated communication in the context of twitter conversations. The researchers developed a probabilistic framework that enabled to model accommodation and measure its effects. They focused on linguistic style feature, derived from the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count53.

To the best of our knowledge, CAT was never integrated in any crisis communication models published in the academic literature. The closest domain LSM, was mainly researched in the context of crisis negotiations of suicidal and surrender outcomes, and hostage taking negotiation outcomes54,55,56. In these studies, the researchers analyzed the correlations between the linguistic behavior of each communicator across 18 linguistic dimensions, like word count, prepositions, negations, emotionally toned words and others. LSM was assessed by the strength of the correlation and averaged across all conversations taken into account. The studies showed that negotiators (police officers and hostage takers) tended to show greater levels of linguistic style matching in successful negotiations compared to unsuccessful negotiations57, and an overall consistency in the linguistic behavior of subjects and police negotiators in surrender and suicide incidents54.

Interestingly, linguistic matching or accommodated communication is not emphasized in the processes models of crisis and risk communication, and possibly is taken for granted. Even when a certain aspect that is related to crisis communication with the public is presented, such as crisis communication strategies from the Situational Crisis Communication Theory41, linguistic features and linguistic accommodation are not explicitly mentioned as being part of the processes. Some research considered other aspects like number of words, number of sentences and words per sentence58. In other words, when a crisis communication model, like the networked crisis communication model45 and social-mediated crisis communication model59, mentions elements like message form or message strategy, it ignores the linguistic characteristics of the message. The best practices in crisis communication32 introduce general principles of crisis communication, such as strategic planning, proactive strategies & strategic response, and each include sub categories that can be directly related to public communication, e.g “be open and honest”, “communicate compassion” and “provide self-efficacy”. Since speakers’ verbal style also influences how messages are perceived60, we suggest that even if crisis managers will act according to these principles, they should employ certain linguistic styles and consider delivering messages in public accommodated language

Social Computing

“Computational social science is an emerging research area at the intersection of computer science, statistics, and the social sciences, in which novel computational methods are used to answer questions about society”61 (p. 257). Ericson62 argued that social computing refers to “systems that support the gathering, processing and dissemination of information that is distributed across social collectives. Furthermore, the information in question is not independent of people, but rather is significant precisely because it linked to people, who are in turn associated with other people.” Scholars63 stated that social computing represents a new research frontier for information systems. Social computing environments present settings for data collection on a wide variety of aspects for researchers interested in online behavior of individuals, both in natural observations and for controlled experiments.

Behavioral Targeting.

Behavioral targeting (BT), also called online profiling64 or hypertargeting65 uses historical user behavior to predict user behavior and affinities in web applications such as targeting of online advertising, content personalization and social recommendations66. BT is used by online advertisers to increase the effectiveness of their campaigns, and is playing an increasingly important role in the online advertising market67. Through series of experiments, compared to standard run of network advertising, BT advertising was found to be more successful, creating greater utility for consumers from more relevant advertisements and clear appeal for advertisers from increased ad conversion68. User profiling is performed using novel computation techniques66,69, commonly fall inside the social computing paradigm, an approach to analyze and model social behaviors on different media and platforms70. Van Dam & van de Velden71 proposed that social networks, like Facebook, can be “operationalized to gain insight into the individuals connected to a company’s Facebook site” (p. 60). In their study they describe a user profile data collection framework that uses “Facebook insights” (accessed by the admin) and other personal public information on Facebook to cluster users. They propose that their methodology can be implemented into an analytical customer relationship management (CRM) framework aimed at the analysis of customer characteristics that may help improve a firm’s customer management strategies.

Recommender systems.

Ricci, Rokach, & Shapira72 defined Recommender Systems (RS) as “software tools and techniques providing suggestions for items to be of use to a user” (p. 1). They add that since recommendations in most cases are personalized, different users or user groups receive different suggestions. RSs try to predict what the most suitable products or services are, based on the user’s preferences and constrains (learned and collected from users. Many product purchasing sites like Amazon and E-Bay use advanced recommendation engines73, but social networking sites (e.g. Facebook) use RS as well, to “push” relevant social content based on use preferences, actions and texts74.

