The Pokémon Go craze and its implications for public health

Pokémon Go is a game premised on interactions between the real world and a virtual Pokémon world via an application on the user’s mobile phone. The objective of the game is to catch 151 different Pokémon characters, which can be found at various publicly accessible real-world locations, such as parks, businesses, bodies of water, and numerous other locations in between1. As of July 11, 2016, 5.9% of all Android users in the United States, or about 6.4 million people, had not only downloaded Pokémon Go but played it daily since its release on July 6, 20162,3. Since the end of August, the number of Pokémon Go daily users has diminished as interest in the game has waned, daylight hours have reduced, and weather conditions have become less conducive to spending time outdoors4. Despite waning interest, one clear outcome of the Pokémon Go phenomenon in summer 2016 was that millions of people spent more time outdoors – traveling farther and wider to “catch ‘em all” – than they might have otherwise. Another is that there were large groups congregating together at “hot spots” of relevance to the game, creating anomalous concentrations of people that ordinarily would not occur. Although the initial Pokémon Go fad may have reached its conclusion, it and other games in the new augmented reality genre could induce similar changes in human behavior in future summers.

There are many benefits of spending more time outdoors, including higher levels of physical activity with associated positive health outcomes such as reduced rates of obesity and depression5,6,7. Pokémon Go players undoubtedly enjoy many benefits of playing this game and spending more time outdoors, but at the same time there have been numerous reports of risks to personal health and safety associated with playing Pokémon Go, including armed robbery, traffic collisions, and various other accidents as extreme as walking off a 90-foot cliff8,9,10. Here, we draw attention to another possible risk of playing Pokémon Go: increased exposure to mosquito bites and to the pathogens that they transmit in certain areas and at certain times of year. Although Pokémon Go has yet to be released in some countries with the greatest risk of mosquito-borne pathogens, the timing of its release occurred just as the continental U.S. was entering a seasonally high period of increased risk for transmission and/or introduction of mosquito-borne pathogens11,12,13.

The when, where, and who of mosquito-borne pathogen transmission

A number of mosquito-borne pathogens, especially viruses, pose a recurring seasonal risk to individuals who spend more time outdoors in summer months in the continental U.S. These include West Nile virus (WNV), Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), and La Crosse virus (LACV), all of which are maintained in enzootic cycles involving multiple non-human vertebrate and mosquito species. Because humans are dead-end hosts for transmission of these viruses14,15,16, transmission to humans ultimately results from infections among non-human vertebrates on which various mosquito species regularly engage in blood-feeding11. Outdoor activity near key habitats for those species may elevate the risk of exposure to these viruses17,18,19,20.

The timing of outdoor activity is also important, as different vector species tend to bite at different times of day, with the vector of LACV biting during the day21, vectors of WNV and SLEV generally biting in the hours around and after dusk22,23,24, and the multiple vectors of EEEV biting at a variety of times. Outdoor activity by humans at these times has been documented as a risk factor for both WNV25 and LACV20 infections. Tweets from mobile devices using the case-insensitive string “#pokemongo” also appear to occur most frequently in the hours before and around dusk (Fig. 1). Although some portion of these tweets are likely composed indoors, it is also likely that many of these tweets are composed outdoors as players interact with each other. Much like mobile phone records and other digital data, twitter activity can serve as a proxy of time allocation in different areas26. To the extent that tweets from mobile devices in Fig. 1 serve as a proxy for time spent outdoors, it appears that there may be elevated Pokémon Go activity around the time that many people take lunch breaks and in the hours after work but before dusk. Some outdoor activity may continue around dusk and shortly after, but then drop to its lowest levels during late night and early morning hours (Fig. 1).

Number of tweets from mobile devices by hour relative to the daily maximum in Miami, Florida (summed over July 17-24, 2016) with the gray line representing tweets mentioning “RT” (a commonly used string indicating a re-tweet) and the black line representing tweets mentioning “#pokemongo.” The shaded areas provide a crude indication of heightened times of biting activity for Ae. albopictus and aegypti (blue), Cx. tarsalis, quinquefasciatus, and pipiens (red), or both (purple)23,24,27,28,29. Tweets were downloaded using the Perl library Net::Twitter30, and all code that was used to make this figure is https://github.com/confunguido/PokemonDataAnalysis.

Fig. 1: Timing of mosquito biting and #pokemongo tweets

With the potential for increased contact between humans and certain mosquito vectors also comes an increased risk of sporadic transmission of non-endemic tropical diseases in the continental U.S., including dengue (DENV), chikungunya (CHIKV), and Zika (ZIKV) viruses. Within the last several years, there have been short chains of local transmission of DENV, CHIKV, and most recently ZIKV in the continental U.S., with autochthonous, mosquito-borne transmission of ZIKV documented recently in several neighborhoods in Miami, Florida31,32,33. Mathematical models suggest that a key factor in the size of these transmission chains and the risk to individuals is the rate of contact between people and mosquitoes34,35. Aedes species (Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus) transmit these viruses12,36 and bite during a broad range of times throughout the day, but especially in the hours before dusk28,29. Given the relatively catholic blood-feeding preferences of Ae. albopictus, exposure to biting by these mosquitoes depends on the relative abundance of non-human vertebrate host species within an area29,37,38.

Pokémon Go activity is often concentrated consistently over time around specific locations known as PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms1 (Fig. 2). PokéStops are locations that players visit to collect necessary items that aid in collecting more Pokémon, and are generally located in public outdoor spaces, such as art installations, monuments, and parks139. Pokémon Gyms are outdoor locations that players visit to train their Pokémon and to interactively battle one another, spending prolonged periods of time outside around other players40. The extent to which PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms overlap with areas where Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus are actively engaged in blood feeding is likely to vary considerably, with locations near parks or residential areas generally having the highest possibility of overlap. In such locations, one relevant possibility is that human congregation around these locations could allow for a shift towards more frequent biting on humans and potentially longer transmission chains of pathogens transmitted by these mosquitoes.

A group of Pokémon Go players congregate to catch Pokémon. Congregation such as this is an inevitable aspect of playing the game. Pokémon are more likely to appear near PokeStops, and players frequent Pokémon Gyms to engage in interactive play with others1. (Photo credit: Mauna Dasari)

Fig. 2: Outdoor congregation of Pokémon Go players

Given recent transmission of ZIKV in the Miami area, we examined the extent of spatial overlap between PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms (obtained from https://mapokemon.com) and portions of the city where mosquito-borne transmission of ZIKV has been documented (Fig. 3). We found at least two such locations at the edges of one of these neighborhoods, several more within one mile, and dozens more within the Miami area as a whole. Overlaying a map of Ae. aegypti occurrence probabilities onto these locations, we found that the probability that Ae. aegypti occur in the general vicinity of these areas ranges 0.92-0.9636. Although this analysis provides no evidence of a role of Pokémon Go activity in the Zika outbreak in Miami, it does highlight the potential for spatial overlap between areas of Pokémon Go activity and mosquito-borne virus transmission. Furthermore, because the occurrence probability maps that we used are intended primarily for comparative purposes at broad geographic scales rather than for associative studies at the finer scales at which Pokémon Go activity takes place, the juxtaposition of these occurrence probabilities with PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms serves only as a general reminder of the presence of Ae. aegypti throughout the area. Just like anyone else spending time outdoors in these areas, individuals playing Pokémon Go should heed cautions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for reducing exposure to ZIKV and other viruses in the context of an active outbreak. At the same time, it is worth bearing in mind that risk of exposure to ZIKV or other viruses around the vast majority of PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms will usually be negligible. In those cases, the risk of exposure to one of these viruses should generally not outweigh the health benefits of increased time outdoors that is associated with playing Pokémon Go41,42.

Google Maps satellite image of Miami, Florida. The area of each red dot shows the probability of occurrence of Ae. aegypti within the 5 km x 5 km grid cell in which a given PokéStop or Pokémon Gym has been geo-located by https://mapokemon.com. These probabilities do not necessarily correspond to probabilities that Ae. aegypti occur specifically at PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms, or that they engage in contact with individuals playing Pokémon Go. Instead, they serve as a reminder of the uniformly high probability across the Miami area that Ae. aegypti are generally present. The regions outlined in blue demarcate neighborhoods in Miami-Dade County, FL that had experienced local ZIKV transmission as of October 31, 201633. Map was created with RgoogleMaps43. PokéStop and Pokémon Gym location data provided by Alexander Wigmore from https://mapokemon.com.

