Abstract

Background

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a lethal, progressive, muscle-wasting disease caused by mutations in the DMD gene. Structural remodelling processes are responsible for muscle atrophy and replacement of myofibers by fibrotic and adipose tissues. Molecular interventions modulating catabolic pathways, such as the ubiquitin-proteasome and the autophagy-lysosome systems, are under development for Duchenne and other muscular dystrophies. The Akt signaling cascade is one of the main pathways involved in protein synthesis and autophagy repression and is known to be up-regulated in dystrophin null mdx mice.

Results

We report that autophagy is triggered by fasting in the tibialis anterior muscle of control mice but not in mdx mice. Mdx mice show persistent Akt activation upon fasting and failure to increase the expression of FoxO3 regulated autophagy and atrophy genes, such as Bnip3 and Atrogin1. We also provide evidence that autophagy is differentially regulated in mdx tibialis anterior and diaphragm muscles.

Conclusions

Our data support the concept that autophagy is impaired in the tibialis anterior muscle of mdx mice and that the regulation of autophagy is muscle type dependent. Differences between muscle groups should be considered during the pre-clinical development of therapeutic strategies addressing muscle metabolism.

Funding Statement

The BIO-NMD project (EU 241665) is acknowledged for funding this work. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.Background

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is the most common neuromuscular disorder. DMD is caused by the complete absence of the dystrophin protein, which leads to extensive muscle degeneration and regeneration followed by substitution of muscle with fibrotic and adipose tissues 1,2. No cure is yet available, but several therapeutic approaches aiming at reversal of the ongoing degeneration have been investigated in preclinical and clinical settings with disappointing results 3,4,5. Currently, drugs intended to induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy via Akt-mediated protein synthesis are in preclinical (e.g. valproic acid) or clinical (e.g. IGF-1) development 6,7,8 (see also http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01207908). IGF-1 is able to trigger Akt phosphorylation via class I PI3K 9,10 , which in turn induces a series of biochemical changes leading to protein synthesis via the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway 11,12,13 . At the same time, Akt is able to repress catabolic pathways, such as macroautophagy (hereafter referred as autophagy) and ubiquitin-proteasome, leading to muscle atrophy 14,15 . This repression can occur in a transcriptional and non-transcriptional fashion. Indeed, it is known that mTOR inhibition by rapamycin induces autophagy without affecting gene expression, while Akt can repress the transcription factor FoxO3. This transcription factor is involved in the transcriptional activation of the atrophy genes Atrogin1 and MuRF1 and the autophagy gene Bnip316,17 . Therefore, the autophagy-lysosome system might also be a potential target for therapeutic intervention for muscular dystrophies.

The autophagic pathway is responsible for the removal of unfolded/toxic proteins as well as dysfunctional/abnormal organelles. It is constantly active in skeletal muscle and is involved in several conditions such as denervation, cachexia and fasting 18. We recently reported that autophagy is impaired in collagen VI-related myopathies and that induction of autophagy can rescue myofibers defects of collagen VI deficient mice 19,20. The Akt/mTOR axis is one of the key pathways regulating autophagy. Previous studies showed that Akt signaling is affected in dystrophin null mdx mice 21. In fact, Akt signaling is strongly enhanced in 4-week-old mdx mice, i.e. the period when extensive muscle regeneration is occurring 22 . This enhancement of Akt signaling decreases over time with a slight up-regulation in 3-month-old mice 23,24 and hardly any up-regulation in older mice 25 . Recently it was reported that both activation of autophagy by an AMPK agonist and inhibition of autophagy by Akt activation via valproic acid could ameliorate the dystrophic phenotype of mdx mice 6,26 . Furthermore, it was shown that autophagy is impaired in both glycolytic and oxidative muscles of mdx mice 27 . In the present study, we analyzed the Akt/mTOR pathway under basal conditions and after fasting in mdx and wild-type mice. We found a persistent activation of the Akt/mTOR pathway after fasting in the mdx mice tibialis anterior but not in the diaphragm. Taken together, these data show that abnormal Akt signaling differentially impacts the regulation of the autophagy machinery in diverse dystrophin deficient muscles.

Methods

Ethical approval

All procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare Commission of the Leiden University Medical Center (work protocol 11071). The institution is authorized by the government to judge the proposals according to the law. All experiments were performed in accordance with the regulations for animal experimentation.