Recommender systems in Emergency. In the context of emergency, the existing published literature suggests that recommendation systems can be integrated for improved disaster management75, Construction and real estate crisis management76 and supply distribution in emergency77. However, we could not find existing literature of how crisis communication can be aided by RS. More specifically, how crisis messages are selected for individuals or groups of individuals based on some characteristics. Research shows that integrating data obtained from popular social media networking websites significantly can improve results of existing recommendation systems78.

Computational social science in the face of disasters.

Over the past years technologies that rely on citizen sensing have been playing a major role in real life applications, such as public and environmental health surveillance79, and other participatory social activities80,81,82. Purohit, Castillo, Meier & Sheth83 noted that with the explosion in social media and the universal mobile access– researchers have unique opportunities to “extract social signals, create spatial-temporal mappings, perform analytics on social data, and support applications that vary from situational awareness during crisis response, preparedness and rebuilding phases to advanced analytics on social data, and gaining valuable insights to support improved decision making”. (p. 1).

Social computing, analytics, visualization for crisis communication.

In the era of big data analytics and social media, incorporation of business intelligence systems in the organization are very common. These systems are responsible for data processing, analysis and visualization for better decision making and business function. Based on a recently published taxonomy in the domain of text analytics and visualization84, one can find various analytical tasks and visualization tasks with specific aim. The tasks are common text analytical procedures85,86, and include: 1) Text Summarization / Topic Analysis / Entity Extraction, 2) Discourse Analysis; 3) Sentiment (Opinion) Analysis, 4) Event Analysis; 5) Trend / Pattern Analysis; 6) Lexical / Syntactical Analysis; 7) Relation / Connection (Association) and 8) Translation / Text Alignment Analysis. These tasks later serve for visualization procedures for: 1) Region of Interest, 2) Clustering / Classification / Categorization, 3) Comparison, 4) Overview; 5) Monitoring; 6) Navigation / Exploration; 7) Uncertainty Tackling.

Tables 1 & 2 summarize current state of the art of how social computing and text analytical tools can be integrated in the best practices of crisis communication27,32. We focus on the objectives in the processes of crisis and emergency communication27 that occur in different times of the crisis life cycle and have direct association to communication processes with the public. Finally, we describe how computational and analytical tools can be utilized to accomplish these aims.

Table 1: Analytical Tasks in the domain of Text Mining & Analytics for Crisis and Emergency Communication using Social Media

Table 2: Visualization Tasks in the domain of Text Mining & Analytics for Crisis and Emergency Communication

Monitoring and recognition of emerging risk.

Information extraction tools using pre-defined lexicons of crisis related terms87,88, as well trend analysis (e.g. hashtag or term anomaly detection) could be a useful way to spot potential risks in the environment, based on social media feeds and streams, that previously have shown themselves to be valuable sources of real-time information about what is happening in the world89. Social Media feeds can represent a hybrid form of a sensor system that allows for the identification and localization of the impact area of the event90,91. Next, using text visualization techniques, geo-located information can be mapped and depicted in a way a potential risk can be categorized according to its geographical occurrence. As people will explicitly mention different terms related to potential risks, dynamic map would show categorizations of the terms into risk topics, allowing crisis managers to monitor risks.

General public’s understanding of risk.

Public’s knowledge of risk is conducted most of the times through surveys33. However, it can also be inferred from social media discussions. Emergency authorities can, for instance, publish question regarding different issues related to specific risk in their feed (e.g. lifesaving behavior in wild-fire) and later investigate the discussion followed by post publishing. Research shows that social media discussions tend to be topic dependent92,93, especially when the page posts direct questions and asks the general public to discuss an issue. Crisis managers could train text responses over documents that an expert panel would consider as relevant to the original question (e.g. “what is the correct lifesaving behavior during wildfire”), and also classify documents according their answer correctness using Natural Language Processing (NLP)94 and classification algorithms86. Overview level of the public understanding of risk, based on social media discussion, then could be visualized using simple pie charts.

Message development in crisis communication.

Based on the variety of approaches presented above, this aspect can be aided by discourse analysis95, linguistic analysis and natural language processing. Using lexical approach96 and psycholinguistic tools53, crisis managers can analyze messages from different perspectives– from syntactic features of the text and various word meaning categories (e.g. LIWC categories). We propose that integration of such tools would enable to observe whether all pre-designed crisis messages are adapted to the target audience’ communication capacities.

