Methods: The cases analyzed in this study were collected at a private Hospital, from April 2016 to May 2016, during the chikungunya outbreak in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. All cases were submitted to the Real Time RT-PCR for CHIKV genome detection and to anti-CHIKV IgM ELISA. Chikungunya infection was laboratorially confirmed by at least one diagnostic method and, randomly selected positive cases (n=10), were partially sequenced (CHIKV E1 gene) and analyzed.

Results: The results showed that all the samples grouped in ECSA genotype branch and the molecular characterization of the fragment did not reveal the A226V mutation in the Rio de Janeiro strains analyzed, but a K211T amino acid substitution was observed for the first time in all samples and a V156A substitution in two of ten samples.

Conclusions: Phylogenetic analysis and molecular characterization reveals the circulation of the ECSA genotype of CHIKV in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and two amino acids substitutions (K211T and V156A) exclusive to the CHIKV strains obtained during the 2016 epidemic, were reported.

]]>Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an arbovirus belonging to the Togaviridae family, Alphavirus genus causing an acute febrile syndrome with severe and debilitating arthralgia 1,2,3,4. The viral particle is approximately 60-70 nm in diameter and composed of an icosahedral capsid surrounded by a lipid envelope. The viral genome consists of a single stranded positive sense RNA of 12kb in length, which encodes four non-structural proteins (NSP1-4) and five structural proteins (C, E3, E2, 6K and E1) 5,6,7.

CHIKV was first described in 1952 on the Makonde Plains, between Tanzania and Mozambique (East Africa), and since its Discovery, the virus has been responsible for important emerging and re-emerging epidemics in several tropical and temperate regions of the world 8. Distinct CHIKV genotypes have been identified – West African, East-Central South African (ECSA) and Asian. Moreover, the Indian Ocean Lineage (IOL) has emerged in Kenya in 2004 as a descendant lineage of ECSA and caused several outbreaks in Indian Ocean Islands, India and Asia from 2005 to 2014 9,10. Although the Aedes (Ae.) aegypti mosquito has been highlighted as the main vector for the urban cycle of CHIKV, Ae. albopictus has also demonstrated a high vectorial competence for the vírus transmission due to an A226V mutation in the E1 gene of ECSA genotype that generated the IOL and which promoted an increased infectivity in the midgut, dissemination to the salivary glands and transmission 9,12,13,14. A large number of imported and autochthonous cases of CHIKV have been reported in American, Europe and Asian countries since 2006 due to viremic travelers arising from Africa, India and Indian Ocean islands 11,13.

In the Americas, the first autochthonous transmission of the Asian genotype was reported during 2013 in the San Martin Island, Caribbean 14,15 and since then, many autochthonous cases have emerged in Caribbean, United States, Mexico and Central America, South America, including Brazil and Andean countries 16. In Brazil, the first autochthonous cases of the Asian and ECSA genotypes were reported in 2014 in the North and Northeast cities of Oiapoque (Amapá State) and Feira de Santana (Bahia State), respectively 10,17. In 2015, 38,332 chikungunya suspected cases distributed in 696 municipalities were reported and, until the 32nd Epidemiological Week of 2016, a total of 216,102 suspected cases distributed in 2,248 municipalities were reported in the country. Despite the highest incidence of chikungunya cases in the Northern region of Brazil , the virus spread to the Southeast region in 2015 and 18,173 cases were reported during 2016, with 13,058 of those restricted to the city of Rio de Janeiro 18.

The exponential growth of chikungunya cases in Rio de Janeiro represents a serious public health problem, especially due to the current co-circulation with dengue and zika. As both Asian and ECSA genotypes were introduced in Brazil in 2014, the viral surveillance is of great importance to access the impact over a population, as the role of distinct genotypes in the disease severity and chronicity are still not well understood. Moreover, the monitoring and characterization of CHIKV genotypes allow the identification of possible mutations such as the E1-A226V, of described epidemiological impact 9,12. Despite the increased incidence of the disease in the past year, the information of CHIKV genotypes circulating in Brazil is still scarce. Here, we aimed to perform the genotype characterization of CHIKV strains detectedduring the ongoing 2016 outbreak in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Material and Methods

Ethical Statement

The samples analyzed in this study were from the an ongoing project for arbovirus research in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil approved by resolution number CSN196/96 from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation Ethical Committee in Research (CEP 111/000), Ministry of Health-Brazil. All participating subjects provided a written consent.

Clinical samples

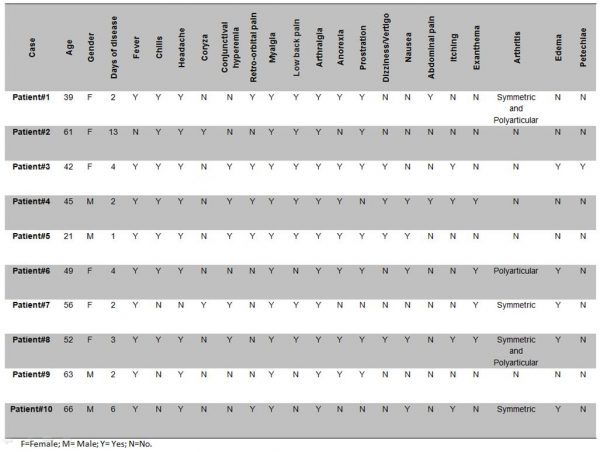

The plasma samples analyzed in this study were collected from April 2016 to May 2016 during the chikungunya outbreak in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Patients were assisted at the Hospital Rio Laranjeiras (HRL) where an infectious disease physician collected data on demographic characteristics, symptoms and physical signs using a structured questionnaire. Chikungunya suspected cases (n=91) were obtained during an active surveillance performed by the Laboratory of Viral Immunology, IOC/FIOCRUZ. All cases were submitted to the Real Time RT-PCR for CHIKV genome detection 19 and to the anti-CHIKV ELISA IgM kit (Euroimmun, Lubeck, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Chikungunya infection was laboratorially confirmed by at least one diagnostic method in 76.97% (70/91) of the cases, 48.57 (34/70) by serology and 84.28 (59/70), by Real Time RT-PCR. Moreover, 35.85% (23/70) of the cases were confirmed by both methods. Chikungunya positive cases (n=10) by Real Time RT-PCR, were randomly selected for partial sequencing (E1 gene) and phylogenetic analysis. The epidemiological data and clinical manifestations from the confirmed cases sequenced in this study are available on Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Epidemiological data and clinical manifestations from the chikungunya confirmed cases (n=10) sequenced in this study.

Chikungunya virus genome amplification, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The fragments generated were purified using PCR Purification Kit or Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Germany) and sequenced in both directions using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction version 3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems®, California, USA). The thermocycling conditions consisted of 40 cycles of denaturation (94°C/10 sec), annealing (50°C/5 sec) and extension (60°C/4 min). Sequencing was performed on an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer, Applied Biosystems®, California, USA 21. The sequences analysis was performed using BioEdit (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.htmL), sequences’ identity was performed using BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and alignments using CLUSTAL OMEGA (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The data set was constructed with sequences previously deposited on GenBank and representative of each genotype and with sequences identified using BLAST. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the MEGA 6 (http://www.megasoftware.net/), by the “Neighbor-Joining” method and Maximum-Likelihood, Kimura-2 parameter model (K2), with a bootstrap of 1,000 replications. Both methods were used as confirmation of the results. The trees was built based on the analysis of the best fit for model, as provided by the software. Partial CHIKV genome sequences were deposited in GenBank and accession number were as follow: KX966400 to KX966409.

Results

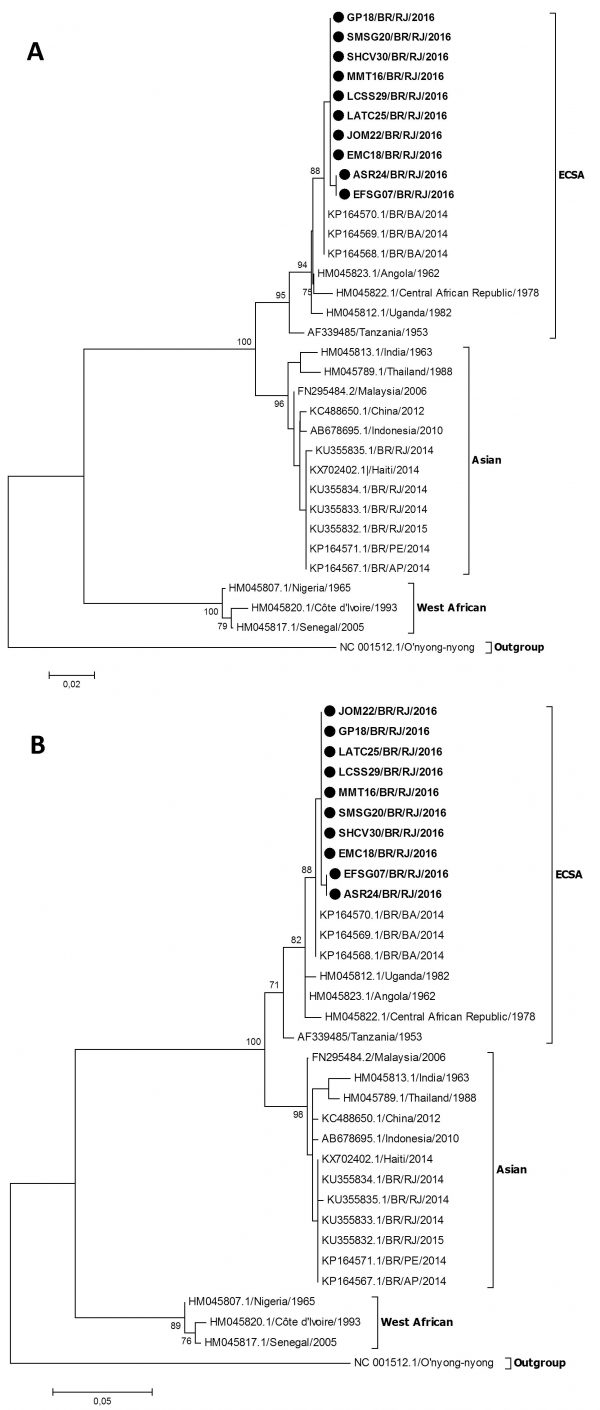

The molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of representative strains (n=10) of CHIKV detected in infected patients during the 2016 outbreak in Rio de Janeiro was performed in comparison to reference sequences available on Genbank and were used to represent the Asian, ECSA and West Africa genotypes. The results, based on a 375-basepair fragment, showed that all the analyzed strains grouped in the ECSA genotype branch, together with a sequence from a sample identified in Bahia in 2014 (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Genotyping of CHIKV strains (n=10) identified in Rio de Janeiro during the outbreak occurred in 2016. Neighbor Joining method (A) and Maximum-Likelihood (B), both K2 parameters model, bootstrap of 1,000 replications. The CHIKV sequences analyzed are represented by black circles. CHIKV strains were named as follows: GenBank accession number (or name strain)/country/year. The O’nyong nyong virus was used as outgroup.

