Notice of Correction

7 January 2016: PLOS Currents -. Correction: Thiol-disulfide Oxidoreductases TRX1 and TMX3 Decrease Neuronal Atrophy in a Lentiviral Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. PLOS Currents Huntington Disease. 2016 Jan 7 . Edition 1. doi: 10.1371/currents.hd.30bdfed3d88457fd605cb8f95fba29b5. View Correction.

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a progressive autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by a trinucleotide CAG repeat expansion in exon-1 of the huntingtin gene (HTT)1. Disease onset is typically in early to mid-adult life with a range from childhood to advanced age. Clinical signs of HD include involuntary movements, psychiatric problems and cognitive decline. Motor signs of HD result largely from dysfunction and loss of neurons in striatum and cerebral cortex2,3. Treatments that delay onset or progression of human HD have yet to be developed.

Trinucleotide-repeat expansion within the HTT gene results in expression of a polyglutamine-expanded mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT). Full-length soluble mHTT undergoes enzymatic cleavage to generate soluble N-terminal mHTT polyglutamine containing fragments4,5. Mutant huntingtin N-terminal fragments exist as monomers, soluble oligomers and larger insoluble aggregates6. Soluble N-terminal mHTT fragments are thought to be the main drivers of disease progression7 and mouse models of HD that express these fragments have a rapidly progressive phenotype8. N-terminal mHTT results in HD through accumulation in cells and aberrant interactions with numerous proteins9,10 and possibly direct production of reactive oxygen species11. Genetic therapeutic approaches that decrease mHTT levels offer the possibility of inhibiting downstream disease pathways, reversing the disease process, and are a promising approach for future treatment of human HD12,13,14,15 .

We have previously reported that the toxic N-terminal 171 fragment of mHTT is prone to thiol oxidation resulting in the formation of soluble oligomeric mHTT; furthermore, these oligomers are degraded more slowly than monomeric mHTT6. Therefore, thiol oxidation within mHTT may contribute to cellular accumulation and toxicity. There is accumulating evidence for the dysregulation of thiol homeostasis in HD. For example, S-nitrosylation of dynamin-related protein 1, a GTPase that mediates mitochondria fission, has been shown to promote degeneration in HD models16. Another study in cultured HD cells showed increased thiol oxidation of peroxiredoxin 1, a protein involved in removal of hydrogen and lipid peroxides17. Furthermore, there are increased levels of copper and iron in mouse HD brain, which in unbound form, can promote thiol oxidation1819,20.

Thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase enzymes mediate protein repair and folding processes. They share a common C-X-X-C catalytic sequence within a thioredoxin-type domain that is required for enzymatic activity and they reduce disulfides by forming a catalytic-site disulfide which is then reduced by an external electron donor21. These enzymes differ in cell location, protein substrates and mechanism of reactivation. Thioredoxins are small thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases involved in repair of oxidatively damaged thiols and redox regulation of cell-signaling pathways via thiol switches22,23. Glutaredoxins have thiol reductase and deglutathioylation activity; they are required for normal mitochondrial function and protection against neurodegenerative processes24,25,26. Protein-disulfide isomerases are another group of enzymes with a thioredoxin domain; they are located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and other compartments where they regulate a large number of processes via disulfide exchange reactions27. Collectively, these oxidoreductases regulate protein folding in the cell secretory pathway, modulation of activity within cell signaling pathways, and repair of oxidatively-damaged nuclear, cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins (reviewed24,28).

Mutant huntingtin undergoes a number of post-translational modifications. Phosphorylation status of serine 13 and 16 within the N-terminus of huntingtin protein is a critical determinant of HD29. Furthermore, acetylation of mHTT lysine 444, down-stream of the glutamine expansion, promotes mHTT clearance by increasing trafficking to the autophagosome30. These post-translational modifications suggest potential therapeutic approaches for modifying HD proximally at the level of mHTT. We have reasoned that there may be a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase that has protective effects by decreasing levels of N171 mHTT, possibly by direct activity on mHTT protein. We therefore undertook a study to seek a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase with mHTT lowering effects in HD cells that we could test in HD mice. We found that thioredoxin 1 (TRX1) and thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 3 (TMX3) both decreased levels of mHTT in cells but did not find evidence for a direct interaction with mHTT. Using a lentiviral mouse model expressing N171 mHTT31, we found that TRX1 and TMX3 decreased striatal neuronal atrophy. Findings support a modulatory role of TRX1 and TMX3 in these HD model systems.

Materials and Methods

Materials: Mouse anti-huntingtin (HTT) (MAB5374) was from Chemicon, and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (AC40) from Sigma. Unless otherwise stated all chemicals were from Sigma.

Primary screen for mutant HTT protein lowering thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases: COS-1 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37⁰C and 5% CO2. For experiments cells were grown in 12-well plates and transfected with plasmid(s) using lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) and reduced serum medium (OPTI-MEM®-1; Life Technologies) at 70-80% confluency using standard procedures. N171-40Q was in pcDNA1 vector and those encoding thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases were in pQE-TRiSystem vector (Qiagen) and expressed with a polyhistidine tag. Gene accession numbers are: NM_001118890.1, NM_016066.4, NM_006541.4, NM_016417.2, NM_001080476.2, NM_001080516.1, NM_001164478.1, NM_003329.1, NM_012473.3, NM_019022.3, NM_021156.3, NM_005742.3, NM_015051.2, NM_004261.3 and NM_080430.2. For plasmids encoding N171-40Q and the thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases 830 ng of each plasmid DNA was used. We co-transfected with plasmids encoding N171-40Q and GFP as a control. Cells were lysed 48 hours after transfection and levels of soluble N171-40Q and actin were measured by Western blot analysis (see below). Actin normalized values were then determined.

Secondary screen for mutant HTT protein lowering thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase: To provide a robust control for each candidate proteins enzymatic activity, we expressed as a control the same protein but with mutation of active-site residues that blocks activity. Thiol-disulfide oxidoreducases have a C-X-X-C active-site and share a common catalytic mechanism. PDIA6 has two C-X-X-C motifs while the others have one. In one study mutation of the N-terminal cysteine within this motif completely blocked enzymatic activity while mutation of the lower cysteine inhibited activity by 90% [32]. Therefore, we replaced the N-terminal active-site cysteine with serine to generate enzymatically inactive control proteins. We generated constructs expressing enzymatically inactive TRX1, TMX3, GLRX1, PDIA6 and FLJ44606 using QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) for use as a specific control for each candidate test protein. Constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. COS1 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding active or inactive thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase, and then N171-40Q levels determined by Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis: For cell culture experiments, cells were washed in cold PBS then lysed directly in lysis buffer [20 mM TRIS (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1% Triton-x100 and protease inhibitor cocktail]. Thirty µg protein samples were resolved by reducing SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF, blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween (TBS-T) at room temperature for 1 hour then incubated with anti-HTT (MAB5492 – 1:2000 dilution) and anti-actin (AC40 – 1:2000) overnight at 4⁰C. After the primary incubation, membranes were washed 4 times for 10 minutes in TBS-T and incubated with goat polyclonal to mouse IgG HRP (Abcam, 1:2000 dilution) at room temperature for an hour. Then membranes were washed again and placed in Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) before imaging with a CP1000 Film Processor (AGFA). Image J software (NIH) was used to quantify band density. Total HTT protein levels were determined by the ratios of the values for HTT and β-actin. For mouse studies, mice were anesthetized and perfused with cold-heparinized 0.9% (w/v) saline. Brains were sectioned frontally at a 1 mm interval then two sections were taken at the level of the injection site, striatum dissected and then frozen on dry ice before storing at -80C. Brains were homogenized in lysis buffer which were then incubated on ice for 5 minutes then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 16 000 x g and 4⁰C. Protein concentrations were determined then Western blot analysis performed as described above.

N171 HTT protein TRX1 interaction experiment: We used a previously described approach to test whether N171 mHTT is a direct substrate of TRX133,34. In brief, a variant of TRX1 with a mutation of the lower cysteine residue within the CXXC active-site motif is used to trap the catalytic disulfide-linked heterodimer with the substrate protein. Heterodimers can be detected by non-reducing Western blot analysis. DNA encoding N171-40Q, TRX1 and mutant TRX1 (mTRX1) was sub-cloned into the bacterial expression vector pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare). Proteins were expressed in bacteria, purified using a GST column, then GST removed by cleavage with PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare) as previously described6 . The purified protein was buffer exchanged into 50 mM Tris (pH 7.0) and 150 mM NaCl. N171-40Q was incubated with TXN or mutant TXN at room temperature for one hour; 50 mM N-ethylmaleimide was then added to block free thiols and the samples were then resolved by reducing or non-reducing SDS-PAGE and proteins detected by western blot analysis.

Mouse husbandry: All procedures and euthanasia methods were approved by the University of Wyoming Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were also in accordance with NIH guidelines. We used female B6/C3H F1 mice purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were maintained under standard conditions of housing and lighting. They were fed a standard cereal-based rodent chow and had ad-libitum access to acidified water (pH 3-4).

Mouse study experimental design: C57BL/6 x C3H F1 female mice were purchased at 5-6 weeks of age. Pre-treatment wheel analysis was at 7 weeks of age. Surgeries were at ~8 weeks of age and mice were sacrificed 6-weeks later based on the studies of de Almeida et al31.

