Abstract

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. Screening has been shown to be effective in reducing colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal occult blood tests are all recommended screening tests that have widespread availability. Nevertheless, many people do not receive the evidence-based recommended screening for colorectal cancer. Additional stool-based methods have been developed that offer more options for colorectal cancer screening, including a variety of fecal DNA tests. The only fecal DNA test that is currently available commercially in the United States is ColoSure(TM), which is marketed as a non-invasive test that detects an epigenetic marker (methylated vimentin) associated with colorectal cancer and pre-cancerous adenomas. We examined the published literature on the analytic validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility of ColoSure and we briefly summarized the current colorectal cancer screening guidelines regarding fecal DNA testing. We also addressed the public health implications of the test and contextual issues surrounding the integration of fecal DNA testing into current colorectal cancer screening strategies. The primary goal was to provide a basic overview of ColoSure and identify gaps in knowledge and evidence that affect the recommendation and adoption of the test in colorectal cancer screening strategies.

Application: Screening

Background

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) screening

Screening by colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and fecal occult blood testing has been shown to prevent colorectal cancer (CRC) and to reduce mortality through the detection and removal of pre-cancerous lesions and through the detection of CRC in its early stages [1] [2]. Indeed, CRC incidence and mortality have been decreasing since 1985 [2] [3]. Research suggests that CRC screening may be responsible for approximately half of the declines [2]. However, uptake of CRC screening recommendations in the U.S. is not optimal. In 2008, only about 62% of men and women aged 50-75 years reported getting the most commonly recommended CRC screening tests, a percentage that varied from 49-75% among states [4].

Several tests are available to identify colorectal cancer and pre-cancerous polyps in asymptomatic individuals. Colonoscopy visually inspects the interior walls of the entire rectum and colon. Performance characteristics (such as sensitivity and specificity) of new tests are commonly evaluated in comparison with colonoscopy [1] [5]. Flexible sigmoidoscopy involves a more limited visual inspection of the distal colon and rectum. Fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs), which include conventional guaiac FOBT, high-sensitivity guaiac FOBT, and fecal immunochemical tests (FITs), chemically detect small amounts of fecal blood (which can originate from pre-cancerous and cancerous colorectal lesions). CT colonography (i.e., virtual colonoscopy) and double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) are additional tests, offering enhanced x-ray images of the interior rectum and colon to aid in detecting abnormalities.

Fecal (stool) DNA tests have been under continuous development over the past several years. These tests are designed to detect in stool samples any number of DNA markers shown to be associated with CRC. ColoSure™ is the latest example of a clinically available stool DNA test.

Clinical Scenario

The clinical scenario for fecal DNA testing in general is most often presented as colorectal cancer screening in average-risk individuals.

A technical brochure for ColoSure [6] states that:

“ColoSure is not intended to replace a colonoscopy in those patients who are willing and able to undergo the procedure. Additionally, while it may be used adjunctively or in patients noncompliant with screening recommendations, it is not a screening tool for individuals at increased risk for developing disease.”

Test Description

ColoSure™ (Laboratory Corporation of America, https://www.labcorp.com ) is currently the only commercially or clinically available fecal DNA test marketed for CRC screening in the U.S. The at-home test requires that patients collect and mail one whole stool sample. The test was developed by the Laboratory Corporation of America (LabCorp), which required licensing intellectual property from Exact Sciences Corporation ( www.exactsciences.com ). As a laboratory-developed (“home-brewed”) test, ColoSure is not subject to regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and has not obtained FDA clearance or approval.

What is the theory behind stool DNA testing? Colorectal cancer cells, which are shed into the feces, are known to have several genetic alterations which offer an array of molecular targets for DNA-based stool testing for both pre-cancerous and cancerous lesions [7] [8]. Consequently, fecal DNA has been explored for its potential as a non-invasive CRC screening methodology.