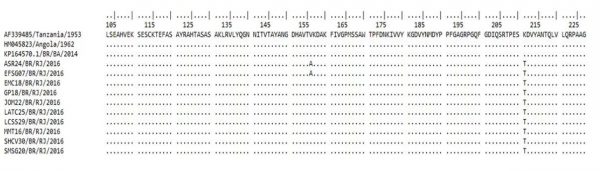

The molecular characterization of the E1 fragment revealed that the alanine amino acid was present at the E226 position, showing no A226V mutation. Interestingly, a K211T amino acid substitution was identified in all analyzed samples and a V156A substitution was identified in two samples of this study (Figure 3). Furthermore, the CHIKV sequences identified in Bahia belonging to the ECSA genotype did not show this substitution at the 211 amino acid and where a lysine (K) is found in the prototype.

Fig. 3: Analysis of the amino acid substitutions (positions 103 to 227) based on partial sequencing of the envelope 1 (E1) gene of the CHIKV ECSA genotype identified during the 2016 outbreak in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. V: Valine; T: Treonine; K: Lisine; A: Alanine.

Discussion and Conclusions

CHIKV has been responsible for important emerging and reemerging epidemics characterized by severe and incapacitating polyarthralgia syndrome 8,22. Due to the intense movement of viremic travelers arising from Africa, India and Indian Ocean islands, many imported cases of the disease were reported on American, European and Asian countries since 2006 11,13.

The high vector density, the presence of susceptible individuals and the intense movement of people has characterized Brazil as a country of major risk for the occurrence of epidemics by arboviruses. After its introduction, CHIKV has caused outbreaks in many regions of Brazil, mainly affecting the Northern region. Despite that, the Southeast Region has played an important role in the disease epidemiology, as imported cases were reported since 2010 and most autochthonous CHIKV cases during 2015 and 2016 18,23.

The exponential growth of CHIKV cases in Rio de Janeiro represents a serious public health problem and the co-circulation of three arboviruses (DENV, CHIKV and ZIKV) results in difficult differential diagnosis 24. Prior to this study, no phylogenetic information was available on the autochthonous CHIKV strains circulating in Rio de Janeiro and, the data available was from the Asian genotype characterized in imported cases analyzed in 2014 and 2015 25.

From our knowledge, this is the first report on the ECSA genotype circulation during the 2016 outbreak in Rio de Janeiro. This genotype was first reported in Feira de Santana, Bahia, Northeast region of Brazil, during 2014 and studies revealed that the strains originated from Angola (West Africa). Moreover, it was the first time that this genotype was reported in Americas. The other CHIKV introduction in Brazil was from the Asian genotype in Oiapoque, Amapá, North Brazil, also during 2014 and, studies revealed that those strains were originated from the Caribbean and South America 10,17,26. Additionally, the molecular characterization the E1 gene fragment analyzed showed that an alanine was present at the E226 position, therefore showing no A226V mutation. Studies performed during the 2005-2006 epidemic occurred in the Reunion Island characterized that this mutation was responsible for generating the IOL, responsible for an increased CHIKV transmission by the vector Ae. albopictus 9,12,13,14. Furthermore, the E1 gene represents a target region for this analysis due to the high antigenic variability, role in the attachment, viral entry into target cells and viral replication during CHIKV infection 7,27. However, this study revealed a K211T amino acid substitution in all samples analyzed and a V156A substitution in two sequences. The former substitution was not identified in the strains from Bahia, which has a Lysine (K) as in the reference strain (Angola/1962). Further studies are needed to clarify the consequences of those mutations, including to the mosquitoes fitness and the human immune system, but other studies suggest that new mutations such as L210Q, I211T and G60D in the E2 region of the IOL also offer advantages for the transmission of CHIKV by Ae. albopictus 18,28,29. The mutations K211E on E1 and V264A on E2 were reported to impact Ae. aegypti ‘s fitness in India during the 2006 to 2010 epidemic 30,31.

This study provides the first genotype surveillance of autochthonous CHIKV cases during the 2016 epidemic in Rio de Janeiro and stress the need for monitoring the spread of the distinct genotypes and the identification of possible mutations that may facilitate the viral transmission by the mosquitoes’ vectors. None of the chikungunya patients were hospitalized or had other complications related to classic rheumatologic chikungunya syndrome. Rio de Janeiro is an important port of entrance and spread of arboviruses, as observed for the distinct DENV serotypes. The recent events occurred in Rio de Janeiro also reinforces the need for viruses’ surveillance and characterization.

Authors’ contributions

FBS and FBN designed the study. TMAS and FBN implemented the sequencing study, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. PCGN, JBC, FPP, LSB and MCC collected and processed the samples. TCC and NRCF analyzed the data. PVD and CS assisted the patients during cases investigation and samples collection. ELA and RMRN provided the laboratory structure and funding for carrying out the experiments. FBS is the guarantor of the paper.

Equal contribution

Flavia Barreto dos Santos and Fernanda de Bruycker-Nogueira contributed equally to the work

Competing interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Data availability statement

Partial CHIKV genome sequences data are available in GenBank with the following accession numbers: KX966400, KX966401, KX966402, KX966403, KX966404, KX966405, KX966406, KX966407, KX966408 and KX966409.

Corresponding authors

Flavia Barreto dos Santos: [email protected] and Fernanda de Bruycker-Nogueira: [email protected].

Methods: An 18-question self-administered survey was mailed to all households in the identified Key West, Florida neighborhood where a GM mosquito trial has been proposed. This survey was fielded between July 20, 2015 and November 1, 2015. The main outcome variable was opposition to the use of GM mosquitoes. Measures included demographic information and opinions on mosquitoes, mosquito control, and vector-borne diseases.

Results: A majority of survey respondents did not support use of GM mosquitoes as a mosquito control method.

Discussion: Reasons for opposition included general fears about possible harmful impacts of this intervention, specific worries about human and animal health impacts from the GM mosquitoes, and environmental concerns about potential negative effects on the ecosystem. Residents were more likely to oppose GM mosquito use if they had a low perception of the potential risks posed by diseases like dengue and chikungunya, if they were female, and if they were less concerned about the need to control mosquitoes in general. These findings suggest a need for new approaches to risk communication, including educational efforts surrounding mosquito control and reciprocal dialogue between residents and public health officials.

]]>Introduction

Mosquito-borne infectious diseases have been a continual threat to human health for millennia and, with the recent emergence of Zika virus, have been recognized more fully as a potential concern in the US. Myriad types of mosquitoes spread many different pathogens. Among these mosquitoes the Aedes genus serves as the vector for several epidemiologically significant infections including dengue fever, chikungunya, Yellow Fever, and Zika virus.1,2

While mosquito-borne illnesses are often associated with tropical and sub-tropical climates, the temperate climate of the North American continent has in the past supported autochthonous transmission of diseases like malaria and yellow fever.3,4 Prior to Yellow Fever elimination efforts, which targeted the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in the 1960’s, nearly erasing that vector from the Americas, vector-borne Yellow Fever outbreaks occurred seasonally as far north as Boston.3 Since the 1980s, vector control efforts have been cut back, or been hampered by a lack of effective pesticides, allowing the Aedes species to return to both North and South America and the Caribbean.5 Revised vector surveillance estimates by the CDC show that Aedes aegypti is present over a wider geographic area in the US than previously thought–as far North as New York and Northern California.6 Recently, the Aedes vectors have sparked US outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya in which local transmission has occurred, and autochthonous transmission of Zika virus is expected to occur in the US in the coming months.7 Such outbreaks have major public health and economic implications that have spurred more aggressive control campaigns in some locations in the Southern US and Hawaii.8

In the future, temperature and weather variations have the potential to further expand mosquito habitat ranges and geographic areas with favorable conditions for transmission of vector-borne diseases.9,10 Importantly, concerns about the potential for outbreaks of of Zika virus in the US have grown in recent months, prompting discussion of more aggressive public health and mosquito control responses in the near future.11

Vector control activities directly aim to reduce target vector species population numbers. Locales utilize a mix of methods tailored to the specific environment and the particular mosquito’s unique breeding and biting behaviors. These activities can include aerial and ground level insecticide spraying, larvicides, and – crucial to Aedes control – elimination of mosquito breeding sites through reduction in standing water.