Fig. 3: PokéStops and Pokémon Gyms in Miami

Even if spending more time outdoors playing Pokémon Go could result in higher exposure to mosquito-borne viruses, this may not necessarily result in higher incidence of overt disease associated with mosquito-borne virus infection. Many infections of humans by these viruses are asymptomatic, and those that are not tend to occur with higher probability in particular age groups. Specifically, LACV infection poses a greater risk of neuroinvasive disease to children, and WNV infection poses a greater risk of neuroinvasive disease to older adults44. Approximately 9 out of 10 Pokémon Go players are below age 55 and nearly 7 out of 10 are below age 3545, suggesting that Pokémon Go players who become infected with WNV may generally be at relatively low risk of experiencing neuroinvasive disease. SLEV and EEEV infections pose a more even risk of neuroinvasive disease with respect to age, although their absolute risk is very low44. For DENV, CHIKV, and ZIKV, the risk of disease by age depends on the history of transmission and the extent of immunity within a population. Because there is virtually no immunity to these viruses in the U.S., any autochthonous transmission that happens could result in symptomatic disease in individuals of any age. Direct associations between playing Pokémon Go and acquiring these diseases have not yet been formally investigated, however.

Having fun, staying safe, and leveraging novel data streams for public health

We have drawn attention to persistent and emerging mosquito-borne disease risks in the continental U.S. and have noted their association with time spent outdoors25,46. Although increased time outdoors playing Pokémon Go could elevate the risk of acquiring these diseases, it is important to note that the risk of acquiring these diseases within the continental U.S. is extremely low in an absolute sense and that Pokémon Go activity is not expected to ever become a major driver of transmission relative to other factors31,44. Nonetheless, it is important for Pokémon Go enthusiasts and others who spend time outdoors in areas and at times of heightened mosquito biting to be aware of these risks and to take proper precautions per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines47, including wearing long sleeves and pants when possible and applying insect repellents with DEET or another recommended active ingredient. Surveys conducted in the continental U.S. suggest that there is a need for improved education around these issues48.

In addition to personal protection, there may be actions that the developers of Pokémon Go and similar games could consider in partnership with health authorities to help mitigate these risks. For example, in-app alerts could be used to notify players of local, seasonally relevant mosquito-borne disease risks, or to remind players to apply insect repellent. In some cases, it may also be advisable for Pokémon Gyms or PokéStops to be relocated if a specific risk emerges, such as the ZIKV outbreak in Miami or in the event mosquitoes test positive for a virus such as WNV. Although Pokémon Go activity has peaked for now49, these considerations remain relevant for those who will play this and future offerings in the augmented reality space in coming summers.

As Pokémon Go encourages people to spend more time outdoors actively using their mobile phones, at times in large groups, unique research opportunities may also emerge. A wide variety of novel data streams are increasingly applied to address public health challenges50,51, such as the use of Twitter data to model influenza dynamics52. Similarly, geo-referenced, time-stamped data about Pokémon Go activity could provide a rich data source on spatial and temporal patterns of indoor and outdoor time use. To the extent that associations might exist between congregations of Pokémon Go players and mosquito-borne disease risk, future work could address the extent to which other outdoor congregations at times of high mosquito biting activity, such as outdoor movies and barbecues, might pose an elevated risk of exposure to mosquito-borne diseases. In conclusion, as millions of people continue to explore augmented reality games such as Pokémon Go each day, it will be important for public health officials and others to think creatively about how to minimize risks and maximize opportunities associated with this fundamentally new and distinct activity.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Ethics Statement

The individuals in this manuscript have given written informed consent (as outlined in PLOS consent form) to publish these case details.

Corresponding Author

Rachel Oidtman, E-mail: [email protected]

Alex Perkins, E-mail: [email protected]

Data Availability Statement

Data provided by: https://mapokemon.com from Alexander Wigmore

Unintended pregnancies in Brazil – A challenge for the recommendation to delay pregnancy due to Zika

The World Health Organization has recently declared the emerging Zika virus an international public health emergency1. The virus, which reached Brazil to cause a major epidemic starting in April 2015, has rapidly spread to over 28 countries2 and may still reach many more considering the widespread distribution of its vector species (Aedes aegypti mosquitoes) and the high transmission rates observed so far. Concerns also involve the possibility of a second vector of Zika transmission, Aedes albopictus, which is currently expanding its ecological niche globally 3,4 .

However, the biggest concern about the Zika outbreak is the potential link with the surge of reported cases of microcephaly and other malformations of the central nervous system in newborns from mothers infected with the virus during pregnancy1. The proposed link between Zika infection and congenital microcephaly is not conclusive1,5, but given the long-term consequences of this birth defect (which can range from mild developmental delays to severe, lifelong motor and cognitive impairment), a number of Officials in Latin America have recommended that women avoid or defer pregnancy, giving time for the epidemic to subside and therapies to develop6. Among these were representatives of the Health Ministries of Ecuador, Colombia, Jamaica and El Salvador. In Brazil the recommendation to postpone pregnancy has not been made official, yet the director of the Surveillance Department at the Ministry of Health – Cláudio Maierovitch – has stated that women from high-risk areas who can wait to conceive should do so2.

The implementation of such a recommendation requires, however, that women in these areas are not only clearly informed about the risks posed by infection, but also have control over their reproductive choices. There are few reasons to doubt that most women will be aware and informed about the disease and its consequences through the widespread media. Yet ensuring control over the timing of pregnancy is a more daunting challenge, especially considering that many babies are born out of unplanned pregnancies – even when strong motives for avoiding them exist (e.g. age, economic, social, professional and health-related).

In Brazil, the country most affected by the Zika outbreak so far, data from a demographic survey from 2006 indicate that approximately half of all births that happened five years prior to the survey were unplanned7. A demographic group at particularly high risk is that of adolescents (defined as the period from ten to 19 years old, following the World Health Organization definition8). Pregnancies in adolescent girls are far more likely to be unplanned because this group often lacks access to contraception and family planning methods, or the knowledge to use them appropriately. In such circumstances, the risk of conceiving a child with congenital anomalies might not affect the likelihood of a pregnancy.

To gauge the magnitude of the barriers preventing the postponement of parenthood in Brazil, we evaluated pregnancy rates in adolescent groups, and their spatial heterogeneity in the country, in recent years for which data are available (2012-2014). Data on live births were obtained from the Information System on Live Births (SINASC9). Population estimates for each state and age group were obtained from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics10 and annual population data were calculated by spline interpolation of census data. Analyses were conducted using the freely available analytical software Epipoi11.

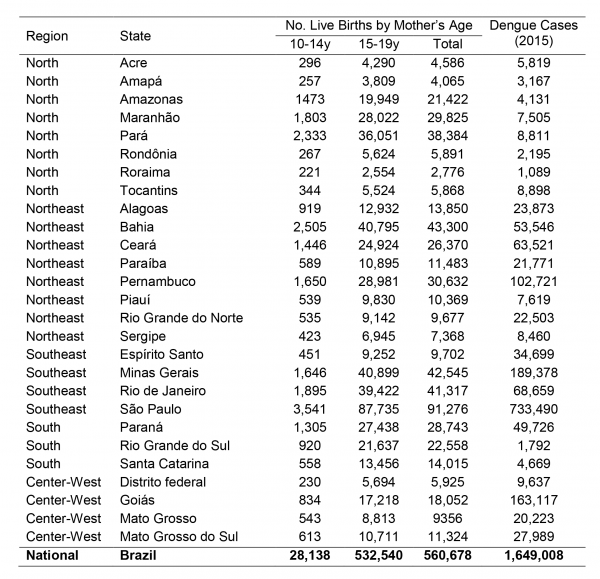

Although Brazil has experienced a substantial decline in fertility rate and a corresponding displacement of reproduction towards older ages over the last decades, nearly 20% of children born in Brazil today are by teenage mothers, a proportion nearly twice as high as the world average (11%) in this age group12. Every year, over 560,000 children are born to adolescent mothers in Brazil (Fig.1).

Fig. 1: Mean number of live births per year (2012-2014) from adolescent mothers in each Brazilian state (source: Datasus: SINASC) and number of dengue cases in 2015 (source: SVS, Brazlian Ministry of Health).

