Method: 50 manifest HD patients were tested in social cognition and executive functions and each answered a self-report questionnaire about current status of perceived psychological distress (the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R)). Correlation analyses of test performance and SCL-90-R scores were made as well as stepwise linear regression analyses with the SCL-90-R GSI score and test performances as dependent variables.

Results: We found that less psychological distress was significantly associated with worse performances on social cognitive tests (mean absolute correlation .34) and that there were no significant correlations between perceived psychological distress and performance on tests of executive functions. The correlations between perceived psychological distress and performance on social cognitive tests remained significant after controlling for age, Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale-99 total motor score and performance on tests of executive functions.

Conclusions: Based on previous findings that insight and apathy are closely connected and may be mediated by overlapping neuroanatomical networks involving the prefrontal cortex and frontostriatal circuits, we speculate that apathy/and or impaired insight may offer an explanation for the correlation between self-report of psychological distress and performance on social cognitive tests in this study.

]]>Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal dominantly inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expanded CAG repeat on chromosome 41 and characterized by motor symptoms, psychiatric symptoms and cognitive decline. Once onset of motor symptoms has occurred, cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms also tend to be present 2,3,4,5. The cognitive deterioration in HD is thought to be related to dysfunction of the frontostriatal circuits due to gradual degeneration of the striatum6,7. Accordingly, the first signs of cognitive impairment are observed in cognitive functions associated with the prefrontal cortex such as executive functions and social cognitive functions4,8,9,10. Psychiatric symptoms are also commonly found even in the presymptomatic and earliest stages in HD, and a wide variety of psychiatric symptoms such as apathy, depression, irritability, anxiety, mania and obsessive compulsive symptoms can be seen11.

Performance on tests of social cognition and executive functions are often affected by psychopathology. Associations between social cognitive functions, executive functions and psychiatric symptoms have been investigated in both psychiatric and neurological disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, Parkinson’s disease (PD) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD)12,13,14,15,16,17,18. The most common finding being that greater degree of psychiatric symptoms are associated to worse performance on tests of executive functions and social cognition.

In two previous studies we have investigated performance on tests of executive functions and social cognition in a large cohort of HD patients in early-moderate disease stage and found a high frequency of impaired performances on tests of executive functions and social cognition2,4. Based on the associations between the presence of psychiatric symptoms and impairments in executive functions and social cognition found in other patient groups we wanted to investigate how subjective experience of psychological distress as reported by patients with Huntington’s disease is related to performance on tests of social cognition and executive functions.

Therefore the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between self-report of perceived psychological distress and performances on a battery of tests of executive functions and social cognition in a large consecutive cohort of HD patients. We wanted to investigate: 1) whether performances on tests of social cognition and executive functions are correlated, and 2) whether performances on tests of social cognition and executive functions are associated with degree of self-reported psychological distress. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare performance on a large battery of tests of social cognition and executive functions to self-report of psychological distress in HD.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from January 2012 to March 2013 from the Neurogenetics Clinic, Danish Dementia Research Centre, Rigshospitalet. Fifty HD patients with a CAG repeat ≥39, a Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale-99 total motor score (UHDRS-TMS) of >519, a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥ 24, and a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)20 score ≥ 20 were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were other neurological illness, ongoing alcohol or drug abuse and having a native language other than Danish. Table 1 shows the background information for the HD patients. All patients had gone through genetic counseling and had been informed of their genetic status prior to (and independently from) study enrolment. We have previously published results from the same cohort2,4,5,21 also including premanifest HD carriers, but since we found no impairments in social cognitive functions in our premanifest subjects we did not include them in the present study.

Table 1. Background information. Results shown as median (range)

Procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark(H2-2011-085), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment. All participants had a minimum of two planned visits. At one visit psychiatric screening and neurological examinations were performed. At the other visit neuropsychological testing was performed. The same physician and the same neuropsychologist performed all examinations. The examination by the physician and the examination by the neuropsychologist were performed blinded to one another.

Neuropsychological Testing

All participants were tested with an extensive three-hour battery of neuropsychological tests, including tests of attention, memory, visuospatial functions, executive functions and social cognition. For this study only tests of executive functions and tests of social cognition are included. The tests were administered in a fixed order. The education index score (range 8-17) was calculated as the sum of years of schooling (range 7-12) and the level of post-secondary education stratified into groups (range 1-5) based on the method previously used by Mortensen and Gad.22

Emotion Hexagon (EH)23: This test consists of 30 cards with pictures of morphed facial expressions of the six basic emotions: happiness, surprise, fear, sadness, anger and disgust. Each of the six emotions was represented with four pictures; each picture was morphed with either 10% or 30% of the neighboring emotions (e.g. happiness is morphed with either 10% or 30% anger or surprise). Between two neighboring emotions was a picture morphed with 50% of each emotion; these were not counted in the total raw score. A card with the six emotion words was presented, and each of the six emotions was explained before the pictures were shown to the participants and remained visible for them during the test. The pictures were shown in random order, and the participants were asked to choose which of the six emotions best described the facial expression. The pictures were shown only once, and no feedback was given. The test was scored as the total number of correct responses (0-24).

Emotion Evaluation Task (EET)24: The EET consists of 28 short videotaped vignettes (15-60 seconds) of actors interacting in everyday situations. In some of the scenes there is one actor only, and in other scenes there are two (the participant was then told on whom to focus). The participants were asked to choose whether the actor was displaying one of the six basic emotions: happiness, surprise, sadness, anger, fear or disgust or no particular emotion (neutral). The EET does not exist in a Danish version and therefore the video clips were shown without sound in order to exclude any influence of differences in English language abilities. Each video was shown once, and no feedback was given. The test was scored as the total number of correct responses (0-28).

Social Inference – Minimal (SI-M)24,51: The SI-M (Danish version: (Bliksted, Fagerlund, Weed, Frith, & Videbech, 2014) consists of short (15-53 seconds) videotaped vignettes with professional actors interacting in everyday situations. The exchanges are either sincere or sarcastic. The sarcastic vignettes are either with simple sarcasm, meaning that they are acted in such a way as to imply the opposite meaning to what is actually being said, or with paradoxical sarcasm meaning that the exchange of words is meaningless unless one understands that one of the actors is being sarcastic. After each video, the participant was asked four yes/no questions about the interaction. Correct answers to the questions for the sarcastic videos required interpretation of paralinguistic cues such as tone of voice and non-verbal cues such as posture and facial expressions. The test comprises part A2 and part B2. Part A2 consists of five videos of paradoxical sarcasm and ten vignettes that are either sincere or with simple sarcasm. Part B2 consists of exactly the same dialogue as the ten sincere or simple sarcastic videos from part A2 but with sincerity and sarcasm switched. For this study the participants were shown all 25 videos. Each video was shown once, and no feedback was given. Total number of correct yes/no answers (0-100) was used in the present study.

Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RME)25: The RME revised version consists of 36 photos of eyes expressing different emotional states. The participants were given four choices of words and were asked to pick the word that best described what the eyes expressed (e.g., serious, ashamed, alarmed or bewildered). In order to pick the correct emotion the participant needed to be able to attribute mental states to others thereby using Theory of Mind (ToM). The participants were also given a list of explanations of all the words in the test and were encouraged to look up the words if they felt uncertain of the meaning of a word. The number of correct responses was recorded (0-36).

Semantic fluency26: The participants were asked to name as many different animals as they could think of within one minute. It was emphasized that all types/categories of animals would be correct. Categories (e.g., birds) as well as specific animals (e.g., eagle) were accepted. The number of different animals named was recorded.

Lexical fluency26: The participants were asked to produce as many words as possible within one minute beginning with each of the letters F, A or S. It was emphasized that it could be all words in Danish except proper nouns. The number of different words produced with F, A and S were recorded and added together for a total score.

Lexical alternating fluency. This fluency test was developed by the researchers based on the most common first-letters in Danish apart from S and F. The participants were asked to produce as many different words as possible within one minute, alternating between words beginning with the letter K and words beginning with the letter B. It was emphasized that it could be all types of words except proper nouns. The number of correct responses was recorded, and improper alternations were counted as incorrect.

Semantic/lexical alternating fluency. This fluency test was developed by the researchers based on a category that was thought to be very broad and one of the most common first-letters in Danish apart from S, F, K and B. The participants were asked to produce as many different words as possible within one minute alternating between types of food and words beginning with the letter D. They were told that the former could be “anything you can eat”, and that the latter covered all words beginning with the letter D except proper nouns. The number of correct responses was recorded; improper alternations were counted as incorrect.