Effective control of mosquito vectors is difficult to accomplish. Standing water control measures rely on high community compliance to achieve meaningful reductions of breeding sites, which are often located on private property. While this intervention is important for control, it is usually not sufficient. In addition to elimination of standing water, insecticides/larvicides have traditionally been a primary method of mosquito control. However, insecticide use for vector control has, in some cases, sparked concern amongst populations desiring a less “toxic” approach.12 The use of some insecticides, like dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (commonly known as DDT) – which are effective against mosquitoes, but can be toxic to humans and animals in certain contexts – has diminished.13 Additionally, in recent years, Aedes mosquitoes in certain regions have become increasingly resistant to some insecticides, rendering this intervention less effective.14

One novel approach to Aedes control that is increasingly being considered is the release of genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes to diminish populations of wild type Aedes mosquitoes.15,16 This technology relies on gene-edited male mosquitoes that are rendered sterile, a characteristic that prevents effective procreation of mosquitoes by outcompeting wild-type males and thereby diminishing population size. Releases of such mosquitoes have occurred in Panama, Brazil, and elsewhere with promising results.17,18

While technologically feasible and seemingly efficacious, GM mosquitoes have generated controversy (as have other GM products) and varied safety-related concerns among the general public.19 Lack of opposition, and moreover, community member approval is essential to the success of GM mosquito vector control initiatives.20,21

In order to better understand public perceptions, knowledge and attitudes surrounding vector control and GM mosquito use, we surveyed members of one community in Key West, Florida, where a trial of GM mosquitos is under consideration as a targeted intervention to reduce Aedes mosquito populations and protect against vector-borne diseases.22 Findings from this study may help public health practitioners and policymakers communicate more effectively with the public around the issue of GM mosquitoes in the future.

Methods

Study Design

Residents in one community in the Florida Keys, in which GM mosquito release is being considered, were surveyed to assess perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and concerns about the use of GM mosquitoes to control vector-borne disease. An 18-question survey, which was developed based on prior surveys and expert opinion, solicited demographic information and opinions on mosquitoes, mosquito control, and vector-borne diseases (Appendix 1). The self-administered survey was mailed to all (456) households in the identified neighborhood and was fielded between July 20, 2015 and November 1, 2015. Of the distributed surveys, 53 were returned as undeliverable. Of the remaining 403 potential household respondents, 22% (n = 89) participated in this study. One response was excluded since very few questions were answered. A total of 88 responses were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were performed to analyze overall trends in survey responses. The Wilcoxon signed-rank statistical hypothesis test was used to assess whether population mean ranks differed between sub-questions when the survey asked participants to rate different mosquito control methods. Multiple logistic regression was used to model opposition to GM mosquitoes on a number of variables, including demographic information and opinions on mosquitoes, mosquito control, and vector-borne diseases collected for each survey respondent. Simple logistic regression was used to evaluate individual relationships between opposition to GM mosquitoes and collected opinions and demographic information. An expanded set of plausible explanatory variables including all variables that showed significance with simple logistic regression was initially analyzed in a full multiple logistic regression model, but it was determined that a more parsimonious model should be explored due to lack of significance for many variables.

Model selection was done using stepwise selection of variables and analysis of the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) values. The final model included 3 variables. Because of the high number of unique patterns, the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was the primary regression diagnostic used to show good model fit (p=0.6568). Multi-collinearity was checked using the “collin” command in STATA, which displays several measures of collinearity, including variance inflation factor (VIF). All variables showed low VIF values (from 1.12-2.12) with a mean VIF of 1.59. Data was missing in a small number of responses. For variables included in the regression analysis, the maximum number of missing data points was 6 (6.74%).

Outcomes

The main outcome variable was opposition to the use of GM mosquitoes. The survey included the question:

“The Florida Keys Mosquito Control District (FKMCD) is considering using the mosquito control method of introducing male mosquitoes that have been genetically modified (GM) to be sterile in order to reduce the mosquito population in [community]. To what extent do you support of oppose this mosquito control approach in [community]?”

The question included 5 categories of response, including strongly support, support, neutral, oppose, and strongly oppose. These responses were divided into two groups, those who specifically opposed GM mosquitoes (included: oppose and strongly oppose) and those who did not (included all other responses), to create a dichotomous outcome variable. A number of potential independent variables were explored (Appendix 1). After initial data exploration, gender; opinions about mosquito nuisance; worry about mosquito-transmitted diseases; likelihood of contracting those diseases; limitations placed on outdoor activities; and the need to control the mosquito population in the community were used as independent variables in the statistical analysis.

This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB # PRO15060289).

Results

Between July 20, 2015 and November 1, 2015, 89 households in a Key West neighborhood (22%) responded to our survey. One insufficiently complete response was excluded. Demographic characteristic of 88 respondents included in our analysis are reported in Table 1.

Question

Responses

Gender (n=87, 99%)

Male (n=40, 46%); Female (n=47, 54%)

Age (n=88, 100%)

18-33 (n=4, 5%); 34-48 (n=13, 15%); 49-64 (n=38, 43%); 65-79 (n=30, 34%); 80 or older (n=3, 3%)

Education (n=85, 97%)

High school degree or equivalent (n=10, 12%); Some college (n=13, 15%); Associate degree (n=14, 16%); Bachelor degree (n=21, 25%); Graduate degree (n=27, 32%)

Residence status

Year round (n=87, 99%); Seasonal (n=1, 1%)

Ownership status (n=86, 98%)

Own home (n=82, 93%); Rent home (n=4, 5%)

Perceptions about Mosquitoes and Mosquito-borne Diseases

Respondents were asked whether they perceived mosquitoes to be a nuisance where they live. Forty-nine percent (n=41) of 83 respondents strongly disagreed, disagreed, or were neutral, while 51% (n=42) strongly agreed or agreed that mosquitoes are a nuisance where they live. Sixty-nine percent of residents (n=60), reported that they rarely or never limit their time outdoors due to mosquitos while 9% (n=27) responded that they sometimes or often limit their time outdoors because of mosquitoes. This question was followed with a yes/no question about whether there is a need to reduce the mosquito populations in their community. Most residents who responded answered “yes” (n=67, 79%)

Participants were also asked about their level of worry about mosquito-spread diseases like dengue fever or chikungunya. Of the 87 respondents to this question, 32 (37%) reported that they “haven’t thought about it” or were “not worried at all,” while a majority (n=55, 63%) were either “a little worried” or “very worried.” This question was followed by a question asking whether residents had known anyone who had been sick with dengue fever or chikungunya. Of the 87 responses to this question, 65 (75%) answered “no” they hadn’t known anyone with these diseases, and 22 (25%) answered “yes.” Residents were then questioned about perceived likelihood that they or someone they know would contract dengue fever or chikungunya while living in their community. A large majority (n=75, 85%) of the 88 total respondents to this question thought that it was “very unlikely,” “unlikely,” or “uncertain” that anyone they knew would contract these diseases. Only 13 (15%) respondents answered that it was “likely” or “very likely” to happen.

Perceptions about Mosquito Control Methods

The survey next asked a succession of questions about mosquito control methods. First, residents were asked to rate a series of mosquito control methods that might be applicable to their community. Respondents were asked to rate each question from 1-5 (1 being the method they supported the most, and 5 being the method supported the least). Based on the mean score of each control method, residents were most supportive of the method of “draining standing water on private property to reduce mosquito breeding” (mean=1.98), followed by treating standing water with larvicides (mean=2.49), spraying pesticides at ground level (mean=3.01), spraying insecticides in the air (mean=3.14), and residents were least supportive of using “GM sterile male mosquitoes to reduce the mosquito population (mean=4.14). The difference in distributions of opinions regarding eliminating standing water from private property and the use of GM mosquitoes to control the mosquito population was found to be statistically significant using the Wilcoxon signed rank test (z=-5.57, p=<0.0001).

Perceptions about GM Mosquitoes

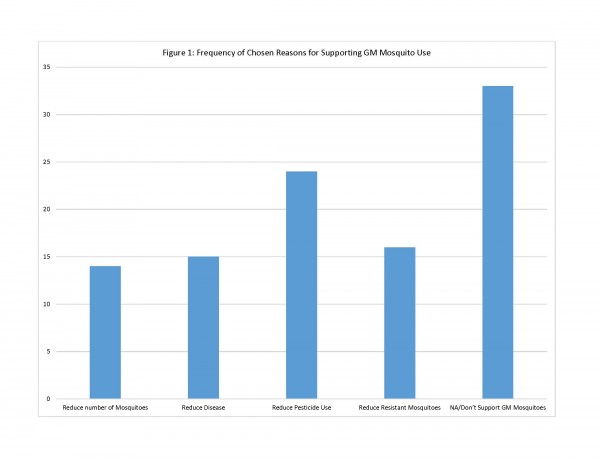

Residents were then asked directly to what extent they support using GM mosquitoes for control in their community. Of the 86 who responded, 50 (58%) said they either “oppose” or “strongly oppose” GM mosquito use, while 36 (42%) were either neutral or “support” or “strongly support” GM mosquito use for vector control in their community. The question about GM mosquito use was followed up with two questions aimed at understanding the reasons behind why they either supported or did not support this control option. Residents were asked to check all reasons that applied. For those who supported or were neutral on GM mosquito use, the survey provided 4 possible reasons for support of this method. Of these reasons for supporting GM mosquito use, respondents chose one reason most often: “GM mosquitoes could reduce the need to use pesticides/larvicides in [community] for mosquito control” (n=24). Other reasons, including reduction in pesticide-resistant mosquitoes (n=16) concern about mosquito-transmitted disease (n=15) and reduction of mosquito nuisance (n=14), were chosen less often (See Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Frequency of Chosen Reasons for Supporting GM Mosquito Use