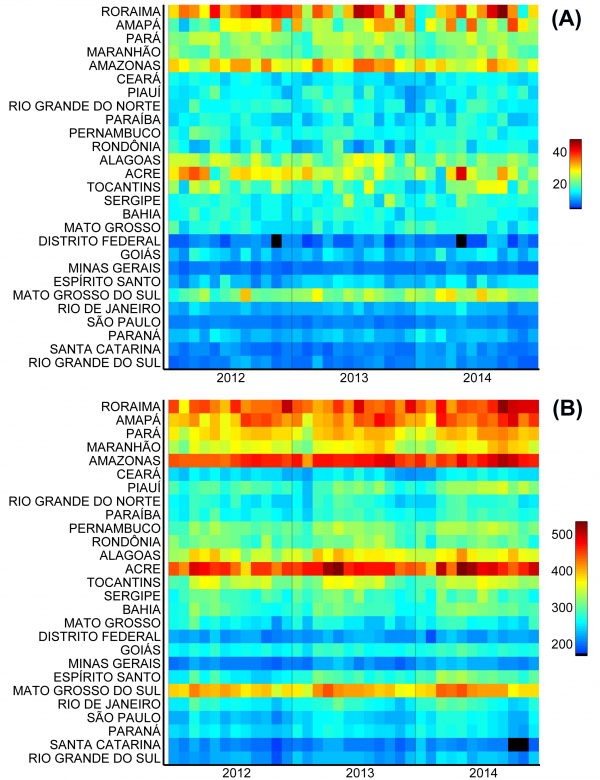

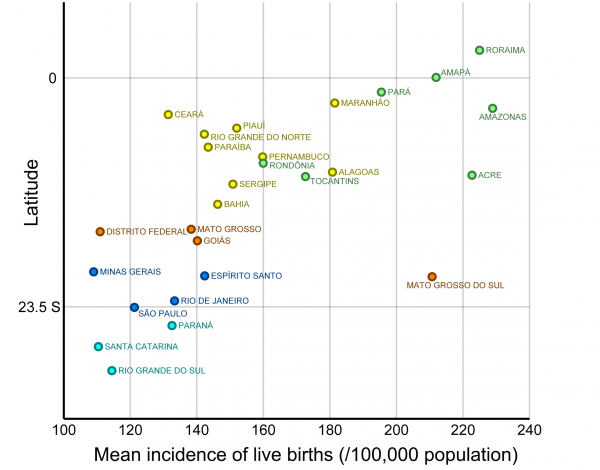

The states with the highest incidence of births from adolescents in Brazil are those in the northern region (coinciding with a large part of the Amazon area) and Mato Grosso do Sul (Fig.2). The pattern is similar for mothers aged 10-14 years (Fig.2a) and 15-19 years (Fig.2b). When birth incidence among adolescent mothers (10-19y) is plotted against latitude (Fig.3), it is clear that it increases with decreasing latitudes, being far higher in the tropical northern states. In absolute terms, however, most births occur in the most populous southeastern states, most notably São Paulo (Fig.1). The distribution of dengue cases in 2015 by state is shown in Figure 1, as an indicator of those states with climatological and sociodemographic suitable conditions for the circulation of Aedes mosquitoes. As shown in Fig.1, the highest number of dengue cases also occur in populous states in the southeast (predominantly São Paulo), matching to a large extent the spatial distribution of the absolute number of births from adolescent mothers.

Fig. 2: Monthly incidence of live births (per 100,000 age-specific population) from mothers aged (A) 10-14 years and (B) 15-19 years in each Brazilian state.

Fig. 3: Average incidence of live births (per 100,000 age-specific population; 2012-2014) from mothers aged 10-19 years in each Brazilian state by the latitude of the state’s capital

The pre-existing high incidence of what are most likely unplanned births by adolescent mothers in high-risk areas emphasizes that the recommendation to delay pregnancy during the current crisis is only a partial solution to protect babies from the putative effects of infection. Unless accompanied by changes in the accessibility to contraception methods and a drastic change in health education, access to and attitudes towards family planning, the recommendation to delay pregnancy will leave over half a million pregnant adolescents vulnerable every year until effective interventions (including vaccines) to prevent Zika infection are not available13.

More complicated yet is the communication of risk at a time when microcephaly has not been firmly linked to Zika infection. While we await the final verdict of the magnitude of risk and strength of association, recommendations related to conception in the time of Zika should be approached with care, health education and real access to prevention.

Competing Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Commentary

Recent publications describe barriers faced by medical trainees in volunteering for the Ebola outbreak in West Africa1. Concerns include fear of contracting and importing the disease, violating residency requirements, scheduling conflicts, family obligations, and lack of experience and maturity. There was a theme of doubt over whether the effort and risks justified benefits to the trainee and the overall outbreak response. We describe the successful four-week deployment to Liberia of a first year infectious diseases trainee via the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) of the World Health Organisation (WHO), which received prospective approval from the residency supervisory committees and employing hospital management.

International electives, despite being widely recognized for their theoretical benefits in residency training, are often entwined with problems in practice2. Training bodies must reconcile accreditation requirements with unique educational opportunities and ensure that the quality of training is not limited by poor supervision and demands to practice outside one’s competencies. Employers who fund trainees need to justify the expense with little direct return. There are logistic and safety issues for which someone must assume responsibility. An elective in a massive outbreak such as that in West Africa exacerbated all these concerns. Once overcome, however, the benefits would be arguably all the greater.

A Singapore team consisting of an infectious disease physician and an infection prevention and control expert had been deployed through GOARN to Liberia twice in 2014. The possibility of including a fellow with an interest in this type of work in a third deployment was raised. A program was designed with components mirroring an on-site posting.

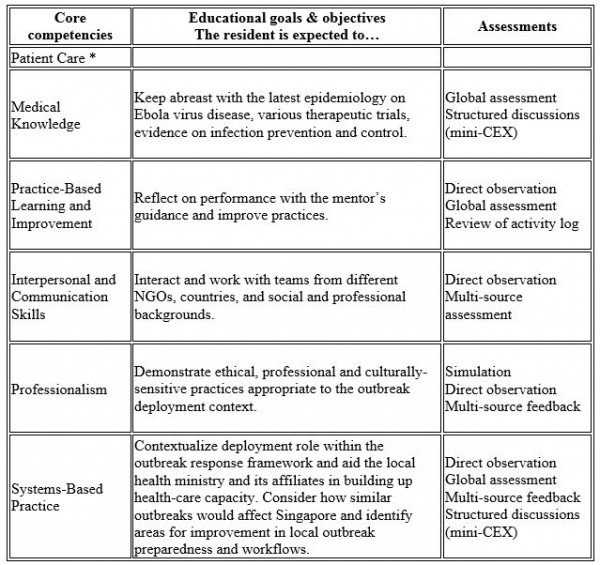

Post-graduate medical education in Singapore gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-International (ACGME-I) in 2010. Hence, the learning objectives (Fig. 1), supervisory framework and assessment methods of the program aligned closely with the ACGME core competencies. Formal pre-deployment training consisted of a specific course in Darwin in December 2014, co-organised by GOARN and RedR, Australia. In addition, specific prerequisites were met including the UN-mandated online safety course and health requirements.

Concurrently, an application proposal was submitted to the national residency training committees and the sponsoring institution. This brought about concerns similar to those previously cited: safety, residency requirements, and the value of learning, especially during the first year of training. With justifications the elective received approval. Deployment costs of the posting were met by GOARN while the wage was maintained locally.

In February 2015, the Singapore team of three joined the Liberian infection prevention and control efforts in Monrovia. A ‘ring fencing’ infection control approach was being introduced, including enhancement of triage, training and providing supplies in high priority health-care facilities in the capital city and at the nation’s borders3. The fellow produced an electronic database that enabled monitoring infection control standards in the health facilities. This aided the Liberian Ministry of Health in prioritizing resources and united efforts from the various NGOs to improve efficiency and accountability. During this period, there were close working relationships with the many partners also assisting in the response.

Throughout the month, there was continuous supervision and mentoring with time allocated for reflection. Regular feedback sessions focused on providing constructive appraisals and encouraging self-directed learning. Assessment methods emphasized the competencies and included multi-source assessment and structured discussions. The final evaluation was based on the concluding presentation of the team’s achievements to the WHO Representative for Liberia, provided in part by the fellow.

The volatile outbreak situation gave rise to a number of difficulties that challenged the team in adhering to the requirements of the rotation. Long working hours would have been considered a violation of the ACGME duty hours. The outbreak setting constantly challenges one’s skills, both technical and interpersonal. An example is the need to negotiate with local health managers and partners to align everyone’s efforts and work with the inefficiencies inherent in resource-limited settings. However, these seemingly uncomfortable circumstances strengthened the experience in providing a holistic perspective in problem solving.

The team’s work received commendations from both the WHO Country Office, Liberia and local leaderships. Upon return, the experience was shared with audiences including medical students, residents and senior doctors, nurses, and staff of the Singapore Ministry of Health. Stories from the field were widely deemed to add value to the Singaporean preparedness efforts.

The posting fulfilled all criteria previously proposed for international health electives43.The fellow provided meaningful service to the host nation and this was relevant in the trainee’s home setting. The posting helped the trainee in analyzing her career aspirations and becoming a focal point by sharing the experiences with future aspirants. In 2010, the Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training provided advice for institutions and trainees on ethics and best practices54. This elective conformed to the guidelines which are appropriate and intuitive. A structured program was developed and adhered to so that “host and sender as well as other stakeholders derived mutual, equitable benefits”.