Trail Making Test B (TMT B)27:The participants were asked to connect circles alternating between numbers in numeric order and letters in alphabetical order. The time to completion was recorded.

Stroop interference test28: This 100-word version of the Stroop test consisted of a simple reading task and an interference test. In the interference test the name of the color and the color of the ink did not correspond, for example the word ‘blue’ could be written in green ink, and the participants were asked to name the colors instead of reading the words. Participants were instructed to complete the test as quickly as possible and to correct their mistakes. Only the time to completion for the interference test was used for analysis.

Self-report of psychological distress

Symptom Checklist -90-Revised (SCL-90-R)29: The SCL-90-R is a 90 item self-report inventory designed to reflect the current status of perceived psychological distress. The participant is asked to rate each of the 90 items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “very often” according to how much they experienced each symptom in the preceding week. The scoring is based on nine primary symptom dimensions: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism. Added together these yield three global indices of distress: Global Severity Index (GSI), Positive Symptoms Distress Index and Positive Symptom Total. For the current study raw scores were converted into T-scores standardized to a normative Danish sample stratified by gender50. Higher T-scores indicate greater degree of psychological distress. Only the GSI score was used for the association analyses in current study.

Statistical analysis

Results for the background variables are presented as medians and ranges. Pearson’s r and Spearman’s Rho (rs used for skewed distributions) were used to assess the level of significance of correlations between the cognitive tests and the SCL-90-R GSI scores and also to investigate the level of significance of associations between performances on tests of social cognition and executive functions. Lastly stepwise linear regression analyses were used with SCL-90-R GSI score as the dependent variable and scores on each of the social cognitive tests that were significantly associated with SCL-90-R GSI score as independent variables. For each regression analysis performances on all of the executive tests (Lexical fluency, Semantic fluency, Lexical alternating fluency, Semantic/lexical alternating fluency, Stroop test and TMT B), age and UHDRS-TMS were also included as independent variables. Plots of residuals were used as model control and the alpha level was set to .05 (two-tailed).

Results

Table 2 shows the median and interquartile range for performance on all tests of executive functions and social cognition, as well as the median and interquartile range for the standardized T-scores on the GSI and the nine symptom dimensions of the SCL-90-R.

Table 2. Scores for HD carriers on the cognitive tests and the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised Global Severity index and the nine primary symptoms dimensions. Results shown as median (interquartile range)

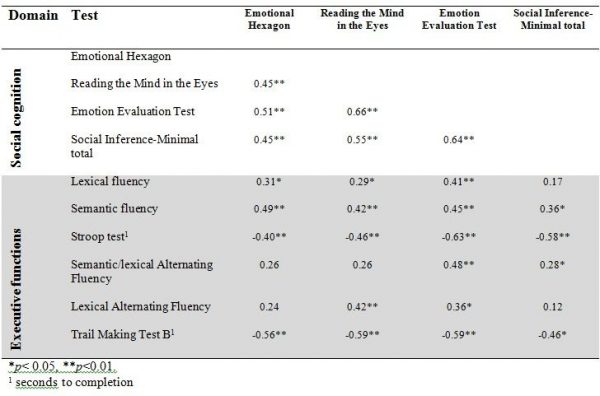

Table 3 shows the correlations between social cognitive tests and tests of executive functions. As expected we found that performances on all four social cognitive tests were significantly correlated with each other. Performances on all four social cognitive tests were also significantly associated with performances on tests of executive functions (mean correlation .24).

Table 3. Correlations between tests of executive functions and tests of social cognition. Results shown as Spearmans Rho.

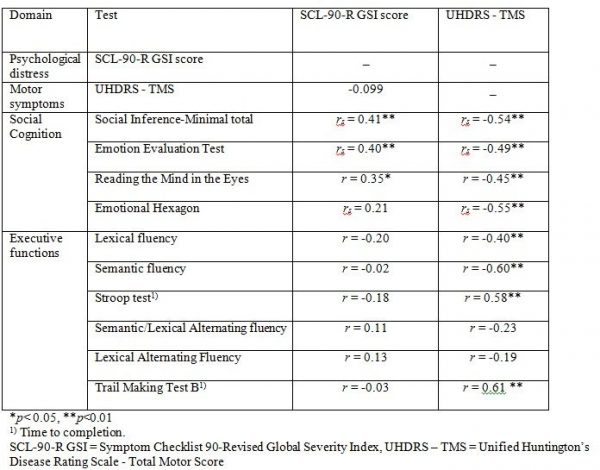

Table 4 shows the correlations between the SCL-90-R GSI score and the UHDRS-TMS and the tests of executive functions and social cognition. We found a significant correlation between the SCL-90-R GSI score and scores on three of the four social cognitive tests (the SI-M total, the EET and the RME), such that better test performance was related to more perceived psychological distress. The mean overall correlation was .34. By contrast, none of the correlation coefficients between the SCL-90-R GSI score and the tests of executive functions reached significance. Motor symptoms were not significantly correlated to SCL-90-R GSI score, but were significantly correlated to performance on most tests of executive functions and social cognition.

Table 4. Correlations between SCL-90-R GSI score, UHDRS – TMS and test of executive functions, social cognition. Results shown as Pearsons r (r) or Spearmans Rho (rs).

Table 5 shows the result from the stepwise linear regression analysis. We found that the correlation between score on SCL-90-R GSI and RME, EET and SI-M score remained significant after including performances on all of the executive function tests (Lexical fluency, Semantic fluency, Lexical alternating fluency, Semantic/lexical alternating fluency, Stroop test and TMT B), age and UHDRS-TMS in the analysis. We also found a significant negative effect of age on SCL-90-R GSI score.

Discussion

This study investigated whether performances on tests of social cognition and executive functions were associated with perceived psychological distress in a group of HD patients. Since greater degree of psychiatric symptoms such as depression has been negatively associated with both social cognitive skills and executive functions, we were surprised that more perceived psychological distress was significantly associated with better performances on social cognitive tests and that less perceived psychological distress was associated with worse performance on social cognitive tests. The correlations between psychological distress and tests of executive functions were non-significant. Furthermore, the correlations between self-reported psychological distress and performance on social cognitive tests does not seem to be an artefact of those being furthest in the disease progression performing worse and reporting fewer psychological symptoms since the associations remained significant after controlling for age, UHDRS-TMS and performance on tests of executive functions. This means that for our cohort of HD patients feeling less psychologically distressed themselves was associated to worse performance on tests of the ability to recognize emotions, ToM and sarcasm in others. This is an interesting finding that may help to understand the interpersonal problems often associated with HD. It may be helpful for clinicians and caregivers to know that feeling little psychological distress oneself may also influence the ability to recognize distress in others.

We used a self-report measure of psychological distress, and it is important to remember that self-report of psychological distress in HD may be influenced by poor insight, which is a common feature of HD30,31. This means that although the patients themselves do not report having psychiatric symptoms this might not be true from a clinician or caregiver perspective. This means that our findings do not necessarily indicate that poor social cognition is genuinely associated with fewer psychiatric symptoms in patients with HD from an outside perspective. Instead, our findings may reflect a relationship between insight and emotion recognition as has been demonstrated in related disorders32 and a close connection between our understanding of the self and others33.

Social developmental research has long posited the idea that representations of the self and other are closely connected34, and research in neuroscience has supported the view of common representation networks between self and other involving, in particular, the parietal cortex, superior temporal sulcus, limbic areas, striatum and orbital and medial areas in the prefrontal cortex33,35,36,37. Since representations of others are closely connected to our representation of the self, it could be speculated that loss of insight and flattening of affect in oneself may be associated with less sensitivity to others’ emotional states as well, leading to a state of being ‘comfortably numb’. We speculate that an alternative explanation of our results may be that a flattening of affect (from here on referred to as ‘apathy’) and impaired insight has led to low self-report of psychological distress in our cohort and that this was related to the weaker understanding of others (i.e. poor social cognitive skills including emotion recognition).

Impaired insight and apathy are well-known features of HD31,38,39 and other psychiatric and neurological disorders affecting the prefrontal cortex and frontostriatal circuits such as schizophrenia, PD and FTD. Apathy ratings have been associated with white matter changes in the orbitofrontal cortex in HD, and in both PD and FTD apathy has been associated with areas of the striatum and frontostriatal circuits13,17. In schizophrenia negative symptoms have been inversely associated with striatal activation40. These studies suggest that social cognition, insight and apathy may in part be mediated by overlapping neuroanatomical networks involving the prefrontal cortex and frontostriatal circuits. Thus HD may be a relevant condition in which such associations can be studied.