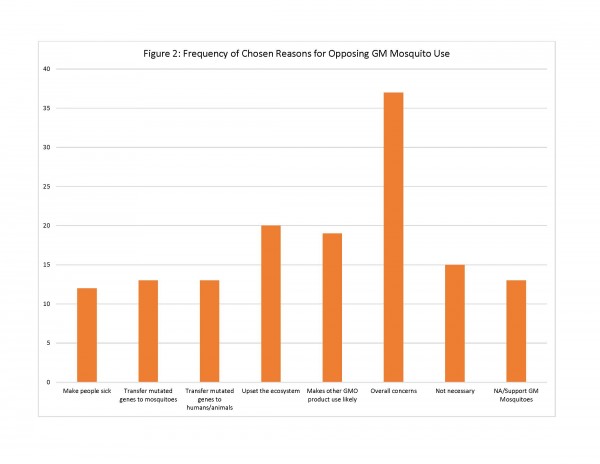

For those residents who did not support GM mosquito use, the survey provided 7 possible reasons for opposition of this method. Of these reasons, respondents chose the following reasons most often: “I am concerned about the overall safety of GM mosquitoes” (n=37); “Introduction of GM mosquitoes could upset the local ecosystem by eliminating mosquitoes from the food chain” (n=20); and “The use of GM mosquitoes could lead to the use of other GMO products in [community]” (n=19). Other reasons included concerns that the mosquito could make people sick and/or pass on modified genes to people and animals, but were chosen less and thus were less important to the respondents (See Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Frequency of Chosen Reasons for Opposing GM Mosquito Use

Residents were asked to characterize how much they had read, heard or seen about the use of GM mosquitoes as a method of mosquito control prior to receiving this survey. A large majority (n=60, 83%) had been exposed to this information “some” or “a lot,” while only 12 (17%) of the residents who responded had read, heard, or seen “not much” or “nothing” on this topic. Finally, the survey asked residents about their opinion of the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District (FKMCD), which is responsible for mosquito control in the community of interest. Overall, most (n=74, 87%) respondents’ had either “very favorable,” “favorable” or “neutral” opinions toward the District, while a minority (n=11, 13%) had “unfavorable” or “very unfavorable” opinions of FKMCD.

Characteristics associated with opposition to GM mosquitoes

Beyond summary statistics, we sought to assess relationships between opposition of GM mosquito use in vector control (dependent variable) and other demographic factors and opinions. First, simple regression was used to evaluate individual relationships between opposition to GM mosquito use and demographic variables. In this analysis only gender was found to be significantly associated with GM mosquito opposition at the p<0.05 level (OR=5.0, p=0.001), with females more likely to oppose use than males.

We then sought to evaluate the relationship between GM opposition and other questions about mosquito control and risk perception. Using simple logistic regression, we found significant associations between GM mosquito opposition and opinions about mosquito nuisance, worry about mosquito-transmitted diseases, likelihood of contracting those diseases, limitations placed on outdoor activities, and the need to control the mosquito population in the community (Table 2). Each of these variables were negatively associated with GM mosquito opposition. If residents considered mosquitoes to be a nuisance, if they worried about dengue and Chikungunya or thought that contracting those diseases was likely, limited outdoor time because of mosquitoes or thought that mosquito control was very important, they were less likely to be opposed to GM mosquitoes. When multiple logistic regression was applied to the same set of variables, only gender (OR=7.47, p=0.002) and Disease likelihood (OR=7.47, p=0.01) had significant associations with GM mosquito opposition at the p<0.05 level (Table 2).

Crude

Adjusted*

Variable

OR

95% CI

P value

OR

95% CI

P value

Gender (female)

5.00

(1.97-12.67)

0.001

7.47

(2.14-26.16)

0.002

Perception of mosquitoes as a nuisance

0.47

(0.29-0.75)

0.002

0.81

(0.42-1.56)

0.520

Worry about mosquito-transmitted diseases

0.37

(0.19-0.74)

0.004

0.82

(0.31-2.18)

0.697

Perception of likelihood of acquiring disease

0.38

(0.22-0.65)

<0.001

0.38

(0.18-0.80)

0.010

Limit outdoor time because of mosquitoes

0.59

(0.36-0.96)

0.033

0.90

(0.43-1.90)

0.780

Need for mosquito control

0.19

(0.05-0.73)

0.016

0.38

(0.07-1.96)

0.249

Because of the lack of significance for many of the variables in the initial adjusted model, a subsequent model was developed. The final model included 3 variables: opinion about the likelihood of contracting a mosquito–transmitted disease, gender, and opinion about the need to control the mosquito population in the community. In this final model, opinion about likelihood of contracting a mosquito–transmitted diseases (OR=0.31, p=0.001) and gender (OR=6.93, p=0.001) were both significantly associated with opposition to GM mosquitoes , with those who considered the likelihood of acquiring a mosquito-borne disease to be low and females being more likely to oppose GM mosquitoes. Opinion about the need to control the mosquito population in the community as a variable was found to be borderline significantly associated with GM mosquito opposition (OR=0.23, p=0.055), with those who supported a greater need to control the mosquito population more likely to support GM mosquitoes (Table 3).

Crude

Adjusted Final*

Variable

OR

95% CI

P value

OR

95% CI

P value

Gender (female)

5.00

(1.97-12.67)

0.001

6.93

(2.13-22.58)

0.001

Perception of likelihood of acquiring disease

0.38

(0.22-0.65)

<0.001

0.31

(0.16-0.60)

0.001

Need for mosquito control

0.19

(0.05-0.73)

0.016

0.23

(0.05-1.03)

0.055

Discussion

Our work represents a baseline evaluation of the level of support or opposition to GM mosquitoes in an area in which their use is being contemplated because of recent experience with both dengue and chikungunya autochthonous transmission. Importantly, this evaluation took place during a time period before Zika virus became a concern and provides foundational information to judge potential changes in attitudes over time and with the introduction of new concerns about mosquito borne diseases. Not surprisingly, the general cultural animus against most things labeled as “genetically modified” extends to genetically modified mosquitoes. However, the nuances of that opposition merit further study and incorporation into public outreach, discussion, dialogue and education efforts surrounding this issue.

Of interest is the marked gender-split with females more likely to be opposed to the use of GM mosquitoes than males. One hypothesis is that this stance reflects broader concerns about genetically modified products that have been shown to be heightened among women, and potential concerns about possible effects on children and future generations.23,24,25,26,27 However, we did not query subjects about the presence of children in their household. A similar gender-skew has been found in studies of vaccine acceptance, with females being less accepting than males.28

The finding that a person’s estimation of the likelihood of contracting dengue or chikungunya strongly influences their acceptance or rejection of GM mosquitoes as a control option is also of particular interest. This finding has strong face-validity in that risk perception strongly influences the countermeasures people will support in a variety of situations.29 Most of our respondents thought it unlikely that they or someone they know would contract one of the listed illnesses, and only a minority of respondents believed local disease transmission to be risk. This finding is puzzling because dengue and chikungunya cases have occurred in Key West in recent years. Local outbreaks have been covered extensively by the local media and the local community was blanketed with information aimed at community engagement, as our group noted in a prior study.8 It is unclear whether the knowledge of the prior outbreaks was extinguished in the minds of many respondents or whether risk perception has just waned since these cases occurred.

An important extension of this work would be evaluate the impact of the 2015-2016 Zika virus outbreak in the Western Hemisphere on awareness, risk perception, and attitudes. Zika is a virus also transmitted by Aedes type mosquitoes. The Zika virus outbreak, occurring in a post-West African Ebola context, has received a very high level of media attention. In Florida, the Governor recently declared public health emergencies in 4 counties due to Zika concerns, despite there being no evidence of autochthonous transmission in the state to date.30 In contrast, no emergency declarations occurred in 2009, or in subsequent years, when there has been autochthonous transmission of dengue in several Florida counties,31 or in 2014, when the first locally acquired chikungunya case was identified in Florida.32 Zika virus, with its association with adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes, may change the risk perception of those that live in Aedes-laden regions. Adverse pregnancy outcomes might also be a factor in shifting females’ perceptions as they recalibrate risks of Aedes-associated infections with new information about Zika and its potential threats to children. In a recent nationwide survey by Purdue University, 78% of participants supported the use of GM mosquitoes to fight Zika virus.33 While the Purdue study surveyed a much wider population, it may provide an indication of potential changes in public support for GM mosquito use that may emerge as communities face the threat of Zika virus transmission in their neighborhoods. In contrast however, a different nation-wide survey published in February by the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center found that 35% of respondents believed that GM mosquitoes cause the spread of Zika,34 a belief which may reduce local support for GM mosquitoes.

Limitations

The primary limitations of this study are a potential for self-selection bias and non-response bias in the group of respondents. It may be that individuals who were in greater opposition to or more in support of GM mosquito use were more likely to respond to this survey. Thus the survey may not be representative of the beliefs and attitudes of the community at large. This potential limitation may make this study more representative of those residents with strong positive or negative feelings about GM mosquito use. While this is a limitation, the survey still provides insight into how and why motivated and vocal members of this Florida community might support or oppose these vector control options, and can be useful to inform future public health approaches to gathering support for GM mosquitoes or other alternative methods of mosquito control.

Conclusion

We present the first community-based survey of resident attitudes towards GMO mosquitoes in a region of a U.S. state in which Aedes-associated infectious disease risks are extant. Gender and individual risk-perception were found to be highly predictive of support or opposition to GM mosquito use. These findings may help public health practitioners and policymakers to improve communication and dialogue with the public around potential use of GM mosquitoes in the future, which may be increasingly important as new mosquito-borne threats such as Zika emerge.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Data Availability Statement

A link to the survey data can be found here: http://www.upmchealthsecurity.org/our-work/pubs_archive/pubs-pdfs/2016/GM Mosquito Data.pdf

Appendix: Key Haven Mosquito Control Opinion Survey

1) Your Participant ID is: ___________

2) What is your Gender (choose 1 of the following choices)?