There is strong evidence of benefits of global health training across the ACGME core competencies65. Despite the high level of interest from learners, there is no formal registry of residency programs in the US or anywhere to our knowledge that offers formalized global health electives as part of a training curriculum.

Infectious disease is a unique domain in medicine. Its far-reaching scope disregards geographical and socioeconomic divides. In recent decades, public health emergencies have become larger in scale following closer commercial ties and exponential growth in international travel. Infection control and outbreak management at a global level, therefore, should have greater emphasis in infectious disease training. Increased opportunities for hands-on experience is an ideal mechanism. Conventional residency requirements are limited to the theories of infection control and outbreak investigations, and methods of evaluation are generally multiple-choice questions and discussions on hypothetical scenarios. Beyond gaining technical knowledge, participating in a public health outbreak response instills important skills in leadership, including adaptability to complex and evolving situations, working with people of various backgrounds and expectations, communications and dealing with team dynamics.

The benefits of such an initiative go beyond training however. A youthful inexperienced fellow adds diversity to an outbreak response team and with that comes “fresh eyes”, new perspectives and indeed some skills beyond the experienced campaigner. They are well versed with information technology, social networking capacities and other web-based platforms, which may provide practical solutions in communications, data sharing, and maintenance of key indicators especially in resource-poor settings. Trainees may also better connect with ground staff which can be used to the team’s advantage in implementation of policies and soliciting feedback.

In the wake of the response to the Ebola outbreak, the WHO reform agenda includes six key items, one of which is the development of a global health emergency workforce76. Indeed, with this proclaimed proactive, longer term view, it would seem remiss to not engage enthusiastic trainees who are still deciding a career path.

Outbreak response skills in infectious disease physicians are required globally but residency accreditation bodies have yet to recognize their role in facilitating supervised experiential learning. Residency training needs to be more flexible in its scheduling and supervision requirements. Outbreaks are unpredictable in time and location. Residents should be allowed to shuffle their postings to apply for a position in outbreak investigation teams or organizations. Faculty supervisors in this setting can be a short-term appointment with the condition of their adherence to training requirements including appropriate guidance, teaching and evaluation. Not every outbreak is a suitable learning opportunity. A set of criteria, weighing the potential systemic and personal benefits and risks, can be drawn up to evaluate each outbreak for training. This can aid the training accreditation bodies and sponsoring institutions to come to a consensus.

This successful elective posting illustrated how quality training was achieved, even in this most challenging environment. Residency accreditation bodies could adapt to encourage and facilitate such postings which in addition benefits the overall outbreak response and contributes towards building a future global health emergency workforce.

Fig. 1: Meeting residency educational requirements during Ebola outbreak deployment: framework of competency-based goals and objectives and assessment methods. *There was no direct patient contact.

Competing Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Article

The Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an alphavirus that belongs to the Semliki Forest Virus antigenic complex1. Local outbreaks of CHIKV-like disease have been documented since the eighteenth century2 and the virus was discovered in 1952 in Tanzania3 . Over the last 50 years, CHIKV has spread beyond its African heartlands and caused explosive outbreaks comprising millions of cases in Indian Ocean islands and Asia.4The virus is mosquito-borne and transmission is associated with the vector species Aedes albopictus and Ae. aegypti, which are responsible for transmission cycles in urban and peri-urban environments5. Clinical symptoms include polyarthralgia, rash, high fever and severe headaches6 and outbreaks are often characterized by a rapid spread and high morbidity, resulting in losses in productivity7. To date, four distinct CHIKV genotypes have been identified. Two genotypes – the East-Central-South African (ECSA) and the West African genotypes – occupy a basal position in the phylogeny of CHIKV8 and are mostly enzootic in Africa. Of the remaining two genotypes, the Asian genotype is predominant in Southeast Asia, whilst the more recent Indian Ocean lineage spread from the Comoros islands in 2004 and caused a large outbreak in India and Southeast Asia in 2005-2008.

In October 2013, the Asian genotype was first reported in the Americas, in the island of Saint Martin in the Caribbean9. By the end of December 2015, nearly 1 million cases had been notified in the Americas, resulting in 71 deaths, and autochthonous transmission has been reported in more than 50 territories10. In September 2014 the Brazilian Ministry of Health confirmed autochthonous transmission of CHIKV in the Amapá federal state, which borders French Guiana in northern Brazil, and in Feira de Santana (FSA), a well-connected municipality and the second largest city (617,528 inhabitants in 2015, www.ibge.gov.br) of Bahia federal state (BA, northeast of Brazil, where both Aedes vectors circulate11. Genome sequencing revealed that the Asian genotype was circulating in the north of the country. However, 3 genomes sampled from FSA revealed that a distinct lineage, the ECSA genotype, had entered the Americas for the first time12. The ECSA genotype in FSA is closely related to CHIKV strains circulating in Angola. Despite sparse data on CHIKV in Angola, there are recent reports of CHIKV cases exported from Angola to other locations13. Angola is climatically suitable for Aedes spp. mosquitoes11,14 and CHIKV was previously isolated from Aedes aegypti in Luanda15. As a result of the two independent introductions of distinct CHIKV genotypes into Brazil, epidemiological analysis suggests that ~94% of the Brazilian population is at risk of CHIKV infection12. In 2015, the Brazilian Ministry of Health has notified a total of 20,661 CHIKV suspected cases – 7,823 (38%) of these have been confirmed with clinical (35%) and laboratory (3%) confirmation16 across 84 cities in Brazil – of which Feira de Santana has notified by far the greatest number of cases (4,088 only in 2015). It is likely that these numbers represent only a fraction of the individuals infected because CHIKV cases based on clinical diagnosis may be mistaken for dengue virus (DENV) or Zika virus (ZIKV) infection. DENV is hyperendemic in the country, with serotypes 1 to 3 being re-introduced every 7 to 10 years from other South American countries and the Caribbean17,18. Also, autochthonous transmission of ZIKV has recently been reported in several Brazilian federal states16, and although the origins of the virus remain less understood19, recent surveys indicate autochthonous transmission of ZIKV in 19 out of 27 federal states in Brazil.

The Brazilian surveillance health system (Sistema Nacional de Notificação de Agravos, www.saude.gov.br/sinanweb) defines a CHIKV suspected/notified case as an individual presenting with a sudden fever (>38.5 C) and arthralgia or intense acute arthritis that cannot be explained by other conditions, with the patient being either a resident or having visited endemic or epidemic areas two weeks prior to the onset of symptoms. A CHIKV confirmed case involves either epidemiological or laboratory confirmation through IgM serology, virus isolation, RT-PCR, or ELISA. In FSA, following the first RT-PCR and ELISA confirmed CHIKV cases in June 2014, CHIKV incidence was determined by epidemiological criteria on the basis of severe polyarthralgia or on the chronic evolution of symptoms, which enabled the municipal epidemiological surveillance teams to distinguish CHIKV from DENV and ZIKV infection.