Lentiviral synthesis: We utilized a four-plasmid system for generation of lentivirus expressing N171-18Q and N171-82Q (kindly provided by Dr. Deglon). We subcloned DNA encoding functionally active and inactive versions of TRX1 and TMX3 from pQE-Tri plasmids into the SIN-pGK which uses the phosphoglycerate kinase promoter to drive gene expression. For each virus, the four plasmids were transfected in the molar ratio of 1:1:1:3 for pMDG, CMVΔ8.92, pRSV-Rev and SIN-pGK, respectively. For each T-150 sized flask we used 3.3, 7.2, 2.2 and 7.2 µg plasmid. 293T cells were grown to ~60% confluency in 10% FBS-DMEM and 2 mM glutamine. They were then transfected using jetPrime transfection reagent (Polyplus 114-07) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each T-150 flask we used 1 ml of jetPrime buffer, 20 µg combined plasmids, 50 jetPrime reagent and 36 mls of cell culture medium. Cells were transfected for four hours, washed twice in PBS then the medium replaced. Cells were incubated for a further 72 hours prior to virus purification. Medium was harvested and placed into sterile tubes on wet ice then filtered using a 0.22 µm filter. The filtered supernatant was centrifuged in a SW28 swinging bucket rotor on a Beckman L8-80 centrifuge at 141k x g for 2 hours at 4 degrees C. Supernatant was decanted then tubes were inverted for 4 minutes. The pellet was re-suspended in 300-500 µl of sterile PBS then transferred to a siliconized tube. Samples were then centrifuged at 19000 x g for 60 min at 4 degrees C to concentrate then the pellet resuspended in 50-150 µl PBS by gentle pipetting. The samples were then mixed gently overnight using a tilted horizontal shaker at 4 degrees C. Lentiviruses were quantified in duplicate using a p24 ELISA (Zeptometrix) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lentiviral samples were diluted to 4.0 ng p24 / µl in PBS, stored at 4 degrees C in siliconized tubes and used within 2 weeks of preparation.

Stereotaxic surgery: Mice were anesthetized with 1.75 mg ketamine and 0.25 mg xylazine per 20 grams body weight. After mounting in a stereotaxic frame they were injected at the following coordinates: AP =+0.4; DV= -3.9, then pull up to -3.7 before injection; ML= (all to right), +2.0 if body weight ≥22.5 g, 1.95 if body weight = 20.5-22.4 g, 1.85 if body weight = 19.0-20.4 g, and 1.75 if body weight = 17.5-18.9 g. The needle size used was ½ inch, 31 gauge, and with a 30 degree bevel. Virus was delivered with a peristaltic pump at a rate of 200 nl per minute (2.5 µl over 12.5 minutes). The needle was then left in place an additional 10 minutes before slow removal. Each mouse was injected with 10 ng of p24 equivalents of virus. For testing paired viral injections, different combinations of virus were injected; we used 5 ng of p24 equivalents of each virus which were pre-mixed prior to injection.

Wheel activity analysis: Spontaneous wheel activity was measured before and after surgery. Mice were placed individually in cages containing running wheels for 4 days, running times in both light and dark cycles (12 hours each) were recorded. The first day was used to familiarize mice with the instrument. Data from days 2-4 were used for analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining and brain stereology: Mice were sacrificed by an intra-peritoneal overdose of phenytoin and pentobarbital solution. This was followed by a 2 minute perfusion in heparinized 0.9% saline immediately followed by perfusion of 200 mls of freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.5). Brains were removed 1-4 hours later and immersion fixed for a further 24 hours before being transferred to cryo-preservant (10% glycerol in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.5). Brains were sectioned frontally at 40 μm and stored in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.05% azide at 4°C. Striatal sections at the level of the anterior commissure were incubated with primary anti-huntingtin antibody EM48 (Chemicon) at 1:1000 dilution in PBS-0.1% tween-10% goat serum for 3 days at 4C, then followed by a 24 hour incubation with Alexa-fluor 488 labeled secondary antibody at 1:500 dilution (Life Technologies). Sections were washed in PBS three times for 10 minutes and stained with fluorescent Nissl (Life Technologies) for 1 hour at room temperature (1:100 dilution in PBS), followed by washing in PBS twice for 15 minutes and mounting on slides using Fluoromount G (Southern Biotech). Slides were air-dried overnight in the dark and then stored at 4C. Nissl stain was used to detect neuronal cell bodies at 640/660 nm. Images were captured using a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope. We stained several striatal sections per mouse to identify sections containing expressed protein. Within each region of positive mHTT staining 2-3 image stacks were obtained using a 60x objective (z-stack interval = 0.46 µm). Within these images we quantified all striatal neurons regardless of whether there was mHTT staining as suppression of mHTT levels by TRX1 or TMX3 could result in loss of detectable staining. Striatal neuronal volumes were estimated using the confocal module in Stereoinvestigator software (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT) and the five-ray nucleator method.

Quantitative PCR for TMX3 and TXN1 in N171-82Q HD mice: We used essentially the same method as previously described35.

Statistical analyses: Data was analyzed with SAS software version 9. Student’s t-test were used for the analysis of the secondary screens. One-way ANOVA was used for the analysis striatal neuronal volumes. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze spontaneous wheel-running data. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Identification of TRX1 and TMX3 as candidate mHTT decreasing proteins in HD

We studied a broad range of human thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase genes. This group includes all the well-studied thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases to include the glutaredoxin, thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase gene families. There are a growing number of poorly characterized proteins considered to have a thioredoxin-like domain and probable thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase activity. We studied several of these proteins to include the thioredoxin-related transmembrane proteins and thioredoxin-like proteins. COS1 cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding the N171-40Q fragment of mHTT protein together with a plasmid encoding the test thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase. Co-transfection with plasmids encoding N171-40Q mHTT and GFP were used as controls. Cells were lysed 24 hours post-transfection and analyzed for soluble mHTT levels. For each gene studied, N171-40Q expression was normalized to actin then the result normalized to the N171-40Q/GFP control (100%). As shown in Fig. 1A, we found markedly different effects of test thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases on soluble N171-40Q mHTT levels. However, we subsequently found that co-transfection with GFP significantly suppressed N171-40Q protein levels (not shown). Therefore, rather than comparing test genes with the N171-40Q/GFP baseline, we qualitatively selected genes for more detailed testing based on them resulting in low or high N171-40Q expression levels, compared to other candidates. Thioredoxin 1 (TRX1) and thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 3 (TMX3) were chosen as candidates that may decrease N171-40Q levels. Glutaredoxin 1 (GLX1), protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 6 (PDIA6) and FLJ44606 were chosen as candidates that may increase mHTT. Sel-M and Sel-15 are selenoproteins that were also mHTT decreasing candidates; they were not included in subsequent investigations. To provide a more rigorous assessment of the selected candidates we developed a secondary screening assay to further validate results. The candidate proteins share a common thioredoxin-domain structure with the same catalytic mechanism that involves a C-X-X-C motif. Further, mutation of the first cysteine residue of this site blocks enzymatic activity32. To specifically assess the effect of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase enzymatic activity on mHTT levels in our secondary screen we compared the effect of active protein with protein in which enzymatic activity had been blocked by replacement of the critical cysteine with serine (see methods). As shown in Fig. 1B-D GLX1 (1B) increased mHTT (p<0.05); TRX1 (1C) decreased mHTT (p<0.05); and TMX3 (1D) decreased mHTT (p<0.01) consistent with the findings from the primary screen (Fig. 1A). However, active LJ44606 (1E) and PDIA6 (1F) had no effect on mHTT levels (p>0.05). GLX1 increased N171-40Q protein levels (1B) suggesting that GLX1 inhibitors may decrease mHTT. However, while GLX1 knockout is not lethal in mice36 the protein is required for normal mitochondrial function26. As GLX1 inhibitors would be predicted to be toxic, we excluded it from further investigation.

To further elucidate mechanisms for decreasing mHTT levels in cells we used two approaches. First, we tested to determine if TRX1 and TMX3 can decrease levels of a N171-40Q variant that lacks thiol-containing cysteine residues and does not form reduction-sensitive oligomers. We used a plasmid encoding N171-40Q-4CA in which all four cysteine residues are mutated to block formation of thiol-dependent oligomers6. In co-transfection experiments there was no effect of TRX1 and TMX3 on decreasing N171-40Q-4CA as compared to mutant TRX1 and mutant TMX3 controls (Fig. 2A-B). Infact, functional TMX3 increased N171-40Q-4CA compared to mutant TMX3 control (p<0.05) (Fig. 2B). The reason for this is unclear. However, the lack of decrease of N171-40Q-4CA by active TXN1 and TMX3 suggests that the decreasing effects of these thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase on N171-40Q levels depends on the presence of N171 HTT thiols. TRX1 is a cytosolic and nuclear protein and could therefore have direct contact with HTT37,38. We therefore addressed if N171-40Q mHTT is a direct substrate of TRX1. We used a previously described method that can trap TRX1 with its substrate in a catalytic intermediate state [34] . As shown in Fig. 3 we found no evidence that N171-40Q mHTT is a direct substrate of TRX1 under cell-free conditions. Similar experiments using transfected COS cells also failed to find evidence of a direct interaction between N171 HTT and TRX1 (not shown). TMX3 is a transmembrane protein with its active site within the endoplasmic reticulum39. As there is no evidence that HTT is an endoplasmic reticulum luminal protein we did not test for a direct TMX3 HTT interaction. However, as both TRX1 and TMX3 could be protective by effects on non-HTT targets we tested them in mouse HD.