ColoSure is a single-marker test that detects methylation of the vimentin gene. Increased DNA methylation in the promoter region of genes is an epigenetic change that is common in human cancers, including colorectal cancer [9] [10]. Vimentin is a protein characteristically expressed in cells of mesenchymal origin, such as fibroblasts, macrophages, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. Studies have demonstrated that the vimentin gene is not (or rarely) methylated in normal colonic epithelial cells, but is methylated in colorectal cancer and adenomas [11] [12] [13]. Aberrant methylation of vimentin has been detected in 53-83% of colorectal cancer tissue, 50-84% of adenoma samples, and 0-11% of normal colon tissue samples [11] [12] [13] [14] [15], though one preliminary study detected methylated vimentin in 29% of normal colon tissue [16].

ColoSure requires a prescription for testing. It is currently available from two sources: LabCorp [17] and from DNA Direct’s Genomic Medicine Institutes (which only offers referrals to physicians who can prescribe the test) [18] [19].

Public Health Importance

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is currently the third leading cancer diagnosed in the United States, where the lifetime risk is approximately 5% in the general population [3] [7]. According to the U.S. Cancer Statistics, ~143,000 cases of CRC occurred in the U.S. in 2007 [20]. CRC is also the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with approximately 53,000 deaths occurring in 2007 [20]. Approximately half of colorectal cancers are diagnosed at a late stage, when survival is poorer [4].

The most effective way of reducing the risk of developing CRC and of reducing CRC mortality is early detection and removal of pre-cancerous or cancerous lesions. It is thought that the natural history of CRC development takes between 10 and 20 years, offering an excellent opportunity for early intervention [1] [21].

Three types of tests (colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and fecal occult blood tests) are currently recommended as evidence-based CRC screening options by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [1]. However, only a modest percentage of adults meet the recommended CRC screening guidelines [4].

Stool-based DNA tests are suggested by some experts as another option for CRC screening. However, these tests are under rapid development and research to establish analytic validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility within the general (average-risk) population is needed before any fecal DNA test can be integrated into current CRC screening strategies. We now examine these factors for the ColoSure test based on the current literature.

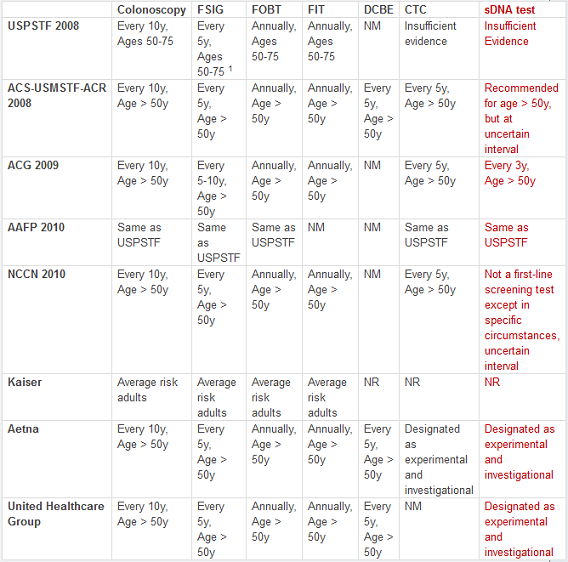

Published Reviews, Recommendations and Guidelines (see Table 1 below)

Important Note: The following groups considered fecal DNA testing in general, but largely based their recommendations and guidelines on published research relevant to stool DNA tests that are no longer commercially available.

Systematic evidence reviews

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) commissioned an evidence report/technology assessment on enhancing the use and quality of CRC screening [22] [23]. They found no reliable data among the included studies concerning the trends in use or quality (evidence of misuse, overuse, or underuse) of fecal DNA testing.

A systematic evidence review was performed that guided the current recommendations on CRC screening by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [5] [24] (see subsection below).

Recommendations by independent group

Fecal DNA testing was considered by the USPSTF in its most recent recommendation statement on CRC screening (see Table 1 below). The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to evaluate the benefits and harms of this kind of testing as a screening modality for CRC (I statement) [1].