Studies of patients with HD, schizophrenia and FTD suggest a reciprocal relationship between insight and apathy (or negative symptoms), such that higher scores of apathy or negative symptoms have been associated with impaired awareness of these symptoms30,41,42. In fact, impaired insight has been associated with better mood in both HD and schizophrenia meaning that patients with less awareness of illness and symptoms has been associated with fewer symptoms of depression, whereas greater self-awareness has been associated with higher depression scores14,42,43,44. These findings support the view that apathy and lack of insight are closely connected and they also point in the direction of patients with symptoms of apathy being expected also to have poor self-awareness and therefore to report neither apathetic symptoms nor psychological distress in general.

Impaired insight and higher apathy scores have been found to be associated with worse performances on social cognitive tests in FTD, PD and schizophrenia13,41,42,45,46. One study in FTD found that patients’ own ratings of apathy were positively correlated to ToM whereas the caregivers’ apathy ratings were negatively associated with ToM performance13, indicating that greater awareness of apathetic symptoms was associated with better social cognitive skills. This finding may reflect the close connection between representations of the self and other and is in line with our results indicating that patients with better self-awareness also have a better understanding of others’ emotional states and vice versa. We found no associations between self-report of psychological distress and performance on tests of executive functions. This was somewhat surprising since psychiatric symptoms such as depression has often been associated to impairment in executive functions. There may be several different explanations for this finding. It may be that the tests used in this study are not sensitive to the type of executive dysfunction associated with psychiatric symptoms. It could also be that the types of psychiatric symptoms that are associated with executive dysfunctions are not well measured by the SCL-90-R. In a study by Thompson et al. 47 they found that only apathy was significantly associated with impairment in executive functions in HD.

No other studies that we know of have found significant correlations between self-report of psychological distress and performance on social cognitive tests in HD. Two studies have investigated the correlation between alexithymia and emotion recognition and ToM in HD but found no significant correlations48, and one other study found no significant associations between performance on a ToM task and psychiatric symptoms on the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale in HD49. Discrepancies between our results and previous findings may be explained by different methodological approaches, and these previous studies had small sample sizes compared to our study.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. In an exploratory study like this was, there can be quite a lot of statistical comparisons and thus a chance of false positive findings. The use of a self-report measure of perceived psychological distress may have been misleading, since some HD patients are known to show poor awareness of their symptoms. Future research should add ratings from caregivers or clinicians to overcome this problem and to get more information about the relationship between social cognitive performances and insight in HD. Also an apathy rating scale or a scale for rating negative symptoms, would have helped to clarify the mechanisms for our findings. Future studies should apply apathy ratings to investigate the association between social cognition and apathy in HD.

Other limitations to the study relate to the tests used. The Danish version of TASIT was developed for research purposes and it has not been standardized and validated. This must, of course, lead to caution when interpreting results. Sarcasm as a part of everyday interaction is somewhat culture specific and thus generalization to all other cultures may be limited. The EET of the TASIT does not exist in a Danish version and thus was used without sound. The clinical impression of performances on this test was that it was still meaningful and there were no significant differences between healthy controls and premanifest HD carriers on performances on the EET in a previously published study (ref). Although our evaluation was that the test was still meaningful, the different use of the test from its original form requires caution when interpreting the results.

Conclusions

We found significant associations between self-report of psychological distress and performances on social cognitive tests but not on tests of executive functions. According to our findings HD patients that feel less psychologically distressed themselves perform worse on tests of the ability to recognize emotions, ToM and sarcasm in others. This is an interesting finding that may be of importance for understanding the interpersonal problems often associated with HD. We speculate that one mechanism for this finding may be that shared representations of self and other as well as insight and apathy may be closely connected and may be mediated by overlapping neuroanatomical networks involving the prefrontal cortex and frontostriatal circuits. Therefore we speculate that a flattening of affect or apathy and impaired insight has led to low self-report of psychological distress in our cohort and that this was related to the weaker understanding of others (i.e. poor social cognitive skills including emotion recognition).

Competing Interests Statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Corresponding Author

Ida Unmack Larsen ([email protected])

Project Aim: The aim of this cross-sectional study is to assess QoL among Cypriot patients with HD, using a standardized health-related QoL questionnaire.

Materials and Methods: A generic QoL questionnaire was used, namely EQ-5D, which is a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcomes and is applicable to a wide range of health conditions. The study was conducted with 34 patients, which represented 46% of the Cypriot HD patient population.

Results: Ability of patients to care for themselves and to carry out usual activities were reported to be most severely affected (37.5% and 40.6% replying “Severe Problems” respectively). Mobility and psychosocial well-being were also affected to a lesser extent (25.0% and 15.6% replying “Severe Problems”). Interestingly, in the anxiety/depression scale, 77.8% of asymptomatic patients reported “Some Problems”. Half of the patients did not experience pain or discomfort but 40.6% reported “Some Problems” and 6.3% reported “Severe Problems”. The Health Status as perceived by the patients was found to be moderately to severely affected. In multivariate ordinal regression analyses, age at onset and disease duration significantly impacted on self-care. In addition, disease duration was significantly associated with mobility, self-care and usual activities scales. No significant determinants were evidenced for Pain/Discomfort and Anxiety/Depression. Lastly, age of onset was found to be the only significant determinant of the cumulative QoL score (Range=5-15).

Conclusions: Age at onset and disease duration were found to severely affect the QoL of Cypriot HD patients, and more specifically their mobility, ability to self-care and perform usual activities. The percentage of patients reporting “Some Problems” in the Pain/Discomfort category can be explained by the direct translation of the word as presented in the questionnaire, indicating the need for language specific instruments. Perhaps more noteworthy is the phychosocial burden on even asymptomatic patients, which needs to be acknowledged and managed to improve their quality of life.

]]>Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a fatal progressive neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS), in which patients experience profound motor, behavioural and cognitive symptoms1. Despite the enormous burden of this disease on the quality of life (QoL) of patients and their families, there is very limited evidence on this topic.

HD is a devastating disorder and besides progressive chorea is also characterized by rigidity and dementia2. A wide range of psychiatric disturbances and behavioral problems is also associated with the disease, which include depressed mood, anxiety irritability, apathy and psychosis3. It is important to catalogue the entire range of possible symptoms because they have a substantial impact on the ability of individuals to go about their daily activities, and the disease is known to cause severe disabling and distress4.

The inheritance type of disease is autosomal dominant, i.e. children of HD gene carriers have a 50% chance of inheriting the gene5. The mean age at onset of symptoms is 30-50 years, and leads to death within 17–20 years 6, where the juvenile HD appears in individuals under the age of 20, and is usually transmitted paternally7.

The genetic mutation is determined in chromosome 4p16.3, which encodes the huntingtin protein (348-kDa). A genetic alteration in the HTT gene causes HD due to the increased number of repetitions of “triplet” nucleotides ‘Cytosine Adenine Guanine’ (CAG)8, which is associated with accumulation of an abnormal misfolded protein. This can impair cell function and lead to neuronal loss and it affects large number of pathophysiological pathways, i.e. a proteinaceous aggregation, which interferes with cellular trafficking9.

Presenting the phenotype of HD patients, HD belongs to the family of movement disorders, which can be divided into two categories; hyperkinesia, which is defined as involuntary movements, classically chorea or not rhythmic movements, and hypokinesia of voluntary and automated movements10. Motor impairment is usually amongst the first symptoms of HD patients, and in progressive stages is characterized by dystonia, rigidity and bradykinesia5.

Behavioural alterations in HD often cause the most distress both patients and their families and are therefore often central in the practical clinical management of patients11. The most common psychiatric symptoms, which occur as part of the disease, include depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (3). Moreover, recent findings from Wetzel et al.12 show suicide rates were reported to be 9.5% in HD individuals, and suicidal ideation 26.5%. One of the leading causes of death of HD patients is suicide, another being pneumonia13.

The final important aspect of HD in patients is cognitive impairment. HD is associated with significant memory decline in early stages, and even poorer presentation in later stages, compared to healthy individuals 14,15.

HD occurs in all racial groups but a higher prevalence was observed in Europe, North America, and Australia with 5.70 cases per 100.000, with a much lower in prevalence in Asia of 0.40 per 100.000 16. Prevalence of HD in Cyprus in 2012 was 7.22 per 100,000, while the incidence was 0.62 per year. Prevalence in Cyprus is therefore higher than the respective worldwide figure, although the sample size is too small to make definitive statements.