• Male

• Female

• Other

3) Do you live in Key Haven permanently, seasonally, or are you just visiting (choose 1)?

• Year round permanent resident (this is my primary residence year round)

• Seasonal resident (I live here less than year round or this is not my primary residence)

• Visitor (I don’t live here, I’m just visiting)

4) If you live in Key Haven year round or seasonally, do you own or rent the property in which you reside on Key Haven (choose 1)?

• I own a home in Key Haven

• Renter

• Other (Please specify)

5) What is your age (choose 1)?

• Less than 18 Years Old

• 18-33 Years Old

• 34-48 Years Old

• 49-64 Years Old

• 65-79 Years Old

• 80 Years Old or Older

6) What is the highest level of school you have completed or the highest degree you have received (choose 1)?

• Less than high school degree

• High school degree or equivalent (e.g., GED)

• Some college but no degree

• Associate degree

• Bachelor degree

• Graduate degree

7) To what extent do you agree with the statement: “Mosquitoes are a nuisance where I live” (choose 1)

• Strongly agree

• Agree

• Neutral

• Disagree

• Strongly disagree

8) How worried are you about dengue fever, chikungunya, and other mosquito-spread diseases (choose 1)?

• Very worried

• A little worried

• Not worried at all

• Haven’t thought about it

9) Do you know anyone who has gotten sick with dengue fever or chikungunya (choose 1)?

• Yes

• No

10) How likely do you think it is that you or someone you know will get dengue fever or chikungunya while you live in Key Haven (choose 1)?

• Very likely

• Somewhat likely

• Uncertain

• Unlikely

• Very unlikely

11) How often do you limit your time outdoors because of mosquitoes (choose 1)?

• Often

• Sometimes

• Rarely

• Never

12) Do you think there is a need to control or reduce mosquito populations in Key Haven (choose 1)?

• Yes

• No

13) If you think mosquito control is needed, rank the mosquito control methods you would support in Key Haven from 1-5 (1 being the method you would support the most, 5 being the method you would support the least).

• Spraying pesticides from the air to kill adult mosquitoes

• Spraying pesticides at ground level to kill adult mosquitoes

• Introducing genetically modified (GM) sterile male mosquitoes to reduce the mosquito population

• Draining standing water on private property to reduce mosquito breeding

• Treating standing water with larvicides to kill young mosquitoes

14) What is your opinion of the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District (FKMCD)?

• Very Favorable

• Favorable

• Neutral

• Unfavorable

• Very Unfavorable

15) The Florida Keys Mosquito Control District (FKMCD) is considering using the mosquito control method of introducing male mosquitoes that have been genetically modified (GM) to be sterile in order to reduce the mosquito population in Key Haven. To what extent do you support or oppose this mosquito control approach in Key Haven?

• Strongly support

• Support

• Neutral

• Oppose

• Strongly oppose

16) If you support or do not oppose the use of genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes in Key Haven, please select the reason(s) for your support from the list below (check all that apply).

• GM mosquitoes could reduce the number of mosquitoes and thus reduce the nuisance of mosquitoes in Key Haven

• GM mosquitoes could reduce the chance that I or someone I know or love will get a mosquito-transmitted disease like dengue fever or chikungunya

• GM mosquitoes could reduce the need to use pesticides/larvicides in Key Haven for mosquito control

• GM mosquitoes could reduce the emergence of pesticide-resistant mosquitoes

• Not applicable, I do NOT support the use of GM mosquitoes

17) If you oppose or do not support the use of genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes in Key Haven, please select the reason(s) for your opposition from the list below (check all that apply).

• GM mosquitoes could bite me or someone I know or love and cause them to become sick

• GM mosquitoes might pass on modified genes to the wild mosquito population

• GM mosquitoes might pass on modified genes to people or animals

• Introduction of GM mosquitoes could upset the local ecosystem by eliminating mosquitoes from the food chain

• The use of GM mosquitoes could lead to the use of other GMO products in Key Haven

• I am concerned about overall safety of GM mosquitoes

• Use of GM mosquitoes is unnecessary because dengue and chikungunya are not serious threats in Key Haven

• Not applicable, I support the use of GM mosquitoes

18) Before today, how much had you read, heard, or seen about the use of genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes as a method of mosquito control?

• A lot

• Some

• Not Much

• Nothing

Article

The Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an alphavirus that belongs to the Semliki Forest Virus antigenic complex1. Local outbreaks of CHIKV-like disease have been documented since the eighteenth century2 and the virus was discovered in 1952 in Tanzania3 . Over the last 50 years, CHIKV has spread beyond its African heartlands and caused explosive outbreaks comprising millions of cases in Indian Ocean islands and Asia.4The virus is mosquito-borne and transmission is associated with the vector species Aedes albopictus and Ae. aegypti, which are responsible for transmission cycles in urban and peri-urban environments5. Clinical symptoms include polyarthralgia, rash, high fever and severe headaches6 and outbreaks are often characterized by a rapid spread and high morbidity, resulting in losses in productivity7. To date, four distinct CHIKV genotypes have been identified. Two genotypes – the East-Central-South African (ECSA) and the West African genotypes – occupy a basal position in the phylogeny of CHIKV8 and are mostly enzootic in Africa. Of the remaining two genotypes, the Asian genotype is predominant in Southeast Asia, whilst the more recent Indian Ocean lineage spread from the Comoros islands in 2004 and caused a large outbreak in India and Southeast Asia in 2005-2008.

In October 2013, the Asian genotype was first reported in the Americas, in the island of Saint Martin in the Caribbean9. By the end of December 2015, nearly 1 million cases had been notified in the Americas, resulting in 71 deaths, and autochthonous transmission has been reported in more than 50 territories10. In September 2014 the Brazilian Ministry of Health confirmed autochthonous transmission of CHIKV in the Amapá federal state, which borders French Guiana in northern Brazil, and in Feira de Santana (FSA), a well-connected municipality and the second largest city (617,528 inhabitants in 2015, www.ibge.gov.br) of Bahia federal state (BA, northeast of Brazil, where both Aedes vectors circulate11. Genome sequencing revealed that the Asian genotype was circulating in the north of the country. However, 3 genomes sampled from FSA revealed that a distinct lineage, the ECSA genotype, had entered the Americas for the first time12. The ECSA genotype in FSA is closely related to CHIKV strains circulating in Angola. Despite sparse data on CHIKV in Angola, there are recent reports of CHIKV cases exported from Angola to other locations13. Angola is climatically suitable for Aedes spp. mosquitoes11,14 and CHIKV was previously isolated from Aedes aegypti in Luanda15. As a result of the two independent introductions of distinct CHIKV genotypes into Brazil, epidemiological analysis suggests that ~94% of the Brazilian population is at risk of CHIKV infection12. In 2015, the Brazilian Ministry of Health has notified a total of 20,661 CHIKV suspected cases – 7,823 (38%) of these have been confirmed with clinical (35%) and laboratory (3%) confirmation16 across 84 cities in Brazil – of which Feira de Santana has notified by far the greatest number of cases (4,088 only in 2015). It is likely that these numbers represent only a fraction of the individuals infected because CHIKV cases based on clinical diagnosis may be mistaken for dengue virus (DENV) or Zika virus (ZIKV) infection. DENV is hyperendemic in the country, with serotypes 1 to 3 being re-introduced every 7 to 10 years from other South American countries and the Caribbean17,18. Also, autochthonous transmission of ZIKV has recently been reported in several Brazilian federal states16, and although the origins of the virus remain less understood19, recent surveys indicate autochthonous transmission of ZIKV in 19 out of 27 federal states in Brazil.

The Brazilian surveillance health system (Sistema Nacional de Notificação de Agravos, www.saude.gov.br/sinanweb) defines a CHIKV suspected/notified case as an individual presenting with a sudden fever (>38.5 C) and arthralgia or intense acute arthritis that cannot be explained by other conditions, with the patient being either a resident or having visited endemic or epidemic areas two weeks prior to the onset of symptoms. A CHIKV confirmed case involves either epidemiological or laboratory confirmation through IgM serology, virus isolation, RT-PCR, or ELISA. In FSA, following the first RT-PCR and ELISA confirmed CHIKV cases in June 2014, CHIKV incidence was determined by epidemiological criteria on the basis of severe polyarthralgia or on the chronic evolution of symptoms, which enabled the municipal epidemiological surveillance teams to distinguish CHIKV from DENV and ZIKV infection.