Mice

C57BL/10ScSn-mdx/J (mdx) and control C57BL/10 mice were fed ad libitum with chow until 16 weeks of age. At this age, mice were divided into the fed or fasting groups (4-5 mice per group). Fasting started at 9 am in the morning and lasted for 24 hours. Mice from both groups were then sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Tibialis anterior and diaphragm muscles were harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen before further processing.

q-RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using Tripure reagent as described previously 28 . The RNA concentration was measured on a Nanodrop (Nanodrop Technologies, USA) and integrity was checked with a total RNA nano chip assay on the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, the Netherlands). cDNA synthesis was performed using random hexamer primers and gene expression levels were determined by Sybr Green based Real Time qPCR on the Roche Lightcycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics Ltd, UK). All primer pairs used spanned at least one splice junction to avoid contamination with genomic DNA amplification. Relative expression was determined using Gapdh as reference gene, while primer efficiencies were determined with LinReg PCR version 11.3.

Western Blot

Frozen muscles were homogenized by grinding in liquid nitrogen, lysed and immunoblotted as previously described 19 . When needed, membranes were stripped using a stripping buffer (25 mM glycine, 1% SDS, pH 2.0) and reprobed. The following antibodies from Cell Signalling Technologies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt; rabbit monoclonal (clone 193H12) anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473); rabbit polyclonal anti-4EBP1; rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho- 4EBP1 (Ser65). The rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3B was from Tema Ricerca and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH was from Millipore. Western blots were performed for a minimum of three independent experiments. Densitometric quantification was carried out using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analysis

To test whether changes in gene expression levels were significant between fed and fasted mice, we used one-way ANOVA followed by Post-hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Autophagy is impaired in mdx mice

To investigate autophagy regulation in mdx mice, we chose the tibialis anterior and diaphragm muscles as they are examples of glycolytic and oxidative muscles, respectively 19,27,41 . We investigated 16-weeks-old mice, since it is known that mdx mice undergo extensive muscle regeneration between 6 and 12 weeks of age, which could confound the results. Notably, this muscle regeneration does not occur in Duchenne patients 22 .

We first assessed Akt phosphorylation in wild-type and mdx muscle from mice that were fed ad libitum and did not observe significant differences between the two groups (Figure 1). In agreement with this, no differences were found in the phosphorylation state of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1), which dissociates from the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) and activates mRNA translation when phosphorylated. Furthermore, no differences were observed in the lipidated form of the microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3 (LC3-II), which is produced during the autophagosome formation 29,30 . Fasting for 24 hr induced autophagy in wild-type and mdx mice diaphragm, leading to decreased phosphorylation of Akt and 4EBP1 and increased levels of LC3-II. Conversely, 24 hr fasting induced autophagy in tibialis anterior muscle of wild-type but not of mdx mice. Indeed, only the tibialis anterior of wild-type mice showed autophagy induction, while in mdx mice Akt and 4EBP1 remained phosphorylated. The LC3-II form was also less abundant in the tibialis anterior of mdx mice, confirming that this muscle was resistant to autophagy induction (Figure 1).

Western blot of phosphorylated and total Akt, phosphorylated and total 4EBP1, and LC3 lipidation in diaphragm and tibialis anterior muscles of wild-type and mdx mice at basal level and after 24 hour fasting (n=4-5). GAPDH was used as loading control. Densitometric quantification of phospho-Akt, phospho-4EBP1 and ratio between LC3-II vs LC3-I form are also shown (*P<0.05). Expression levels are represented as arbitrary units. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Fig. 1: Autophagy is impaired in mdx mice