Quality of Life (QoL) measures provide an effort to improve care. Clinical research sometimes considers these as outcome measures, but clinical practice has not, thus far, made significant use of them (Higginson and Carr 2001). QoL has potential uses in aiding routine clinical practice. They can be used to obtain a ranking of problems according to severity, maintain focus on patients’ main complaints, and identify less obvious issues, particularly psychological ones, improving clinical cooperation and monitoring treatment performance. They can also be used in clinical audit and in clinical governance17. Overall, QoL measures can be a predictor of treatment success, and several studies have shown that factors such as QoL, physical well-being, mood and pain are of prognostic importance18.

There is an increasing body of research associated with the negative impact of HD in the QoL of patients. The majority of studies conclude that HD has an adverse effect on patients’ physical and psychosocial well-being, where the effect on the latter is greater19,20,21. A recent study has demonstrated that people with progressive neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer Disease, Parkinson Disease or HD, suffer from negative mood swings and have lower QoL scores. The findings show that HD patients exhibited the most severe illness-related symptoms, and the greatest effects on mood and their QoL. In particular, HD patients had the least control over their bodily functions, found the greatest difficulty in tasks requiring cognitive functions, and experienced the greatest number of psychological symptoms, as well as high levels of confusion21.

Even compared to other neurodegenerative disorders, neuropsychiatric symptoms in HD have been found to have a much greater effect on QoL. In particular, behavioural alteration is prevalent and psychopathology is affected more severely21,22. Considering the severity of HD, the fact that currently there is no cure for the disease, and the high prevalence of HD in Cyprus, more studies are needed to assess QoL among Cypriot patients, in order to improve our knowledge about their living conditions and to assist the management of this condition.

The aim of this cross-sectional study was to assess QoL among Cypriot patients with Huntington disease, using a standardized health-related quality of life questionnaire. The specific objectives of this study were to assess the quality of life of Huntington disease patients visiting the Cyprus Institute of Neurology and Genetics for follow-up and treatment and to investigate socio-demographic and clinical determinants of quality of life among these patients (i.e. gender, current age, age at onset of disease, age tested, disease status, parent-of-origin and number of repeats in HD allele).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and recruitment of participants

The present study took place at Neurology Clinic D, at the Cyprus Institute of Neurology and Genetics (CING). Ethical approval was granted by the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (ΕΕΒΚ ΕΠ 2013.01.06).

The target sample for the project comprised of all alive HD patients registered at CING (n=62). From those, it was possible to contact 37 participants. The remaining 25 were either too severely disabled to come to CING for completion of the questionnaire or their treating physicians suggested that these particular patients had refused any contact from CING previously. Out of those 37, 3 refused to participate, thus the total number of participants for the current study was 34. Participants were recruited at CING during routine visits, and after having signed a Consent Form .

The only inclusion criteria for patients were to have a confirmed diagnosis of HD and to have given consent for participation, via the aforementioned Consent Form. Participants were already aware of their condition during data collection.

Once participants had read the information in the Consent Form and signed the forms, they were asked to answer the EQ-5D Questionnaire, in order to assess their QoL. All questionnaires were anonymized using the patient’s unique CING medical record number, which was written on the questionnaire.

For patients at advanced stages of HD who may not have been in a position to read and comprehend the Consent Form and the Questionnaire due to cognitive impairment, a proxy version of the questionnaire was given to a proxy for completion.

HD patients who were unable to visit the CING either due to the severity of their illness or due to personal reasons were asked to participate in a telephone interview by their doctors. Consent Forms were given to them upon visiting the CING for their routine appointment.

Assessment of Quality of Life

A generic QoL questionnaire, the EQ-5D, was used, which is a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome and is applicable to a wide range of health conditions. The type of EQ-5D questionnaire that was used was the EQ-5D-3L, as this was the only version translated and validated in the Greek language. EQ-5D-3L consists of two sections; the EQ-5D descriptive system and the EQ VAS.

Scoring the EQ-5D Descriptive System

The first section in the questionnaire, the EQ-5D descriptive system, comprises 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care (intended to capture the ability of patients to, e.g. wash or dress their selves), usual activities (intended to capture the ability of patients to work, study, perform housework and engage in family or leisure activities), pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression (hereafter ‘’5D’’). Each dimension has three levels (hereafter ‘’3L’’), which are defined as: no problems (level 1), some problems (level 2), and severe problems (level 3). The respondent was asked to indicate his/her health state by ticking in the box against the most appropriate statement in each of the 5 dimensions. This decision resulted in a 1-digit number expressing the level selected for that dimension. It should be noted that only one response was accepted for each dimension.

A cumulative QoL score was constructed by adding up all the values of the EQ-5D Descriptive System state (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/ discomfort and anxiety/depression). The sumulative QoL score could range from 5 (no problems in any scale and thus a good QoL) to 15 (severe problems in all scales and thus a bad QoL).

Scoring the EQ VAS

The second section, the EQ VAS, uses a visual analogue scale to capture the respondent’s self-assessment of their health on a continuous scale, where the higher endpoint is labelled ‘best imaginable health state’ and the lower endpoint reflects the ‘worst imaginable health state’. This information was used as a self-rated quantitative measure of health.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical software programme STATA version 12 SE used to perform the required descriptive and inferential analysis.

The main characteristics of participants including demographic (gender, disease status and parent-of-origin) and clinical characteristics (current age, age at onset, age tested, years since onset and number of repeats of mutant HD allele) were first examined. In addition, the variables for each of the five dimensions of the EQ-5D Descriptive System were analysed, along with the cumulative QoL score and the EQ VAS score.

Univariate associations between the different demographic and clinical characteristics and the QoL measures were assessed using one-way ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis, and Fisher’s exact tests depending on the nature of the variables examined.

Lastly, multivariate models were used to assess the combined effect of demographic and clinical characteristics on QoL outcomes. Given the ordered nature of the responses in each outcome of the EQ-5D Descriptive System, ordinal logistic regression was used. The cumulative QoL score and the EQ-VAS scores were categorized into 2 groups (above/below the median) and were analysed using logistic regression, because of their non-linear nature and the failure of several common transformations to normalize them. Because of collinearity between current age and years since onset (r=0.4305, p=0.005), only years since onset was included in the models to reflect disease duration. Keeping current age instead of years since onset, did not alter the results indicating that both variables equally well reflect disease duration. In addition, parental mode of inheritance and gender were not significantly associated with any outcome and were thus removed from the models to achieve a better fit. Lastly, because the majority of asymptomatic patients reported No Problems in all scales, the multivariate analyses were only performed on symptomatic patients (n=23).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Cypriot HD patients

All patients recruited met the inclusion criteria. However, two patients were unable to complete the questionnaire and a proxy version of the questionnaire was filled in by their spouses. Due to the likely heterogeneity between patient and carer perspectives, especially when patients are severely functionally impaired, these two patients were excluded from further analyses. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the remaining 32 patients who took part in the study. The majority of the patients were women 62.5% (n=20), while men were 37.5% (n=12). The median age of the patients at the time of the study was 52.5 years.

Among these 32 patients, 72% were symptomatic HD patients, while the other 28% were asymptomatic HD patients. For the 23 symptomatic patients, the median age at onset was found to be 43 years, which was close to the median age of testing of 41.5 years. The majority of the patients, 64.5%, had inherited the HD gene maternally. Finally, of the total 32 patients that were genetically tested, the median number of the normal allele was 17 CAG repeats, whereas the median number of the mutant allele was 43 repeats.

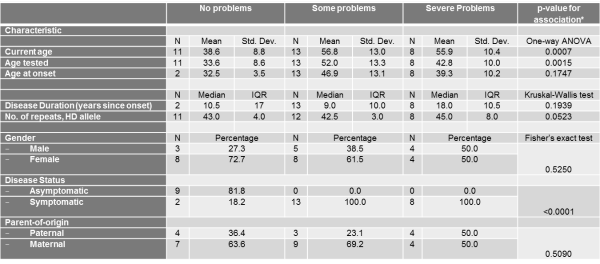

Table 1. Baseline Patients’ Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Cypriot HD patients

Quality of Life among Cypriot HD patients: The EQ-5D Descriptive System among Cypriot HD patients

The results of the EQ-5D Descriptive System, which was comprised of five dimensions each of which has three levels, are presented in Table 2.

Over 40% of the patients had mild problems with their motor function, while a lower percentage (25.00%) had experienced motor impairment (i.e. severe problems). Surprisingly, the vast majority patients (81.25%) were split equally between reporting no problems and severe problems with their self-care. However, the majority of patients (40.63%) had severe problems in performing their usual activities, which included work, study, housework, family or leisure-related activities. On the other hand, 93.75% had either reported some or no pain. Lastly, the majority of the HD patients (>70%), had experienced some anxiety or depression, with slightly more than 15% experiencing severe problems.