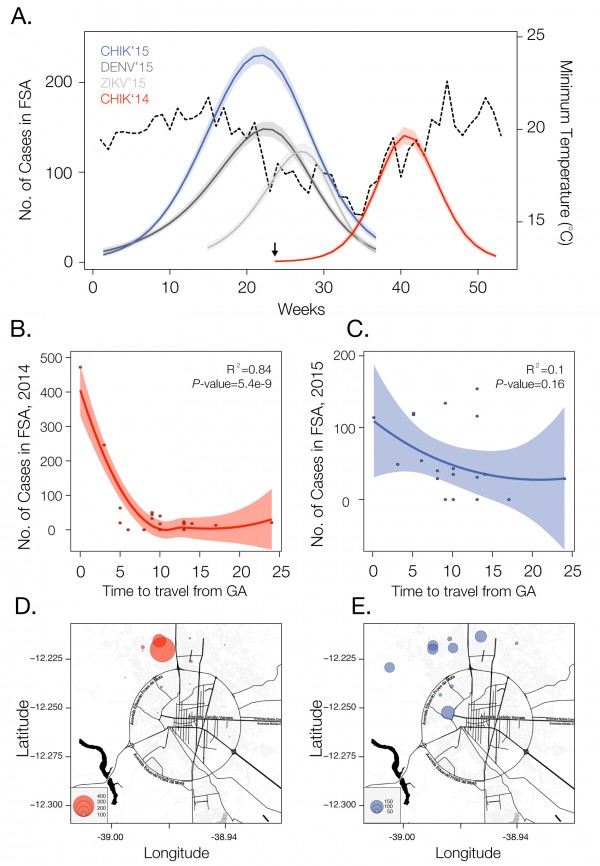

We analysed temporal changes in CHIKV incidence among 21 urban districts of FSA between 1st June 2014 and 1st September 201520. The data show evidence of a shift from a phase of epidemic establishment (June 2014 to December 2014) towards a pattern of transmission behaviour that matches well the annual incidence of DENV (Fig. 1a). Epidemiological surveys indicate that the ECSA index case visited the local polyclinic after arriving in the George Américo (GA) urban district in FSA on the 29th May 2014. The individual presented high fever and polyarthralgia and tested negative for DENV and malaria. Several family members and neighbours of the index case presented CHIKV-like symptoms in June 2014. As expected for a newly-emergent epidemic, we find that travelling time from the inferred epidemic origin (GA) to other locations, measured as the driving time in minutes from GA to the centre of each urban district, is inversely associated with incidence during the earliest stages of the outbreak. Specifically, we find a strong and significant correlation between travelling time and incidence during 2014 (R2=0.84; p-value<0.0001; Fig. 1b). However, during the second epidemic wave in 2015, the relationship between incidence and travelling time to the epidemic origin is considerably weaker and more diffuse (R2=0.1014; p-value=0.16; Fig. 1c). Further, the incidence time series for 2015 has shifted towards the annual pattern typically observed for DENV (Fig. 1a), which is driven primarily by seasonal cycles in vector abundance21. This supports the hypothesis that CHIKV has transitioned from epidemic establishment caused by spatial dissemination from the location into which the virus was introduced to a pattern in which multiple neighbourhoods are now acting as secondary foci of transmission.

Incidence of CHIKV, DENV and ZIKV (number of clinically confirmed cases) in Feira de Santana (FSA) district, Bahia state, Brazil. The red curve shows CHIKV incidence between weeks 13 and 53 in 2014 (an arrow indicates the arrival date of the index case to George Américo, GA, district)). The blue curve shows incidence between weeks 1 and 35 in 2015. For comparison, the numbers of DENV (dark grey) and ZIKV (light grey) cases in 2015 are shown20. Curve fitting to incidence time-series data was performed using Poisson-smoothing in R software22. Panel (b) shows the correlation (R2 and p-value) between the estimated travel time (minutes) from GA to the geographic centre of each other urban district of residence in FSA presenting more than 10 cases in either 2014 or 2015, against the 2015 CHIKV incidence for each district in FSA. Panel (c) shows the equivalent results for 2014. Only urban districts with >10 reported cases in either year were considered. A map of Feira de Santana is shown with the number of cases per district of residence for 2014 (d) and 2015 (e).

Fig. 1: Dynamics of Chikungunya in Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil, in 2014-2015

Current data gives no indication that an endemic cycle will not be repeated in future years, as it is for DENV. Even if after the second cycle of CHIKV in FSA transmission is halted, as in the 2005-2006 outbreak in La Reunion23, it is likely that the virus will continue to spread in geographic areas with immunologically naïve hosts and an abundance of Ae. aegypti and/or Ae. albopictus. Both species are widely present in Brazil11 and are suitable vectors for the ECSA and Asian genotypes24. Future CHIKV transmission cycles are expected to be in phase with dengue and ZIKV seasonal epidemics, peaking when temperature, precipitation and humidity are propitious for Aedes-mediated transmission25. In addition, there is the potential for CHIKV to become endemic in the region, with occasional epidemics in humans. There is some evidence that CHIKV maintains an enzootic cycle in Southeast Asia involving nonhuman primates and forest-dwelling mosquitoes26, similar to the transmission of yellow fever virus in the Amazon and Orinoco river basin 27.

Since the establishment of CHIKV in FSA, the city has been experiencing a near-collapse of the public health system. The number of reported cases has already surpassed 5,363 but the local health care officials suspect that only 20% of cases are being notified. Although no treatment is available, several compounds and vaccines are currently under development28. More generally, the establishment of the ECSA genotype in Brazil is an unprecedented event in the Americas. This lineage is known to have acquired several adaptive mutations to Aedes albopictus. For example, a single amino acid mutation in its glycoprotein E1 (A226V) has been shown to confer 50-100 fold increases in transmissibility in this species29. Continued epidemiological and genetic surveillance and classification of CHIKV genotypes in Brazil and elsewhere in the Americas will be essential to monitor virus diversity, the acquisition of mutations related to viral reproductive success and vector specificity. In addition, along with ongoing DENV transmission, ZIKV is also spreading rapidly throughout northern Brazil19,30, and 1,459 suspected ZIKV cases have been reported until the 23 November 2015 in FSA17. The patterns of ZIKV match relatively well the epidemic cycles of DENV and CHIKV in 2015 and molecular epidemiological analyses are confirm that the CHIKV-ECSA strain has been circulating in Bahia state during 2015 (unpublished findings). Notably, the seasonal 2015 patterns of the arboviruses appear synchronized, especially in terms of their annual demise. These patterns reflect natural temperature cycles (Fig. 1a), which severely affect entomological and viral factors. Particularly, vector capacity is reduced when the temperature drops below 20 degrees Celsius, and transmission is completely disrupted once the temperature reaches 15 degrees Celsius21,25

Other outbreaks of infectious disease have benefited from the use of digital surveillance for enhanced detection and response. Human mobility underlies many phenomena, including the spread of infectious diseases31,32 and high-resolution datasets that represent regional human population density and global mosquito vector densities have recently become available11,33. We have shown here that even the simplest mobility measures may be highly informative of virus spread. Anonymous mobile phone data may also provide a valuable source of information about patterns of human travel and could contribute to better forecasting of disease spread through space and time. Prediction of the dynamics and future disease burden of CHIKV in Brazil would benefit from the inclusion of temperature and precipitation variables that affect vector distributions11,21,25. In addition, high-resolution maps of the Aedes albopictus vector could complement LIRAa (Levantamento Rápido do Indice de Infestação por Aedes aegypti, http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/), which is currently focused on mapping the infestation by Aedes aegypti. Finally, we note that it is exceptional for CHIKV, DENV and ZIKV to be all simultaneously circulating in one single city with < 1 million people. Such a scenario calls for national and international efforts to understand drivers of transmission, curb arbovirus transmission, train public health professionals to provide health care for the infected and effectively control mosquito populations in this municipality and beyond.

Competing Interests

We declare we have no conflict of interests.

Introduction

Chikungunya is a painful affliction characterized by fever, arthralgia, and varying other symptoms 1,2. It is caused by Chikungunya viruses (CHIKV), which are vectored between people primarily by either Aedes aegypti or Ae. albopictus mosquitoes 3, depending on local vector ecology 1 and viral strain 4. Outbreaks of Chikungunya have been highly explosive in a variety of contexts, ranging from tropical islands 5 to temperate mainlands 6. A large portion of cases are thought to be symptomatic 2, making these outbreaks highly conspicuous, readily documentable, and of serious concern to public health.

After its discovery in the 1950s, CHIKV was recognized as the etiological agent in outbreaks that occurred throughout Africa, India, and Southeast Asia over the next several decades 1,7,8. The last ten years, however, have seen an alarming number of outbreaks globally, increased importation to new areas, autochthonous transmission in Europe, and most recently invasion and establishment in the Americas 8,9. The first known autochthonous cases of CHIKV in the Americas were reported on December 5, 2013, and occurred on the island of Saint Martin in the Caribbean 10. Its spread has since continued throughout the Caribbean and into mainland South and North America 9. The sequence of invasion from one country in the Americas to another has received considerable attention from modelers and appears to be somewhat predictable based on flight information, distance between countries, and climatic suitability 11,12,13,14.

There have also been attempts to model the dynamics of the early stages of establishment within a country, yielding estimates of probabilities of autochthonous transmission upon introduction 12,15 and the basic reproductive number R0 13, which is defined as the expected number of secondary infections caused by a single primary infection in a susceptible population. Given the importance of the mosquito vector in transmitting CHIKV, it is to be expected that the potential for autochthonous transmission should depend greatly on local climatic and ecological conditions 16,17 and that this potential should therefore vary greatly in time and space. Efforts to quantify transmission potential to date have relied on empirically derived descriptions of how different components of vectorial capacity depend on weather-related covariates such as temperature and precipitation 12,15, yet there has been very little confirmation that these relationships are predictive of realized patterns of transmission. There has also been scant consideration of susceptible depletion and its feedback on to transmission dynamics via herd immunity, which should be important given the strong protective immunity that Chikungunya infection confers 2,3 and the high seroprevalence observed following outbreaks 5,18,19.

To fill these gaps among models that have been applied to the CHIKV epidemic in the Americas thus far, we adapt the time-series susceptible-infectious-recovered (TSIR) framework 20 for modeling CHIKV transmission dynamics. Originally developed for measles, the TSIR framework has been applied to a variety of infectious diseases since 21,22,23,24,25,26,27 and offers a convenient way to model and estimate susceptible build up and depletion and spatial and temporal variation in transmission. We describe our application of this model to weekly case reports from countries in the Americas during the first year of CHIKV invasion there. In doing so, we establish direct relationships between climatic drivers and transmission, and we propose a platform for future work that will allow for inference of more nuanced links between transmission and putative drivers and for forecasting the continued spread of CHIKV throughout the Americas.