Validation of a lentiviral mouse model of HD

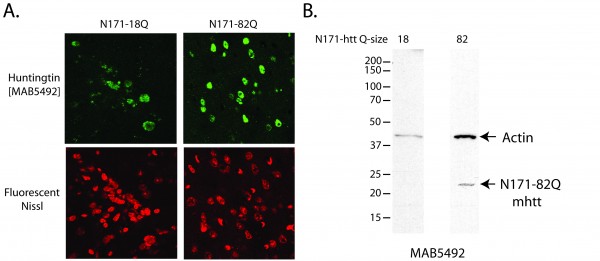

Lentiviral vectors have been used to model HD in rats and macaques40. We used a four plasmid lentiviral system previously described by de Almeida et al in rats31 to model HD in wild-type mice. This system drives expression of the N171 HTT fragment under the control of the phosphoglycerate kinase promoter providing neuronal expression at physiologically relevant protein levels. Mice were injected with virus at ~8 weeks and sacrificed as ~14 weeks of age. Lentiviral-mediated expression of N171-18Q and 82Q HTT resulted in detectable expression by immunofluorescence staining of brain sections (Fig. 4A). However, neuronal expression was only found immediately around the needle tract. Western blot analysis failed to detect N171-18Q but detected N171-82Q (Fig. 4B). Therefore, both wild-type and mutant N171 protein were expressed in brain; higher expression of mHTT may be related to its accumulation as part of the disease process41. We chose to use striatal neuronal cell body volume as our main outcome as cell atrophy is a consistent manifestation of mHTT expression in neurons42. In this preliminary study, while differences were not statistically significant (p=0.2202) striatal neuronal cell body volume means were lower in the N171-82Q (n=11) versus N171-18Q (n=5) group (520 ± 53 and 639 ± 78 µm3, respectively).

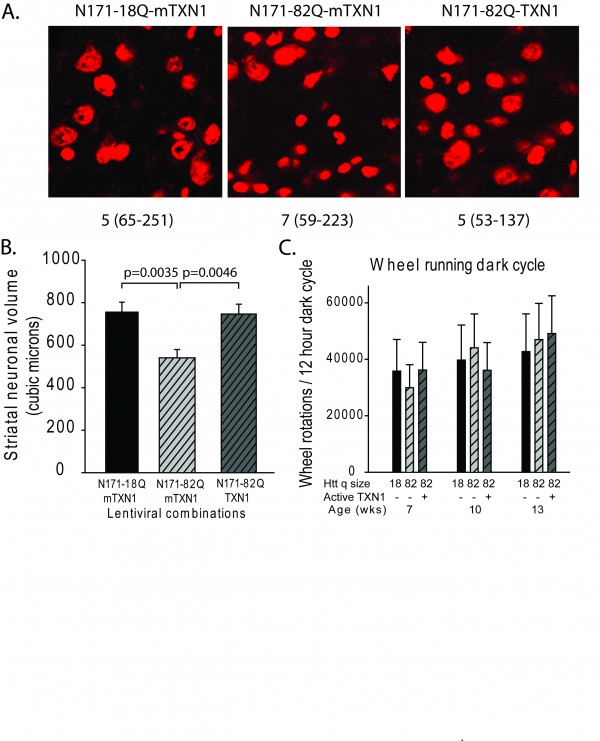

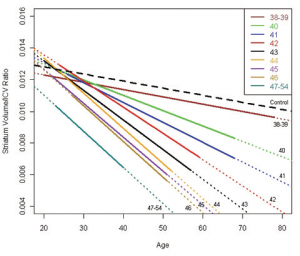

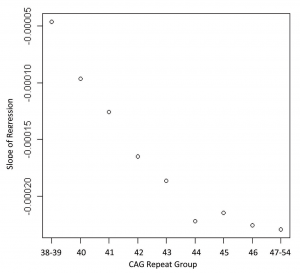

TRX1 and TMX3 decrease neuronal atrophy in mouse HD

We sub-cloned cDNA-encoding TMX3 and TRX1 into the same lentiviral expression system used for N171 expression31 then generated enzymatically inactive variants by point mutagenesis for use as gene-specific controls for enzymatic activity of the test protein. We removed the histidine tags during the sub-cloning process. While we did not attempt to show protein expression in brain, we did demonstrate in-vivo transcript expression of TMX3 and TRX1 in liver 6 weeks after intra-venous injection of neonatal mice (not shown). We then undertook experiments in which we compared the effects of N171-18Q, N171-82Q, and N171-82Q with TMX3 or TRX1 following mouse striatal injection. To control for the total level of lentiviral delivery to striatum we co-injected virus encoding mutant (inactive) TMX3 or TRX1 in the N171-18Q and N171-82Q treatment groups. Striatal injections were at ~8 weeks and mice were sacrificed at ~14 weeks of age. We completed confocal stereology to quantify striatal neuronal cell body volume. As our candidate treatments were chosen based on their ability to decrease mHTT it is possible that mHTT would not be detected in an infected cell by immunofluorescence and that the transduced cell would not be quantified. Therefore, we changed our methodologic approach. We stained brain sections for mHTT then captured confocal images in regions where there was some neuronal mHTT staining. We then quantified cell body volume for all neurons within an image stack. As shown in Fig. 5 (TMX3 experiment) and Fig. 6 (TRX1 experiment) we found that striatal neuronal cell body volumes were significantly decreased in N171-82Q versus N171-18Q expressing mice (p-values: 0.0350 and 0.0035, respectively). Functionally active TMX3 and TRX1 both decreased this effect of mHTT on striatal neuronal atrophy (p-values: 0.0387 and 0.0046, respectively). Due to the presence of detectable mHTT staining only around the needle tract quantification of soluble mHTT levels by Western blot analysis following brain dissection would not have been reliable therefore we did not attempt this. Finally, we studied TRX1 and TMX3 transcript levels by qPCR in 14-week old N171-82Q transgenic HD mice (equivalent to early-advanced disease35); these mice express the N171-82Q HTT fragment under the control of the prion promoter8 (Fig. 7). There was no evidence of decreased expression of both genes in striatum and cerebral cortex; in fact, in striatal TRX1 transcript expression was significantly increased in HD mice (p<0.01) (Fig. 7A). We additionally completed searches of publically available HD micro-array data sets using GeoProfiles. In the R6/1 mouse model of HD there was an increase in cerebral TXN1 transcript from 22-27 weeks of age with 1 of 2 probes; TMX3 transcript changes were not found43. Micro-array analysis in 12 and 24 month old full-length mHTT expressing YAC128 HD and wild-type litter-mate striata did not reveal expression differences for TXN1 or TMX344.

Discussion

Abnormal redox homeostasis and oxidative stress are consistent features of human HD and cell-based and animal models45,46. Identification of appropriate targets for modulation of redox homeostasis could provide novel therapeutic approaches for treating HD. Protein thiols are an important site of post-translational modification involved in the regulation of redox responsive cell signaling processes24. Oxidative stress can result in increased protein thiol oxidation and disruption of these homeostatic processes, potentially contributing to cell dysfunction and degeneration. Transgenic mice expressing the N171 mHTT protein fragment develop a phenotype similar to human HD including striatal atrophy47. We have shown that the N171 fragment of HTT can form thiol-dependent oligomers which are degraded more slowly than a N171 protein variant that lacks thiols and is unable to oligomerize6. Numerous proteins with thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase activity exist that facilitate the reduction of oxidized protein thiols in cells24. Here we sought to identify if there are thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase enzymes that can decrease mHTT levels in cells and provide protection against neuronal atrophy in HD mice. We tested a representative set of thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases for mHTT decreasing effects. We used primary and secondary cell-based screens to identify candidate genes for testing in HD mice (Fig. 1). Based on our previous findings6 enzymatic conversion of mHTT oligomer to monomer by a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase is expected to result in increased monomer degradation and potentially no change in monomer to oligomer ratio; we therefore quantified total soluble mHTT levels by reducing SDS-PAGE in our cell-based studies. To enable timely progression to in-vivo testing we utilized a lentiviral system to drive expression of N171 mHTT and test our candidate genes in mouse brain (Figs. 5-6).

Consistent with reports of lentivirus-induced HD in rats showing no behavioral changes31, effects of striatal expression of N171-82Q mHTT in mice on spontaneous wheel running activity were not found (Figs. 5-6). N171 HTT expression was found mainly around the needle tract suggesting transduction of a small percentage of the overall striatal volume potentially explaining the lack of a behavioral phenotype. However, by characterizing somal volume of neurons we were able to obtain a measure of the effect of mHTT and test proteins TRX1 and TMX3. Neuronal atrophy is a consistent morphologic feature of HD and is frequently used as a marker of therapeutic effect 42. Based on this outcome, we provide evidence that both TRX1 and TMX3 have protective effects in the lentiviral mouse HD system tested (Figs. 5-6).