Affected public opining mining.

To gain feedback from the affected public, one should monitor social media and extract signs from citizen who speak and discuss the emergency. Temnikova et al.88 presented a terminological resource, EMTerms, which include over 7,000 terms used in Twitter to describe various crises, classified into 23 information-specific categories (e.g. caution and advice, infrastructure damage, supplies needed or offered, personal updates, safety and security and more). Such resource can assist decision makers monitor different categories of information, and later communicate to the public on the most prominent information. Once information is retrieved, automated text analytical approaches, like opinion mining, can assist in capturing public’s perceptions. Opinion mining refers to the extraction of emotion, appraisal and opinion words that are associated with certain social issue, people or entity (e.g. product, public figure, and event) and the classification of the words into different opinion categories (e.g. positive vs. negative, support vs. against)97. Seeger32 argued that capturing public’s perceptions are important due to the tight association between beliefs and actions. He adds that monitoring public’s risk perceptions and opinion prior and during crisis is essential for crisis response and message adaptation to public’s needs and concerns. This text analysis procedure has various application in a review summarization & classification, market and brand analysis98, political opinion analysis and decision making. Opinion and sentiment classification is performed on a document and sentence levels by extracting relevant features (e.g. single and/or multiple words, emoticons) from the text and applying computational techniques for estimating the overall polarity or direction of the text. The most common methodology involves pre-defined sentiment or opinion lexicons that carry thousands of domain-specific words, or machine learning techniques that use supervised learning for sentiment classification.. In the context of natural/human made disasters, the assessment of sentiment is somehow scarce. Nagy, Valley, & Stamberger99 compared methods for evaluating sentiment in disaster microblogs and explored patterns of change in emotion of the crowd during a technological disaster. Unfortunately, assessment of sentiment towards the general crisis event provides only partial information for crisis communication practitioners regarding crowd opinion, since it is not matched to specific risk or issue, and more

In the case of health crisis and pandemics, however, considerable research is found. For instance, in the case of swine flu pandemic, Salathé & Khandelwal100 used publicly available data from users of online social media and measured spatial-temporal sentiment towards a new vaccine over a period of six months. They further found strong correlation between sentiments expressed online and CDC-estimated vaccination rates by geographical region. This provides good example of how policy makers can use publicly available data to learn about public’s perception regarding risk and its’ related behaviors.

Misunderstanding/Rumors Corrections.

Possibly one of the most researched topics in the domain of disaster computing and social media research during crisis, is information credibility101,102. Castillo et al.102 analyzed information credibility of news propagated through Twitter and suggested that by using automated methods a tweet can be classified with up to 80% precision as being credible or not. Their automatic credibility estimation was done by extracting message-based features (e.g. text length, sentiment ratio in the text, inclusion of hashtag), user-based features, topic-based (e.g. aggregates computed based on message and user based features), and propagation-based features (e.g. depth of a retweet in the network of message spread, initial tweets per topic).

Evaluation and assessment of responses, including the effectiveness of communication.

Similarly to the previous section, evaluation of public responses can be achieved through continuous social media monitoring using opinion mining, to infer on concerns, panics, and the emotional impacts of interactions among social media users103. Recent studies demonstrated capabilities to track changes in sentiments of affected public during natural disasters99,103,104.

Proposed Process of Hyper-targeted Crisis Communication in Social Media (HCCS)

In the above paragraphs, we described how advanced analytical tools can be integrated in the processes and aims of crisis communication. We suggest that the availability of the computational techniques can improve communication with the public by a process of hyper-targeted crisis communication. Figure 1 demonstrates how the data posted and shared through social media is collected for monitoring, analyzed and prepared for a tailor-made crisis communication.