Methods

The goal of our analysis was to understand drivers of spatial and temporal variation in the potential for autochthonous transmission, rather than drivers of pathogen movement and case importation. Consequently, we used a model that accounts for the transmission process locally but that ignores the process of pathogen movement between countries. The question of CHIKV dispersion and importation in the Americas has been addressed previously 11,12,13,14 and is something that could be incorporated into our framework in the future.

Model

Our model pertains to weekly incidence, which is denoted Ii,t for week t in country i. We denote the number of residents of i that are susceptible during week t as Si,t. Given that the duration of infectiousness is expected to be about five days on average 12, the remainder of the population is assumed to have recovered and gained immunity within a week, so Ri,t = Ni – Si,t – Ii,t. In doing so, we assume that the total population size Ni is static and that births and deaths are negligible on the timeframe over which the model is applied. The duration of the incubation period of the virus in humans is expected to be between three and seven days 2, so we assume that cases in week t derive from susceptible people in week t-1. Due to the presence of a vector, the period of time separating successive cases, or the serial interval, is relatively prolonged and variable. To account for this, we introduce a modification to the standard TSIR framework that allows for an arbitrary specification of the serial interval distribution.

To account for this distributed time lag between successive cases, we treated the effective number of infectious people during the time interval in which transmission occurs as

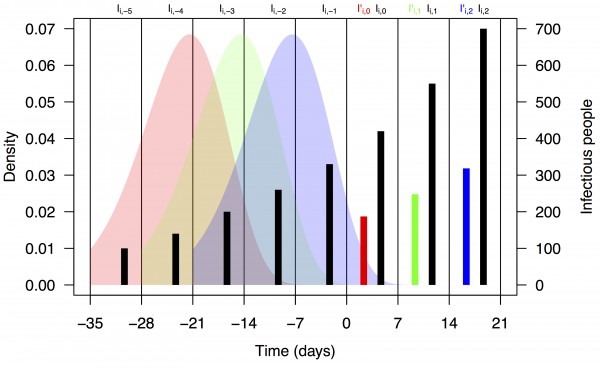

where Ii,t-n are cases acquired locally and ιi,t-n are imported cases. The coefficients that weight contributions of infectious people n weeks ago to infections in the current week are calculated according to

where F is the distribution function of the serial interval and τ is a dummy variable. This formulation assumes that the timing of cases within a week is uniform and that a case on day t arose from a case on day t–τ with probability f(τ), where f is the density function corresponding to F. We chose a functional form and parameters for f and F consistent with a previously published serial interval distribution for CHIKV 13. Assuming a gamma distribution and applying the method of moments to the mean and standard deviation reported in 13, we used values of the shape and rate parameters for the serial interval distribution of 14.69 and 0.64, respectively. Applying these numbers to eqn. (2) using the integrate function in R 28 and normalizing resulted in values of ω1,…,5 = 0.011, 0.187, 0.432, 0.287, and 0.083. A schematic depiction of the calculation of I’i,t based on Ii,t-n and ωn is shown in Fig. 1.

Black bars represent observed weekly case numbers, and red, green, and blue bars in weeks 0-2 represent effective numbers of infectious people in three consecutive weeks. Colored shapes show the serial interval distributions used in the calculation of ωn and then in the calculation of I’i,t in each of weeks 0-2. Weekly case numbers were chosen for pedagogical purposes and do not reflect empirical data.

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of the calculation of effective numbers of infectious people, I’i,t.

Consistent with a frequency-dependent formulation of the TSIR model for directly transmitted pathogens 23, we modeled the dynamics of the infectious class as

where βi,t is a transmission coefficient for country i in week t. Under this formulation, βi,t is related to the basic reproductive number, R0, in country i in week t by

The transmission coefficient βi,t is assumed to implicitly account for a number of factors, including the probabilities of transmission from infectious people to susceptible mosquitoes and from infectious mosquitoes to susceptible people, the ratio of mosquitoes to people, mosquito longevity beyond the pathogen’s incubation period in the mosquito, and the rate at which adult female mosquitoes feed on blood 27. Another assumption of this formulation is that encounters between mosquitoes and people are well mixed, which while potentially problematic for modeling mosquito-borne pathogen transmission 29, can be accounted for phenomenologically by inclusion of the mixing parameter α in [0,1] 30,31. Dynamics of the susceptible and recovered classes follow from eqn. (3), the assumption of recovery within one week, and the assumption of a static population, yielding Si,t = Si,t-1 – Ii,t and Ri,t = Ri,t-1 + Ii,t-1.

Data

The centerpiece of our analysis were weekly numbers of Chikungunya cases on a national scale for countries in the Americas. At the time that we conducted our analysis, there were 1,293,836 cases reported over 61 weeks in 50 countries. Of these, 1,185,728 were suspected cases, each of which corresponded to an individual who sought medical treatment and was diagnosed with Chikungunya based on their presentation of symptoms. An additional 101,651 cases were confirmed by either PCR, serology, or laboratory culture. The remaining 6,457 cases were deemed imported based on travel histories. We obtained data for the first ten weeks from Project Tycho 32, which in turn obtained them from the Agence Régionale de Santé, and for the remaining 51 weeks from the Pan American Health Organization’s website (www.paho.org).

In addition to case numbers, we utilized data on monthly temperature and precipitation averaged at a national scale from 1 km × 1 km gridded data. These data were obtained from WorldClim (www.worldclim.org), and represent interpolated meteorological station data on temperature and precipitation from the 1950-2000 period, processed to create climatological monthly averages that represent “typical” conditions 33. To obtain weekly temperature and precipitation values, we assigned monthly values to weeks that fell entirely within a month and took a weighted average in the event that a week spanned two months. We obtained country-level population estimates from the Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook (www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/). At the onset of CHIKV invasion, we assumed that the entire population of each country was susceptible, with the number of susceptibles in each country decreasing each week thereafter by the numbers of suspected and confirmed cases.

Estimating drivers of transmission

Given data on weekly cases and a generative model for those data, we estimated the mixing parameter α and relationships between local transmission coefficients βi,t and two putative drivers of transmission: temperature and precipitation. To do so, we rearranged terms in eqn. (3) to arrive at the regression equation

where

T’i,t and P’i,t are moving averages of temperature and precipitation in country i in weeks t-5 through t-1, and ε is a normally distributed random variable with mean zero. Regarding the functional form of f(T’i,t,P’i,t), we assumed a quadratic relationship,

because of the general expectation in the literature of a unimodal, and often quadratic, relationship between climatological variables and various aspects of vectorial capacity 12,16,17,47. To select among subsets of this model with the possibility of some coefficients equal to zero, we used the stepAIC function in the MASS package 35 in R 28. This applied both forward and backward selection to yield a model minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion and estimates of best-fit values of its coefficients. Because weeks in which either Ii,t or I’i,t equalled zero were not informative in the regression, we performed this analysis only for country-weeks in which these conditions were not violated. We furthermore excluded weeks for which I’i,t < 1 to preserve a single case as a lower bound for generating autochthonous transmission. We considered Ii,t to include both suspected and confirmed cases and ιi,t to represent imported cases. To examine patterns of variation in transmission predicted by the best-fit model, we computed values of βi,t based on the fitted model for 53 countries in the Americas in each of 52 weeks in a year with a typical temperature and precipitation regime.

Term

Parameter

Estimate

Standard error

t

p

Intercept

a0

-25.66

6.702

-3.829

1.46 × 10-4

T’i,t

a1

2.121

0.5733

3.699

2.41 × 10-4

P’i,t

a2

1.188 × 10-2

4.190 × 10-3

2.836

4.76 × 10-3

T’i,t2

a3

-4.231 × 10-2

1.198 × 10-2

-3.533

4.51 × 10-4

P’i,t2

a4

-2.882 × 10-5

1.116 × 10-5

-2.582

1.01 × 10-2

ln(I’i,t)

α

0.7413

3.285 × 10-2

22.571

< 2 × 10-16

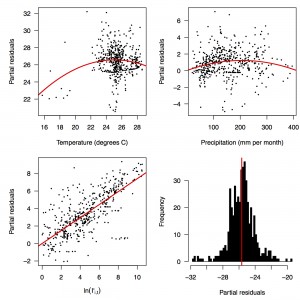

Fig. 2: Partial residual plots of the fitted regression for temperature (top left), precipitation (top right), ln(I’i,t) (bottom left), and the intercept (bottom right).

The line shows a one-to-one relationship for context.

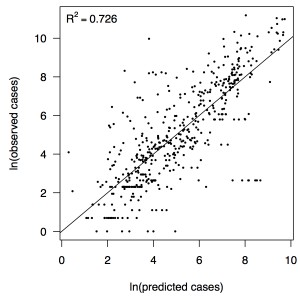

Fig. 3: Relationship between predicted and observed cases in 484 country-weeks on a log-log scale.

Results

Performing a regression of incidence against temperature and precipitation according to eqns. (5)-(7) yielded significant associations between transmission and linear and quadratic terms for temperature and precipitation (F5,478 = 256.9, p < 2.2 × 10-16) (Table 1). There was likewise strong support for a mixing parameter less than one, with a best-fit estimate of α = 0.74 (t = 22.57, p < 2 × 10-16). Although models with fewer terms were fitted and compared, the full model in eqn. (7) had the lowest AIC value and was thus supported as the best model by that criterion. Partial residual plots provided an indication of the extent to which each variable accounted for different portions of overall residual variation (Fig. 2). Overall, the model accounted for 72.6% of variation in incidence among country-weeks, as determined by adjusted R2 (Fig. 3).

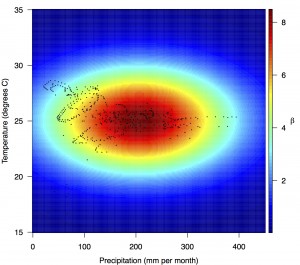

Points show temperature and precipitation values associated with country-weeks with positive incidence that were used in the regression.