TRX1 is a well-characterized cytoplasmic and nuclear thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase that has previously been demonstrated to have protective effects in models of acute and chronic neurodegeneration. TRX1 transgenic mice demonstrate increased resistance to neuronal degeneration induced by transient focal ischemia48. TRX1 interacting protein (TXNIP) is an endogenous inhibitor of TRX1 and is expressed in brain49. Furthermore, TXNIP inhibitors provide protection in a rodent model of thromboembolic stroke50. TRX1 has also been shown to promote neurogenesis and cognitive recovery following cerebral ischemia in mice51. DJ-1 is an anti-oxidant protein; mutations in DJ-1 cause autosomal recessive early-onset Parkinson’s disease52. In one study, it was shown that DJ-1 mediates its neuroprotective effects by stimulating Nrf2-mediated upregulation of TRX153. The protective effect of 17β-estradiol in the tumor necrosis factor model of optic neuropathy is also mediated by TRX154. Protective effects of TRX1 in disparate models of neuronal degeneration are consistent with its key role in redox regulation of signaling pathways and repair of oxidatively-modified thiols within diverse proteins. The current findings demonstrate that protective effects of TRX1 also extend to a model of mouse HD.

To determine if the effect of TRX1 on decreasing N171 mHTT (Fig. 1) is the result of a direct effect of TRX1 on N171-40Q we used a previously reported approach that utilizes a TRX1 variant to trap the intermediate catalytic state of TRX1 di-sulfide linked to its substrate protein as a heterodimer34. We used purified N171-40Q HTT and TRX1 or mutant TRX1 in a cell-free assay to maximize the chances of finding an interaction. Despite this, we found no evidence that N171-40Q HTT is a direct substrate of TRX1 (Fig. 3). As this result could be because the proteins expressed in bacteria failed to fold properly, we undertook similar experiments in transfected COS cells but also failed to find evidence for a disulfide-linked heterodimer species (not shown). Therefore, while we cannot fully exclude the possibility, we have no data to indicate that N171 HTT disulfides55 may be a direct substrate of TXN1.

TRX1 has many substrate proteins23,56. Therefore, the neuronal atrophy decreasing effect of TRX1 that we observed (Fig. 6) may be the result of effects on non-HTT targets. Peroxiredoxins are a family of redox proteins that regulate hydrogen and lipid peroxide levels by oxidation of catalytic cysteine thiols then subsequent reductive re-activation. Thioredoxins activate oxidized peroxiredoxins57. Importantly, it has been shown in a rat cell model of HD that there is increased thiol oxidization of peroxiredoxins 1, 2 and 4 implying a functionally inactive state. Further, treatment of this cell line with a dithiol compound protected against mHTT-induced toxicity and decreased the level of peroxiredoxin 1 oxidation17. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK1) is a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase and an important regulator of oxidative and ER stress-induced apoptosis58. Inhibition of ASK1 using intra-cerebral infusion of an antibody has protective effects in mouse HD, decreasing ER stress and resulting in behavioral improvements59. TRX1 is a negative regulator of ASK160; therefore, this is another potential mechanism of protection in our model. Therefore, while a weakness of this study is that the mechanism of protection by TRX1 in our HD mouse model is undetermined, there are several substrate proteins that are in HD-associated pathways and that could be mediating protective effects.

TMX3, in contrast to TRX1, has not previously been linked to neuroprotection for any brain disorder. However, mutations in the TMX3 gene have been linked with microphthalmia and retinal developmental anomalies61. TMX3 is a single domain transmembrane protein. It is primarily located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), with its catalytic domain in the ER lumen62 but is also present in the mitochondrial-associated membrane63. Protein substrates of TMX3 have not been reported. Huntingtin protein is associated with ER membranes and has a role in intra-cellular trafficking between the Golgi and extracellular space64; however, it has not been shown to be present within the ER lumen. As the TMX3 catalytic domain and N171-40Q mHTT would not be expected to be present within the same cell compartment it is improbable that the N171 fragment is a direct substrate of TMX3. However, mHTT expression does induce ER stress65. Increased expression of TMX3 in striatum may protect against mHTT-induced ER pathology.

In summary, we have identified TRX1 and TMX3 as proteins that decrease both mHTT levels in cultured cells and mHTT-induced striatal neuronal atrophy in HD mice. These findings support a role of thiol stress in the pathogenesis of HD. While the findings of this study are novel there are some limitations. First, lentiviral protein expression in brain was only found surrounding the needle tract with less spread than has been reported previously in rats31. While the findings from the morphometric analysis of neuronal cell-body size indicate protective effects, selection bias in sampling offsets the strengths of the stereologic method used. Second, while neuronal atrophy is an important feature of HD neurodegeneration42 this was the only outcome for which we found an effect of mHTT expression in our lentiviral model. Despite the weaknesses, the findings suggest that specific modulation of thiol homeostasis has beneficial effects in HD models. Future studies could address if increased expression of TRX1 and TMX3 globally in mouse HD brain provides protection against multiple measures of neurodegeneration.

COS1 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding human thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase proteins and N171-40Q mutant huntingtin protein (mhtt). Twenty-four hours later cells were lysed and analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis to quantify total soluble N171 mhtt. N171-40Q mutant huntingtin levels (MAB5492 – Millipore) were normalized to actin then to co-transfection control. TRX1 and TMX3 were chosen as targets that may decrease mhtt levels; glutaredoxin 1 (GLX1), PDIA6 and FLJ44606 were chosen as targets that may increase mhtt. See results for more details. Shown are mean ± SEM. n=3, B-F. Secondary screen. COS1 cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding N171-40Q and wild-type or enzymatically non-functional (control) human thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases. Twenty-four hours later cells were lysed for reducing SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis. Candidate gene expression was confirmed by PCR. The letter/number codes above the right western blot lanes are the substitution of the mutant inactive protein. n=3-5, B. Glutaredoxin 1 (GLX1) increases soluble N171-40Q mhtt levels. n=5, C. Thioredoxin 1 (TRX1) decreases soluble N171-40Q mhtt levels. n=5, D. TMX3 decreases soluble N171-40Q mhtt levels. n=4, E. FLJ44606 has no effect on N171-40Q mhtt levels. n=4, F. Protein disulfide isomerase A6 (PDIA6) has no effect on N171-40Q mhtt levels. n=5. P-values: *<0.05 and **<0.01.

Fig. 1: Primary and secondary screens for thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases that change total soluble mutant huntingtin protein levels

A-B. COS1 cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding mhtt with cysteines mutated to alanines (N171-40Q-4CA) and TRX1 / TMX3. The letter/number codes above the right western blot lanes are the substitution of the mutant inactive protein. A. TRX1 does not decrease soluble N171-40Q-4CA levels. B. TMX3 increases N171-40Q-4CA levels. n=4. P-values: *<0.05.

Fig. 2: TRX1 and TMX3 do not decrease levels of thiol-blocked N171-40Q mutant huntingtin

TRX1, mutant TRX1 (C35S) and N171-40Q were expressed and purified from bacteria. N171-40Q was incubated with TRX1 or mTRX1 at 250 C for 1 hour then free thiols blocked with 50 mM N-ethylmaleimide. Samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE (see methods). Lanes: 1=N171-40Q htt alone; 2=TRX1 alone; 3=mTRX1 alone; 4-5=N171-40Q and TRX1; and 6-7= N171-40Q and mTRX1. Mutant TRX1 (C35S) is predicted to trap substrate proteins as heterodimers [33]. There is no evidence of a heterodimer band (estimated mass = 46 kDa) in the non-reduced N171-40Q and mTRX1 group (lane 6). The band migrating at ~65 kDa (most prominent in lanes 4 and 6) is dimeric N171-40Q as previously reported6.

Fig. 3: TRX1 does not interact directly with N171-40Q mutant huntingtin in a cell-free assay

A-B. Lentivirus encoding N171 htt fragments was injected intra-striatally into 8-week-old mice; sacrifice was at 14-weeks of age. A. Detection of N171 htt in mouse striata following stereotaxic injection. Brains sections at the level of the stereotaxic injections were stained for N171 htt using MAB5492 (Chemicon) and with a fluorescent Nissl staining. Top left shows detection of 171-18Q; top right shows detection of N171-82Q; bottom show fluorescent Nissl staining. B. Detection of htt expression by Western blot analysis. Striata were dissected then homogenized to extract protein for Western blot analysis using MAB5492. N171-18Q is not detected. N171-82Q is detected.