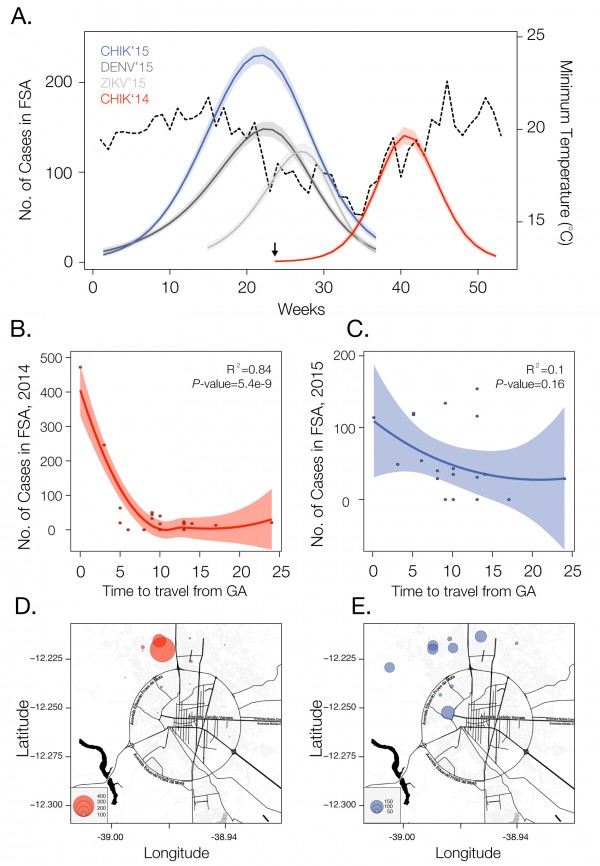

We analysed temporal changes in CHIKV incidence among 21 urban districts of FSA between 1st June 2014 and 1st September 201520. The data show evidence of a shift from a phase of epidemic establishment (June 2014 to December 2014) towards a pattern of transmission behaviour that matches well the annual incidence of DENV (Fig. 1a). Epidemiological surveys indicate that the ECSA index case visited the local polyclinic after arriving in the George Américo (GA) urban district in FSA on the 29th May 2014. The individual presented high fever and polyarthralgia and tested negative for DENV and malaria. Several family members and neighbours of the index case presented CHIKV-like symptoms in June 2014. As expected for a newly-emergent epidemic, we find that travelling time from the inferred epidemic origin (GA) to other locations, measured as the driving time in minutes from GA to the centre of each urban district, is inversely associated with incidence during the earliest stages of the outbreak. Specifically, we find a strong and significant correlation between travelling time and incidence during 2014 (R2=0.84; p-value<0.0001; Fig. 1b). However, during the second epidemic wave in 2015, the relationship between incidence and travelling time to the epidemic origin is considerably weaker and more diffuse (R2=0.1014; p-value=0.16; Fig. 1c). Further, the incidence time series for 2015 has shifted towards the annual pattern typically observed for DENV (Fig. 1a), which is driven primarily by seasonal cycles in vector abundance21. This supports the hypothesis that CHIKV has transitioned from epidemic establishment caused by spatial dissemination from the location into which the virus was introduced to a pattern in which multiple neighbourhoods are now acting as secondary foci of transmission.

Incidence of CHIKV, DENV and ZIKV (number of clinically confirmed cases) in Feira de Santana (FSA) district, Bahia state, Brazil. The red curve shows CHIKV incidence between weeks 13 and 53 in 2014 (an arrow indicates the arrival date of the index case to George Américo, GA, district)). The blue curve shows incidence between weeks 1 and 35 in 2015. For comparison, the numbers of DENV (dark grey) and ZIKV (light grey) cases in 2015 are shown20. Curve fitting to incidence time-series data was performed using Poisson-smoothing in R software22. Panel (b) shows the correlation (R2 and p-value) between the estimated travel time (minutes) from GA to the geographic centre of each other urban district of residence in FSA presenting more than 10 cases in either 2014 or 2015, against the 2015 CHIKV incidence for each district in FSA. Panel (c) shows the equivalent results for 2014. Only urban districts with >10 reported cases in either year were considered. A map of Feira de Santana is shown with the number of cases per district of residence for 2014 (d) and 2015 (e).

Fig. 1: Dynamics of Chikungunya in Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil, in 2014-2015

Current data gives no indication that an endemic cycle will not be repeated in future years, as it is for DENV. Even if after the second cycle of CHIKV in FSA transmission is halted, as in the 2005-2006 outbreak in La Reunion23, it is likely that the virus will continue to spread in geographic areas with immunologically naïve hosts and an abundance of Ae. aegypti and/or Ae. albopictus. Both species are widely present in Brazil11 and are suitable vectors for the ECSA and Asian genotypes24. Future CHIKV transmission cycles are expected to be in phase with dengue and ZIKV seasonal epidemics, peaking when temperature, precipitation and humidity are propitious for Aedes-mediated transmission25. In addition, there is the potential for CHIKV to become endemic in the region, with occasional epidemics in humans. There is some evidence that CHIKV maintains an enzootic cycle in Southeast Asia involving nonhuman primates and forest-dwelling mosquitoes26, similar to the transmission of yellow fever virus in the Amazon and Orinoco river basin 27.

Since the establishment of CHIKV in FSA, the city has been experiencing a near-collapse of the public health system. The number of reported cases has already surpassed 5,363 but the local health care officials suspect that only 20% of cases are being notified. Although no treatment is available, several compounds and vaccines are currently under development28. More generally, the establishment of the ECSA genotype in Brazil is an unprecedented event in the Americas. This lineage is known to have acquired several adaptive mutations to Aedes albopictus. For example, a single amino acid mutation in its glycoprotein E1 (A226V) has been shown to confer 50-100 fold increases in transmissibility in this species29. Continued epidemiological and genetic surveillance and classification of CHIKV genotypes in Brazil and elsewhere in the Americas will be essential to monitor virus diversity, the acquisition of mutations related to viral reproductive success and vector specificity. In addition, along with ongoing DENV transmission, ZIKV is also spreading rapidly throughout northern Brazil19,30, and 1,459 suspected ZIKV cases have been reported until the 23 November 2015 in FSA17. The patterns of ZIKV match relatively well the epidemic cycles of DENV and CHIKV in 2015 and molecular epidemiological analyses are confirm that the CHIKV-ECSA strain has been circulating in Bahia state during 2015 (unpublished findings). Notably, the seasonal 2015 patterns of the arboviruses appear synchronized, especially in terms of their annual demise. These patterns reflect natural temperature cycles (Fig. 1a), which severely affect entomological and viral factors. Particularly, vector capacity is reduced when the temperature drops below 20 degrees Celsius, and transmission is completely disrupted once the temperature reaches 15 degrees Celsius21,25

Other outbreaks of infectious disease have benefited from the use of digital surveillance for enhanced detection and response. Human mobility underlies many phenomena, including the spread of infectious diseases31,32 and high-resolution datasets that represent regional human population density and global mosquito vector densities have recently become available11,33. We have shown here that even the simplest mobility measures may be highly informative of virus spread. Anonymous mobile phone data may also provide a valuable source of information about patterns of human travel and could contribute to better forecasting of disease spread through space and time. Prediction of the dynamics and future disease burden of CHIKV in Brazil would benefit from the inclusion of temperature and precipitation variables that affect vector distributions11,21,25. In addition, high-resolution maps of the Aedes albopictus vector could complement LIRAa (Levantamento Rápido do Indice de Infestação por Aedes aegypti, http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/), which is currently focused on mapping the infestation by Aedes aegypti. Finally, we note that it is exceptional for CHIKV, DENV and ZIKV to be all simultaneously circulating in one single city with < 1 million people. Such a scenario calls for national and international efforts to understand drivers of transmission, curb arbovirus transmission, train public health professionals to provide health care for the infected and effectively control mosquito populations in this municipality and beyond.

Competing Interests

We declare we have no conflict of interests.

Introduction

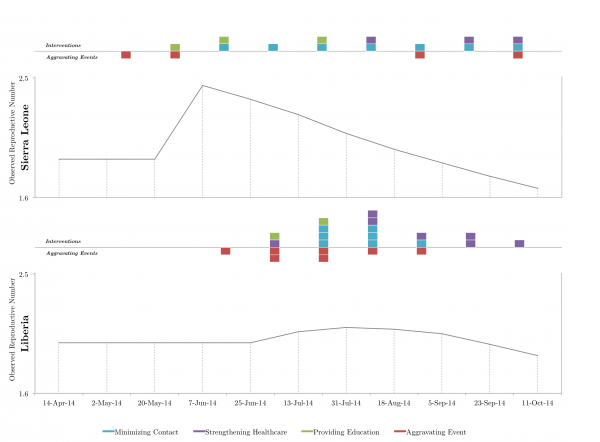

On numerous occasions in the three West African countries most affected by the recent Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak – Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea – violence erupted, ranging from incidents of rocks thrown at Red Cross vehicles to a massacre leaving eight dead at Macenta. Behind the violence lie deeper causes of distrust – failures of communication, lack of engagement with local communities, adverse publicity, and strained relations between local populations, government authorities, and outside agencies. This distrust and violence provoked concealment of cases, unsafe burial practices, refusal to report contacts, and disruption to clinics, burials, and healthcare. In turn, these factors contributed to the startling spread and persistence of EVD.

Violent resistance to the control of EVD was especially marked in Guinea1,2, but episodes flared in Sierra Leone and Liberia. To list a few, first for Guinea: at Macenta on 5 April 2014, urban youth attacked the town’s first EVD clinic constructed a week earlier, and threatened fifty or more of the centre’s personnel. The protesters claimed EVD did not exist or was spread by outsiders2. At Nzérékoré on 29 August, spraying disinfectants through its busy market sparked attacks on the EVD hospital and health workers, leaving twenty-two wounded2. Sometime before 27 July, villagers at Wabengou blockaded roads and attacked officials ‘rushing [against] its cars, banging on the vehicles and brandishing machetes’, according to Doctors Without Borders.3 Then on 16 September, at Womey, West Africa experienced its worst EVD atrocity when eight members of a high-level delegation of doctors, politicians, and journalists were killed and their bodies dumped in a latrine.4 The general level of violence was, however, more pervasive than reported in the international press. In Guinea alone, reported attacks against Red Cross volunteers averaged ten per month in the last six months of 20142.