Table 2. Frequency Proportions for each score of the EQ-5D Descriptive System among Cypriot HD patients

Looking at the cumulative EQ-5D Quality of Life score, 50% of HD patients had a score below 9.5, and 25% of HD patients had a score above 12, which indicates a poor QoL.

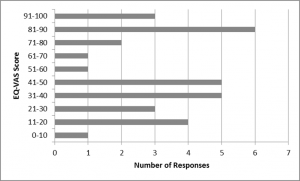

Fig. 1: The EQ-VAS scores of Cypriot HD patients, a self-assessed health measure

Quality of Life among Cypriot HD patients: The EQ- VAS score among Cypriot HD patients

The EQ-VAS score indicated that contrary to what was expected, a large number of patients reported a perfect health status. On the contrary, one patient reported an EQ-VAS of lower than 10%. The median (IQR) was found to be 50 (60).

Determinants of Quality of Life among HD patients : Univariate analyses per scale outcome of the EQ-5D Descriptive System

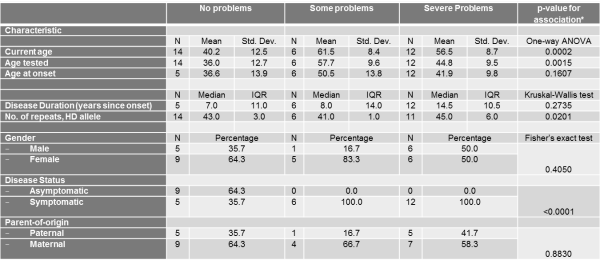

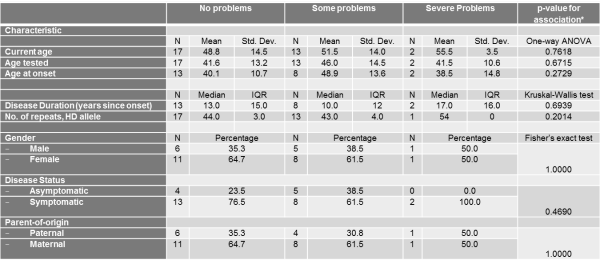

Univariate associations between the different scales of the EQ-5D Descriptive System and different demographic (gender, current age, disease status and parent-of-origin) and clinical characteristics (age at onset, age tested, and number of repeats of mutant HD allele) are shown in Tables 3-7.

Only current age, age tested, and disease status were significantly associated with the mobility score (Table 3). The severity of problems was positively associated with age (p=0.0007) and age tested (0.0015). Also, as expected, asymptomatic patients all reported no problems with their mobility in contrast to symptomatic patients (p<0.0001).

Table 3. The association between the mobility Scale of the EQ-5D Descriptive System and different socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 4. The association between the self-care Scale of the EQ-5D Descriptive System and different socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 5. The association between the usual activities Scale of the EQ-5D Descriptive System and different socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Similarly, current age and age tested were significantly associated with the self-care score (Table 4) and current age was also associated with the usual activities score (Table 5). The severity of problems was positively associated with current age (p for self-care=0.0002, p for usual activities=0.0054) and age tested (p for self-care=0.0015). Also, as expected, disease status was associated with self-care and usual activities scores (p for self-care<0.0001, p for usual activities<0.0001). Asymptomatic patients all reported no problems with self-care and all but 2 asymptomatic patients reported no problems with usual activities. Self-care score was also positively and significantly associated with number of repeats in HD allele (p=0.0201).

With respect to Pain/Discomfort and Anxiety/Depression, no demographic or clinical characteristic demonstrated significant associations (Tables 6-7).

Table 6. The association between the pain/discomfort Scale of the EQ-5D Descriptive System and different socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 7. The association between the anxiety/depression Scale of the EQ-5D Descriptive System and different socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Determinants of Quality of Life among HD patients : Multivariate analyses per scale outcome of the EQ-5D Descriptive System

From multivariate analyses, it became evident that age of onset was independently and significantly associated with the self-care scale. For each year older a subject was at disease onset, they had 46% increased odds of reporting some or severe self-care problems compared to no problems. The significance of age at onset on the self-care scale may reflect the influence of current age since these two variables were highly collinear.

Disease duration was perhaps the most important determinant, since it was significantly associated with the mobility, self-care and usual activities scales. For each additional year of disease duration, patients were 19%, 33% and 22% more likely to report some or severe problems for the mobility, self-care and usual activities scales respectively. For these three scales, age tested did not retain the significance demonstrated in the univariate analyses probably due to the stronger effect of disease duration on the scales.

Similar to the univariate analyses, for Pain/Discomfort and Anxiety/Depression scales, no demographic or clinical characteristic demonstrated significant associations (Table 8).

Table 8. Multivariate analyses using ordinal logistic regression between demographic and clinical characteristics and each EQ-5D Descriptive System outcome

Determinants of Quality of Life among HD patients : Cumulative Quality of Life Score

Of the independent demographic and clinical characteristics examined, only current age and age tested were significantly associated with having a cumulative QoL index score above median. However, in the multivariate model, where current age was not retained, and contrary to what was expected from the multivariate analyses of the individual EQ-5D Descriptive System scales, only age at onset was statistically significantly associated with the cumulative QoL. More specifically, for each one-year increase in age at onset, a subject had 85% increased odds of reporting a QoL score above 9.5, which translates into worse quality of life.

Table 9. Univariate and multivariate analyses between demographic and clinical characteristics and the cumulative Quality of Life score

Determinants of Quality of Life among HD patients : The EQ-vas scale

In univariate analyses, current age and age tested were significantly and negatively associated with having an EQ-vas score above median. For each one-year increase in current age, each individual had 13% decreased odds of reporting an EQ-vas score above 50, demonstrating decreased self-assessment of their health. The respective percentage for each one-year increase in age tested was 9%. Most importantly, symptomatic disease status also decreased by 95% the odds of reporting an EQ-vas score above median. However, in the multivariate model in symptomatic patients, none of these characteristics retained their statistical significance. This might reflect that onset of disease might in fact have a greater impact on health status self-assessment than do mobility, self-care, and usual activity problems which are associated with age at onset and disease duration.

Table 10. Univariate and multivariate analyses between demographic and clinical characteristics and the EQ-vas score

Discussion

Overall Quality of Life

This analysis determined that over 40% of the Cypriot HD patients showed particularly severe impairment in their ‘self-care’ competence and their ability perform their ‘usual activities’ . These results are in agreement with the study of Helder et al. 200119, which using a different questionnaire on 77 Dutch patients, concluded that there was severe impact of HD on the ability of patients to carry out their usual activities.

Helder’s results also showed that a large percentage of the patients reported difficulty in maintaining productive employment due to deterioration in alertness faculties (e.g., forgetfulness, attentional and problem-solving deficits) and problems in the physical domain, which contributed to their inability to continue working. A significant percentage of patients also reported severe impairment in the categories of “home management” and “recreation and pastimes”. However in the study of Helder et al., there was a small percentage of patients reporting problems with their ability to eat (which can be considered as a proxy for self-care in the EQ-5D system), which is in contrast to the study of the Cypriot patients’ QoL. As in this study, other studies have shown that the impact of HD on the usual activities of patients and on their self-care abilities becomes more severe with progressive stages of the disease23.

In this study, the majority of the patients also reported moderate problems in their mobility status, as expected. HD belongs to the family of movement disorders 10 and in progressive stages is characterized by dystonia, rigidity and bradykinesia5. In fact, motor impairment is a profound symptom of HD patients. More specifically, it includes falls, gait and sleep disturbances24,25. These results are in agreement with several other studies assessing the motor impairment by questionnaire in HD patients, which concluded that motor symptoms are negatively associated with the QoL of HD patients 19,20,24.

However, in the above mentioned studies 192024 , the major factor implicated in the poor QoL of patients is the psychological factor. More specifically, these studies concluded that HD patients showed more severe impairment on the psychosocial domains than in the physical domains. In particularly, they assessed determinants such as ‘depressive mood’, ‘emotional behaviour’, ‘alertness behaviour’ and ‘psychosocial dimension’. This is in agreement with our study since a high percentage of the Cypriot patients (over 60%) reported moderate anxiety/depression status. This is an expected finding in the context of HD studies, since the behavioural alteration in HD patients is a common symptom11. Moreover, a study from McCabe et al. (2009)21, assessing the QoL of among three motor diseases (in particularly, AD, PD and HD), showed that HD patients experienced the greatest effects in their mood and QoL. Interestingly, even 77.8% of asymptomatic patients reported a moderate anxiety/depression status indicating the psychosocial burden of the disease even before its onset.