Fig. 1: The Process of Hyper-targeted Crisis Communication in Social Media (HCCS)

In the process, massive amounts of textual user-generated content in social media is continually generated and monitored for crisis or emergency related communication. Once detected, content is collected and transferred to the analytical phase, where it is preprocessed, analyzed according to various text mining analytical methods. The information then is either transferred for reporting where it can be visualized and interpreted or moves to the communication management module. Authorities, crisis managers and designated spokespersons personnel can communicate with the public, using the communication management module, which include a recommender system that proposes matched messages. This sub-system is also responsible for target audience profiling (i.e. hypertargeting), that enables accommodated communication to specific groups in the population. Bi-directional communication is then monitored for matching accuracy and secondary messages in the communication. During the conversation, a crisis messaging recommender system formulates messages based on conversation history and the other available parameters.

Benefits of Targeted Crisis Communication

Automatic categorization of unstructured vital information is of high importance for speeding up disaster management. More precisely, psychosocial information extraction is valuable for decision makers to understand the endurance of the public, public’ psychological needs and psychological risk, using validated theoretical models in the field of disaster psychology105. Being able to capture these aspects, emergency authorities can be more synchronized with population needs and thus more effective in their response to the public during disaster. By integrating disaster related psychosocial aspects in a command and control disaster management systems, they will be in a better position to manage the situation and speed up recovery.

Successful detection of language choice patterns from social media content may assist in guiding the authorities and service providers to respond on the same communication “channels” of the public, and enhance responsiveness and interactivity. This can further lead to a more cooperative public and enhanced public morale. It is our assumption that such focused messaging may not only improve the reception of the message, but also contribute to the ensuing behavior or compliance which is critical in disasters.

Limitations of the present review and currents challenges

One should remember that beyond text, additional forms of data are published on social media, sometimes far more influencing, since pictures (regular photo or meme) may generate more engagement than other forms of data (including text and video)106. Research documents applicable tools for multimodal analysis of social media content, that include both textual and visual data, e.g. Flicker photos, YouTube videos and more107. Thus, more precise public monitoring could be accomplished when integrating data from different modalities and content qualities, as adjacent task in the crisis communication processes. The above literature focused mainly on text that appears in the social media, that can be extracted and analyzed. As for now, some social media platforms offer easy means of extracting data, like the Twitter Streaming API108. One limitation in social media analysis is the inaccessibility to Facebook public feed API, which is restricted to a limited set of media publishers. This limitation is restricting research institutes and companies to obtain public posts, in a similar way that is available in Twitter. It is possible, though, to extract data from Fan Pages and Groups using publically available applications, like NetVizz109.

Decision makers should not solely rely on text analytics in social media when doing crisis communication. Though social media is very popular and has very high penetration rate11, some social and age groups in the population are not connected to the internet110. As this population tends to receive the information and guidelines during real time emergency via TV, radio, newspaper and word-of-mouth -the instructions will still need to use traditional means of mass communication..

Despite recent anecdotal reports indicating that authorities (e.g. Home-front command) increase their presence in the social media and continuously interact with the public in times of calm and emergency, still authorities prefer to communicate with the public in non-interactive means. This was previously mentioned as an obstacle for crisis communication111 in light of the raising of social media .Nonetheless, decision makers should not solely rely on methods of text analytics and data mining in social media when doing crisis communication and follow a well-organized risk and crisis communication plan34.

It is almost impossible not to consider privacy issues when discussing targeted communication112. Collecting information about the behavior of social media users, for research or commercial purposes, is considered invasive by the public as well as inappropriate113. Recently, the use of Facebook as a research platform for massive social experiment114, was criticized for not passing the ethical board and not providing informed consent to the participants. Conversely, Facebook advertising system is using profile information and interests (extracted from activity patterns of the users), to deliver targeted messages. Hence, authorities have to deal with this issue using sound legal advice and should address the privacy issues in their communications with the public to build trust and credibility.

Recommendations

Both user profiling (i.e. behavioral targeting) and recommender systems are closely related. In both processes, user preferences are used for content recommendation. However, the application of behavioral-targeted recommendation system in the field of crisis communication is novel and deserves future studies. We propose that behavioral-targeted recommendation systems in the domain of crisis communication would be applied on two levels; public level and decision maker level. On the public level, personalized and adapted crisis messages would pop-up or appear in popular websites and social media based on two possible parameters: 1) the written content people provide on these sites (e.g. users’ public posts, reviews, and participation in talkbacks; 2) user behavior on site – such as “like”/”share’ or “re-tweet, or other forms of ratings. This approach would be effective if the user is active and engaged, but also may be relevant for passive users that mainly consume content rather than commenting on it. This proposal will be feasible in social media platforms which allow the tracking of users or has an agreement for data sharing with authoritative bodies. On the decision maker level, designated spokespersons would be assisted by the messaging recommender system to adapt their linguistic style to the user who approaches them (or vice versa) thus “tailoring” the response and assisting people in real-time to get the appropriate help, directions or support.