Fig. 4: Characterization of huntingtin expression in mouse brain following lentiviral delivery

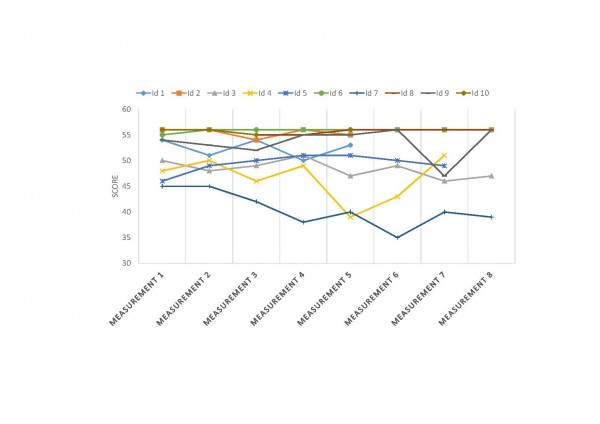

A-B. Mice were injected with lentiviral combinations (methods) at 8-weeks of age and sacrificed at 14-weeks. Brain sections were stained for Nissl substance and mhtt. Confocal images were collected in the region where htt staining was detected. Neuronal cell body volumes were determined using the nucleator method on confocal z-stack images (methods). A. Representative images of fluorescent Nissl stained neurons in the region of the striatal injection site. Numbers below images represent the number of mice per treatment group; numbers in parenthesis represent the minimum and maximum number of neurons counted per mouse within the group. B. Striatal neuronal cell body volume. Mice expressing N171-82Q and mutant (inactive) TMX3 (mTMX3) have significantly smaller neuronal cell bodies than mice expressing N171-82Q and active TMX3. The main effect p-value is 0.0346; pair-wise comparison p-values are on graph. n=9-10. C. Spontaneous wheel running activity is not altered by N171-18/82Q and / or TMX3 expression. See methods for experimental details. n=10.

Fig. 5: TMX3 expression decreases striatal neuronal atrophy in HD mice

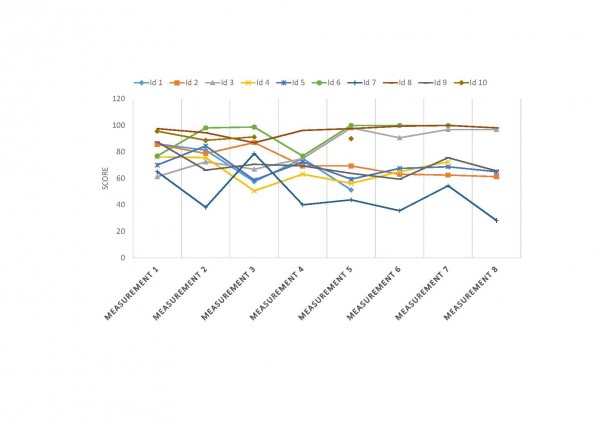

A-B. Experimental design was as described for figure 5. A. Representative images of fluorescent Nissl stained neurons in the region of the striatal injection site. Numbers below images represent the number of mice per treatment group; numbers in parenthesis represent the minimum and maximum number of neurons counted per mouse within the group. B. Striatal neuronal cell body volume. Mice expressing N171-82Q and mutant (inactive) TRX1 (mTRX1) have significantly smaller neuronal cell bodies than mice expressing N171-82Q and active TRX1. The main effect p-value is 0.0545; pair-wise comparison p-values are on graph. n=5-7, C. Spontaneous wheel running activity is not altered by N171-18/82Q and / or TXN1 expression. See methods for experimental details. n=7-9.

Fig. 6: TRX1 expression decreases striatal neuronal atrophy in HD mice

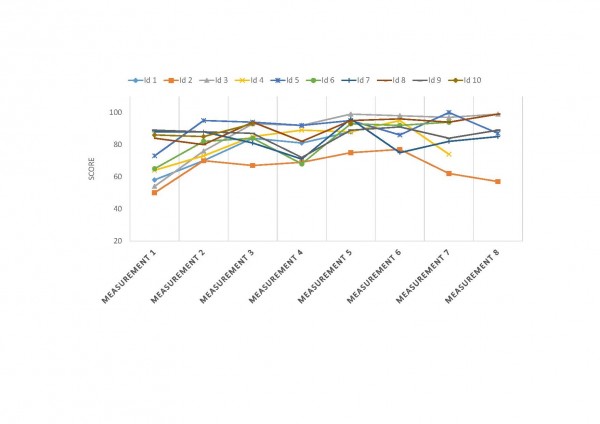

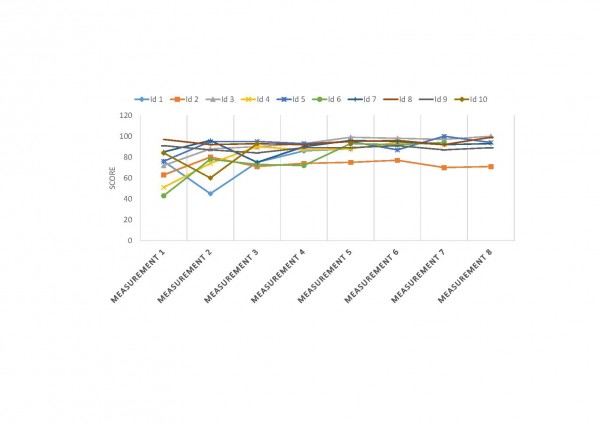

A. Transcript-encoding TRX1 in HD mice is significant higher than WT littermates in striatum, but not cortex. B. Transcript-encoding TMX3 in HD mice is not altered compared to WT littermates in striatum and cortex. All analyses were in 14-week-old mice corresponding to early-advanced disease. Values are normalized to actin. Shown are means ± 95% confidence interval. n=9-10, p=value: **<0.01.

Fig. 7: TRX1 and TMX3 transcript levels in transgenic N171-82Q HD mouse brain

List of abbreviations

Mutant huntingtin protein, mhtt; Huntington’s disease, HD; endoplasmic reticulum, ER; sodium dodecyl sulfate, SDS; thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 3, TMX3; thioredoxin 1, TRX1; protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 6, PDIA6.

Competing interest statement

I have read the journal’s policy and have the following conflict. Application serial number 13/854,809 filed with US patent office.

Author contributions

ZL carried out cell culture studies, synthesized plasmid constructs, and assisted with the mouse experiments and writing of the paper. LB carried out the viral synthesis and mouse experiments. JF conceived, designed and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Introduction

Huntington disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant, neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expanded trinucleotide (CAG) repeat sequence in the first exon of the HD (HTT) gene, leading to an enlarged polyglutamine tract in the encoded protein huntingtin.1 Unwanted choreiform movements, psychiatric and behavioural disturbances and cognitive impairment characterize the disease. Other less well-known, but debilitating manifestations of HD include weight loss, sleep disturbances and autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction.2 Unfortunately, there are no disease-modifying therapies available, although a number of potential disease-modifying drugs are currently in development.2 In order to rapidly assess these drugs in clinical trials there is a pressing need for reliable biomarkers with a high sensitivity to disease progression.3 As HD is a slowly progressive disease such biomarkers could initially be applied as surrogate trial end-points to allow rapid prioritization of potentially effective drugs. Subsequently, promising candidate drugs could be tested further for clinical efficacy in randomized trials using suitable clinical end-points.3

Recently a substantial depletion of cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), the principal enzyme involved in the generation of cysteine from cystathionine, was shown in HD.4,5 The levels of this enzyme were profoundly decreased in HD striatal cell lines containing 111 glutamine residues, in brains of two transgenic HD mouse models (i.e. R6/2 and Q175 mice) as well as in post-mortem brain samples of HD patients.4 Importantly, the levels of CSE in liver and pancreatic lysates of R6/2 mice were decreased to a similar extent as those in the brain, purportedly due to an aberrant interaction of the mutant huntingtin protein with specificity protein-1, a transcriptional activator of CSE.4 Paralleling findings in individuals with inactivating mutations of the cystathionine γ-lyase (CTH) gene which encodes CSE, a depletion of CSE might result in elevated levels of cystathionine in both blood and urine.6 Therefore, we hypothesized that the levels of cystathionine in both blood and urine may be increased in patients with HD compared to matched controls and that this increase might correlate with disease progression.

Methods

Clinical protocol

We used data and plasma/urine samples collected in our earlier studies, the protocols of which have been described previously.7,8 In brief, nine early-stage HD patients and nine healthy control subjects, matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI), were enrolled.7,8 In the patient group, mutant CAG repeat size ranged between 41 and 50. The clinical diagnosis of HD was made by a neurologist specialized in movement disorders (R.A.C.R.). The Unified Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) was used to assess HD symptoms and signs. All subjects were free of medication. Subjects were eligible for participation after exclusion of hypertension, any known (history of) pituitary disease, recent intentional weight change (>3 kg weight gain or loss within the last 3 months), and any other chronic conditions except HD. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Leiden University Medical Centre. Subjects were admitted to the Clinical Research Center for blood sampling. A cannula was inserted into an antecubital vein and 2-3 mL blood samples were collected with S-monovetten (Sarstedt, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands). Sampling started at 16:30 and continued for 24 hours at 10-min intervals. EDTA tubes were put immediately on ice and centrifuged within an hour at 1610 g at 4 ºC for 20 min, and plasma was stored at -80 ºC. Three standardized meals were served at 09:00, 13:00, and 19:00 h (Nutridrink, 1.5 kcal/ml, 1500–1800 kcal/d; macronutrient composition per 100 ml: protein, 5 g; fat, 6.5 g; carbohydrate, 17.9 g; Nutricia, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands). Subjects remained sedentary except for bathroom visits. Furthermore, twenty-four hour urine was collected and stored at -80 ºC. No daytime naps were allowed. Lights were switched off at 23:00 h and, the next morning, subjects were awakened at 07:30 h. Bioelectrical impedance analysis was used to assess lean body mass and fat percentage at 08:00 h.