Furthermore, less than 6% of Cypriot patients reported severe ‘pain or discomfort’ problems, while approximately 45% patients reported moderate problems (Figure 4). Regarding pain effects, a study from Tomaaso et al. (2011)26, which evaluated pain perception in HD patients, concluded that pain is not a common symptom in HD. This is confirmed with other studies, were bodily pain was negatively related to the illness perceptions of HD patients27,28. This symptom is in contrast to other neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD29.

Regarding the extent of ‘discomfort’, it is important to mention that the word ‘discomfort’ has an ambiguous meaning in Greek. The direct translation of the word as presented in the questionnaire may have influenced the response of the participants because in the Greek language, the word points towards both physical and mental discomfort. This is in contrast to the English word, which reflects physical uneasiness. This can perhaps explain some of the variation in the percentages of patients selecting moderate and severe problems in this category. Since pain is not common symptom of the disease, and as per the Cypriot patients’ responses, the state ‘discomfort’ should be consider as both mental and physical20.

Assuming that, to the patients’ understanding, the word ‘discomfort’ indicates both mental and physical discomfort in Greek, this subsection further confirms that HD has an adverse effect on Cypriot patients’ psychosocial well-being. This result could be due to the fact that psychosocial well-being is not only determined by illness-related factors, such as motor or cognitive disabilities, but primarily by psychological concomitants of that illness, including the way in which patients cope with their disease.

The median Cumulative QoL was found to be 10 indicating moderate problems in all scales and thus a moderate QoL. This is in agreement with similar studies, conducted, however, using different questionnaires, which concluded that HD has a severe impact on patients’ physical and psychosocial well-being (i.e. depressive mood, anxiety), with the latter being more prominent19,20,24.

On the other hand, the EQ-vas score, which can be considered as an aggregate self-reported health status of the patients, ranged from average to poor (Figure 8). The EQ-vas score amongst Cypriot patients does not seem to follow a normal distribution, since a large number of patients reported a perfect health status. It is important to note that in this study, although there was proxy version of the questionnaire, which was given to patients’ relatives for completion in the case where patients had some cognitive impairment, there were also participants who answered the questionnaire and had some form of cognitive disability. This was confirmed by the patients’ doctors. It resulted in some patients, who were already in later stages of the disease, bound to a wheelchair, reporting a Health Status of 100%. This is possible because HD patients in progressive stages, who had experienced severe mobility impairment, are likely to experience cognitive impairment as well23. This has occurred because in our study we did not use a ‘mini mental stage examination’, which is commonly used in neurodegenerative studies, including HD30,31.

Determinants of Quality of Life – Demographic Determinants

Gender

Our sample was comprised of more women than men (Table 1), but this is unlikely to have significantly influenced the results, given what is known about HD and, in particular, also QoL gender comparison. Starting with the effect of gender examined in the study, we related it to the categories of the EQ-5D Descriptive System, Cumulative QoL and the EQ-vas scale, however, no association was found to be significant, as was expected from a study from Mahant et al. (2003)32, which evaluated the clinical correlation and the progression of the HD, and did not find any association between the rate of progression of the disease (thus, the poorest QoL) and the sex of the affected individual.

Current Age

Regarding the age of the patients, the association of age with mobility, self-care and usual activities status was positive and significant in univariate tests.

This is in agreement with the Ho and Hocaoglu (2011)23 study, which assessed the phases and the stages of HD from patients (ages between 30-89 years old), and found that as the stages of the disease progressed, the symptoms of the disease became more noticeable. In particular, in the last stage of the disease (older patients), the issues raised were physical or functional (i.e. difficulties with ambulation, swallowing, sleeping, speaking, writing and dressing). Generally, as the individual aged and the disease progressed, the symptoms of the disease became more evident and this has as an impact on Health Status and the QoL of the patient. This can be seen in our findings also, as the EQ-vas scale analysis and the Cumulative QoL score analysis showed significant associations between the current age of the patients, indicating that both QoL and overall health status deteriorates with age.

There was no association between the current age of the patients and the presence of psychological problems. This indicates that psychological issues in HD are independent from the age of the patient. This also has an intuitive explanation, as even in pre-symptomatic stages (i.e. patients who are younger than 40 years old, excluding juvenile cases) patients can feel stress for the extent of the detrimental effects of the disease33.

However, multivariate models suggested that current age might not be an independent predictor of QoL but its effect on QoL might instead be a reflection of disease duration, as discussed further down.

Disease status (symptomatic and asymptomatic)

The study determined that there was a significant statistical association between most categories of the EQ-5D Descriptive System and disease status. However, for ‘pain/discomfort’ and ‘anxiety/depression’, the difference in status between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients was not significant.

As discussed above, it is possible that Cypriot patients perceived the word ‘discomfort’ to point to both mental and physical discomfort, therefore the result shows that even asymptomatic gene carriers had a psychological alteration, although they had not yet experienced any symptoms of the disease. Generally, pre-symptomatic HD patients participating in other HD studies had psychosocial QoL issues relevant to this subgroup as well, whereas physical, functional and cognitive issues hardly featured in HD gene carriers33,34.

Overall, in the EQ-vas scale and the Cumulative QoL score, asymptomatic patients reported better QoL and better Health Status, respectively, in contrast to symptomatic patients, and the differences in these scores was statistically significant.

Parent-of-origin (paternal and maternal)

The sample of the study comprised of more patients who had inherited HD maternally, rather than paternally. However, the parent-of-origin was not found to be a statistically significant factor in determining the extent of the problems considered in the EQ-5D descriptive system. We are not aware of any studies considering the association of the parent-of-origin transmission and the QoL of HD patients. From our results, one can postulate that the parent-of-origin is not associated with the QoL of the patients, but further research on a larger sample size of HD patients is required, in order to confirm this finding.

Age at onset and Age tested

Age at onset was another determinant considered, and the results show that of the patients reporting severe problems in the 5 EQ-5D Descriptive System categories, the majority had an age at onset above 40 years old. The same trend was evident for patients reporting a cumulative QoL above median. However, statistical associations between age at onset and the determinants of the EQ-5D Descriptive System (with the exception of self-care) and the EQ-vas scale were not found to be significant in multivariate analyses.

Interestingly, patients who had reported severe problems in the majority of the EQ-5D Descriptive, were younger at onset than patients who had reported moderate problems, reflecting the association between number of repeats of the mutant allele, earlier age at onset and worse disease progression. Therefore, the unexpected positive association between age of onset and reporting moderate or severe problems in the 5 EQ-5D Descriptive System categories or reporting a higher cumulative QoL is most likely driven by the larger number of patients with a higher age-of-onset that reported “Some Problems”.

In contrast to age at onset, age tested was a significant determinant of mobility and self-care scale scores. However, similar to the results considering the age at onset of the disease, patients reporting severe problems in the mobility, self- care and usual activities status of the EQ-5D Descriptive System were generally over 40 years old and patients tested between the ages of 40-48 years old, reported severe problems, whereas patients tested when they were over 49 old years reported moderate problems, a difference which was statistically significant. These results are in agreement with another large study, which found that the rate of HD progression was more rapid with younger age at onset, in particular with issues such as motor impairment (dystonia) and the rate of cognitive and functional progression32.

When both variables were entered in multivariate regression models, age tested did not retain its significance, and instead, age at onset was positively and significantly associated with self-care problems compared to no problems. This indicates that of the two ages, age at onset is most influential in determining quality of life.

Disease Duration (years since onset)

Years since onset was used in univariate and multivariate analyses as an indication of disease duration. Even though disease duration was not significantly independently associated with the five EQ-5D scales, in multivariate analyses in symptomatic patients, correcting for age at onset and age tested, disease duration was significantly and positively associated with worsening problems in mobility, self-care and usual activities. This makes disease duration perhaps the most influential predictor of QoL, after accounting for all other demographic and clinical characteristics. This was also evident in multivariate analyses on the cumulative QoL where years since onset was the only significant predictor.

In related research, patients with either juvenile onset of disease or late onset of symptoms had significantly shorter disease duration than those who had onset in mid-life (onset 20-49). The course of HD is probably shorter in the older onset of HD, due to other unrelated conditions which can shorten life expectancy35. These findings might explain why disease duration was significantly associated with QoL only after adjusting for age at onset.