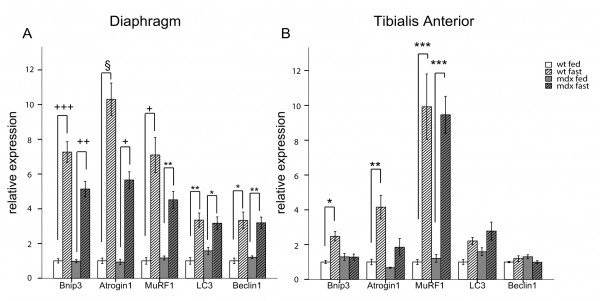

Autophagy impairment is mediated by FoxO3 transcription factor

Akt is known to be one of the most potent modulators of autophagy and inhibition of the IGF-1/Akt pathway during fasting stimulates autophagy mainly via an mTOR independent mechanism 18 . Therefore, we studied the expression of some regulatory genes involved in autophagy induction, such as Beclin1. Furthermore, we focused in particular on FoxO3-regulated genes, such as LC3 and Bnip3. The latter is the main gene involved in fasting-induced autophagosome formation in muscle 16 and a key regulator of the autophagic removal of mitochondria 31,32 . In the diaphragm of wt and mdx mice, fasting for 24 hours induced potent up-regulation of the autophagy activation genes Bnip3 and Beclin1 as well as the ubiquitin-ligase genes Atrogin1 and MuRF1 (Figure 2A). However, in the glycolytic tibialis anterior muscle, fasting induced Bnip3 expression in wild-type mice only, while no difference was observed between fed and fasted mdx mice. Similar results were obtained for Atrogin1, an atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase also regulated by FoxO3.The levels of MuRF1, another atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase regulated by NF-κB, were increased in the muscles of fasted mdx and wild-type mice compared to fed mice. No significant changes were observed in the expression of LC3 and Beclin1 (Figure 2B).

q-RT-PCR analysis showing the quantification of the genes involved in the autophagy regulation. Bnip3, Atrogin1, MuRF1, LC3 and Beclin1 are shown for diaphragm (A) and tibialis anterior (B) muscles (n=4-5). White bars represent fed wild-type mice, hatched white bars represent fasted wt mice, grey bars represent fed mdx mice and hatched grey bars represent fasted mdx mice. (* P<10-2, ** P<10-3, *** P<10-4, +P<10-5, ++ P<10-6, +++ P<10-7, § P<10-8). Bars represent the mean expression relative to the wt fed mice group which is set to 1. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Fig. 2: Autophagy impairment is mediated by FoxO3 transcription factor.

Discussion

DMD is the most severe form of muscular dystrophy and also the most common neuromuscular disorder. Transcriptomic and proteomic studies have reported major metabolic and physiological changes in DMD patients and animal models, including mitochondrial defects 22,33,34,35,36 . Structural remodelling processes, such as extensive muscle regeneration, can compensate for dystrophin absence during the early stages of the disease in which young patients are still able to walk. To identify potential therapeutic targets for DMD, several studies focused on pathways involved in muscle hypertrophy, such as myostatin inhibition or IGF-1/Akt activation 6,37 . Akt stimulates protein synthesis and hypertrophy by inhibiting the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), which inhibits mTOR 38 . At the same time, Akt inhibits autophagy by phosphorylating the FoxO3 transcription factor 16,39 . Several reports have shown that Akt is more active in mdx compared to wild-type mice, although differences in Akt signaling were reported to be age- and muscle-dependent. Indeed, it is known that mdx mice at about 6-12 weeks of age show extensive muscle regeneration when compared to older mdx mice 22 and that Akt signaling decreases over time in mdx mice 25 .

We recently reported defective autophagy regulation in another animal model of muscular dystrophy, the collagen VI null (Col6a1–/–) mouse. In Col6a1–/– mice, autophagy is strongly impaired in the tibialis anterior muscle, while in the diaphragm the autophagy machinery is less compromised 19 . Here we show comparable results in the mdx mouse, where the autophagy pathway is normally regulated in the diaphragm and impaired in a highly glycolytic muscle such as the tibialis anterior.

Autophagy impairment in mdx tibialis anterior muscle could be due to persistent Akt activation; this however remains to be tested by e.g. knocking down Akt during the period of food deprivation. Differential physical activity levels between mdx and wt mice could also account for this difference, since it has been shown that exercise can influence autophagy 42 . However mice involved in our experiment were not exercised, even though it is known that mdx mice move less compared to wt mice. Future experiments will also need to determine what causes the different response to fasting observed in mdx muscles. We hypothesize that muscle condition could be a factor, since the diaphragm is the most severely affected muscle in mdx mice while the tibialis anterior is mildly affected; myofiber composition could also participate to the difference observed between the two muscles as tibialis anterior and diaphragm have been considered in the past as examples of glycolytic and oxidative muscles 41 .