Assays

Concentrations of cystathionine as well as 22 other amino acids (alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartic acid, citrulline, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, ornithine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, taurine, threonine, tryptophan, tyrosine and valine) were determined in fasting plasma samples obtained at 08:30 h and samples from 24-hour urine. Additionally, cystine levels were determined in urine samples only as the levels of this amino acid could not be reliably quantified in stored plasma samples. All samples were analysed once according to a procedure described before9 with minor modifications, on a Biochrom 30 automated amino acid analyser (Biochrom, Cambridge, UK) using standard conditions for physiological amino acid separation. The minor modifications were: 250 µL of plasma (and urine) were used instead of 400 µL, 40 µL of the plasma supernatant (and 20 µL of the urine supernatant) was injected instead of 60 µL and a 13 mm membrane filter was used instead of a 25 mm membrane filter. The detection limits of the assays were 1 μmol/L for plasma and 1 μmol/mmol creatinine for urine and total analysis time was 173 min.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as medians and interquartile ranges unless otherwise specified. Because of small group sizes the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was applied to assess intergroup differences, while Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to assess all correlations. All tests were two-tailed and significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Subjects

The HD and the control group did not differ with respect to age, sex, body mass index, body fat or lean body mass (all p ≥ 0.27 , Table 1).

Characteristics of the study population

HD patients*

Controls*

p-value

Male/female

6/3

6/3

–

Age [y]

47.1 (3.4)

48.6 (3.3)

0.691

BMI

24.1 (1.0)

24.3 (0.6)

0.691

Fat [%]

25.5 (2.4)

25.6 (2.4)

0.825

Lean body mass [kg]

57.3 (3.2)

56.2 (3.0)

0.691

Waist-to-hip ratio

0.89 (0.03)

0.94 (0.02)

0.270

Mutant CAG repeat size

44.4 (1.0)

–

–

Age of onset [y]

41.4 (3.0)

–

–

Disease duration [y]

5.7 (1.1)

–

–

UHDRS motor score

22.2 (6.0)

–

–

TFC score

11.7 (0.7)

–

–

*) Values are indicated as mean (SE).

Abbreviations: BMI = Body Mass Index; TFC = Total Functional Capacity; UHDRS = Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale.

Amino acid concentrations

There were no significant differences in plasma or urine concentrations of cystathionine between HD patients and controls (all p ≥ 0.102, Table 2). Neither did the levels of the other amino acids differ between HD patients and controls (all p ≥ 0.102, Table 2).

Amino acid concentrations

Plasmaa

Urineb

HD patients

Controls

HD patients

Controls

Alanine

256 (235-393)

288 (236-444)

37.0 (21.5-43.2)

28.5 (27.6-39.1)

Arginine

99 (69-107)

102 (71-109)

2.2 (1.5-2.7)

2.0 (1.7-2.9)

Asparagine

42 (34-51)

52 (37-58)

13.6 (8.8-23.2)

14.8 (10.7-16.0)

Aspartic acid

9 (8-13)

11 (11-13)

12.6 (11.3-14.2)

11.6 (10.7-12.5)

Citrulline

38 (32-47)

42 (39-45)

0.5 (0.5-2.0)c

0.5 (0.5-0.8)c

Cystathionine

2 (2-3)

2 (2-3)

2.3 (0.9-2.7)c

1.1 (0.5-2.5)c

Cystine

–

–

7.1 (5.8-9.7)

5.6 (4.8-6.5)

Glutamine

626 (530-685)

611 (550-692)

59.3 (35.9-84.0)

45.3 (43.0-57.8)

Glutamic acid

40 (32-67)

40 (34-52)

2.9 (2.3-4.0)

2.7 (2.0-3.3)

Glycine

223 (158-282)

256 (209-307)

129.1 (105.2-286.0)

136.1 (118.5-197.7)

Histidine

75 (63-92)

82 (74-88)

78.1 (46.6-139.7)

79.3 (59.0-94.7)

Isoleucine

60 (53-80)

68 (57-82)

1.5 (0.5-1.7)c

1.1 (0.5-1.6)c

Leucine

133 (104-149)

140 (101-164)

2.9 (2.0-4.1)

3.0 (2.2-3.4)

Lysine

183 (141-218)

187 (176-213)

24.6 (20.9-49.0)

23.4 (20.6-30.9)

Methionine

24 (20-32)

24 (22-34)

2.3 (1.7-2.5)

1.8 (1.4-2.4)

Ornithine

47 (42-58)

47 (39-59)

2.6 (1.3-3.1)

3.0 (1.7-3.9)

Phenylalanine

62 (51-76)

61 (53-73)

6.8 (5.3-8.7)

5.6 (4.1-6.7)

Proline

191 (154-247)

190 (168-264)

ND

ND

Serine

105 (77-125)

111 (107-122)

43.8 (24.0-65.0)

41.4 (35.9-44.6)

Taurine

33 (29-43)

34 (32-43)

84.2 (33.5-100.7)

64.3 (22.9-95.9)

Threonine

113 (95-161)

123 (113-146)

19.1 (10.9-25.6)

15.9 (11.2-18.1)

Tryptophan

59 (36-72)

56 (50-67)

ND

ND

Tyrosine

55 (42-64)

55 (49-66)

10.1 (7.3-16.8)

9.8(6.6-12.1)

Valine

246 (202-257)

247 (203-261)

4.4 (3.2-6.9)

3.9 (3.3-5.0)

Results are presented as medians (interquartile range). ND: not detectable. There were no significant intergroup differences for any amino acid either in plasma or in urine (all p ≥ 0.102).

a) Plasma concentrations are in μmol/L.

b) Urine concentrations are in μmol/mmol creatinine.

c) In some participants amino acid concentrations were below the limit of detection of the assay. In order to calculate summary measures, the expected amino acid concentrations in these subjects were assumed to be half of the detection limit.

Association with clinical features

In HD patients plasma cystathionine levels did not correlate with any UHDRS domain score (all p ≥ 0.33). Conversely, urine cystathionine levels were significantly correlated with the total functional capacity score (r = -0.75, p = 0.020), but not with total motor score (r = +0.44, p = 0.242). Urine cystine levels were associated with both total motor score (r = +0.67, p = 0.050) and total functional capacity score (r = -0.71, p = 0.032). There were no significant associations between cystathionine levels in either plasma or urine and total behavioural score, CAG repeat size or body mass index (all p ≥ 0.71). Of the other amino acids studied urine levels of arginine, aspartic acid, citrulline, isoleucine, leucine and taurine were significantly associated with either total motor score or total functional capacity score (all p < 0.050). Plasma levels of none of these and other amino acids were associated with either total motor score or total functional capacity (all p ≥ 0.092).

Discussion

As recently reported45, a major decrease of CSE, which is the main generator of cysteine from cystathionine, would be expected to result in increased levels of cystathionine in HD patients. However, in this pilot study we found similar concentrations of cystathionine in both fasting plasma samples and samples from 24-hours urine in early-stage HD patients and matched controls. There are several likely explanations for this apparent discrepancy. First, although Paul et. al demonstrated significantly decreased levels of CSE in brains of HD patients, they did not study levels of CSE in peripheral tissues of these patients. Moreover, the depletion of CSE levels in hepatic and pancreatic tissue of R6/2 mice was less pronounced than in their brain tissue.4 Therefore, it could be that CSE depletion only leads to detectable changes in cystathionine levels in brain and/or cerebrospinal fluid, but not peripheral tissues, of HD patients. Second, the post-mortem patient material studied by Paul et al. likely originated from end-stage HD patients, whereas we studied early-stage patients. Thus, given the significant associations between cystathionine levels and disease severity in our small group of patients, it is conceivable that in more advanced HD patients levels of cystathionine will indeed become abnormal.

We neither found any evidence for decreased levels of other amino acids including alanine or the branched chain amino acids isoleucine, leucine and valine in HD patients as reported earlier.11,12,13 We did find an association between urine levels of, among others, isoleucine and leucine and disease severity in our group of early-stage HD patients suggesting that the levels of some amino acids might become abnormal with disease progression, although these associations should be interpreted cautiously given the low amino acid concentrations. Another possible explanation for the lack of differences in amino acid levels between our patient and control group could be that in contrast to previous studies we also accounted for dietary intake by providing the same standardized meals to all participants thereby decreasing confounding effects mediated through differences in dietary composition.10 However, in any case our study does not suggest large changes in any amino acid in early-stage HD patients.

In conclusion, we found no evidence for changes in plasma or urine concentrations of cystathionine or any other amino acid in early-stage HD patients. Although we found associations between cystathionine, as well as several other amino acids, and disease severity, the potential of these amino acids to serve as state biomarkers in HD needs further validation in larger groups of patients.

Competing Interest statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

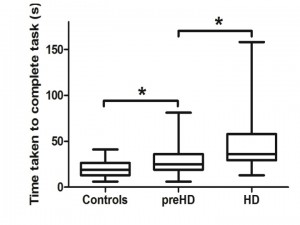

Methods: Premanifest HD (n=24), manifest HD (n=27) and control (n=32) participants were asked to screw a nut onto a bolt in one direction, using three different sized bolts with their left and right hand in turn.

Results: We identified some impairments at all stages of HD and in the premanifest individuals, deficits in the non-dominant hand correlated with disease burden scores.

Conclusion: This simple, cheap motor task was able to detect motor impairments in both premanifest and manifest HD and as such might be a useful quantifiable measure of motor function for use in clinical studies.