Surprisingly, the impact of disease-duration was not evident in multivariate analyses on the cumulative QoL where, instead, age at onset was the only significant predictor. Larger subject numbers are needed to delineate the interaction between age of onset and disease duration on the QoL and fully explain these findings.

Number of repeats in HD allele

For patients who reported severe problems, the number of repeats in their mutant HD allele usually exceeded 45 repetitions. More specifically, the correlation between the number of repeats and the severity of issues in mobility, the self-care and pain or discomfort status was positive, despite being non-significant with the exception of the self-care scale.

These results are in agreement with a larger related study considering the association of the number of CAG repeats and the clinical progression of more than 500 HD patients31. The result in that study was that the number of repeats was a small but significant predictor of progression rates of HD (measured using neurological signs, motor impairment, cognition and daily function).

Strengths and Limitations

This study assessed, for the first time, the QoL of HD patients in Cyprus and aimed to identify some of the major factors affecting QoL. This study can be regarded as the first step in an approach to improving living conditions among these patients, with informed and targeted health promotion programmes. The study invited all alive patients with Huntington’s disease who were physically and cognitively able to consent to and participate in the study. In addition, all demographic and clinical characteristics were extracted from patient files, instead of obtained through self-report, minimizing information bias.

Despite the strengths of the study described above, it also had some limitations. First, the sample size of the study was too small. Of the Cypriot registered HD patients, only the 42.6 % took part, while the remaining 57.4% did not participate for several reasons. Some were either too severely disabled to come to CING or be contacted for completion of the questionnaire, or because their treating physicians suggested that particular patients had refused contact from CING previously. Not considering these patients is a limitation, because the study may not be capturing the true extent of the issues considered for HD patients, since the most severely affected patients were not part of the study. This is particularly true following the exclusion of the small number of carer/proxy reports for the cognitively impaired, advanced-stage HD patients. Of the other patients, some were unable to attend, due to personal reasons, such as professional obligations or because they were living in a ward.

Secondly, some patients had reported overly positive health states, which may have been related to some mental impairment. A mini mental state of examination was required since it is a reliable method to assess the cognitive disability of the patients and is commonly uses in neurological studies, including HD30,31.

Finally, the Greek translation of the questionnaire may not have been the most accurate in carrying across the meaning of some words. For example, the word ‘discomfort’ in Greek points not only to the physical domain (such pain), but also to the mental domain. This was confusing for the Cypriot patients.

Future work

A first extension of this work would be to further the investigation in order to assess the QoL of the remaining Cypriot patients, who did not have the opportunity or the capacity to take part. Obtaining evidence from the entire Cypriot patient population is important so that we can characterise definitively the aspects affecting QoL. Further work in HD would necessarily include a short mental test prior to the completion of questionnaires, to determine whether the patient can accurately self-assess their physical mental state.

In addition, the study used a generic questionnaire assessing the QoL of HD patients. Once the HD specific questionnaire is approved and a Greek translation is available, it would be useful to see how the new questionnaire could add to the pool of evidence regarding HD. HD is a multi-faceted disease, and the additional considerations of an HD-specific questionnaire will be useful in this aspect.

Conclusions

The study assessed, for the first time, the QoL of HD patients in Cyprus and demonstrated that QoL in the Cypriot HD patient population was moderately to severely affected by the disease. The disease was most frequently found to affect the ability of Cypriot patients to carry out their usual, day-to-day activities and to care for themselves. The psychological state was found to play a crucial role in the QoL of HD patients, since the majority of the patients, including pre-symptomatic ones, reported moderate anxiety and depression. In terms of the physical domain, a large number of HD patients reported moderate problems in their mobility status. The study did not identify pain as being a symptom in the tested population, although discomfort was prevalent. The overall Health Status of the patients was defined as average to poor, whereas the Cumulative QoL score indicated moderate issues with QoL. Disease duration was evidenced as perhaps the most important determinant of QoL, after accounting for all relevant demographic and clinical characteristics, including disease status.

The results of this study could potentially be utilized for improving the quality of management of HD in Cyprus, in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. They can be utilized by clinics and patient support groups in order to better support, empower and care for HD patients and their families.

Data Availability Statement

The authors provide detailed data regarding quality of life responses in Tables 3-7. All statistics were derived from information in these tables. Unfortunately, more detailed information and specific subject characteristics cannot be made publicly available due to ethical restrictions from the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee. For further information regarding data availability please contact [email protected].

Competing Interests

The authors have no financial or non-financial competing interests to declare.

Corresponding Authors

Eleni Zamba-Papanicolaou ([email protected]) and Christiana A. Demetriou ([email protected])

Methods: We investigated whether anthocyanin antioxidants added daily to the drinking water could affect CAG repeat instability in several organs and behaviour in R6/1 HD mice. In addition, anthocyanin-treated and untreated R6/1 HD mice at 22 weeks of age were tested in the open field test and on the rotarod.

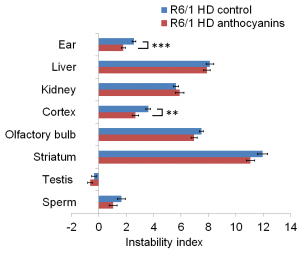

Results: Anthocyanin-treated R6/1 HD mice showed reduced instability index in the ears and in the cortex compared to untreated R6/1 mice, and no difference in liver and kidney. There were no significant differences in any of the parameters tested in the behavioural tests among anthocyanin-treated and untreated R6/1 HD mice.

Conclusions: Our results indicate that continuous anthocyanin-treatment may have modest effects on CAG repeat instability in the ears and the cortex of R6/1 mice. More studies are required to investigate if anthocyanin-treatment could affect behaviour earlier in the disease course.

]]>Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder caused by a CAG expansion in exon 1 of the Huntingtin (HTT) gene encoding the polyglutamine protein HTT 1. There is an inverse relationship between CAG repeat length and age of onset 2. Mouse Htt is ubiquitously expressed and the function of the normal protein is still under extensive investigation, although it is known to interact with trafficking motors and clathrin-interacting protein 3. A selective pattern of neuropathology exist in HD, with loss of neurons that is most severe in the caudate and putamen 1. However, the mechanisms underlying this selective neurodegeneration remain poorly understood. Somatic CAG length expansion is correlated with neuropathology and probably precedes the onset of symptoms 4. The R6/1 transgenic mouse is a widely used HD model containing the human HTT N-terminal fragment containing exon 1 with expanded CAG repeats 5. We have recently shown that the striatum and the cortex in R6/1 mice display a dramatic and periodic expansion that is mechanistically different from the slow expansion observed in most other somatic tissues 6. Stoichiometries of base excision repair (BER) proteins correlates with the degree of somatic instability seen in the striatum and cerebellum of HD transgenic mice 7. Similarly, age-dependent CAG repeat expansion are reduced in R6/1 mice lacking the BER enzyme 7,8-dihydroxy-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG)-DNA glycosylase (Ogg1) 8. Also, the BER DNA glycosylase Nei-like 1 (Neil1) has recently been shown to be a genetic modifier of both somatic and germline CAG repeat instability in R6/1 mice 9. Deletion of the mismatch repair proteins Msh2 and Msh3 has been shown to abolish somatic expansion in several HD mouse models 10,11,12. Recently, the mismatch repair genes Mlh1 and Mlh3 have also been shown to modify CAG instability in HD mice 13.

It has been proposed that oxidative damage plays a role in the progression of several neurodegenerative diseases 14. Reactive oxygen species are generated as by-products of mitochondrially catalysed reactions of the electron transport chain or cellular inflammation. Mice with expanded polyglutamine have shown Htt on neuronal mitochondrial membranes 15 with elevated levels of 7,8-dihydroxy-8-oxoguanine and lipid peroxidation 16, and mitochondrial dysfunction 17. It has been shown that the presence of aggregated mutant Htt fragments directly causes free radical production 18.

Several anthocyanins and their aglycones have shown strong antioxidant activity 14,19. Anthocyans are flavonols, which occur ubiquitously in the plant kingdom and confer bright red or blue colouration on berries and other fruits and vegetables. Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) and bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) – which is very similar to blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) – are rich in several anthocyanins. Anthocyanins can be metabolised in the intestine and enter the bloodstream to peripheral tissues (reviewed by 20,21). Anthocyanins from dietary blueberry has been detected in several brain regions, including cerebellum, cortex, hippocampus and striatum of rats 22,23, and cerebellum, cortex, midbrain and diencephalon in pigs 24. Blueberry anthocyanins have been shown to enhance cognitive and motor behaviour in aged rodents 22,23,25,26,27,28,29. Wild blueberry juice also improved paired associate learning and word list recall in older human adults with early memory changes 30. Blueberry extract also reduced oxidative DNA damage in mouse brain tissue in vitro as evaluated by the comet assay 26.