Guidelines by professionalgroups (in order by year of publication)

A Joint Guideline was published in 2008 by the American Cancer Society, the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology (ACS-USMSTF-ACR) [25] . Stool DNA testing in general was recommended for those aged 50 years or older, but the testing interval could not be determined. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) published CRC screening guidelines, in which a weak recommendation (Grade 2B) was made for stool DNA testing every 3 years for persons 50 years of age or older [26]. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) [27] published recommendations in 2010, which deferred to the analysis and findings of the USPSTF. Also in 2010, the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [28] stated that: 1) stool DNA testing is not currently considered a first-line screening test except in specific circumstances; and, that 2) the testing interval is uncertain.

Health Plan/Payer policies

CRC screening guidelines have been issued by Kaiser Permanente [29], Aetna, Inc. [30], and United Healthcare Group [31][32], all of which describe fecal DNA screening as experimental and not recommended for use.

A summary of all mentioned recommendations and guidelines appear in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Routine Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines and Recommendations for average-risk adults.

CTC = CT colonoscopy; DCBE = double-contrast barium enema; FIT = fecal immunochemical test; FOBT = fecal occult blood test; FSIG = flexible sigmoidoscopy; sDNA = stool DNA.

NM = not mentioned; NR = Not Recommended. 1 In combination with high-sensitivity FOBT every 3 years.

Evidence Overview

We performed literature searches (through PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE) that included search terms such as “vimentin”, “fecal DNA”, and “colorectal cancer”.

Analytic Validity: Test accuracy and reliability in measuring methylated vimentin (analytic sensitivity and specificity).

Summary: the analytic validity of the ColoSure test could not be determined from the identified research.

Clinical Validity: Test accuracy and reliability in detecting colorectal cancer or adenomas (clinical sensitivity and specificity; predictive value).

Table 2. Summary of the published case-control studies relevant to ColoSure that reported measures of clinical validity using fecal DNA testing in selected populations

| Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Study | Marker(s) | CRC | Adenoma1 | ||

| Chen 2005 [11] | Methylated vimentin | 46% (43/94) | — | 90% (178/198) | |

| Itzkowitz 2007 [38] | Methylated vimentin | 73% (29/40) 2 | — | 87% (106/122) 2 | |

| (Phase 1a) | DY | 65% (26/40) 2 | — | 93% (113/122) 2 | |

| Methylated vimentin or DY | 88% (35/40) 2 | — | 82% (100/122) 2 | ||

| Itzkowitz 2008 [37] | |||||

| (Phase 1b) | Methylated vimentin | 81% (34/42) 2 | — | 82% (198/241) 2 | |

| DY | 60% (25/42) 2 | — | 85% (205/241) 2 | ||

| Methylated vimentin or DY | 86% (36/42) 2 | — | 73% (176/241) 2 | ||

| (Combined Data) | Methylated vimentin | 77% (63/82) 2,3 | — | 83% ( 301/363) 2,3 | |

| DY | 48% (39/82) 2,3 | — | 96% (348/363) 2,3 | ||

| Methylated vimentin or DY | 83% (68/82) 2,3 | — | 82% (298/363) 2,3 | ||

| Ahlquist 2008 [14] | Test SDT-2 (point mutations on K-ras , scanned mutator cluster region of APC , methylated vimentin ) | 58% (7/12) 2 | 46% (47/103) 2 | Not calculated | |

| Baek 2009 [36] | mMLH1 | 30% (18/60) | 12% (6/52) | 100% (37/37) 4 | |

| Methylated vimentin | 38% (23/60) | 15% (8/52) | 100% (37/37) 4 | ||

| MGMT | 52% (31/60) | 37% (19/52) | 86% (32/37) | ||

| All three markers (combined) | 75% (45/60) | 60% (31/52) | 86% (32/37) | ||

| Li 2009 [33] | Methylated vimentin | 41% (9/22) | 45% (9/20) | 95% (36/38) | |

DY = refers to a specific test for DNA integrity.

— Not measured.