]]>INTRODUCTION

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant condition causing neurodegeneration of the cortex1 white matter2,3 and basal ganglia4,5. This leads clinically to motor deficits including chorea, bradykinesia, and dystonia as well as cognitive deficits, circadian rhythm disturbances and psychiatric problems6,7. The ability to robustly detect early motor impairments in HD using a simple cheap test is needed to provide an objective quantifiable measure of motor performance that is useful both clinically and as an endpoint in therapeutic trials, and which can be followed over time. Also more tests that measure everyday motor tasks that impact on functional independence as the disease progresses are required. As such, many groups, including our own, have sought to develop motor tasks to detect and track early changes in premanifest HD (preHD)8,9 including both the finger8,9 and hand tapping tests 10,11,12,13 Motor differences are not just seen in tapping tasks, as other studies have shown that there are changes in the variability of grip force in a grasping task in HD patients 14; a reduction in tongue force in preHD patients 15; a reduction of speech rate in motor speech tasks 16 and impairments in saccade latency and velocity in HD 12,17. Furthermore these simple tasks have been correlated to structural brain changes in HD and preHD 18 as well as cognitive deficits 19. Other more complex motor tasks such as those involving diadochokinetic movements 20 and peg insertions, whilst able to detect impairments in manifest disease are insensitive during preHD 21. Many of these tasks described require specialized equipment and complicated analysis. In this paper we have assessed participants with manifest HD and preHD using a very simple and cheap nut and bolt test which has previously been used to look at the effects of extravehicular activity (EVA) gloves on dexterity, grip force and coordination in healthy participants 22. This new test is ideal for use in HD given its ecological validity, its ease of administration and the fact that it is so inexpensive; this makes it accessible for use in any population of HD patients and it doesn’t require any specialised custom computer software to interpret the results collected. To examine the validity of this new motor task, we tested a large group of individuals at pre-manifest and manifest stages of HD compared to healthy controls. Finally, we examined whether performance on this timed nut and bolt test was related to disease burden score (DBS). We now report for the first time that this simple inexpensive test can detect the earliest motor abnormalities in HD and performance correlates with disease burden scores across the entire disease, and so could be used to target those patients on the cusp of developing overt disease and as such may be suitable for use in new trials of disease modifying therapy.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from the regional NHS HD clinic at the John Van Geest Centre for Brain Repair between 2012 and 2014. Control subjects with no known neurological disease were recruited from friends or relatives accompanying patients to the clinic. Written informed consent was taken and the nut and bolt data was collected under ethical approval [Reference number:09/H0308/2] approved by Cambridgeshire 2 Research Ethics Committee. To collect additional data the task was also expanded to include patients seen in clinic as part of their routine clinical assessment and the collection of this data was classified as a service evaluation with the Patient Safety Unit at Addenbrooke’s Hospital (Project Register Number: 4256). The work was carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki 23. All preHD and HD participants had a positive genetic test for the HD mutation and were assessed using the UHDRS motor examination along with their total functional capacity (TFC) sub-section 24. PreHD participants were defined by having a diagnostic confidence level on the UHDRS of less than 4. Disease burden score was calculated using the CAG-Age Product Scale (CAPS) 25,26.

Nut and bolt task

The nut and bolt task was designed as a simple test to examine dexterity of the hands and fingers. The participants were asked to screw a nut onto a bolt in one direction using either the left or right hand; participants were not allowed to flick the nut and the hand holding the bolt had to remain static/stationary. The task consisted of 3 different sized nuts and bolts and was timed for both hands for all conditions. The task was performed using two test conditions; while the hands were supported resting on a table or unsupported, with the hands held in mid air. The task was timed using a standard stopwatch, the timer was started when the participant began screwing the nut onto the bolt and the timer was stopped when the nut reached the top of the bolt and could go no further. All those administering this test were instructed in how to carry out the test, but the simplicity of the task and the use of a simple stopwatch meant that no extensive training was needed.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software version 21.0. The main outcome for the task was the time it took for each participant to screw the nut onto the bolt using the left and right hand sequentially, both supported and unsupported. The independent variables were the three groups (Controls, PreHD, HD). Normality for all the dependent variables was tested using one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Group effects for variables that were normally distributed, such as age, CAG repeat, and UHDRS motor score were analysed using parametric tests (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc comparisons (T-test) with Bonferroni corrections where significance was present, all p values reported in the manuscript are already corrected. The group main effect was found to be significant. Variables with a skewed distribution, including data obtained from the nut and bolt assessments were first logarithmically transformed to obtain normality and analysed as above with the exception of the total functional capacity scores which were analysed using Mann-Whitney U tests. Partial Spearman correlations were performed using age as a covariate.

RESULTS

Participant demographics

A total of 83 participants were tested on this task and were divided into 3 groups: healthy controls, preHD and manifest HD participants (See table 1). As would be expected, manifest HD participants had a higher UHDRS total score [p < 0.001] and a lower TFC score [p < 0.001] than preHD participants. Healthy controls and preHD participants displayed similar baseline demographics (age) [p = 0.863], while participants with manifest HD were slightly older than control participants [p = 0.004] (Table 1).

Group

Age

CAG

UHDRS

TFC

Premanifest (n=24)

47.47 ± 2.66

41.73 ± 0.662

3.87 ± 0.975

12.26 ± 0.492

Manifest (n=27)

56.30 ± 2.62*

43.74 ± 0.796

24.07 ± 2.28#

8.78 ± 2.28#

Controls (n=32)

43.08 ± 3.18

–

–

–

Table 1. Table shows mean ± S.E.M. UHDRS: Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale: total motor score, TFC: total functional capacity. *indicates statistically significant difference when compared to controls whereas # indicates statistically significant difference when compared to preHD.PreHD participants show impaired performance in their performance with the non-dominant hand compared to controls.

PreHD participants show impairments in their performance with the non-dominant hand compared to controls.

PreHD participants were impaired on several aspects of the nut and bolt task when compared to the healthy controls, particularly when the non-dominant hand was being tested. Significant changes were observed with all sizes of the nut and bolt when the non-dominant hand was in the unsupported condition [small: p = 0.036. medium: p = 0.006 large: p = 0.001, table 2] and the large nut and bolt when the non-dominant hand was supported [p = 0.034]. In contrast, only one measurement was significantly different when testing the dominant hand [medium, unsupported: p = 0.009] indicating that dominant hand function is relatively well preserved at this stage of the condition (Table 2).

Anti-dopaminergic medication has no effect on performance on the nut and bolt task.

Anti-dopaminergic medications such as sulpiride and olanzapine are commonly used for treating the motor features of HD and hence may have an effect on performance in the nut and bolt task. In order to analyse the effect of such medications, we divided the preHD and HD participants into those who were receiving anti-dopaminergic medications and those who were not. Due to the nature of prescribing such medication for symptomatic relief of the motor features of HD, patients who were receiving such medication were in a more advanced stage of disease and hence were significantly older and a higher total motor score on the UHDRS [TMS: t = 3.29, p = 0.002, Age: t = 2.85, p = 0.006]. Therefore in order to minimise such confounding facts we included age and the total motor score as covariates in our analysis. Our results showed that there was no statistically significant difference in motor performance between those receiving anti-dopaminergic medication and those who were not [F = 1.75, p > 0.111].

Median (Seconds)

p values

Controls

PreHD

HD

Control-PreHD

PreHD-HD

Controls-HD

Non Dominant

Supported

Small

24

29

37

0.435

0.024

<0.001

Medium

19

25

31

0.076

0.04

<0.001

Large

14.5

24

21

0.034

0.093

<0.001

Unsupported

Small

19

25

36

0.036

0.032

<0.001

Medium

14.5

23

30

0.006

0.198

<0.001

Large

10

19

23.5

0.001

0.235

<0.001

Dominant

Supported

Small

23

25

43.5

0.152

0.002

<0.001

Medium

19.6

23

35.5

0.122

0.021

<0.001

Large

17.5

20

29

0.559

0.084

<0.01

Unsupported

Small

21

22

36.5

0.239

0.02

<0.001

Medium

16.5

21

32

0.009

0.052

<0.001

Large

13

15

26.5

0.14

0.006

<0.001

Manifest HD patients are significantly impaired in all domains of the nut and bolt task

Compared to controls the manifest group performed worse on all conditions tested while the preHD group appeared to demonstrate deficits under specific conditions (Table 2). In particular, whereas dominant hand function was not significantly different when comparing preHD to controls, manifest HD participants showed impairments compared to preHD when the dominant hand was tested with the small and medium nut and bolts whilst supported [small: p = 0.002, medium: p = 0.021] and the small and large nut and bolts whilst unsupported [small: p = 0.02, large: p = 0.006]. Performance with the small nut and bolt using the unsupported non dominant hand is significantly impaired at all stages of disease [preHD compared to controls: p = 0.036, HD compared to preHD: p = 0.032] (Figure 1) and correlates significantly with disease burden score (r=0.374), even when controlled for age [p = 0.021] (Figure 2). Finally all components of the nut and bolt task correlated with the patients UHDRS score in both preHD and manifest patients [small non-dominant unsupported nut and bolt: r = 0.494, p = 0.001].

Unsupported small nut and bolt in the non dominant hand in each group. Significance is denoted by asterisks, preHD compared to controls: p = 0.036, HD compared to preHD: p = 0.032.