At present, there are no curative therapies available for HD. R6/1 HD mice have reduced motor coordination and cognitive deficits 31,32,33.Several antioxidants have been tested on animal models of HD, for instance a combination of coenzyme Q10 and remicade hydrochloride 34, alpha-lipoic acid 35, BN82451 36, resveratrol 37, fisetin 38, and N-Acetylcysteine 39, and have shown varying effects on survival, weight loss and rotarod performance.

We investigated whether anthocyanin antioxidants could reduce CAG repeat expansion and improve behavioural performance in the R6/1 mice. R6/1 HD mice were given Medox®, containing a combination of anthocyanins derived from bilberry and blackcurrant, in their drinking water from 4 weeks of age until they were sacrificed at 22 weeks of age. Several organs including male gonads and brain tissues were harvested to examine whether anthocyanins could reduce CAG repeat expansion in R6/1 mice. Before termination of the experiment, the exploratory behaviour of the mice was investigated in the open field, and balance and coordination was tested on an accelerating rod (rotarod test).

Results

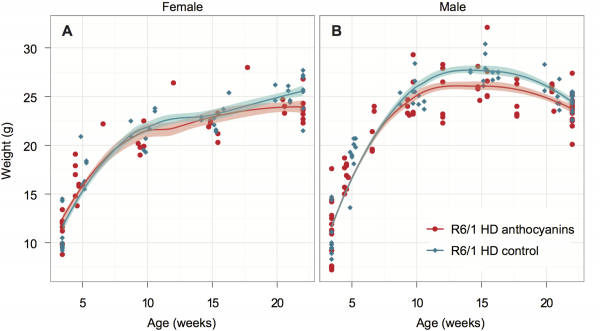

The effect of anthocyanins on body weight of R6/1 HD mice

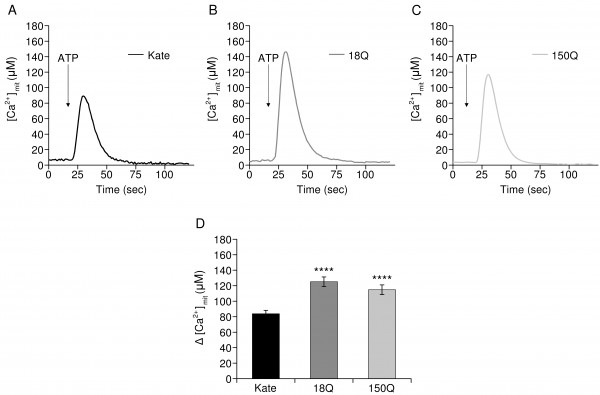

All mice were weighed regularly to check their health throughout the experiment. The growth curves for female and male anthocyanin-treated and untreated R6/1 HD mice are shown in Fig. 1. The growth rate of female and male R6/1 HD mice is indistinguishable between anthocyanin-treated and untreated mice up to 10 weeks of age.

The R6/1 HD mice were grouped by gender and shown with Loess smoothed curves and a 95% confidence interval for each smoothing (shaded bands around lines). Each mouse was weighted 5-6 times. Untreated R6/1 HD control mice n = 20, 11 males and 9 females; anthocyanin-treated R6/1 HD mice n = 23, 15 males and 8 females.

Fig. 1: Growth curves for anthocyanin-treated and untreated R6/1 HD mice.

Female R6/1 HD mice continue to gain weight throughout the experiment regardless of treatment. However, the growth curves for anthocyanin-treated and untreated R6/1 HD female mice diverge at around 20 weeks of age. As indicated by the 95 % confidence interval around the growth curves in Fig. 1A, anthocyanin-treated female R6/1 HD mice gained significantly less weight than female R6/1 HD untreated mice after this point.

For anthocyanin-treated and untreated R6/1 HD male mice the growth curves begin to diverge at around 11 weeks of age. As indicated by the 95 % confidence interval around the growth curves in Fig. 1B, anthocyanin-treated R6/1 HD male mice were significantly lighter than untreated R6/1 HD male mice up to 21 weeks of age. Notice that both treated and untreated male R6/1 HD mice lost weight from about 14 weeks of age, which is a genotype effect 34,39,40. It appeared that the anthocyanin-treated male R6/1 HD mice maintained their body weight better than untreated R6/1 male mice from about 16 to 22 weeks of age. In contrast, no weight loss was observed in anthocyanin-treated and untreated R6/1 HD female mice.

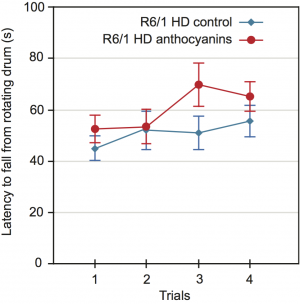

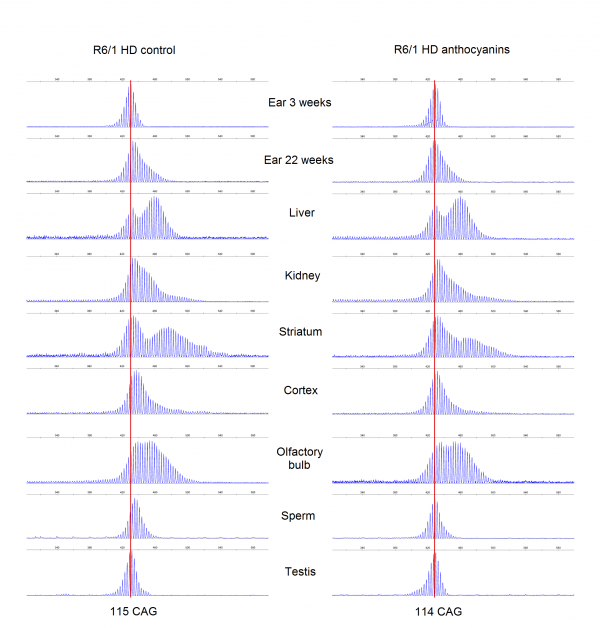

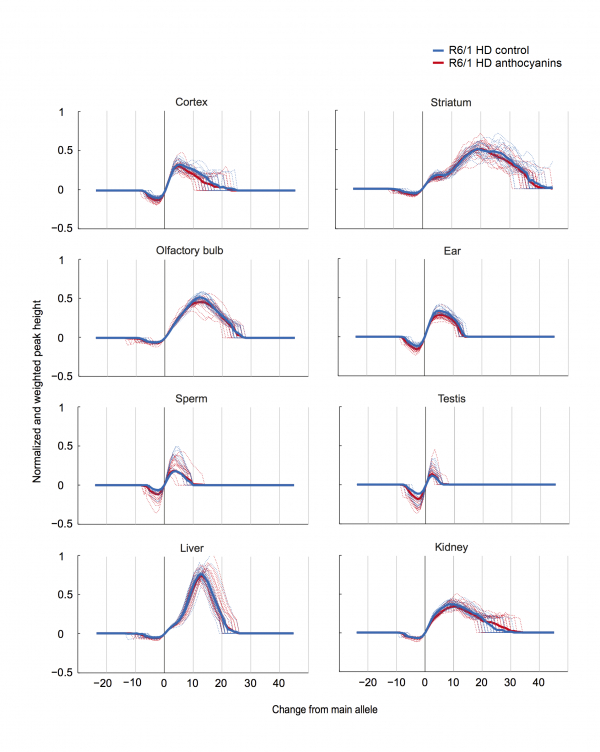

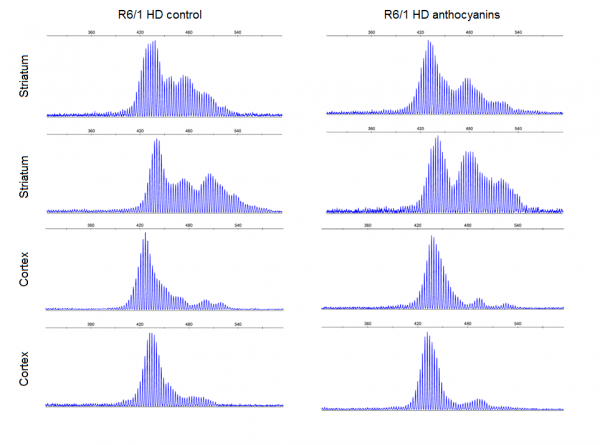

CAG repeat expansion in R6/1 mice