While certain online platforms for communication with the public in emergency were proposed111,115 they all significantly lack the user-profiling element, that might be in practice, an important factor in communication efforts116. Future web-based or mobile application-based platforms for disaster risk communication should include user-profiling module, based on different parameters extracted from users’ published text and data. We suggest social media management tools29 as suitable platform for crisis communication, as some of the tools enable the integration of extensions and apps that assist in social media data extraction, analytics and interpretation.

Conclusions

In very fast pace, social media have acquired a prominent role in media and our daily life71. During crisis and emergency, people tend to approach social media not only because of the need for quick information, but also due to the human tendency for storytelling, which allows people to experience their lives as coherent, orderly and meaningful. It is what makes people’s life more than a blooming, buzzing confusion117. Communication with public during emergency is critical for successful emergency management118 life saving, rescue and recovery. On the other hand , one should take into account that 2.08 billion people world-wide are social media users11 and significant number of people are expected to participate in the online convergence, posting massive amount of user-generated content making it an almost impossible web of information. Using state of the art computational tools makes this mission possible. Being one of the fundamental tools of emergency management118, crisis and risk communication play an important role in mitigating, or exacerbating, the psychological and behavioral reactions to critical incidents and disasters. Thus the task of continues monitoring of the social web for crisis related information can significantly improve the efforts of emergency management. This is the reason for officials to be eager to exploit social media content to gain insight from the public for the optimization of risk and crisis communication119. Risk and crisis communication’ best practices are well documented and include various tasks during different crisis stages (e.g. understanding public’s characteristics, monitoring emerging risk, feedback from affected publics etc.). These aims and practices can be improved and become efficient when utilizing linguistic computational tools that can quickly assist decision makers in designing emergency campaigns, or/and managing communication with the public during emergency. Officials should also remember that the most effective communication are those designed for a specific audience33. Research shows that interpersonal communication that is linguistically matched between the communicators is not only more successful, but also reflects our natural tendency to adjust ourselves to the listener. Finally, decision makers and crisis managers need to acknowledge the potential of the massive generated textual information published during times of emergency in the social media. This knowledge is not only beneficial for situational awareness but also for user profiling, which in our case, is not intended for marketing purposes. Behavioral analyzed information from text posted on social media can leverage targeted communication during crisis, by automatic target audience characterization and adapted, psycholinguisticly matched risk message preparation. Thus, as we keep facing major disasters and emergencies that have became more frequent during the last decade, governments can be more effective in transmission and dissemination of warning messages or/and survival information, better manage different public reactions triggered by the crisis, gain credibility from the public, and improve public cooperation during emergencies.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

INTRODUCTION

The competence of responders to international disasters is one of the cornerstones for successful program interventions. Hence, building capacity for responders before deployment is an investment to their organizations.1,2 International relief efforts depend heavily on volunteers when responding to international disasters, and volunteers look for structured training programs as an opportunity to build their capacity and to be better prepared.3 The total percentage of volunteer responders working with non-governmental organizations (NGO) in response to international disasters and complex humanitarian emergencies is not well documented in the literature. Adequately trained responders not only provide better service, but also present a smaller risk for organizations and a higher level of operational efficiency.