These findings are partially in line with recently published data demonstrating that autophagy is equally impaired in both tibialis anterior and diaphragm muscles 27 . A possible reason for the difference between our experiment and the one by De Palma and colleagues is the fasting time which was 24 hours in our case compared to 15 hours in the article by De Palma et al. It is possible that 15 hours are not sufficient to trigger autophagy in mdx mice diaphragm. Our current data clearly shows a differential autophagy response in distinct muscle types and we think that this should be taken into account when designing therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway. Autophagy activation in the diaphragm of mdx mice was shown to be beneficial either via an AMPK agonist 26 that rescued the PTP function, or by rapamycin mediated inhibition of mTOR that decreased the number of necrotic and regenerating fibers 40 . On the contrary, the same treatment did not lead to mTOR inhibition in the tibialis muscle, underlining the differences between glycolytic and oxidative muscles. It is known that Akt overexpression in the glycolytic gastrocnemius of mdx mice is able to protect from isometric force drop after eccentric contractions in vivo8 . The positive role of Akt signaling in glycolytic muscles is also confirmed in the plantaris muscle, where Akt signaling is induced, but represents a limiting factor to muscle remodeling following mechanical overloading 23 . However, it has also been reported that IGF-1 up-regulation in the oxidative mdx diaphragm can cause hypertrophy and hyperplasia reducing fibrosis 24 .

Our data demonstrate that autophagy is differentially regulated in tibialis anterior and diaphragm muscles of mdx mice. Given the difference in fiber type composition between human and mouse (humans do not have the glycolytic type IIB myosin heavy chain 43 ), the results obtained in mice diaphragm better represents the fiber type composition in human skeletal muscle. This suggests that both AMPK agonists and IGF-1 could be good candidates to test in patients given the positive results obtained in mdx mice, even though the two approaches aim at diametrically opposite biochemical results. Before clinical experimentation, however, therapeutic interventions aiming to interfere with the Akt autophagy pathway should be carefully evaluated considering the differences between muscle groups and preferably show that both muscle types respond positively to the treatment.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that autophagy was not induced after fasting in the tibialis anterior muscle of dystrophin null mice. Autophagy was potently induced in the diaphragm muscle of mdx as well as wt mice. The difference between the two types of skeletal muscle underlines the fact that a specific treatment to improve muscle condition could have a different effect in different types of muscle.

Corrisponding authors

Annemieke Aartsma-Rus

Human Genetics Department

Leiden University Medical Center

Paolo Bonaldo

Department of Molecular Medicine

University of Padova

Keywords

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy; Autophagy; Macroautophagy; mdx mouse.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgements

Peter ‘t Hoen is acknowledged for critical suggestions and discussion over the results. Willeke van Roon-Mom is acknowledged for revising the English throughout the text.

* Pietro Spitali and Paolo Grumati contributed equally to this work

References

- Norwood FL, Harling C, Chinnery PF, Eagle M, Bushby K, Straub V. Prevalence of genetic muscle disease in Northern England: in-depth analysis of a muscle clinic population. Brain. 2009 Nov;132(Pt 11):3175-86. PubMed PMID:19767415.

- Bushby K, Finkel R, Birnkrant DJ, Case LE, Clemens PR, Cripe L, Kaul A, Kinnett K, McDonald C, Pandya S, Poysky J, Shapiro F, Tomezsko J, Constantin C. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. Lancet Neurol. 2010 Jan;9(1):77-93. PubMed PMID:19945913.

- Mok E, Letellier G, Cuisset JM, Denjean A, Gottrand F, Alberti C, Hankard R. Lack of functional benefit with glutamine versus placebo in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a randomized crossover trial. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5448. PubMed PMID:19421321.

- Escolar DM, Zimmerman A, Bertorini T, Clemens PR, Connolly AM, Mesa L, Gorni K, Kornberg A, Kolski H, Kuntz N, Nevo Y, Tesi-Rocha C, Nagaraju K, Rayavarapu S, Hache LP, Mayhew JE, Florence J, Hu F, Arrieta A, Henricson E, Leshner RT, Mah JK. Pentoxifylline as a rescue treatment for DMD: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Neurology. 2012 Mar 20;78(12):904-13. PubMed PMID:22402864.

- Buyse GM, Goemans N, van den Hauwe M, Thijs D, de Groot IJ, Schara U, Ceulemans B, Meier T, Mertens L. Idebenone as a novel, therapeutic approach for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: results from a 12 month, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011 Jun;21(6):396-405. PubMed PMID:21435876.

- Gurpur PB, Liu J, Burkin DJ, Kaufman SJ. Valproic acid activates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in muscle and ameliorates pathology in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Pathol. 2009 Mar;174(3):999-1008. PubMed PMID:19179609.

- Yang SY, Hoy M, Fuller B, Sales KM, Seifalian AM, Winslet MC. Pretreatment with insulin-like growth factor I protects skeletal muscle cells against oxidative damage via PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 MAPK pathways. Lab Invest. 2010 Mar;90(3):391-401. PubMed PMID:20084055.