1 Refers to adenomas ≥ 1 cm.

2 We calculated the numerator using data presented in the article.

3 In the study, sensitivity and specificity were calculated using optimal cutpoints based on the combined dataset (Phases 1a + 1b).

4 We calculated specificity using data presented in the article.

Summary: the clinical validity of methylated vimentin as a biomarker for CRC screening remains to be determined in a general (average-risk) screening population. This is re-iterated in the LabCorp technical review for the ColoSure test [6], which states that: “The detection rates for general population screening have not been determined.”

Clinical Utility : Net benefit of test in improving health outcomes

Summary: the clinical utility of ColoSure (or methylated vimentin in general) in an average-risk screening population could not be determined from the identified research.

Final important note:

Fecal DNA tests are under rapid development. Exact Sciences Corporation has developed several approaches to fecal DNA testing for colorectal cancer screening over the past few years. Previous tests were replaced sequentially with newer versions, which differed in laboratory methodology or tested for a different panel of DNA markers. The current ColoSure test is a replacement of a version of the PreGen-Plus™ test (Laboratory Corporation of America), which has been discontinued. Exact Sciences recently reported results from a validation study of its newest stool-based DNA test for colorectal cancer screening, named Cologuard™. The panel that was presented included methylated vimentin as one of the tested markers [42] [50] [51]. Exact Science is currently funding a case-only study [ NCT01260168 ] to determine the sensitivity of this new multi-marker DNA panel in CRC cases. The company is planning to pursue FDA approval for Cologuard in 2012 [50]. These developments likely mean that ColoSure will be replaced in the future by this, or other, tests.

Concluding remarks:

In order to consider integrating fecal DNA testing into current CRC screening strategies, additional research is needed to establish analytic validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility within the general (average-risk) population. The estimates of DNA marker sensitivity and specificity found from small case-control studies should not be extrapolated to make any estimates of the performance of methylated vimentin or ColoSure in the general population.

In addition, the ongoing development and refinement of stool DNA tests presents some difficulty for the integration of these tests as a CRC screening approach. Currently, only one fecal DNA test is commercially available in the U.S., a test that will likely be replaced by a newer version for which FDA approval will be sought.

Other critical matters must also be addressed, including the determination of cost-effectiveness, optimal testing intervals, and strategies for the follow-up evaluation of patients who test positive on a fecal DNA test. Moreover, the willingness of individuals from the general population to adopt fecal DNA test protocols and future screening recommendations is a vital consideration. All of these factors will be crucial in affecting the impact of fecal DNA testing on the overall CRC screening paradigm and on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality.

Links (not referenced above)

Last updated: March 14, 2011

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for invaluable input and guidance on the content of this manuscript: Dave Dotson, Ralph Coates and Katie Kolor (Office of Public Health Genomics, CDC); Lisa Richardson and Djenaba Joseph (Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC); and Evelyn Whitlock, Beth Webber, and their colleagues (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research).

Funding information

This work was funded by the Office of Public Health Genomics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Disclaimers

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The information provided in this manuscript does not constitute an endorsement of ColoSure(TM) or of any fecal DNA test by the CDC nor the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) of the U.S. government. No endorsement should be inferred.

The CDC does not offer medical advice to individuals. If you have specific concerns about your health or genetic testing, we suggest that you discuss them with your health care provider.