Although no violence comparable to Womey’s happened in Liberia or Sierra Leone, EVD sparked in these countries open and collective attacks. At Matainkay, east of Freetown, Sierra Leone, on 20 September 2014, villagers assailed health workers while they buried EVD victims, and in December, the Red Cross reported further attacks on their burial teams with damages to their vehicles.5 In Liberia at Westpoint, a poor township in Monrovia, an angry mob overran a health care facility, brought out all patients isolated there and looted the clinic.6

Such reports may give an impression of a violent, irrational people, resisting health care workers and government officials, whose only wish had been to aid an afflicted people. But how do we explain this resistance, and how have West Africans understood their actions? Were such reactions to epidemic disease new, specific to EVD, or to Africa? Are there historical precedents that can aid our understanding of the ways certain epidemic diseases have provoked conflicts and violence during epidemics?

Ebola Virus Disease and Cholera

Suspicions and violence against health workers during epidemics have not been unique to Africa, EVD, or the recent past. Instead, the historical record clearly shows that while some diseases, even with rapid contagion or high levels of mortality, brought societies together as with Yellow Fever in nineteenth-century America7 and the Great Influenza of 1918-19 globally8,9, others have possessed potent social toxins. One to have riddled European history with violence was cholera and not only during its first pan-European tour of the 1830s. In places such as Italy and Russia, this violence continued into the twentieth century and the number of communities that revolted even expanded over time8.

Certain comments and protest slogans, such as ‘Ebola is a lie!’4 and ‘Here, if the people come in [to the hospital], they don’t leave alive’3 recall nineteenth-and-early-twentieth-century cries during cholera riots in Europe. First, even though Ebola is a virus and cholera’s agent, a bacterium, similarities between the two are striking. Their major symptoms include diarrhoea and vomiting, which cause rapid dehydration; both have manifested extraordinary high case fatality rates of 50 per cent and often more (at least in Africa for the former, and before the twentieth century for the latter)8,10; and the socio-psychological reactions of both have led to collective violence as witnessed with EVD in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Levels of violence and destruction with cholera in Europe greatly exceeded those recently seen with EVD in Africa: for the former, crowds numbering as high as 10,000 rioted and could destroy entire cities as at Hughesofka (present-day Donetsk) and as late as 1892 and with those killed by rioters and subsequent state repression numbering in the hundred.11

In the first pan-European cholera wave of the 1830s, riots spread across Eastern and Western Europe from Sicily to Baltic regions, from central Russia to Ireland and across the Atlantic to cities in South and North America. Moreover, no epidemics have provoked such violent antipathy to the medical profession as cholera (the Black Death of 1348 included), with the murder of physicians, surgeons, pharmacists, and nurses and the ritualistic destruction of hospitals and medical equipment8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

Across strikingly different cultures, economies, and regimes, the content and character of cholera conspiracies, mistrust and the targets of rioters’ wrath were uncannily similar. Without any obvious communication among rioters from New York City to villages in Asiatic Russia similar stories of elites in conjunction with medical professionals masterminding culls of the poor with wilful poisoning repeated themselves and triggered hundreds of riots (see references above).

Few have studied the persistence of cholera’s core myths and class hatred. As late as 1911, during Italy’s last major cholera wave, over twenty riots erupted, comprised of impoverished workers, fruit and vegetable cultivators, fishermen, women and children sparking crowds up to three thousand to burn down cholera hospitals, level town halls and other government buildings, and murder doctors, pharmacists, mayors, army generals, and carabinieri. As with recent EVD, the rioters pictured themselves as defending their relatives and neighbours against imagined state-led plots executed by doctors to poison their communities. The riots concentrated in mainland Southern Italy but also occurred in northern towns as at Segni, north of Rome in October, 1911, when 3,000 attacked doctors, cholera hospitals and municipal buildings8,19.

By the late nineteenth century Cholera protest had also evolved in other directions with quarantine regulations provoking demonstrations and violence. For instance, at the seaside town Civitavecchia, north of Rome, a crowd of 1,800 of ‘tourists and visitors of all classes’ rioted in 1884 against these violations to their freedom. They besieged railway stations and took ‘a freight train by storm’.19 More often, similar to ‘the common sense’ reactions in villages and city districts in Guinea in 20142, protests concerning quarantine cut in the opposite direction: populations rioted because the state had refused to erect barriers to protect communities. Vigilantes led brutal attacks against those escaping infected places as at Monreale (near Palermo) in 1887. Armed with rifles, the monrealesi attacked those fleeing cholera-ridden Palermo, forced the evacuees to camp in fields and stabbed a boy, ‘driven by hunger’, to death.20

As with the violence during recent Ebola riots, the reactions and motives of cholera protesters cannot always be described as ‘irrational’. As early as 1867, ‘mobs’ at Naples attacked government offices because of the national government’s incompetence and irresponsibility in improving the city’s sanitary conditions and infrastructure after years of false promises21. Yet alongside new protests, the old ones have persisted8, even during the present seventh cholera wave beginning in the 1960s. In 1992, for instance, the Venezuelan government blamed cholera’s spread on the poor’s dirty, uncivilized habits, especially their diet of crabs, while the poor accused the government and multinationals of poisoning their food (especially their crabs) to kill them off22. In Brazil similar blame from elites completely neglected the socio-economic roots of cholera and led to the resistance of impoverished residents against the government’s preventive measures23.

However, in other countries – the United States, France, and Britain – cholera riots virtually disappeared after 1832. Clearly, these societies were more successful in easing distrust and class tension brought on by the horrors of cholera. With passage of the Anatomy Act in July 1832, for instance, the British state aimed to reduce mounting fears held by the poor that cholera was a state invention to kill them off and to supply cadavers for the new anatomy schools17. With subsequent cholera waves in the British Isles, only a handful of small riots numbering in the teens, and not the thousands appeared. Yet these differences across time and place have yet to be studied8.

One hypothesis explaining the longevity of cholera riots in Eastern Europe points to the state’s continued ruthless intervention and its draconian quarantine regulations24. But, in Spain, Portugal, and Italy from the 1860s to the end of the century, the reason for cholera riots was often the opposite: state reluctance to impose quarantines sparked crowds to revolt.

Understanding resistance in Liberia

In Liberia various forms of community resistance were reported against measures of surveillance, quarantine, isolation, and treatment, such as denying the disease existed, spreading rumours that EVD was transmitted by intentionally poisoning wells or food, that NGOs or the government had spread it to make money, that NGOs used body parts of EVD victims for profit, that whites had introduced EVD to stop the hunting of apes in forests. As a result, on several occasions Liberians refused to obey quarantine regulations, to report or isolate the afflicted, performed secret and unsafe burials, and, as seen above, attacked health care workers and health facilities.

Community resistance to EVD regulations must be analysed in context. Towards the end of 2014, after the epidemic peaked, the government introduced new policies for contact tracing and active case finding. Hundreds were forced to remain quarantined in their homes, often without adequate food and water. Many were forced to violate the quarantine to buy basic provisions in the markets in order to survive.25 Living conditions among those quarantined were often overcrowded, with lack of basic sanitation and no running water. Add to that the constant fear that a beloved one or indeed oneself might be developing symptoms of a disease that only few survived.

Other inconveniences and insensitivity on the part of the government and health agencies made matters worse for afflicted communities. For instance, at the peak of the epidemic, when ambulances picked up those suspected of being infected and carried them to Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs), health authorities rarely informed the families where their relatives had been taken or if they had tested positive. Authorities failed even to inform families if their loved ones had survived or died, causing local populations to believe that patients simply ‘disappear in the ETUs’. As a result, these centres were seen as death camps from which no one returned alive. Rumours spread that the victims had not died of Ebola but had been murdered in the ETUs to harvest their blood and organs. Such tales were similar to those underlying cholera riots, especially in 1832 in the British Isles, when hospitals were seen as abattoirs producing body parts and cadavers for medical instruction. At Monrovia, a large U.S. army ship, anchored in its harbour, was perceived to collect body parts of the Ebola dead to benefit Americans. Stories circulated of patients being neglected in ETUs or starved to death26, and government and health agencies unwittingly spread negative publicity about EVD and its spread, declaring it was a deadly disease without cure. Such messages fanned fear, contributing, no doubt, to the resistance sketched above.