- Blaauw B, Mammucari C, Toniolo L, Agatea L, Abraham R, Sandri M, Reggiani C, Schiaffino S. Akt activation prevents the force drop induced by eccentric contractions in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 Dec 1;17(23):3686-96. PubMed PMID:18753145.

- Dogra C, Changotra H, Wergedal JE, Kumar A. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathways in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle in response to mechanical stretch. J Cell Physiol. 2006 Sep;208(3):575-85. PubMed PMID:16741926.

- Rommel C, Bodine SC, Clarke BA, Rossman R, Nunez L, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Mediation of IGF-1-induced skeletal myotube hypertrophy by PI(3)K/Akt/mTOR and PI(3)K/Akt/GSK3 pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2001 Nov;3(11):1009-13. PubMed PMID:11715022.

- Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonzalez M, Kline WO, Stover GL, Bauerlein R, Zlotchenko E, Scrimgeour A, Lawrence JC, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001 Nov;3(11):1014-9. PubMed PMID:11715023.

- Lai KM, Gonzalez M, Poueymirou WT, Kline WO, Na E, Zlotchenko E, Stitt TN, Economides AN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Conditional activation of akt in adult skeletal muscle induces rapid hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Nov;24(21):9295-304. PubMed PMID:15485899.

- Pallafacchina G, Calabria E, Serrano AL, Kalhovde JM, Schiaffino S. A protein kinase B-dependent and rapamycin-sensitive pathway controls skeletal muscle growth but not fiber type specification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Jul 9;99(14):9213-8. PubMed PMID:12084817.

- Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, Skurk C, Calabria E, Picard A, Walsh K, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004 Apr 30;117(3):399-412. PubMed PMID:15109499.

- Stitt TN, Drujan D, Clarke BA, Panaro F, Timofeyva Y, Kline WO, Gonzalez M, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2004 May 7;14(3):395-403. PubMed PMID:15125842.

- Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, Masiero E, Rudolf R, Del Piccolo P, Burden SJ, Di Lisi R, Sandri C, Zhao J, Goldberg AL, Schiaffino S, Sandri M. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007 Dec;6(6):458-71. PubMed PMID:18054315.

- Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, Cao P, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007 Dec;6(6):472-83. PubMed PMID:18054316.

- Sandri M. Autophagy in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 2010 Apr 2;584(7):1411-6. PubMed PMID:20132819.

- Grumati P, Coletto L, Sabatelli P, Cescon M, Angelin A, Bertaggia E, Blaauw B, Urciuolo A, Tiepolo T, Merlini L, Maraldi NM, Bernardi P, Sandri M, Bonaldo P. Autophagy is defective in collagen VI muscular dystrophies, and its reactivation rescues myofiber degeneration. Nat Med. 2010 Nov;16(11):1313-20. PubMed PMID:21037586.

- Grumati P, Coletto L, Sandri M, Bonaldo P. Autophagy induction rescues muscular dystrophy. Autophagy. 2011 Apr;7(4):426-8. PubMed PMID:21543891.

- Xiong Y, Zhou Y, Jarrett HW. Dystrophin glycoprotein complex-associated Gbetagamma subunits activate phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt signaling in skeletal muscle in a laminin-dependent manner. J Cell Physiol. 2009 May;219(2):402-14. PubMed PMID:19117013.

- Turk R, Sterrenburg E, de Meijer EJ, van Ommen GJ, den Dunnen JT, 't Hoen PA. Muscle regeneration in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice studied by gene expression profiling. BMC Genomics. 2005 Jul 13;6:98. PubMed PMID:16011810.

- Joanne P, Hourdé C, Ochala J, Caudéran Y, Medja F, Vignaud A, Mouisel E, Hadj-Said W, Arandel L, Garcia L, Goyenvalle A, Mounier R, Zibroba D, Sakamato K, Butler-Browne G, Agbulut O, Ferry A. Impaired adaptive response to mechanical overloading in dystrophic skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35346. PubMed PMID:22511986.

- Barton ER, Morris L, Musaro A, Rosenthal N, Sweeney HL. Muscle-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor I counters muscle decline in mdx mice. J Cell Biol. 2002 Apr 1;157(1):137-48. PubMed PMID:11927606.