When responding to international disasters, most health care professionals face austere environments with limited resources. Some volunteers are organized in advance and have been trained and directed to respond through government programs (e.g., Disaster Medical Assistance Teams [DMAT], Medical Reserve Corps [MRC]) and private sector efforts (e.g., American Red Cross, Orthopedic Trauma Association Mass Casualty Teams [OTAMCT]).4,5,6 There are also “spontaneous volunteers” who show up ready to help but lack organization, identification, credentials, and, ultimately, utility. Rather than assisting in the emergency efforts, the presence of many uncoordinated volunteers can actually impede effective emergency responses and create a liability to organizations and to themselves.2 The most vulnerable responders are novice spontaneous volunteers who lack the experience going on their own instead of through an organization. They may find themselves in situations that require heightened security awareness, cultural sensitivity, and behavioral mental health skills. The better prepared a volunteer is to fill his or her role, the smaller the chance of unintended harm. Volunteers need to know not only what they should do but also what they should not do. As part of this strategy, organizations should make available volunteer position descriptions, a code of conduct, and appropriate training courses and exercises.7

In addition, some volunteers need specialized training in caring for pediatric patients or patients who are suffering from mental health issues. Children are often the worse victims of disasters, with the under-5 mortality rate approaching 13% in a typical 5-year war.8,9 They require specialized medical care as well as intense psychological support.10

The exact number of responders to international disaster and Complex Humanitarian Emergencies (CHEs) is not well documented in the literature, nor is the percentage that have received formal structured training before actual response. Many organizations do not formally train their own personnel before deployment, let alone volunteers.11 This is perhaps the case because identification and characterization of various structured training programs and opportunities available to responders to international disasters is lacking. The objective of this manuscript was to identify and compile a list of the various structured training programs available for responders to international disasters and complex humanitarian emergencies, highlighting their diverse scopes and characteristics.

METHODS

An environmental scan was conducted through a peer-reviewed literature search of PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane databases, and an open Internet search for training program websites. The landscape literature search was conducted by combining the search terms “international,” “disaster,” “complex humanitarian emergencies,” “training,” and “humanitarian response.” All searches were conducted from January2, 2013 to September 12, 2013. Initially, 681 citations were retrieved from the above named search engines. Screening by titles narrowed the focus to 165 articles and a further screening by abstract led to 40 articles, of which a full text review revealed 14 articles that contained information regarding training programs for responders to international disasters and CHE.8,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22

RESULTS

A total of 14 peer-reviewed articles mentioned or described eight training programs, while open Internet search revealed 13 additional programs. In total, twenty-one training programs were identified as currently available for responders to international disasters and CHE.

Each of the programs identified has different goals and objectives, duration, expenses, targeted trainees and modules. Seven programs (33%) are free of charge and four programs (19%) focus on the mental aspects of disasters. The mean duration for each training program is 5 to 7 days. Fourteen of the trainings are conducted in multiple locations (66%), two in Cuba (9%) and two in Australia (9%). The cost-reported in US dollars- ranges from $100 to $2,400 with a mean cost of $480 and a median cost of $135. Most of the programs are open to the public, but some are only available by invitation, such as the International Mobilization Preparation for Action (IMPACT) and the United Nations Humanitarian Civil-Military Coordination (UN-CMCoord) Field Course. The target audience for IMPACT should satisfy three conditions: 1) have met the established criteria (technical competency in an international emergency response context in one of the “core functions”, “field experience”, and available for four-week voluntary deployment), 2) successfully completed screening interviews, and 3) completed World of Red Cross (WORC) training program.23 UN-CMCoord Field course participants should satisfy the following five conditions: 1) completed the UN-CMCoord course, 2) have a minimum of five year experience with civil-military coordination in the humanitarian assistance, 3) fluency in oral and written English; 4) fluency in other UN language and 5) currently performing a task that require interaction with the Military.24

Table 1 displays the twenty-one structured training programs (in alphabetical order), along with the organizer, location(s), cost, duration, and year established.

Name

Organizer

Type of Participants

Location

Cost (USD)

Duration

Year Established

ADPC

NI

Government officials

responsible for disaster management plan and policy; personnel involved in defense forces

and emergency servicesThailand

$2,275-3,175

2 weeks

1986

CDAC

Australia Red Cross

Red Cross staff,

volunteers; anyone interested in building international capacityAustralia

$650-920

2 days

NI

CDHRTP

University of Toronto Koffler Scientific Reserve

Anyone interested in humanitarian work

Canada

$2,080

2 weeks

NI

CHART

ICRC

Civilian and military disaster planners

Multiple

NI

5 days

1993

CHR

Cuba

Not reported

Cuba

Free

Rolling

2005

DHMP

American Red Cross, FEMA

Professionals from diverse mental health backgrounds

Multiple

$500

2 days

1990

DMTC