Increasingly, relatives who died at home were not reported to authorities and buried secretly. These burials were often unsafe and a key vector to new infections. Secret burials mounted in number, because of fear of being quarantined or stigmatized. Furthermore, the enforcement of ‘safe burials’ violated communities’ religious beliefs and customs27. By August 2014, fears worsened when the government ordered all corpses cremated: serious resistance now spread to many communities. Police and military forces were deployed along the road leading to the crematory to protect the “Ebola burners”28. However, the government was accused of being inconsistent in how they performed burial practices. Financial ability or social connections would determine who was cremated and who was buried27,29. The order remained in force until January 2015, when finally a burial ground was created near the Capital, Monrovia.

Such occurrences find historical parallels with cholera, when municipalities also prohibited traditional funerals, burials in churchyards, and especially the Irish wake. Enforcement of these regulations (as in West Africa) led to concealing cases and provoked large-scale riots among immigrants in Bristol, London, Liverpool, Glasgow, Edinburgh, New York City, and other towns during the first European cholera wave. Similar measures had similar consequences in Asiatic Russia, Eastern Europe, the Iberian peninsula, and Italy; yet here governments’ insensitivity persisted longer. Space allows only a brief look at an Italian case from its first cholera wave in 1836-7 to its last major one in 1910-11. Throughout, authorities continued to prohibit non-elites (il popolo) from performing their traditional burial rites, visiting afflicted friends and relations, and viewing the cadavers before burial. Such class-based impositions sparked fears that doctors backed by the state had poisoned the cholera afflicted or had buried them alive, while Italian elites continued to bury their love ones stricken by cholera in traditional ecclesiastical grounds. Seeing their relatives unceremoniously ‘thrown into ditches’ of newly-created cholera grounds outside towns and villages, the popolo in Sicily rioted in numerous places in 183730. The same ensued at the Pugliese town of Ostuni in 1837 with its popolo shouting they would not tolerate it.31 But Italian authorities appear not to have learnt the lessons. During Italy’s last major cholera wave in 1910-11, the state continued to impose the same burial restrictions, provoking fears of poisoning and live burials. But now Ostuni’s collective violence exploded beyond its previous experiences. In mid-November 1910, 3,000 (in a town numbering 18,500) wrecked the cholera hospital, ‘liberated the patients’, paraded them home, burnt down the town hall and offices of the health department, took possession of the town square, attacked health workers, stoned carabinieri, and destroyed doctors’ homes32,33.

Back to Liberia: considering certain government measures, the insensitivity in which they were implemented, the lack of support, and comparisons with Europe’s past, it is surprising that more people did not resist openly. Instead, most Liberians cooperated with the response teams. In the beginning of the epidemic with people dying in the streets, not enough space was available in ETUs, and when a 120-bed ETU in Monrovia opened on 21 September 2014 it became full within hours.34 Often transport was unavailable, and patients were forced to wait days for ambulances or were carried to ETUs by taxis, bikes, or in wheelbarrows. ETUs were understaffed, and everywhere essential materials were lacking. Matters began improving only after the epidemic had peaked: international support began to arrive, and several new ETUs were built.

Community engagement

In virtually all former EVD epidemics in East and Central Africa, violence, community resistance or suspicion was reported, and these experiences resembled those in 2014/15.35,36,37 Anthropologists recommended that in future epidemics communities should be encouraged to be more involved in the medical response so that inhabitants would be seen as allies, not as enemies. In the recent epidemic, the same is demanded: public health measures work only when authorities listen to the affected communities and involve them non-paternalistically, allowing confidence in the health system to develop26,38 The WHO Ebola Interim Assessment Panel in its final report from July 2015 expressed its surprise and dismay on the lack of engaging local communities in the response and that ‘culturally sensitive messages and community engagement were not prioritized’.39 While in the WHO’s document ‘Roadmap for Action’40 community engagement is merely an addendum, the 2015 WHO Strategic Response Plan41 stresses community engagement mainstreaming as one important pillar in the Ebola response with clear outputs and key activities. As a matter of fact, WHO was the first organisation to employ anthropologists in Ebola response teams, recognizing that EVD containment should not only be seen bio-medically but also from a socio-cultural perspective. In the retrospective joint report by Harvard University and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Diseases42 the poor understanding of the importance of community engagement is mentioned as a system weakness but this critique did not lead to any recommendations. Violence, serious social disruptions or workforce- and community safety are not explicitly mentioned in any documents, nor is their historical context.

In conclusion the recent adverse reactions to EVD in Western Africa have not been new to history or unique to Africa. Instead, the distrust and violence seen in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone in 2014/15 parallel Europe’s long encounters with cholera from 1830 into the twentieth century. This European past combined with recent events in West Africa can provide lessons for policy makers. First, authorities and health workers must recognize that some diseases have greater potential to spark distrust and violence than others, and the former tend to be ones with high fatality rates, when victims enter health facilities but few return alive. Second, responsible public health experts must negotiate carefully funeral and burial practices central to the ritual life of Africans as they have been for Europeans. Regulating these matters mindful of infection prevention and epidemiological factors alone, without engaging the afflicted communities or their leaders, not only risks triggering resistance, distrust, and violence; it threatens fanning the spread of the epidemic beyond control, increasing misery and the numbers dying.

Competing Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of WHO.

Methods: The authors reviewed the programmatic approaches taken in the eradication strategies for these two diseases and the unique socio-political contexts in which these strategies are couched. The epidemiology of the last 15 years is compared and contrasted. The specific challenges for both programs are outlined and some key elements for success are highlighted.

Discussion: The success of these eradication programs is contingent upon many factors. Nothing is assured, and progress remains fragile and vulnerable to setbacks. Security must be ensured in guinea worm transmission areas in Africa and polio transmission areas in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Technical solutions alone cannot guarantee eradication. National leadership and continued international focus and support are necessary, today more than ever. The legacy of success would be extraordinary. It would reverberate to future generations in the same way that the eradication of smallpox does for this generation.

]]>Introduction

Smallpox is no longer with us. Rinderpest, a measles-like virus of cattle, was formally declared extinct in 2011.1 What other diseases might follow? This paper looks at some clear candidates that were due for eradication this year and explores the chances of success and remaining obstacles for guinea worm and polio. The race is on.

The classic fable of Æsop is known almost universally by both children and adults. Somehow the tale of an overconfident hare losing a race to a much maligned and slower tortoise has entered our consciousness, although the exact moral lesson is ambiguous. Should we accept the conventional wisdom that ‘slow and steady wins the race’ or is the salient lesson one of not taking on a challenge when filled with hubris; or is it a cautionary tale about having callous over-confidence? Whatever the intention in the fable, there is perhaps a message contained therein that is pertinent to another race – the race to disease eradication. Not since the last case of smallpox in the wild was seen in Somalia in 1977 has a human scourge disappeared from the face of the earth.2 Yet now we are perhaps on the edge of seeing the next plague head to extinction. In 2015, polio and guinea worm can rightly be given the monikers of the hare and tortoise. And the race is not over yet.

Guinea worm, or more properly Dracunculus medinensis (‘little dragon from Medina’), is a member of the nematode family that may well be the ‘fiery serpent’ described in the Old Testament. Certainly it inflicts a terrible burning pain to the sufferer as the worm emerges. Remnants have been found in ancient Egyptian mummies.3 The Ebers papyrus, the famous Egyptian medical text, described a method of extraction that is still in use today.4 And the mode of infection reads like a horror story. After drinking water containing the nematode larvae carried within copepods – a small freshwater crustacean – the sufferer will be blissfully unaware as the female worm goes on to mate with a male worm in a body cavity. The male worm then dies and the fertilized female worm migrates into subcutaneous tissues towards the surface and grows up to 120 centimeters long and as thick as spaghetti. After perhaps a year, it then emerges with excruciating pain through a blister, often on lower limbs, but potentially from almost any bodily site, to deposit larvae on contact with water.5 It is this life cycle that was the first scientifically documented proof of a link between a vector and a disease, made by Alexei Pavlovich Fedchenko in 1870.6 Over a century later it was the pioneering work of Dr. Donald R. Hopkins that set guinea worm on the path to eradication. Then in 1988, ex-President Carter joined the commitment to eradicate this disease, prompted by witnessing a fist-sized abscess in the breast of a Ghanaian woman with a worm at its center.7

Polio has been with us for millennia, and is coincidentally also depicted in Egyptian history. Hieroglyphic steles depict a figure with a withered leg, almost certainly representing the classical manifestation of spinal polio, where a limb becomes paralyzed and later deformed. As for guinea worm, the race to eradicate polio began in 1988 under the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, which brought together a partnership between the World Health Organization (WHO), Rotary International, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and UNICEF.8 At the time, the feasibility of polio eradication was seen in the same light as smallpox had been seen. Eradication criteria were similar in that a vaccine was available and effective; the disease only existed in the human host, with no animal reservoir, and symptoms allowed for surveillance and identification of final cases.