Fig. 1: Non dominant unsupported hand measurements of time to complete small nut and bolt test for each group.

The time taken for the non dominant unsupported hand to complete the small nut and bolt task correlates with disease burden score [r = 0.374, p = 0.021]. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).![The time taken for the non dominant unsupported hand to complete the small nut and bolt task correlates with disease burden score [r = 0.374, p = 0.021]. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).](https://currents.plos.org/hd/files/2015/06/Slide12-300x225.jpg)

Fig. 2: Small nut and bolt measurement correlates with Disease Burden Score.

Discussion

The ability to detect, quantify and follow the loss of hand dexterity in HD is of importance for diagnosing patients at the earliest stages of disease, monitoring disease progression and evaluating the efficacy of novel treatments. Previous tests that have been proposed to be useful in this regard include finger 8,9 and hand tapping 10,11,12,13 with both tasks tracking disease course over time 10,27,28. However, while they capture changes in motor speed they do not measure changes in dexterity. In our new study, we introduced a novel task: the nut and bolt test, which we have now shown to be a useful way of measuring the impact of HD on fine motor coordination in a large group of patients. In particular, we have found significant differences in performance between preHD and controls in their non dominant hand with the dominant hand function remaining intact until later in the disease course. Furthermore the non dominant nut and bolt performance correlated with disease burden scores suggesting a relationship with proximity to disease onset. Therefore, the nut and bolt task may be both diagnostically useful and helpful for identifying premanifest patients at immediate risk of developing manifest disease who may also therefore be suitable for future trials of disease modifying therapy.

This finding of decreased performance in the non dominant hand is in agreement with the existing literature; specifically the TRACK-HD study that showed that there is a reduction in finger tapping in the non dominant hand over time 28. In the cohort of premanifest and early HD patients, it was found that tapping was one of the few functional measurements that had significant differences in preHD participants compared to controls and also progressed over time 28. Previously, differences in performance on simple speed tapping tasks in preHD and early stage HD cohorts have been correlated with cortical thickness, disease burden scores and motor scores 18 and in another study manifest and early HD patients tapping scores correlated with cognitive test scores, regional brain atrophy and UHDRS scores 19. All of which highlights that these simple motor measures are useful measures of disease stage with a pathology that can also be quantified.

Other motor tasks that have also be used in a similar way in HD include saccadic eye movements in which it has been shown that preHD patients can have a number of abnormalities that seem to track disease course over time 17. Quantitative measurements of tongue protrusion force in preHD and HD have also detected deficits in motor force 15 and in motor speech timing tasks in manifest HD patients showing impaired speech rhythm with defects in speech rate, increased pauses, impaired syllable repetition all of which correlated with motor tapping assessments 16. Other studies have shown slowing of rapid alternating movements in HD patients, as well as deficits in tapping and on peg insertion tasks 20. This confirms earlier findings where the peg insertion task was significantly different in HD patients compared to controls but failed to detect early changes in preHD groups 21. These tasks along with our simple task may suggest that the combination of speed and simple movements may highlight early deficits in HD, especially in the less dextrous non dominant hand. Indeed our nut and bolt task is unique in that is takes into account speed, dexterity, hand movements and motivation and as such may be more sensitive to the very earliest problems in HD which effects all of these functions. This would fit with imaging and post mortem data showing that those brain regions involved in these motor and affective activities are known to be abnormal in preHD and early HD including the striatum 28,29,30 the nucleus accumbens, pallidum 31 precentral and postcentral gyri as well as the supplementary motor area 32. Thus the clinical data sits well with the known neuropathology of premanifest and early HD.

Although, our test has many advantages including its cost and ease of administration and simple interpretation of results there are also some limitations with our study . This includes the absence of longitudinal data, and the need to trial it in larger numbers of patients and the problems of employing it in very advanced patients. However, this latter group are unlikely to be the target of new therapeutic interventions in the first instance, so this is less of an issue. Furthermore the nut and bolt task was timed manually using a standard stop watch and although the timing was not automated, each individual was trained in the same way and thus is unlikely to have contributed to any significant issues on the accuracy of the data collection. However using an automated timer may be a useful addition to our task. Finally our study captured a selection of un-medicated and medicated preHD and HD patients seen in our regional clinic, including HD patients on anti-dopaminergic medication such as sulpiride and olanzapine. Although we found no significant difference in our task in those patients on anti-dopaminergic medications compared to those who were not, we cannot rule out that this may effect their performance. In the future longitudinal studies that specifically address this issue are needed.

In summary, we describe a simple, inexpensive and robust task that is useful in defining disease onset as well as being of possible value in therapeutic trials of disease modifying therapies in both manifest patients and pre-HD patients approaching the time of phenoconversion. Furthermore it can be used in any clinic on its own or as part of a battery of tests to assess dexterity across all stages of HD given its simplicity and low cost.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Information

Lucy M. Collins and Faye Begeti contributed equally to this work.

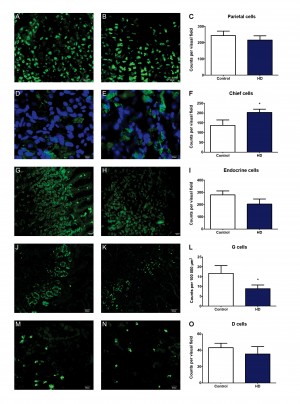

Introduction

Most studies into the pathology of Huntington’s disease (HD) focus on the basal ganglia and cerebral cortex1. However, mutant huntingtin is expressed throughout the body and abnormalities have been noted in peripheral tissues, not considered secondary to neuronal damage2,3,4.

Weight loss is one of the most common peripheral features of HD5,6. The underlying mechanisms are not, however, entirely known. Studies have indicated that weight loss is not secondary to inadequate nutrition, nor to hyperactivity5. Studies have instead suggested that loss of body weight results from changes in metabolism7 and also that reduced absorption of nutrients along the intestinal tract may play a role8. Work mostly performed in HD mouse models has demonstrated that tissues and organs that are involved in nutrient absorption are affected8.

In HD mouse models, huntingtin aggregates are abundantly present along the gastrointestinal tract9. The R6/2 mouse, the most widely studied transgenic animal model of HD, exhibits loss of enteric neuropeptides and altered gut motility8. Gastrointestinal function has never been investigated in HD patients, but there are indications that it may be affected. Patients are prone to suffer from gastritis and esophagitis10.

We therefore set out to study the gastric mucosa, using gastric mucosal biopsies as a tool, to look for abnormalities of enteric neurons and mucosal cells.

Materials and methods

Patient demographics

Patients with HD lose weight and have feeding difficulties. In some cases, this is managed by the insertion of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube. Ethical approval (MREC No. 08/WSE02/66) was given to approach patients after a clinical decision to insert a PEG. Gastric biopsies (from antrum and fundus/gastric body) were obtained from twelve HD subjects during the procedure to insert the PEG. Using the total functional capacity (TFC) rating scale11: 9 patients were at stage 5 (TFC = 0), one patient was at stage 4 (TFC = 1-2) and one patient was at stage 2 of the disease (TFC = 7-10) and had a TFC of 7. The patients were in long-term care and the formal CAG length report was not available for 8 patients (Table 1).

Control samples were obtained from 10 patients; 9 were being investigated for possible coeliac disease, one for altered bowel habit; the gastric mucosa was considered normal by the endoscopist. Ethical approval, covering England and Wales, was granted by the South East Wales Research Ethics Committee (08/WSE02/66) and confirmed in Scotland by the Scottish A Research Ethics Committee (08/MRE00/85). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Patient demographics

Group

N (M/F)

Mean Age (Range)

Control

10 (8/2)

55.5 (41-71)

HD

12 (6/6)

55.8 (25-73)

Immunohistochemistry

The gastric biopsies were fixed in formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin wax according to routine procedures.

Antrum and fundus (gastric body) were cut into 7 μm thick sections using a microtome (Leica SM2010R, Leica Biosystems Nussloch GmbH, Nussloch, Germany).

The different cell types were identified using immunohistochemistry; antrum sections – D-cells (anti-somatostatin antibody raised in rabbit; 1:3000 dilution, kind gift from Prof. J.J. Holst, Copenhagen University, Denmark), G cells (anti-gastrin; 1:2000 dilution raised in rabbit, kind gift from Prof. J.E. Rehfeld, Copenhagen University, Denmark) and fundus (gastric body) sections – parietal cells (anti-H+/K+ ATPase antibody raised in mouse; 1:1000 dilution, kind gift from Prof. A.J. Smolka, UCLA, USA), chief cells (anti-pepsinogen antibody raised in swine, 1:1000 dilution, kind gift from Prof. P.T. Sangild, Copenhagen University, Denmark), endocrine cells (polyclonal anti-chromogranin A raised in goat; 1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 and 0.25% bovine serum albumin. Prior to immunostaining, sections underwent antigen retrieval by boiling in citrate buffer using a microwave. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in the dark in a humid chamber. The next day, sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies for 1h at room temperature, followed by DAPI (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich, Stockholm, Sweden) for 10 minutes: DyLightTM 488-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-mouse, 1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., PA, USA; FITC-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-swine, 1:100, BioNordika, Stockholm, Sweden; Cy2-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-rabbit, 1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch; Cy2-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-goat, 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch. Control incubations were also included without the use of primary antibody; no staining was observed in these sections.