- Mouisel E, Vignaud A, Hourdé C, Butler-Browne G, Ferry A. Muscle weakness and atrophy are associated with decreased regenerative capacity and changes in mTOR signaling in skeletal muscles of venerable (18-24-month-old) dystrophic mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2010 Jun;41(6):809-18. PubMed PMID:20151467.

- Pauly M, Daussin F, Burelle Y, Li T, Godin R, Fauconnier J, Koechlin-Ramonatxo C, Hugon G, Lacampagne A, Coisy-Quivy M, Liang F, Hussain S, Matecki S, Petrof BJ. AMPK activation stimulates autophagy and ameliorates muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse diaphragm. Am J Pathol. 2012 Aug;181(2):583-92. PubMed PMID:22683340.

- De Palma C, Morisi F, Cheli S, Pambianco S, Cappello V, Vezzoli M, Rovere-Querini P, Moggio M, Ripolone M, Francolini M, Sandri M, Clementi E. Autophagy as a new therapeutic target in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Death Dis. 2012 Nov 15;3:e418. PubMed PMID:23152054.

- Spitali P, Heemskerk H, Vossen RH, Ferlini A, den Dunnen JT, 't Hoen PA, Aartsma-Rus A. Accurate quantification of dystrophin mRNA and exon skipping levels in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Lab Invest. 2010 Sep;90(9):1396-402. PubMed PMID:20458276.

- Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008 Jan 11;132(1):27-42. PubMed PMID:18191218.

- Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Sep;8(9):741-52. PubMed PMID:17717517.

- Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Logue SE, Sayen MR, Jinno M, Kirshenbaum LA, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007 Jan;14(1):146-57. PubMed PMID:16645637.

- Sandoval H, Thiagarajan P, Dasgupta SK, Schumacher A, Prchal JT, Chen M, Wang J. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature. 2008 Jul 10;454(7201):232-5. PubMed PMID:18454133.

- Kuznetsov AV, Winkler K, Wiedemann FR, von Bossanyi P, Dietzmann K, Kunz WS. Impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of the dystrophin-deficient mdx mouse. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998 Jun;183(1-2):87-96. PubMed PMID:9655182.

- Allen DG, Whitehead NP. Duchenne muscular dystrophy--what causes the increased membrane permeability in skeletal muscle? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011 Mar;43(3):290-4. PubMed PMID:21084059.

- Lawler JM. Exacerbation of pathology by oxidative stress in respiratory and locomotor muscles with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Physiol. 2011 May 1;589(Pt 9):2161-70. PubMed PMID:21486793.

- Petrof BJ. Molecular pathophysiology of myofiber injury in deficiencies of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Nov;81(11 Suppl):S162-74. PubMed PMID:12409821.

- Kemaladewi DU, de Gorter DJ, Aartsma-Rus A, van Ommen GJ, ten Dijke P, 't Hoen PA, Hoogaars WM. Cell-type specific regulation of myostatin signaling. FASEB J. 2012 Apr;26(4):1462-72. PubMed PMID:22202673.

- Hahn-Windgassen A, Nogueira V, Chen CC, Skeen JE, Sonenberg N, Hay N. Akt activates the mammalian target of rapamycin by regulating cellular ATP level and AMPK activity. J Biol Chem. 2005 Sep 16;280(37):32081-9. PubMed PMID:16027121.

- Birkenkamp KU, Coffer PJ. Regulation of cell survival and proliferation by the FOXO (Forkhead box, class O) subfamily of Forkhead transcription factors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003 Feb;31(Pt 1):292-7. PubMed PMID:12546704.

- Eghtesad S, Jhunjhunwala S, Little SR, Clemens PR. Rapamycin ameliorates dystrophic phenotype in mdx mouse skeletal muscle. Mol Med. 2011 Sep-Oct;17(9-10):917-24. PubMed PMID:21607286.

- Augusto V, Padovani CR, Campos GER: Skeletal muscle fiber types in C57BL6J mice. Braz J Morphol Sci 2004, 21: 89-94.

Reference Link - He C, Bassik MC, Moresi V, Sun K, Wei Y, Zou Z, An Z, Loh J, Fisher J, Sun Q, Korsmeyer S, Packer M, May HI, Hill JA, Virgin HW, Gilpin C, Xiao G, Bassel-Duby R, Scherer PE, Levine B. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2012 Jan 18;481(7382):511-5. PubMed PMID:22258505.

- Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol Rev. 2011 Oct;91(4):1447-531. PubMed PMID:22013216.