Fig. 4: Fitted relationship for f(T’i,t,P’i,t), which models the influence of weekly mean temperature and precipitation on the transmission coefficient βi,t.

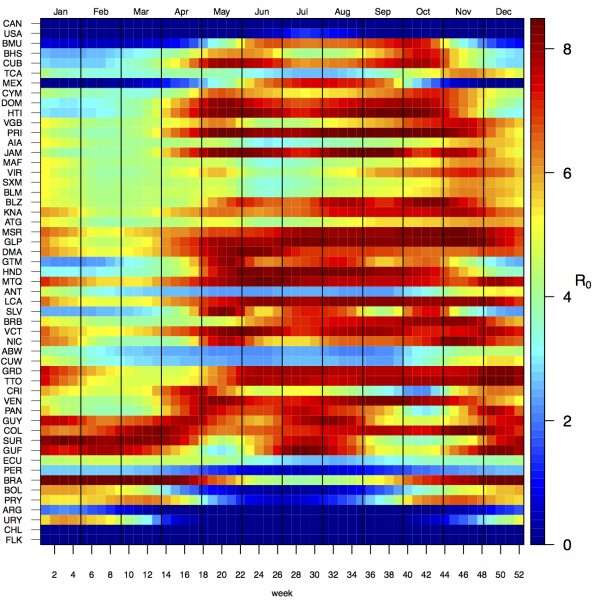

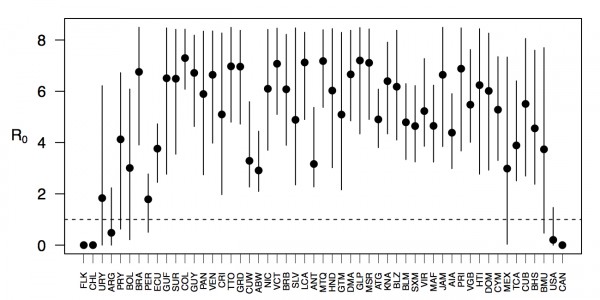

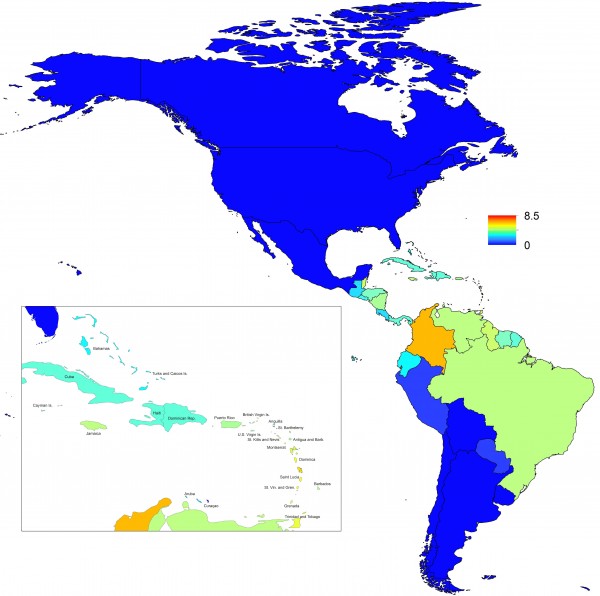

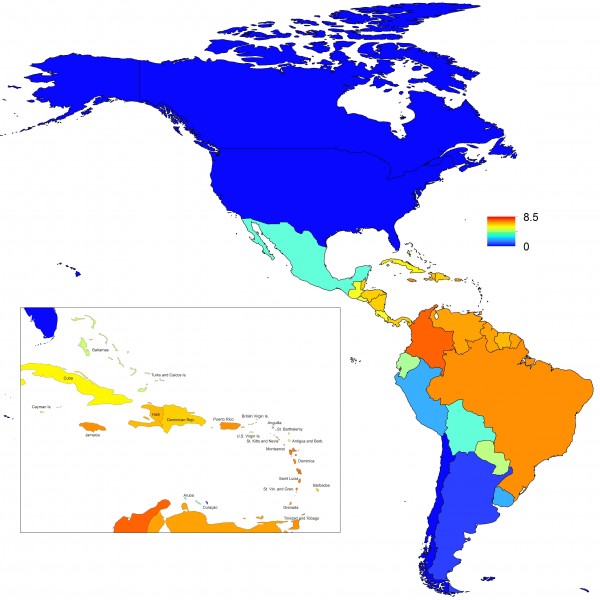

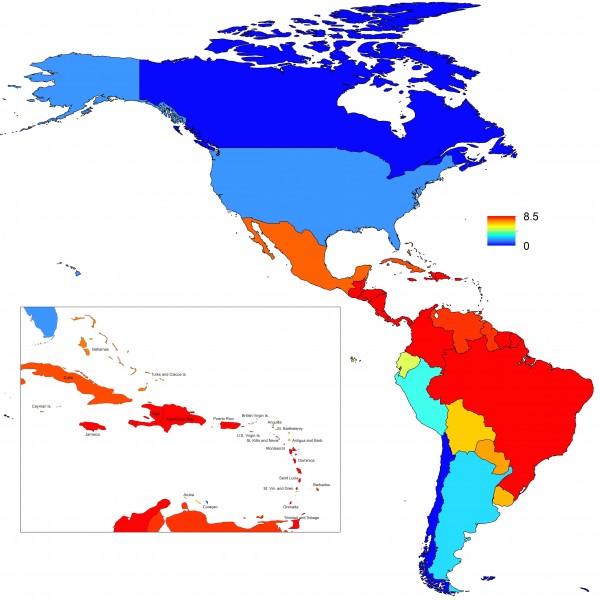

Projections of the fitted model indicated that the transmission coefficient, and R0, should be highest at a temperature of 25 °C and monthly precipitation of 206 mm (Fig. 4). Most country-weeks that experienced autochthonous transmission of CHIKV fell within approximately 3 °C of the temperature optimum but across a large swath of monthly precipitation values (Figs. 2 & 4). Applying the best-fit model to temperature and precipitation data from all 52 weeks in 53 countries showed that the timing and duration of high-transmission seasons are projected to vary substantially across countries (Fig. 5). Such differences mimic clear latitudinal patterns in the seasonality of temperature and, in some areas, precipitation. In general, countries at high and mid latitudes were projected to have the highest potential for Chikungunya transmission from April through November and countries at low latitude from November through April, although there were of course some exceptions to these general patterns (Fig. 5). In addition to geographic variation in seasonality, the best-fit model also projected that mid-latitude countries should generally have higher transmission potential than those at latitudinal extremes (Fig. 6-9). Some outliers included countries with substantial areas of high-altitude terrain, such as Ecuador and Peru.

Countries are sorted by the latitudes of their capital cities.

Fig. 5: Seasonal patterns of projected weekly R0 by country.

Points show mean values across the year and line segments span the ranges of weekly values. Countries are sorted by the latitudes of their capital cities.

Fig. 6: Variation in the range of projected weekly values of R0 by country.

Discussion

The ongoing epidemic of Chikungunya throughout the Americas is nearing 1.3 million cases and is showing no signs of abating. In many ways, the present time is a critical juncture in the pathogen’s invasion and in the public’s response to it. Because CHIKV has been spreading in the Americas for over a year, there are sufficient data to begin analyzing its spread and learning about drivers thereof, as we have demonstrated in the present analysis. At the same time, there are many more millions of people at risk, so improving the capacity to forecast, prepare for, and mitigate outbreaks is paramount. In the present study, we have made several advances towards this goal.

Building on successful application of TSIR models to childhood and other diseases 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, we have proposed this framework as a potentially useful tool for modeling CHIKV transmission. Application of this method to CHIKV is reasonable based on a number of similarities between these pathogens, including the development of strong protective immunity, a reasonably short period of infectiousness, and the potential to rapidly infect (and induce immunity in) large numbers of people. At the same time, application of this method to CHIKV requires some important considerations. First, incorporation of frequency-dependent transmission and dependence on climatic drivers is critical 22,24. Second, the serial interval for vector-borne diseases is necessarily much longer than it is for directly transmitted diseases due to incubation of the pathogen in the vector and the possibility of prolonged transmission over multiple feeding cycles of the vector. By proposing a formulation of the TSIR model similar to an autoregressive moving average time series model, we have provided a new way to accommodate this important feature of vector-borne disease biology without unnecessarily aggregating data temporally and thus potentially compromising information content of the data.

A powerful feature of the TSIR framework is that it reveals variation in transmission and provides a clear and uncomplicated way of statistically associating that variation with putative drivers of transmission. Our analysis of 484 country-weeks of data indicated that there were significant relationships between country-level transmission of CHIKV and typical temperature and precipitation regimes. The concordance of these inferred relationships with previous knowledge is encouraging, because these relationships were apparent in our analysis only because of their demonstrated relationship with variation in transmission and not because of a priori assumptions. The inferred association between temperature and transmission is reasonable due to its height in the 20-30 °C range, although the inferred optimum of 25 °C is lower than some studies would suggest 12,16 but consistent with others 17. The relationship between precipitation and transmission that we inferred is also biologically plausible, as extremely low precipitation would make for insufficient mosquito breeding habitats, and too much could flood eggs from breeding habitats or make people less likely to store water and thereby reduce habitat for the aquatic stages of the Aedes aegypti mosquito that has been implicated in the current outbreak. For both of these relationships, it is worth bearing in mind that values of the covariate climate data that we used reflect national and long-term averages, and values in more localized areas where transmission occurs will vary considerably and exhibit inter-annual variations. Consequently, our estimates of optimal conditions for transmission are not directly comparable to estimates derived from local studies. Nonetheless, the relationships that we inferred are biologically plausible and, in the spirit of forecasting, predictive of variation in transmission.