Approaches to eradication

Undeniably both of these programs have made remarkable progress since those first commitments to eradication were made (Fig. 1). Both have reduced endemicity to only a few countries and decreased the global burden of disease by over 99%. The approaches to eradication, however, could hardly be more different. Guinea worm is being defeated without a vaccine, without treatment being available, and behavioral change is central to the effort. Guinea worm’s life cycle is interrupted through simple physical barriers and human behaviors play a key role in their maintenance. For polio, vaccination is the alpha and omega of eradication.

Fig. 1: Cases of guinea worm (left Y axis — ) polio (right Y axis —) from 2001 to 2014.

Guinea worm’s eradication program has focused on the provision of clean water; pipe and cloth filters to prevent ingestion of the worm; larviciding potentially infected water sources; and preventing the reintroduction of copepods into drinking water.11 This last action is key. As the guinea worm emerges from the skin and the burning pain becomes intolerable, the sufferer is inclined to soothe the affected limb in water, whereupon the female worm releases its larvae and re-infects resident copepods. The worm emerges incredibly slowly and extraction involves winding it around a stick a few millimeters a day until, some months later, it is removed intact. During this time patients are housed and wounds are dressed until they no longer pose a risk. The motto for years in the Carter Center and CDC’s ‘Guinea Worm Wrap-up’ was: Detect Every Case, Contain Every Worm!12

Like guinea worm, polio is untreatable, debilitating and disabling. A vaccine is, however, available – and essential – to prevent polio. This has been the cornerstone of the eradication effort from its inception. Once vaccination coverage is consistently high enough in areas where transmission is occurring, the virus ceases to circulate, and then – without an alternative host – ceases to exist. This strategy has seen polio disappear from the Americas, Europe, Oceania and the Western Pacific. Type 2 polio virus (WPV2) has already met with extinction. Type 3 (WPV3) has almost certainly followed with the most recent reported onset in a case in November 2012.13 If certified – following three years of surveillance with confirmed absence – that would leave type 1 as the last remaining wild polio type in existence.

So, is this a slow but steady movement towards certain victory? Will these public health investments be repaid a hundred-fold in decades to come? Perhaps, perhaps not. It is testament to the supreme efforts of the dedicated men and women in public health through the 1970s that smallpox eradication became a reality. It may also be a consequence of their success that the ambitious program to eradicate polio was conceived and committed to; a program that has missed deadlines and is as yet not fulfilled.

Progress and challenges in polio eradication

At the beginning of 2002, the battle to eradicate polio looked near to won, at hare-like speed. The total number of cases globally in 2001 was 483 with only eight cases occurring in non-endemic countries. The number of endemic countries had fallen from 20 in 2001 down to 10 the following year. India had the majority of cases at a mere 268. Yet two years later in 2003 the global total had risen to over 1900 cases and India alone had 1600. Nigeria, which had 28 cases in the year 2000 had 1122 cases by 2006. As quickly as one country would stop transmission, another would become newly infected.14

What had gone wrong? This staggered progress illustrated a number of enormous challenges. India’s backward steps related to several technical, social and logistical challenges. Firstly, there was the challenge of delivering polio vaccines to poor, overcrowded regions, especially in the hugely populated northern states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, where even basic sanitation was often absent. These two states combined had over 500,000 births per month; all requiring vaccination before encountering the virus.15 Parts of Bihar spend almost six months submerged by India’s monsoonal rains, isolating literally thousands of villages and hamlets. Secondly, it was discovered that in these crowded and unsanitary conditions, virus transmission was the most highly efficient in the world.16 Finally, these northern states contained a small but significant percentage of families within a Muslim minority, suspicious of state interventions and concerned the polio vaccine was a means of population control.17

Nigeria demonstrated just how critical trust in the vaccine and those delivering it was to a successful eradication program. In late 2003, the northern states of Nigeria stopped polio vaccination altogether for several months, leading to a massive re-emergence of polio cases. Again the mistrust was in part based around a belief that polio vaccination was a state-sponsored mass fertility control measure. Only with the understanding and support of key religious figures in the north did vaccination recommence. Both northern Nigeria and northern India highlighted yet another substantial threat; that of the trans-boundary export of the virus to other countries. Viruses originating from Nigeria eventually spread to over twenty states across Africa and beyond to Yemen and Indonesia.18

These backward steps changed, however, with the development of what some public health officials called a ‘game-changer’. It was a bivalent oral polio vaccine for sub-types 1 and 3, more effective than the old trivalent and no worse than monovalent for inducing immunity to type 1. It has allowed sub-type 3 to be gradually squeezed out whilst making steady progress against type 1. India, with its enormous eradication challenges, defeated the last pocket of wild polio in January 2011. Nigeria, with unprecedented religious support from imams, had reduced its cases in 2014 to six, compared to 53 the previous year. In August 2015, the African continent will have gone one year without a single polio case for the first time in history. Indeed, its last case of polio may already have occurred and the hare’s confidence is perhaps justified.

Notwithstanding the financial burden of the final mile (now close to one billion USD19 per year), two other substantial obstacles remain; one technical and the other very human. The oral polio vaccine (OPV) has been used in the remaining endemic countries even as developed countries continue to use the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which is injected. The primary reason for this is that the oral form can continue to be shed from the gut of vaccine recipients, thereby contributing to ‘herd immunity’ and increasing de facto population immunity. IPV can’t do that. The downside is that OPV can mutate back to a form of the virus that clinically causes polio and then ‘circulate’ just like wild virus, causing polio in any vulnerable child. Cases continue to occur globally. Only when no cases of wild or vaccine-derived polio occur, all remaining OPV-using countries are expected to simultaneously switch to IPV, but the cost and logistics are both daunting.

The other, and potentially more difficult challenge, is ongoing conflict in the tribal areas of Pakistan. In 2010 Pakistan allowed an expanding outbreak of polio, and 2011 continued to see cases.20 The source of many of these is the administrative region of Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) which saw a very active insurgency and extremely limited access to a large population of children. That changed in July 2014 when Pakistan’s army took control of previously inaccessible areas but this also saw a huge movement of people and the export of cases across the country. Progress has faltered. In 2014, the tenth report of the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) on the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was scathing, labeling Pakistan’s polio program a “disaster” and highlighting the inertia in the response and the widespread pessimism regarding future prospects of eradication.21 The IMB’s entreaty for Pakistan to establish an Emergency Operations Center modeled after Nigeria’s highly successful center for polio and later Ebola has only just been heeded. Proof of effectiveness of the new national and provincial centers is eagerly awaited.

Progress and challenges in guinea worm eradication

The tortoise, meanwhile, in the form of guinea worm’s eradication program, continues to plod along with barely a backwards step. In 2003, Uganda reported its last indigenous case, followed soon by Mauritania, Benin, Côte D’Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Togo in 2006. In February 2011, Niger and Nigeria were recognized for going 12 consecutive months without an indigenous case of guinea worm. For Nigeria it was all the more exceptional given that it was reporting 3.5 million cases annually when the eradication program started.

South Sudan remains the last real bastion for Dracunculiasis, with 1698 cases in 2010. Yet even here, reported cases have consistently dropped year by year.22 There were a mere 70 cases in 2014 and no cases for seven consecutive months to June 2015. This is South Sudan’s “peace dividend”, even as that peace is challenged. As development assistance arrives in a newly independent South Sudan, one can only hope that such progress (and assistance) will accelerate, and that a genuine peace will enable this particular dividend to be won.

Will the tortoise inevitably win this race? Or, as in Zeno’s paradox, will the finish line become ever more inaccessible even as it nears? Guinea worm certainly looks to be moving inexorably towards eradication. Yet in 2010, after a decade of no cases, a disturbing report of 10 cases in Chad occurred, following discovery by a WHO monitoring mission in July. More worryingly, the origin of these cases could not be determined. Every year since 2010 Chad has seen further human cases across a wider geographical area, re-initiating its endemic status. Now Dracunculiasis infections in dogs – first noted in 2012 – is presenting an even more worrying hypothesis. The worm specimens from dogs appear to be morphologically and or genetically confirmed as D. medinensis and indistinguishable from human specimens. It seems that human and canine cases are associated with Chad’s intense fishing industry. Human and canine cases appear to occur following consumption of undercooked or raw fish respectively.23 The way forward for prevention of cases and treatment of contaminated water sources is not entirely clear in this case.

Reflections on the finish line

So the hare, in the polio eradication program, is definitely taking periodic naps. Any hubris that might have existed in the past has been surely tempered by the setbacks of recent years, the backwards steps of Pakistan’s program and the emerging complexity of what lies ahead. The hare may be racing in Africa, but he is currently enjoying his repose in Pakistan.