sergio stagnaro

Colon Cancer screening? Why not Colon Cancer Primary Prevention? — Some years ago, the health secretary, John Reid, announced a national screening programme for bowel cancer, introduced in England from April 2006 (1). Unfortunately, however, such screening was carried out in “all” individuals over 40 years old, and was based as usually on faecal occult blood testing, which looks for blood in stool samples, and flexible sigmoidoscopy, which could allow careful examination of the bowel. I foresaw that also that screening would be resulted an expensive flop, like that based on CT scanning, since World Health Authorities, in England as well as in Italy, overlook the real existence of Oncological Terrain-Dependent, Inherited Real Risk, e.g., of bowel cancer (2). In fact, I described formerly a lot of biophysical-semeiotic constitutions, among them oncological constitution (2, 6-9) As regards bowel cancer primary prevention, I can state what recently wrote on the “clinical” war against gastric cancer (4, 9), wherein I illustrated my personal “Weltanshauung”, based on 55 year long clinical experience, illustrating a clinical sign: Berretti’s Sign. Really, screening, even correctly, as well as rationally implemented, i.e., exclusively in individuals affected by both Oncological Terrain-Dependent Inherited Real Risk, is remarkable and price-worthy, but primary prevention is better for people (5, 6-13). In conclusion, aiming to defeat Colon Cancer we need a clinical tool, which allows us to bedside recognize individuals involved by real inherited risk, to enrol in primary prevention .Sergio Stagnarowww.semeioticabiofisica.it References1) Mayor S. England to start national bowel cancer screening programme BMJ 2004;329:1061 (6 November), doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7474.1061-a 2) Stagnaro Sergio, Stagnaro-Neri Marina. Introduzione alla Semeiotica Biofisica. Il Terreno oncologico. Travel Factory SRL., Roma, 2004. https://www.travelfactory.it/semeiotica_biofisica.htm 3) Stagnaro S., Stagnaro-Neri M., Le Costituzioni Semeiotico- Biofisiche.Strumento clinico fondamentale per la prevenzione primaria e la definizione della Single Patient Based Medicine. Ediz. Travel Factory, Roma, 2004. 4) Stagnaro S. Oncological terrain plays a paramount role in the war against gastric cancer. https://www.biomedcentral.com/1471- 230X/4/28/comments#87454 5) Stagnaro S., Stagnaro-Neri M., La Melatonina nella Terapia del Terreno Oncologico e del Reale Rischio Oncologico. Ediz. Travel Factory, Roma, 2004.6) Stagnaro Sergio. Reale Rischio Semeiotico Biofisico. I Dispositivi Endoarteriolari di Blocco neoformati, patologici, tipo I, sottotipo a) oncologico, e b) aspecifico. Ediz. Travel Factory, https://www.travelfactory.it, Roma, Luglio 2009.7) Stagnaro Sergio. Colon Cancer Oncological Terrain-Dependent Inherited Real Risk. Ann. Int. Med. (15 April 2009), https://www.annals.org/cgi/eletters/150/7/4658) Stagnaro Sergio. Single Patient Based Medicine: its paramount role in Future Medicine. Public Library of Science. https://www.plosmedicine.org/annotation/listThread.action?inReplyTo=info:doi/10.1371/annotation/0e440745-6bfb-4690-a0c9-92b77057b539&root=info:doi/10.1371/annotation/0e440745-6bfb-4690-a0c9-92b77057b539 9) Sergio Stagnaro. Segno di Berretti: Diagnosi Semeiotica-Biofisica-Quantistica del Cancro Colon-Rettale, ad Iniziare Dal Reale Rischio Congenito. https://www.altrogiornale.org, 9 aprile 2010. https://www.altrogiornale.org/news.php?extend.598310) Simone Caramel and Sergio Stagnaro (2011) The role of glycocalyx in QBS diagnosis of Di Bella’s Oncological Terrain – https://www.sisbq.org/uploads/5/6/8/7/5687930/oncological_glycocalyx2011.pdf12) Simone Caramel and Sergio Stagnaro (2011) Quantum Biophysical Semeiotics of Oncological Inherited Real Risk of Myelopathy: The diagnostic role of glycocalyx. https://www.sisbq.org/uploads/5/6/8/7/5687930/qbs_myelopathy_glycocalyx_english.pdf13) Simone Caramel and Sergio Stagnaro (2011) Quantum Biophysical Semeiotics and mit-Genome’s fractal dimension Journal of Quantum Biophysical Semeiotics, 1 1-27,https://www.sisbq.org/uploads/5/6/8/7/5687930/joqbs_mitgenome.pdf